In the years since the publication of comprehensive critical care (DH, 2000), CCOTs have developed across most acute hospitals in England. However, this has not happened in a uniform manner. Services still vary in the hours that they are available, the amount of dedicated medical input, the number and position of nursing staff involved, and the overall approach of the team (Deacon, 2009).

Multiprofessional CCOTs by their very nature have an advantage when communicating with different disciplines across hospital environments. The majority of CCOTs that have shown measurable benefits have been multiprofessional (Cutler and Robson, 2006). There is variety in the amount of medical input into CCOTs and most services are nurse led, Gao et al., (2007) reported that 71.1% of services had no medical input at all.

In recent clinical guidance relating to the acutely ill hospital patient, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE, 2007) reviewed available evidence relating to track-and-trigger systems being used internationally. While the evidence was able to suggest some pros and cons of different systems, it was felt there wasn’t sufficient evidence to recommend one particular system over another. One thing that is clear is the recommendation that all adult patients in acute hospital settings should be monitored with a track-and-trigger system, but the choice of which particular system to use should be decided at a local level.

The MEWS is an example of an aggregate scoring track-and-trigger system and is used widely in the UK (Figure 11.1). A MEWS score of 2 in any single category indicates the need for close and frequent observation of the patient. A MEWS score of 4 and/or an increase of 2 or more indicates that the patient is potentially unwell and means that urgent medical attention is required. While it has been established that physiological abnormality is associated with adverse outcome, within a recent Cochrane review it was stated that the use of early warning scores or outreach calling criteria in the practice setting needs to be evaluated. This would provide an understanding of the factors associated with poor documentation of EWS charts and the reluctance of ward staff to use the calling criteria (McGaughey, 2009).

Assessing the Emergency Cardiac Patient

For all patients who present with a possible cardiac emergency, the initial nursing assessment should be focused, specific and efficiently undertaken. It follows the same approach that can be used for the assessment of all groups of patients.

A – Airway

- Ensure the patient’s airway is patent, i.e. is the patient talking to you?

- Administer oxygen therapy as indicated via the appropriate oxygen delivery device at 15 l high flow oxygen.

B – Breathing

- Look at the patient – are they pale or are there any signs of cyanosis?

- What is their respiratory rate?

- What is their respiratory effort like? Are they using any accessory muscles?

- Are they speaking full sentences or do they have to keep stopping to take a breath?

C – Circulation

- Pulses – are they all present? Are they equal on both sides?

- What is the rate? What is the volume like? Are there any particular characteristics? i.e. regular/irregular?

- Blood pressure – what is it? Is it equal on both sides?

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) – three-lead monitor should be attached and 12-lead ECG undertaken as soon as possible, dependent on the patient’s condition, to assess for abnormalities.

- Intravenous (IV) access should be gained and bloods taken – appropriate for their presenting problem and local guidelines.

- IV analgesia should also be given at this point if indicated.

- Care should be taken with opioid analgesia – see specific sections.

D – Disability

- How is the patient responding?

- Use the AVPU scale to assess the patient – are they alert (A), responsive to voice (V), responsive to pain (P) or are they unresponsive (U)?

- Pupils – are they equal and reactive to light?

E – Exposure

- Prepare the patient for full examination while keeping them warm and preserving their dignity.

Additional Information

While undertaking the above assessment, there is information that is needed to be gained from the patient about themselves and their presenting complaint. This further information can be remembered using the mnemonic SAMPLE.

S – Signs and Symptoms

- What were the signs and symptoms that led to concern for the patient/practitioner?

- Signs – things you can see or hear.

- Symptoms – things the patient reports.

A – Allergies

- Are they allergic to any medications?

- Are they allergic to any other product you may use on them, i.e. Elastoplast, latex?

M – Medication

- What medications do they normally take?

- What dose do they normally take?

- Have they taken it today as normal?

- Do any of their medications have cardiac side effects?

- Are they on any new medications that maybe reacting with others?

P – Past medical history

- Is there any relevant history?

- Are they known to have any cardiac problems?

- Have they got any respiratory problems?

L – Last eaten

- The time of their last drink or food – can be relevant if they require any sedation or anaesthetic.

E – Events

- Events of this episode.

- What happened?

- When did it happen?

- What were they doing when it happened?

- Were there any witnesses to the event?

- Have they had similar episodes before?

- If so, what happened then?

- What was the outcome/diagnosis?

By using this systematic assessment, patients with possible cardiac emergencies can be quickly and thoroughly assessed. The level of intervention will vary depending on the nurse’s skill, e.g. does the nurse have the ability to insert an IV cannula, and are they a nurse prescriber.

Reassurance also plays a large part in the management of these patients. Patients with cardiac emergencies tend to be frightened and this in turn puts a greater strain on their cardiac system. Therefore they need reassurance, which also includes the need to be treated in a calm environment by a team of staff who have a calm demeanour.

Acute Heart Failure

Heart failure is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the Western world and the incidence of heart failure is increasing because of the ageing population.

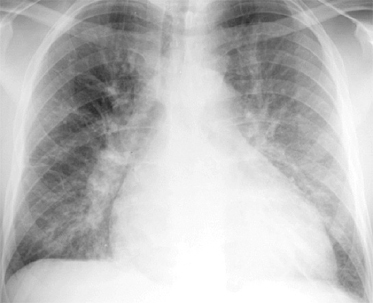

Heart failure is an abnormality of cardiac structure or function that reduces the heart’s ability to eject blood (systolic dysfunction) or fill with blood (diastolic dysfunction). Acute heart failure is a sudden reduction in cardiac performance, resulting in acute pulmonary oedema. Clinical and radiographic assessment of these patients provides a guide to the severity and prognosis (Millane et al., 2000). There is an accumulation of fluid within the alveolar spaces which leads to the lungs becoming stiff, and subsequently gaseous exchange is impaired leading to worsening hypoxaemia and hypercapnia, which is life threatening. The major effects of heart failure are reduced organ perfusion, arrhythmias and vasoconstriction, which in turn cause their own problems (Souhami and Moxham, 2002).

Causes

Pulmonary oedema is an abnormal amount of interstitial fluid in the interstitial spaces and alveoli. The oedema may arise from increased pulmonary capillary permeability (pulmonary origin) or from an increase in pulmonary capillary pressure (cardiac origin) and heart failure. As the heart becomes less effective, more blood remains in the ventricles at the end of each cardiac cycle and therefore the end-diastolic volume (pre-load) increases. If the left ventricle is the first to fail, it becomes unable to pump out all of the blood it receives so it backs up in the lungs, causing increased pulmonary pressure. Whereas if the right ventricle fails first, the blood backs up systemically, i.e. pedal oedema (Tortora and Derrickson, 2008).

Heart failure may occur due to a combination of factors such as:

- pneumonia (common in elderly patients)

- hypoxia

- cardiac ischaemia

- sepsis

- renal failure.

The main differential diagnosis that can be mistakenly diagnosed as heart failure is acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as it is often difficult to distinguish between the two. Therefore care is required when taking the patient’s history, including past medical history. It is imperative that the diagnosis of heart failure is accompanied by an urgent attempt to establish its cause, as timely intervention may greatly improve the prognosis in selected cases. Severe acute heart failure is a medical emergency, and effective management requires an assessment of the underlying cause, improvement of the haemodynamic status, relief of pulmonary congestion and improved tissue oxygenation. In patients with acute heart failure, an underlying infection is common (Sprigings and Chambers, 2001).

Contributing Factors

- Genetic family history of heart failure.

- Ischaemic heart disease/myocardial infarction (coronary artery disease) leading to reduced cardiac function.

- Thyrotoxicosis (hyperthyroidism).

- Arrhythmias.

- Hypertension – long-term increases the afterload of the heart.

- Cardiac fibrosis.

- Coarctation of the aorta.

- Aortic stenosis/regurgitation.

- Mitral regurgitation.

- Pulmonary stenosis/pulmonary hypertension/pulmonary embolism.

- Mitral valve disease.

Presentation

These patients are often acutely unwell and extremely frightened and agitated, can be mildly aggressive and do not like oxygen masks as they feel they restrict their breathing even more.

Their presentation includes the following.

- Acute shortness of breath which is usually the first symptom and may be the reason the patient presents themselves to a practitioner.

- Often the patient may collapse.

- Pallor and/or cyanosis which is often a late sign.

- Unable to speak full sentences.

- Agitation.

- Diaphoresis.

- Raised jugular venous pressure (JVP).

- Low volume pulse.

- Ankle/pedal oedema.

- Muffled heart sounds on auscultation.

- Feeble pulse.

- Often hypertension.

Other associated features which may reflect underlying cause include the following.

- Chest pain may be present.

- Palpitations may also be present.

- Dyspnoea on exertion, which is an early sign and may be present for some weeks before the patient seeks advice.

- Orthopnoea may also have been present for some weeks before.

Priorities of Assessment

For this group of patients the priorities initially are as follows.

- Assess the patient following the ABCDE approach.

- Administer oxygen therapy as indicated via the appropriate oxygen delivery device; sit the patient in an upright position.

- Establish oxygen saturation monitoring using a pulse oximeter. Be aware that SpO2 may not give accurate reading due to peripheral shutdown.

- Ensure patient has a wide-bore IV cannula in place (e.g. 14 gauge).

- Establish continuous ECG monitoring; and undertake a 12-lead ECG.

- Closely monitor the patient’s vital signs with frequent reassessments – deterioration may be rapid; include blood pressure, temperature, pulse and respiratory rate. Close observation and frequent reassessment are required in the early hours of treatment.

- Prepare for transfer to high-dependency care area. Patients with acute severe heart failure, or refractory symptoms, should be monitored in a high-dependency unit.

- Urinary catheterisation facilitates accurate assessment of fluid balance, maintenance of >30 ml/h.

- Arterial blood gases monitoring; this provide valuable information regarding oxygenation and acid-base balance.

- Reassurance is vital with this group of patients as they will be extremely frightened and distressed.

Monitor vital signs with frequent reassessment (blood pressure, pulse, respiration rate, ECG and urine output). An arterial line can be inserted for ease of obtaining arterial blood gases and also to monitor BP more accurately. In severe cases the patient may require continuous positive airway pressure ventilation (CPAP) to assist their breathing. Remember a “normal” blood pressure can be maintained by vasoconstriction and does not indicate adequate organ perfusion (Sprigings and Chambers, 2001).

The aims of treatment are to:

- reduce the symptoms of dyspnoea (most important)

- reduce cardiac filling pressures

- reduce excess intravascular volume

- reduce vascular resistance

- increase cardiac output.

Treatment Priorities

- Glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) infusion commencing at 0.6 mg/h dependent on the patient’s blood pressure, i.e. systolic above 100 mm Hg – reduces preload and afterload and reduces ischaemia.

- Morphine titrated to patient’s level of consciousness, 5–10 mg IV, accompanied by an anti-emetic, e.g. metochlopramide 10 mg IV – reduces anxiety and preload (venodilation), and reduces myocardial oxygen demand but is also a respiratory suppressant, so caution is required.

- Furosemide 40–80 mg IV – induces venodilation and dieresis.

- Blood tests – urea and electrolytes (U&Es) to ascertain renal function, full blood count (FBC) to ascertain if anaemia is present.

- Chest X-ray – confirms diagnosis and also to ascertain if infection or effusion is present (Figure 11.2).

- May require inotropic support in later stages should hypotension occur to maintain blood pressure, i.e. dobutamine 5 µg/kg/min – increases myocardial contractility.

Figure 11.2 Chest X-ray showing acute heart failure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree