Eating Disorders

Eating disorders are fascinating, confusing, challenging and deeply disturbing. Physicians, nurses, psychotherapists and other medical and mental health providers frequently find themselves confused and feel overwhelmed when dealing with these disorders.

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Differentiate the terms anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and obesity.

Explain why obesity is not categorized as an eating disorder.

Discuss the following theories of eating disorders: genetic or biochemical; psychological or psychodynamic; and family systems.

Discuss the following theories of obesity: genetic or biologic, and behavioral.

Describe at least five clinical symptoms shared by clients with anorexia nervosa and clients with bulimia nervosa.

Differentiate the three personality prototypes of clients with eating disorders that should be considered when planning interventions.

Articulate the rationale for medical evaluation of a client with an eating disorder or the diagnosis of obesity.

State the criteria for inpatient treatment of a client with an eating disorder.

Identify the medical complications of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and obesity.

Construct an assessment tool to identify clinical symptoms of an eating disorder.

Formulate a plan of care for a client with the diagnosis of bulimia nervosa.

Key Terms

Binge eating

Body mass index (BMI)

Cachexia

Developmental obesity

Obesity

Purging

Reactive obesity

Russell’s sign

Eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and obesity are among the most challenging illnesses confronting the mental health profession. They are frequently under-diagnosed and, when diagnosed, clients are often treated incorrectly. Unfortunately, a surprising number of individuals do not seek help. Others will remain ill or die, even after years of treatment (Sobel, 2005).

According to statistics released by Anorexia Nervosa and Related Eating Disorders (ANRED), Inc., about 1% or 1 out of 100 female adolescents between the ages of 10 and 20 years has anorexia. Additionally, approximately 4% or 4 out of 100 college-aged women have bulimia or bulimic patterns. There seems to be an increase in the incidence of middle-aged women with anorexia and bulimia, possibly because this group has consistently considered image to be of major importance. Statistics on males with eating disorders are difficult to find, but estimates are that about 5% to 10% of the individuals diagnosed with anorexia and 10% to 15% diagnosed with bulimia are male. Over the next decade, as public awareness of dieting and eating disorders increases, the number of males seeking treatment for eating disorders is likely to increase. Reliable statistics regarding the prevalence of eating disorders in young children or older adults are limited. Although such cases do occur, they are not common (ANRED, 2006; Frieden, 2004).

At the same time, medical experts warn that America’s weight problem is reaching epidemic proportions. In the United States, approximately 60% of adult Americans, both male and female, are overweight. About 34% are considered to be obese, and many of these individuals have binge eating habits. Furthermore, about 31% of American teenage girls and about 28% of boys are overweight (ANRED, 2006).

The American Heart Association recognizes obesity as a distinct risk factor for heart disease. In 1998, The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute released a report stating that obesity is a complex chronic disease requiring clinician assessment and intervention (Sharp, 1998).

All three disorders may have serious medical consequences if clients remain untreated. However, with proper help, persons with an eating disorder can often learn to stabilize their eating patterns, maintain a healthy weight, and become less preoccupied with food.

Eating disorders are characterized by severe disturbances in eating behavior. Three specific diagnoses exist: anorexia nervosa; bulimia nervosa; and eating disorder, not otherwise specified (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000b). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) has not identified obesity as a psychiatric diagnosis (APA, 2000a). Obesity is considered to be a general medical condition because a consistent association with a psychological or behavioral syndrome has not been established. When there is evidence that psychological factors are of importance in the etiology or course of a particular case of obesity, the diagnosis is listed under psychological factors affecting medical condition. Disorders of feeding and eating that are usually first diagnosed in infancy or early childhood are included in Chapter 29.

Although anorexia is not commonly seen among older adults, the results of the National Diet and Nutrition Survey in London in 1998 revealed that 43% of independent elderly persons consumed fewer than 1,500 calories per day, and 16% to 18% consumed fewer than 1,000 calories per day. This group of individuals are at risk for developing anorexia because of physiologic changes related to aging, pathological conditions (eg, stroke, dental problems), adverse effects of medications (eg, levothyroxine, theophylline), social factors (eg, dependency on others to meet needs), environmental factors (eg, poverty), or psychological conditions (eg, depression) (Endoy, 2005). The issue of involuntary weight loss in the elderly is addressed in Chapter 30.

This chapter focuses on the history of eating disorders; etiology of anorexia, bulimia, and obesity; and addresses the clinical symptoms and diagnostic characteristics of each. Using the nursing process approach, the chapter describes the care of a client with an eating disorder.

History of Eating Disorders

Egyptian hieroglyphics, Persian manuscripts, and Chinese scrolls describe disorders very like what we now call anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Ancient Romans used vomitoriums (lavatory chambers that accommodated vomiting) to relieve themselves after overindulging at lavish banquets. African lore describes voluntary restrictors who refused to

eat during times of famine so that their children would be able to eat. When the famine passed, some of these individuals, who were admired by peers, continued to refuse to eat in spite of the danger of dying. During the 9th century, followers of St. Jerome, who starved themselves in the name of religion, became thin and stopped having menstrual cycles. In Europe, the first formal description of anorexia nervosa in medical literature was made by Richard Morton in 1689. Two other physicians, Lasegue in 1873 in France and Gull in 1874 in England, wrote articles about anorexia nervosa in modern medical literature. During the 19th century, the term anorexia was used, and the psychological aspects of the disease were described. Significant work was provided by the writing and the insight of Hilda Bruch, a physician who assisted in the categorization of anorexia nervosa and began to separate it from other diseases associated with weight loss (ANRED, 2006; Sobel, 2005.)

eat during times of famine so that their children would be able to eat. When the famine passed, some of these individuals, who were admired by peers, continued to refuse to eat in spite of the danger of dying. During the 9th century, followers of St. Jerome, who starved themselves in the name of religion, became thin and stopped having menstrual cycles. In Europe, the first formal description of anorexia nervosa in medical literature was made by Richard Morton in 1689. Two other physicians, Lasegue in 1873 in France and Gull in 1874 in England, wrote articles about anorexia nervosa in modern medical literature. During the 19th century, the term anorexia was used, and the psychological aspects of the disease were described. Significant work was provided by the writing and the insight of Hilda Bruch, a physician who assisted in the categorization of anorexia nervosa and began to separate it from other diseases associated with weight loss (ANRED, 2006; Sobel, 2005.)

Etiology of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia

The prevalence of eating disorders is at an all-time high. Preoccupation with body image, a component of self-concept, has increased over the years as the diet and fitness industry has emphasized that “thin is in.” Pop stars’ clothing styles reinforce the thin, sexy ideal girls strive for. In addition, more skin is shown on television and in the movies than ever before (Irvine, 2001; Tumolo, 2003). The dissatisfaction with body image (ie, a negative self-concept) commonly seen in older children, adolescents, and young adults appears to be fully developed in girls as young as 5 years (Moon, 2001).

Four separate elements of body image as described by Schilder (1950) include:

The actual, subjective perception of the body that an individual forms related to physical appearance and function

A mental picture of one’s body that the individual develops based on internalized feelings and attitudes related to past experiences (eg, a woman who successfully loses 50 pounds and achieves a dress size of 9 still refers to herself as “fat”)

Social experiences or societal stereotype regarding acceptable physical appearance (eg, an adolescent subscribes to a “fitness” magazine and determines that he must reduce his caloric intake and increase his exercise to develop a muscular physique similar to that of the male model in magazine)

An idealized body image that an individual incorporates into one’s mental picture

Body image is changed as one progresses through the different developmental stages of life. Persistent preoccupation with one’s body image can impair emotional and cognitive development, interfere with interpersonal relationships, and place an individual at risk for the development of an eating disorder (Bensing, 2003).

Theories of eating disorders are categorized as genetic or biochemical theories, psychological or psychodynamic theories, and family systems theories. The information presented here summarizes the major concepts discussed in the Harvard Mental Health Letter (Grinspoon, 1997), the Internet Mental Health Web site (http://www.mentalhealth.com/), the Anorexia Nervosa and Related Eating Disorders, Inc., Web site (http://www.anred.com/stats.html), and the National Eating Disorders Association Web site (http://www.nationaleatingdisorders. org/). Other references are cited when additional relevant information was located in literature.

Genetic or Biochemical Theories

Several theories have attempted to describe the causes of eating disorders. According to a study published in the May 2001 issue of Molecular Psychiatry, researchers in Germany and the Netherlands have found that one form of a gene for Agouti-related protein (AGRP), a chemical messenger that stimulates appetite, occurs more frequently among anorexic persons. This discovery suggests that disruptions of the brain’s system for governing food intake contribute to eating disorders (Associated Press, 2001; Sobel, 2005).

A second theory states that eating disorders, including obesity, could be caused by abnormalities in the activity of hormones such as thyroid-stimulating hormone, gonadotropin-releasing hormone, and corticotropin-releasing factors and neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine that preserve the balance between energy output and food intake. According to this theory, nerve pathways descending from the hypothalamus control levels of sex hormones, thyroid hormones, and the adrenal hormone cortisol, all of which influence appetite, body weight, mood, and responses to stress. Research has concluded that genetics is 80% responsible for determining the tendency to become obese (Sadock & Sadock, 2003; Sharp, 1998). Studies of twins indicate

that 50% to 90% are at risk for anorexia and 35% to 83% are at risk for bulimia (DiscoveryHealth.com Disease Center, 2003). Furthermore, individuals with a mother or sister who has anorexia are considered to be 12 times more likely than others with no family history of anorexia to develop it themselves and they are four times more likely to develop bulimia (ANRED, 2006).

that 50% to 90% are at risk for anorexia and 35% to 83% are at risk for bulimia (DiscoveryHealth.com Disease Center, 2003). Furthermore, individuals with a mother or sister who has anorexia are considered to be 12 times more likely than others with no family history of anorexia to develop it themselves and they are four times more likely to develop bulimia (ANRED, 2006).

A third theory speculates that high levels of enkephalins and endorphins, opiate-like substances produced in the body, influence eating disorders. Opioids act on the central nervous system, producing analgesia, change in mood, drowsiness, and mental slowness. Gastrointestinal tract motility and appetite are diminished. These biologic changes may contribute to the denial of hunger in clients with anorexia nervosa. Euphoria is not uncommon because plasma endorphin levels are raised in some clients with bulimia nervosa after vomiting (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

A fourth theory postulates that anorexia results from an imbalance of hormones caused by excessive physical activity. A self-perpetuating cycle develops in which restricted food intake heightens the urge to move, and constantly increasing exercise releases hormones that depress interest in eating.

A fifth theory links the presence of obsessive–compulsive behavior with eating disorders. According to this theory, elevated levels of vasopressin, neuropeptide Y, peptide YY, or a decreased level of cholecystokinin contribute to obsessive–compulsive eating behavior patterns commonly seen in anorexia nervosa.

Recent research has focused on etiological factors including birth trauma (eg, cephalohematoma); preterm birth (eg, less than 32 completed gestational weeks); infection (streptococcus anorexia nervosa); and activity of brain functioning in the right inferior and superior prefrontal lobe and the right parietal regions in women diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, purging type. Further research is needed to verify the role these factors may play in the development of eating disorders (Moore, 2004a; Sobel, 2005).

Psychological and Psychodynamic Theories

A wide range of psychological influences contributing to the development of an eating disorder have been suggested. One theory addresses the theme of starvation as a form of self-punishment, with the unacknowledged purpose of pleasing an introjected or internalized parent. This parent is seen as imposing harsh restrictions on the otherwise well-behaved, orderly, perfectionistic, hypersensitive individual.

A second theory suggests that fasting restores a sense of order to a female who fears the independence of adult femininity (eg, social and sexual functioning) and fears becoming like her mother. Fasting allows the client to exert control over herself and others. The ability to lose weight is a substitute for independence as well as an avoidance of acknowledging one’s sexual desires (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

A third theory notes that individuals starve themselves to suppress or control feelings of emotional emptiness. They struggle for perfection to prove that they do not depend on others to validate their self-concept or self-esteem. Conversely, teenagers with problems managing anger are more likely to engage in bulimic behavior without purging than those who manage anger appropriately (Finn, 2004).

A final theory postulates that females develop an eating disorder because they believe their parents have never responded adequately to their initiatives or recognized individualities. Anorectic females have difficulty distinguishing personal wants from those of others and fear abandonment if they take independent action. Rather than allowing outside influences, including food, to invade them, anorectics deny their needs and will not permit anyone else to control them.

Family Systems Theories

Parents wield a great deal of influence over children’s self-concepts and perceptions of the world. The desire to please parents, on whom we are totally dependent as children, is also extremely powerful. Three theories about family relationships and the development of eating disorders have emerged: conflict between parent–child expectations, family preoccupation with weight and appearance, and “enmeshed” families.

The first theory focuses on parental expectations of children. Parents may emphasize intellectual abilities or athletic talents while ignoring emerging emotional needs of their children. Unfortunately, some children try endlessly to gain the approval of an over-controlling, authoritative, passive, or emotionally distant parent while refusing to acknowledge feelings or ideas that may conflict with or contradict those of the family. Anorectics use the avoidance of food to gain attention and satisfy emotional needs. Bulimic individuals soothe themselves with food.

According to the second theory, both anorectic and bulimic individuals are insecure about their physical shape and size. Preoccupation with weight by parents or siblings close to them can inadvertently set into motion a chain of feelings and events emphasizing external appearances. Thinking that life would be perfect if only they were thinner or more attractive, the individuals assume nurturing or caretaking roles toward siblings or other family members. They fail to see that they want or need nurturing. The family may indirectly encourage this behavior by praising the individual for being strong (Bruch, 2003).

The enmeshed family theory states that families with anorectic daughters are smothering toward their members. The responsibilities of each person and the boundaries among them are indistinct. Everyone is said to be over-responsive to and overprotective of everyone else. Individual needs are not met, feelings are not honestly acknowledged, and conflicts are not openly resolved. As the daughter reaches puberty, the parents are reluctant to make necessary changes in the family rules and roles. Anorexia is considered to be a symptom of a rigid family system’s need and inability to change (Minuchin, 1974).

Researchers have recently focused on the relationship between maladaptive parental behavior and eating disorders. Johnson, Cohen, Kasen, and Brook (2002) investigated childhood adversities, including the issue of childhood sexual abuse, and their role in the development of an eating disorder during adolescence and early adulthood. They identified several experiences that placed children at risk: physical neglect or sexual abuse; low parental affection; low parental communication with the child; low parental time spent with the child; poverty; and low parental education. Living in such a negative environment created an “empty” feeling and loss of control over one’s environment. Consequently, individuals who experienced childhood adversities sought perfection to control their environment in a favorable fashion. Unfortunately, the development of an eating disorder became a solution to the problem.

Etiology of Obesity

Obesity is not a simple problem of will power or self-control, but rather a complex, multifactorial disease. Increasing evidence reveals that genetic, gender, physiologic, psychological, environmental, and cultural factors play a part in the development of obesity (Crouch, 2005). Theories regarding the etiology of obesity are generally grouped into the following categories: genetic or biologic and behavioral theories.

Genetic or Biologic Theories

The first theory, referred to as the set-point theory, proposes that body weight is physiologically regulated like pulse or body temperature. Body weight is maintained as the body self-adjusts its metabolism and its release of hormones (Keesy & Hirvonen, 1997).

A second theory states that heredity or genetic predisposition plays a part in the development of obesity. On the basis of studies of identical and fraternal twins and adopted children, theorists postulate that if a person has one obese parent, the chance of that child becoming obese is 60%; if both parents are obese, the chances increase to 90%. Furthermore, identical twins raised apart are more likely to have similar amounts of body fat than fraternal twins raised separately (Foreyt & Poston, 1997).

A third theory, referred to as the leptin theory, states that an obesity gene directs the formation of leptin (a protein produced by fat cells), which acts on the hypothalamus and influences hunger and satiety. Most obese individuals experience a resistance to leptin’s satiety effect (Albu, Allison, Boozer et al., 1997).

A fourth theory describes the role of medical problems in the development of obesity. Hormonal syndromes such as hypothyroidism, hypercortisolism (Cushing’s syndrome), pseudohypoparathyroidism, and primary hyperinsulinism have been identified as risk factors for obesity, especially in childhood and adolescence (Dietz & Gortmaker, 1984; Faust, 2001).

Recent obesity research at the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia focused on the biology of craving and its influence on nutritional status and the development of obesity. The premise of the research questioned whether food craving is caused by nutrient or caloric deficit. Research findings indicated that nutritional and caloric deprivation were not necessary to create food cravings. They also found that there was almost a tripling or quadrupling of food cravings during the trial when subjects could eat whatever they wanted (Moore, 2004b).

Behavioral Theories

Inactivity has long been recognized as a contributor to obesity. Most clients who have been obese for some

time suffer from an inherited low metabolic rate or resting energy expenditure (REE). One behavioral theory suggests that people may be obese not because they eat too much but because they expend too little energy. This low energy expenditure, coupled with an inactive lifestyle, may cause weight gain or a difficulty in maintaining a healthy weight (White, 2000).

time suffer from an inherited low metabolic rate or resting energy expenditure (REE). One behavioral theory suggests that people may be obese not because they eat too much but because they expend too little energy. This low energy expenditure, coupled with an inactive lifestyle, may cause weight gain or a difficulty in maintaining a healthy weight (White, 2000).

According to research, more than one third of the overweight population, when surveyed, reported that they did not engage in any physical activity during their leisure time. Furthermore, surveys have indicated that children and adolescents participate in fewer than three sessions of vigorous activity per week. Exercise is known to reduce body fat and build healthy muscle mass. Conversely, lack of exercise contributes to obesity (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1996; Whitaker, Pepe, Seidel, & Dietz, 1997; White, 2000).

A second behavioral theory, referred to as the external cue theory, suggests that people eat in response to environmental stimuli. Therefore, as stimuli increase (eg, television commercials regarding food or drink, passing a fast-food restaurant, or certain times of the day associated with eating), individuals eat when they aren’t hungry and they do not stop eating when they are full (James, 2001).

A third behavioral theory focuses on psychosocial factors. An individual may eat in response to emotions such as loneliness, sadness, anger, or celebration. Stressful interpersonal or family dynamics may also be contributing factors (Epstein, Wisniewski, & Weng, 1994).

Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Characteristics of Eating Disorders

Clients with eating disorders share similar clinical symptoms or warning signs including unusual thoughts, feelings, and behavior around food as well as an unhealthy amount of body fat or unhealthy body mass index (BMI). The BMI, an indicator of physical fitness, identifies whether a person is overweight or underweight based on height in relation to weight. Individuals who exhibit a BMI less than 18.4 are considered to be underweight. A normal BMI range is 18.5 to 24.9. An individual with a BMI of 25 to 29.9 is considered to be moderately overweight or preobese. An individual with a BMI of 30 to 34.9 is considered to be moderately obese (Class I Obesity), whereas an individual with a BMI of 35 to 39.9 is considered to be severely obese (Class II Obesity). An individual with a BMI of more than or equal to 40 is deemed to be extremely obese (Class III Obesity) (National Heart, Lung, & Blood Institute, 1998). Box 23-1 provides a formula for calculating BMI and a chart to determine BMI using height and weight.

Examples of clinical symptoms shared by clients with eating disorders include:

Focus on body weight and lack of fat to measure one’s worth

Constant dieting on low-calorie, high-restriction diets (clients who were obese and tried dieting without success)

Impaired body image

Preoccupation with food or refusal to discuss it

Use of food to satisfy negative feelings such as anger, rejection, or loneliness

Compulsive exercising (clients who were obese and tried dieting without success)

Fear of not being able to stop eating

Abuse of drugs or alcohol before bingeing

Stealing, shoplifting, or prostitution to obtain money for food

Clinical symptoms specific to each disorder are discussed within each classification.

Anorexia Nervosa

The client with anorexia nervosa refuses to maintain a normal body weight, intensely fears weight gain, and exhibits a disturbed perception about his or her body. See the accompanying Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Characteristics box.

Statistics indicate that anorexia occurs 10 to 20 times more frequently in females than in males. Most females with anorexia are teenaged girls or women who usually are bright achievers. However, the incidence of males suffering from this disorder has increased. Age has little significance: the diagnosis been made in male clients spanning from as young as 5 years to as old as 70 years (Tumolo, 2003). Characterized by an aversion to food, intense fear of becoming obese, and distorted body image, this disorder may result in death due to serious malnutrition. Of diagnosed anorectic clients, 10% to 20% die. Half of these deaths are due to suicide (Jancin, 1999).

Various methods are used to lose weight. Methods include purging, or attempts to eliminate the body of

excess calories by induced vomiting; abuse of laxatives, enemas, diuretics, diet pills, or stimulants; excessive exercise; or a refusal to eat. Deceitful behavior may prevail as the anorectic client disposes of food that he or she is supposed to eat. Although the following symptoms may occur as the disorder progresses (not all persons who are anorectic exhibit all symptoms), clients rarely seek help unless a medical crisis occurs:

excess calories by induced vomiting; abuse of laxatives, enemas, diuretics, diet pills, or stimulants; excessive exercise; or a refusal to eat. Deceitful behavior may prevail as the anorectic client disposes of food that he or she is supposed to eat. Although the following symptoms may occur as the disorder progresses (not all persons who are anorectic exhibit all symptoms), clients rarely seek help unless a medical crisis occurs:

Box 23.1: Determining BMI

Example: A person who weighs 150 lb and is 5′5″ (65 inches) tall.

BODY MASS INDEX CHART

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | |

| HEIGHT (Inches) | BODY WEIGHT (Pounds) | ||||||||||||||||

| 58 | 91 | 96 | 100 | 105 | 110 | 115 | 119 | 124 | 129 | 134 | 138 | 143 | 148 | 153 | 162 | 167 | 173 |

| 59 | 94 | 99 | 104 | 109 | 114 | 119 | 124 | 128 | 133 | 138 | 143 | 148 | 153 | 158 | 163 | 168 | 173 |

| 60 | 97 | 102 | 107 | 112 | 118 | 123 | 128 | 133 | 138 | 143 | 148 | 153 | 158 | 163 | 168 | 174 | 179 |

| 61 | 100 | 106 | 111 | 116 | 122 | 127 | 132 | 137 | 143 | 148 | 153 | 158 | 164 | 169 | 174 | 180 | 185 |

| 62 | 104 | 109 | 115 | 120 | 126 | 131 | 136 | 142 | 147 | 153 | 158 | 164 | 169 | 175 | 180 | 186 | 191 |

| 63 | 107 | 113 | 118 | 124 | 130 | 135 | 141 | 146 | 152 | 158 | 163 | 169 | 175 | 180 | 186 | 191 | 197 |

| 64 | 110 | 116 | 122 | 128 | 134 | 140 | 145 | 151 | 157 | 163 | 169 | 174 | 180 | 186 | 192 | 197 | 204 |

| 65 | 114 | 120 | 126 | 132 | 138 | 144 | 150 | 156 | 162 | 168 | 174 | 180 | 186 | 192 | 198 | 204 | 210 |

| 66 | 118 | 124 | 130 | 136 | 142 | 148 | 155 | 161 | 167 | 173 | 179 | 186 | 192 | 198 | 204 | 210 | 216 |

| 67 | 121 | 127 | 134 | 140 | 146 | 153 | 159 | 166 | 172 | 178 | 185 | 191 | 198 | 204 | 211 | 217 | 223 |

| 68 | 125 | 131 | 138 | 144 | 151 | 158 | 164 | 171 | 177 | 184 | 190 | 197 | 203 | 210 | 216 | 223 | 230 |

| 69 | 128 | 135 | 142 | 149 | 155 | 162 | 169 | 176 | 182 | 189 | 196 | 203 | 209 | 216 | 223 | 230 | 236 |

| 70 | 132 | 139 | 146 | 153 | 160 | 167 | 174 | 181 | 188 | 195 | 202 | 209 | 216 | 222 | 229 | 236 | 243 |

| 71 | 136 | 143 | 150 | 157 | 165 | 172 | 179 | 186 | 193 | 200 | 208 | 215 | 222 | 229 | 236 | 243 | 250 |

| 72 | 140 | 147 | 154 | 162 | 169 | 177 | 184 | 191 | 199 | 206 | 218 | 221 | 228 | 235 | 242 | 250 | 258 |

| 73 | 144 | 151 | 159 | 166 | 174 | 182 | 189 | 197 | 204 | 212 | 219 | 227 | 235 | 242 | 250 | 257 | 265 |

| 74 | 148 | 155 | 163 | 171 | 179 | 186 | 194 | 202 | 210 | 218 | 225 | 233 | 241 | 249 | 256 | 264 | 272 |

| 75 | 152 | 160 | 168 | 176 | 184 | 192 | 200 | 208 | 216 | 224 | 232 | 240 | 248 | 256 | 264 | 272 | 279 |

| 76 | 156 | 164 | 172 | 180 | 189 | 197 | 205 | 213 | 221 | 230 | 238 | 246 | 254 | 263 | 271 | 279 | 287 |

| Source: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Body Mass Index Table, retrieved from http://wwww.nblbi.nih.gov.easyaccess1.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/guidelines/obesity/bmi.tbl.htm. | |||||||||||||||||

Dry, flaky, or cracked skin

Brittle hair and nails; hair beginning to fall out

Amenorrhea or menstrual irregularity

Constipation

Hypothermia due to loss of subcutaneous fat

Decreased pulse, blood pressure, and basal metabolic rate

Skeletal appearance; BMI of 16 or below

Presence of lanugo (downy-soft body hair seen on newborn infants)

Loss of appetite

Callus formation on finger (Russell’s sign) due to self-induced purging

Dental caries

Total lack of concern about symptoms

Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Characteristics/Anorexia Nervosa

Clinical Symptoms

Refusal to maintain a minimally normal body weight

Intense fear of gaining weight, even with preoccupation with thoughts of food

Significant distortion in perception of body size or shape

Amenorrhea (in women who have established a menstrual cycle)

Depressed mood

Social withdrawal

Irritability

Insomnia

Decreased interest in sex

Inflexible thinking

Strong need to control one’s environment

Diagnostic Characteristics

Maintenance of body weight of less than 85% of what is expected for age and height, or failure in attaining expected weight during growth period

Extreme influence of body weight or shape on one’s self-perception

Denial of seriousness of current extremely low body weight

Absence of three consecutive menstrual cycles

Restricting type: Engagement in activities such as dieting, fasting, or excessive exercise

Binge-eating/purging type: Engagement in binge eating, purging, or both via self-induced vomiting or misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas

The pre-anorectic person is generally considered to be a “model child and student” who is meek, compliant, perfectionistic, and overachieving. The individual usually is overly sensitive, fears independence and sexual relationships, has a low self-concept, and is resistant to growing up and maturing. Starvation is an attention-getting device that permits the anorectic client full control of his or her body, allowing the individual to remain in or revert to a prepubertal state.

Warning signs that should alert parents, teachers, or others to the possibility of anorexia nervosa include the following:

Drastic weight loss in the presence of unusual eating habits, such as fasting, bingeing, or refusal to eat except tiny portions

Obsession with neatness or personal appearance, including frequent mirror gazing. The person constantly checks on his or her appearance, fearing unattractiveness and obesity.

Hostility and the desire to control others

Calorie counting, dieting, and excessive exercise or hyperactivity

Weighing self several times daily

Depressed mood

Amenorrhea or irregular menses

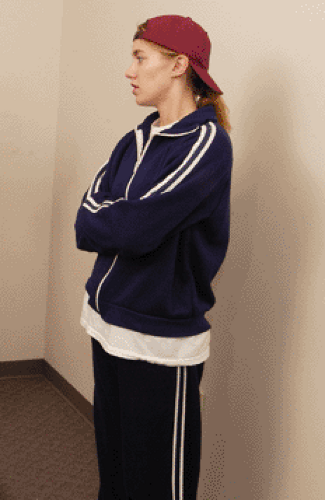

Wearing of loose-fitting clothing to hide physical appearance as it changes (Figure 23-1)

Denial of hunger

As the eating disorder progresses, the anorectic person displays behaviors such as manipulation, stubbornness, hostility, and deceitfulness. Defense mechanisms

used include denial, displacement, projection, rationalization, regression, isolation, and intellectualization. Comorbid psychiatric disorders that occur with anorexia nervosa include depression (65%), social phobia (34%), and obsessive–compulsive disorder (26%) (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

used include denial, displacement, projection, rationalization, regression, isolation, and intellectualization. Comorbid psychiatric disorders that occur with anorexia nervosa include depression (65%), social phobia (34%), and obsessive–compulsive disorder (26%) (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Figure 23.1 The client with anorexia nervosa. Note the layered, baggy clothing to conceal the weight loss. |

According to Erikson’s stages of emotional development, food may become a power struggle between mother and child between the ages of 2 and 3 years. Children between the ages of 4 and 5 years use food to sedate feelings of guilt and powerlessness. A love/trust relationship with food becomes solidified between the ages of 6 and 12 years. Between the ages of 13 and 18 years, food can be controlled with no interference (Erikson, 1993, 1994).

Living in an environment that may be overprotective, rigid, or lacking in conflict resolution, the anorectic person achieves secondary gains such as love and undue attention because he or she is considered to be a special or unique person. See Clinical Example 23-1, The Client With Anorexia Nervosa.

Bulimia Nervosa

Episodic binge eating, a rapid consumption of a large amount of food in less than 2 hours, is classified as bulimia nervosa. The person is aware that the behavior is abnormal, fears the inability to stop eating voluntarily, is self-critical, and may experience depression after each episode. See the accompanying Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Characteristics box.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree