Drugs for Disorders in Women’s Health, Infertility, and Sexually Transmitted Infections

Objectives

• Describe pharmacologic interventions targeting common pathogens causing vulvovaginal infections.

• Describe the mechanism of action for ovulatory stimulation therapy.

Key Terms

amenorrhea, p. 886

anovulatory cycles, p. 887

dysfunctional uterine bleeding, p. 886

dysmenorrhea, p. 888

endometriosis, p. 889

infertility, p. 893

menometrorrhagia, p. 887

menorrhagia, p. 887

metrorrhagia, p. 887

oligospermia, p. 898

pelvic inflammatory disease, p. 888

polycystic ovarian syndrome, p. 887

premenstrual syndrome, p. 890

sexually transmitted infections, p. 886

vaginitis, p. 891

vaginosis, p. 891

varicocele, p. 898

The authors gratefully acknowledge the work of Marcia Welsh, who updated this chapter for the eighth edition.

This chapter discusses the pathophysiology and typical drug regimens for disorders in women’s health, including sexually transmitted infections (STIs). These gynecologic conditions interfere with a woman’s overall health and well-being and may impede a woman’s ability to become pregnant. Many of the medications discussed in Chapter 56 may also be used for relief of menstrual disorders and other gynecologic problems. Drugs for female and male infertility are also addressed, with an emphasis on medications that stimulate ovulation.

Sexually transmitted diseases are a threat to reproductive tract integrity and functioning, and to neonatal health. Not only do STIs affect the short-term and long-term health of a woman and her partner(s), they also are detrimental to the health of a community. Some STIs, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), are life-threatening. Drug therapies that are recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for the treatment of specific STIs are reviewed.

Medications Used to Treat Disorders in Women’s Health

Common reasons women seek gynecologic health care include alterations in menstrual cycle, menstrual or pelvic pain, and changes in vaginal secretions. Included within these broad categories are irregular uterine bleeding, dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome, and vulvovaginal infections. This section describes common disorders in women’s health and presents current pharmacologic approaches to management.

Irregular or Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Irregular uterine bleeding is a term that describes many different medical conditions or pathologies related to the menstrual cycle. Irregular uterine bleeding, also known as abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), is a common reason women seek gynecologic care. AUB encompasses a wide range of variable bleeding patterns in women, such as amenorrhea, menorrhagia, metrorrhagia, menometrorrhagia, intramenstrual bleeding, and dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB).

Amenorrhea

Amenorrhea is the absence of menses. Primary amenorrhea is defined as no menses by age 14 years of age without secondary sex characteristics, or no menses by age 16 years with secondary sex characteristics. Primary amenorrhea may be caused by abnormalities in the structures of the female reproductive tract, chromosomal alterations, or endocrine disorders. Many times the cause is just a physiologic delay in the onset of menstruation. Secondary amenorrhea is the absence of a spontaneous menstrual period for 6 consecutive months in women who have experienced menstrual cycles in the past. Pregnancy is the most common reason a patient may experience amenorrhea, and breastfeeding or menopausal patients also may not menstruate; therefore, secondary amenorrhea is a symptom of these normal physiologic processes. Other causes of secondary amenorrhea include anovulatory cycles (cycles without ovulation), hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, and hyperprolactinemia (high levels of the hormone prolactin, which stimulates lactation). Extreme weight loss and anorexia can also cause amenorrhea.

After assessment of the patient’s health history, a physical examination, and after pregnancy has been ruled out, a progestational challenge test may be administered to determine the underlying cause of amenorrhea. This test uses an oral progestin administered for a limited time to confirm that the hypothalamus-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) responses (the hormonal system mediating the menstrual cycle) are intact.

With the progestational challenge test, a patient is given either micronized progesterone (Prometrium) 400 mg by mouth (PO) at bedtime for 10 days or medroxyprogesterone acetate (Provera) 5 to 10 mg PO for 5 to 10 days. The progestational activity thickens the endometrial lining and increases secretory activity. When the medication is discontinued, progesterone levels decrease, resulting in a breakdown of the endometrial lining and withdrawal bleeding. Withdrawal bleeding should occur within 7 to 10 days after completing the medication and indicates that the HPO axis (the menstrual cycle) is functioning in providing the hormones necessary to regulate the menstrual cycle. Even the smallest amount of bleeding (one incidence of scant spotting) is considered a positive test. However, if there is no withdrawal bleeding, other pathophysiologic problems may exist and further evaluation and diagnostic testing by the health care provider are needed. Micronized progesterone contains peanut oil and thus is contraindicated in those with peanut allergies. The test can also be administered using a combined hormone contraception (CHC) product if the patient desires a form of contraception. The patient starts the CHC method as directed and should have withdrawal menses during the hormone-free phase.

Metabolic Syndrome

Another common cause of secondary amenorrhea is polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). PCOS is a form of metabolic syndrome caused by the oversecretion of luteinizing hormone (LH). LH is the hormone responsible for stimulating ovulation, or mid-cycle release of an ovum from the dominant follicle in the ovary. Oversecretion of LH causes the formation of several follicular cysts in the ovaries instead of one dominant follicle. The presence of several follicles increases estrogen levels; however, ovulation does not occur. The cycle then becomes anovulatory (the absence of ovulation), and the luteal phase, or the second half of the menstrual cycle in which progesterone is dominant, is inhibited. The endometrium of the uterus is exposed to “unopposed” estrogen from the anovulatory cycles. Unopposed estrogen refers to levels of estrogen that are not balanced by a progestational (progesterone) effect. Unopposed estrogen can cause abnormal thickening of the endometrial lining, increasing the patient’s risk for endometrial hyperplasia and uterine cancer. In women experiencing secondary amenorrhea, the incidence of PCOS may approach 30% as the cause of sequentially missed or irregular periods. These patients will complain of skipped menstrual cycles, long menstrual cycles (35 days or greater) or no menstruation for several months.

Insulin resistance is a hallmark of PCOS. Insulin resistance is the body’s inability to respond to elevated glucose levels. Although insulin is secreted when glucose levels are high, “resistance” to the insulin results in altered glucose metabolism and hyperinsulinemia. Hyperinsulinemia causes higher levels of circulating androgens and predisposes the patient to alterations in lipid metabolism, cardiac disease, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Women present with one or more of these symptoms: amenorrhea, hirsutism, acne, acanthosis nigricans (increased pigmentation and thickening of the skin, particularly in skinfold areas), or excessive fat along the midsection of the body. PCOS is a common cause of infertility because of the anovulatory cycles.

Pharmacologic treatment of PCOS depends on whether the patient desires pregnancy. If the patient wants to prevent pregnancy, estrogen-progestin combination contraception products are prescribed if the patient is a candidate. CHC products suppress LH and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) secretion, limit androgen symptoms, and regulate menstruation by providing a withdrawal bleeding period. With the addition of the progestin in the CHC product and a cycling of a monthly (or 4 times per year, depending on product) withdrawal menses, the risks of unopposed estrogen on the endometrium are significantly reduced.

For women who are attempting to conceive, two drugs, metformin and clomiphene citrate, are used. Metformin (Glucophage) inhibits the production of glucose in the liver and increases peripheral cell sensitivity to insulin, effectively treating insulin resistance and decreasing androgen levels. Metformin administration independently regulates the menstrual period and increases the possibility of ovulation. Metformin is initially prescribed as 500 mg, 1 tablet taken PO twice daily (b.i.d.), and may be increased to 850 mg b.i.d. Because metformin may decrease absorption of vitamin B12, women should be assessed for vitamin B12 deficiency. Metformin also has gastrointestinal (GI) side effects (see Chapter 52).

Clomiphene citrate (Clomid or Serophene) is used in conjunction with metformin, or alone to promote a dominant follicle and induce ovulation; it is described in “Medications Used to Promote Fertility.”

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding Patterns

The normal menstrual cycle occurs every 25 to 35 days and lasts 2 to 7 days, with an estimated blood loss of no more than 80 mL. Menorrhagia is regular uterine bleeding greater than 80 mL or lasting more than 7 days. Women with menorrhagia may describe their periods as very heavy or state the need to change a tampon or sanitary pad frequently. Metrorrhagia is irregular uterine bleeding greater than 80 mL or lasting more than 7 days. Women with menorrhagia describe their periods as irregular and heavy. They may state that they have no idea when bleeding will occur, and that when it does happen it will soak through sanitary products or clothing. Menometrorrhagia is a combination of these two. Intramenstrual bleeding is an episode of bleeding, usually light, that occurs between menstrual periods.

A common complaint that brings a woman into the gynecologic health care setting is that she is having menstrual cycles that are suddenly different from the pattern she usually experiences. In women of reproductive age, pregnancy should always be considered first as the possible cause of AUB. However, AUB can result from physiologic processes such as stress, severe dieting and weight loss, eating disorders, or excessive exercise. Irregular bleeding patterns are a sign of decreasing ovarian function or approach of menopause in older women. AUB can also be caused by pathologic processes such as endocrine disorders, thyroid disease, leiomyomata (benign tumors in the uterus), ovarian cysts, infections of the genital tract, or cancer. If a woman is pregnant, uterine bleeding may indicate ectopic pregnancy or impending miscarriage. Some pharmacologic medications, substances, and herbal preparations can also cause irregular bleeding, including anticoagulants, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, hormone therapy, ginkgo, ginseng, and soy products. Once physiologic, pathologic, and pharmaceutic causes have been ruled out, the patient may be diagnosed with DUB.

Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding

DUB is the most common classification of irregular bleeding. Diagnosis of DUB is made when no organic pathology can be determined to cause the irregular bleeding. Pharmacologic treatment of DUB primarily involves normalizing the bleeding pattern and correcting anemia that may have resulted from chronic or acute blood loss. In the normal physiologic menstrual cycle, estrogen and progesterone levels are low during menstruation. Once estrogen levels start to rise with the formation of a dominant follicle, uterine bleeding is effectively stopped, ending menstruation. Increasing levels of estrogen by administration of an extraneous estrogen drug product is usually effective in stopping prolonged DUB.

Since estrogen is never used alone in treatment (because of the detrimental effects of unopposed estrogen on the uterine endometrium and the risk for endometrial cancer), estrogen-progestin combination products are used. Progestins alone are not as effective as estrogen in reducing an episode of acute bleeding; however, because prolonged progestin administration causes atrophy of the endometrial lining, they can be very effective if long-term control is needed. Depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera) intramuscular (IM) injection or IUS/LNG (Mirena) inserted into the uterus are the products used for extended progestin therapy.

Pharmacologic Management of Irregular Bleeding

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used for the treatment of menorrhagia. The mechanism of action for the management of uterine bleeding is not well understood. NSAIDs block the production of prostaglandin, which decreases both excessive bleeding and uterine cramps. Common NSAIDs used for menorrhagia are mefanamic acid (Ponstel), ibuprofen, and naproxen sodium. Only mefanamic acid has U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for menorrhagia. Ibuprofen and naproxen sodium are used by providers as an “off-label” option. The correct dosage of mefanamic acid is 500 mg PO once, followed by 250 mg PO every 6 hours for 2 to 3 days. Mefanamic acid should be taken with food.

CHC products can be used to decrease and regulate DUB. Monophasic products and products that have a dosage schedule of 21/7, 24/4, or 84/7 (see Chapter 56) are first-line drug therapy if the patient is a candidate for CHC products. The increase in estrogen stops uterine bleeding and maintains the endometrial lining. Withdrawal bleeding is cycled in to regulate periods of bleeding. If bleeding does not respond, the CHC can be increased to a schedule of 1 pill PO twice daily for 5 to 7 days, or until the bleeding stops, then 1 pill PO daily for 21 days. Reduction in flow should be seen within 24 hours. If a heavy flow continues for more than 48 hours, the patient should be reevaluated. Benefits, risks, and patient instructions are the same as if the product were being used for contraception. Women who are not a candidate for estrogen therapy or CHC products should excluded. Women using a CHC product for DUB should see their periods normalize within the first 3 months of use. The patient can continue the method for contraception or discontinue use in 6 to 9 months, depending on the effectiveness in controlling bleeding.

Progestins are not as effective as estrogens at reducing episodes of irregular bleeding. However, progestins are effective in the long-term treatment of AUB and may be the method of choice in women who have contraindications to estrogen use. Progestins can be given cyclically (e.g., norethindrone acetate 5 mg PO daily for 10 to 14 days) to produce a monthly withdrawal bleed, or in a continuous dose (e.g., medroxyprogesterone acetate 5 to 10 mg PO daily). Medroxyprogesterone acetate, norethindrone, and micronized progesterone are used in this manner. Depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate and the LNG-IUS are also be used for treatment of DUB. Long-term use of progesterone has an atrophic effect on the uterine endometrium, consequently decreasing incidences of irregular bleeding. Women using depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate or the LNG-IUS for DUB should see heavy bleeding patterns decrease within 3 to 6 months.

Dysmenorrhea

Dysmenorrhea is pelvic pain associated with the menstrual cycle. It is also called cyclic pelvic pain (CPP). Other symptoms that may occur are uterine cramping, lower back pain, abdominal cramps, changes in bowel patterns, increased bowel movements, and nausea and vomiting. Dysmenorrhea is experienced by approximately 80% of women in their late teens and early twenties, when it is more prevalent. It is the most common reason young women miss school or work. Dysmenorrhea is classified as either primary dysmenorrhea or secondary dysmenorrhea, depending on whether there is a known etiology for the menstrual pain. Primary dysmenorrhea is diagnosed when there is no apparent underlying pathology. It is caused by larger-than-normal amounts of prostaglandins at the start of the menstrual period. Prostaglandins cause arterioles in the uterus to contract, decreasing blood flow to the endometrium. All of these mechanisms are necessary for breakdown of the endometrial lining and for menstruation to occur. However, this process causes increased pain in some women.

In secondary dysmenorrhea, there is an underlying cause for the pelvic pain. Conditions that may cause secondary dysmenorrhea are urinary tract infections (UTIs), pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), uterine leiomyomata (fibroids), and endometriosis.

Pharmacologic Management of Dysmenorrhea

Herbal, Botanical, and Vitamin/Mineral Therapy.

The following vitamin therapy may provide pain relief in patients with mild dysmenorrhea: vitamin E (400 to 800 units/day), magnesium (dose ranges varied in clinical trials), thiamine (vitamin B1, 100 mg/day), and zinc (1 to 3 mg/day a few days before menstruation). Omega-3 fatty acids (1 to 2 g/day) decreased the use of ibuprofen in women with dysmenorrhea in small clinical trials. Omega-3 fatty acids must be used with caution in individuals on anticoagulant therapy.

NSAIDs.

NSAIDs block pain by preventing synthesis of prostaglandins. The mechanism of drug action is the inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX). The COX enzyme converts arachidonic acid into prostaglandins, which cause constriction of the uterine arterioles, necrosis of the endometrial lining, uterine contractions, and menstrual pain. Usually nonselective and COX-2 inhibitors are used. The most commonly used NSAIDs for relief of pain associated with dysmenorrhea include naproxen sodium (Anaprox), diclofenac potassium (Cataflam), ibuprofen (Motrin), naproxen (Naprosyn), celecoxib (Celebrex), and mefenamic acid (Ponstel). Many NSAIDs can be purchased over the counter, so the nurse should include health information about the benefits, risks, and alternatives as well as specific dosage amounts, other drug interactions, and how to take the medication. Some (diclofenac potassium, celecoxib, and mefenamic acid) are by prescription only. Patients must understand the differences in these medications and avoid them if they have allergies to and/or side effects from any of the ingredients. They should avoid taking two different NSAID medications at the same time. GI upset is a common side effect of NSAIDs, so most drugs in this category should be taken with food and water. NSAIDs can also be taken with an antacid or calcium supplement to prevent GI upset. NSAIDs should not be taken for more than 10 days.

Hormonal Contraception.

CHC products are effective in the treatment of dysmenorrhea. Extended-cycle CHC products such as 24/4 day products or 87/7 day products may be more effective. CHC products limit the thickness of the uterine endometrium. The 24/4 day CHC products shorten withdrawal bleeding periods, and the extended-cycle CHC products decrease the number of withdrawal menses per year or eliminate them altogether. Depo-Provera, Implanon, and the LNG-IUS decrease dysmenorrhea in patients who are candidates for these methods. Long-term progestin-only products cause atrophy of the uterine lining, limiting the occurrence of dysmenorrhea and the amount of bleeding during menstruation.

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is the abnormal location of endometrial tissue outside the uterus. The tissue is known as ectopic endometrial implants. It is a common cause of dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility. The ectopic endometrial implants can be found affixed to the ovaries, the posterior surface of the uterus, the uterosacral ligaments, the broad ligaments, or the bowel. They also can be found on other organs within the pelvic or thoracic cavity. The ectopic endometrial implants respond to hormonal control, particularly estrogen, in the same way as the normal endometrial tissue located inside the uterus. Thus, when menstruation occurs, the ectopic endometrial implants proliferate and then bleed. As the number of menstrual cycles increases, inflammation of surrounding organ tissue, scar tissue formation, and adhesions result, causing pelvic pain.

Diagnosis of endometriosis is based on laparoscopic evidence of endometrial tissue, or implants, outside the uterus. The most common symptoms of endometriosis are dysmenorrhea and pelvic pain, sometimes including chronic pelvic pain, which lasts more than 6 months and is not associated specifically with menstruation. The patient may experience back pain; painful, sometimes bloody, bowel movements; and dyspareunia (painful sexual intercourse). An increased number of women with endometriosis experience primary or secondary infertility; although a specific cause linking the two has not been established. It is theorized that the ectopic endometrial implants, or the resultant scar tissue and adhesions, obstruct or affect the motility of the fallopian tubes or other reproductive organs. Affected women have an increased risk for ectopic pregnancy.

Pharmacologic Management of Endometriosis

Pharmaceutic treatment strategies for endometriosis include drugs that decrease the amounts of circulating estrogen and limit or eliminate menstruation. This interrupts internal bleeding and irritation associated with the ectopic endometrial implants and may even cause them to recede.

CHC Products.

These drugs suppress gonadotropin-releasing hormone (Gn-RH) release, prevent ovulation, and cause atrophy of the uterine lining, actions thought to relieve pelvic pain by causing a regression of the endometrial implants. CHCs relieve the pain of endometriosis in approximately 75% of women. Extended-cycle CHC products can also manage endometriosis by causing fewer cycles per year or eliminating withdrawal menses altogether.

Progestational Products.

These drugs suppress ovulation and cause long-term endometrial atrophy. They also inhibit Gn-RH release, similar to CHCs. Over time, progestins can shrink or eliminate endometrial implants. The most commonly used progestin is depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) in the form of Depo-Provera and Depo-subQ 104 Provera. With DMPA, 70% to 90% of patients experience relief of symptoms associated with endometriosis. This effect may last months after discontinuing the medication. Benefits and risks are the same as if using DMPA for contraception, so concerns for bone mineral density (BMD) loss and prevention, irregular bleeding or amenorrhea, possible weight gain, and mood changes should be discussed with the patient (see Chapter 56). The injection is given every 11 to 13 weeks.

A progestin that can be taken in an oral form is norethindrone acetate (Aygestin), 5 mg PO daily for 2 weeks, then increasing the dose by 2.5 mg every 2 weeks until a dose of 15 mg per day is reached. This is continued for 6 to 9 months.

Gn-RH Agonists.

Gn-RH agonists are potent drugs that inhibit Gn-RH release and create a hypoestrogenic environment. The side effects are also menopause-like, with hot flashes, atrophic vaginitis, vaginal dryness, decreased sex drive, and potential for bone loss. Leuprolide (Lupron Depot 3.75 mg) is given in a 3.75-mg dose IM monthly for up to 6 months. Leuprolide is also available in a 3-month dosage schedule (Lupron Depot-3 Month 11.25 mg) given via IM injection once every 3 months for up to 6 months. Leuprolide should be initiated in the first 3 days of the menstrual cycle as it is pregnancy category X. Women may be able to become pregnant on leuprolide, so a barrier method of contraception should be used. Progestins or CHC products can also be prescribed to prevent pregnancy and reduce bone loss.

Nafarelin (Synarel Nasal Spray) is administered in a 400-mcg/day dose; with 1 spray (200 mcg) into one nostril in morning and 1 spray (200 mcg) into the other nostril in evening for up to 6 months. Goserelin (Zoladex) is administered in a 3.6-mg dose in a subcutaneous implant placed in the abdominal wall every 28 days for 6 months. The Gn-RH agonists should be used for only 6 months. Use of these medications past 6 months, as well as retreatment, can cause irreversible adverse changes in BMD. Approximately 90% of women experience relief of symptoms with gonadotropin inhibitors and Gn-RH agonists.

![]() Studies investigating DMPA preparations compared with Gn-RH inhibitors/agonists report that Depo-SubQ 104 Provera is as effective as leuprolide in reducing symptoms of endometriosis and shrinking or eliminating endometrial implants. DMPA preparations are much less expensive for the patient than leuprolide. Leuprolide causes a higher hypoestrogen state than DMPA; therefore, menopause-like symptoms are much more severe. DMPA, in studies, caused irregular bleeding including menorrhagia, weight gain, and prolonged time returning to menstruation after the treatment was discontinued. DMPA also causes BMD changes, and preventive measures must be reviewed with the patient before initiating treatment.

Studies investigating DMPA preparations compared with Gn-RH inhibitors/agonists report that Depo-SubQ 104 Provera is as effective as leuprolide in reducing symptoms of endometriosis and shrinking or eliminating endometrial implants. DMPA preparations are much less expensive for the patient than leuprolide. Leuprolide causes a higher hypoestrogen state than DMPA; therefore, menopause-like symptoms are much more severe. DMPA, in studies, caused irregular bleeding including menorrhagia, weight gain, and prolonged time returning to menstruation after the treatment was discontinued. DMPA also causes BMD changes, and preventive measures must be reviewed with the patient before initiating treatment.

Aromatase inhibitors (nastrozole, letrozole) suppress the conversion of androgens into estrogens and are prescribed for up to 6 months.

Premenstrual Syndrome

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) comprises a collection of cyclic physical symptoms and perimenopausal mood alterations. Symptoms increase in the 2 weeks before menstruation and subside after menses begins. These physical, emotional, and behavioral symptoms interfere to varying degrees with a woman’s ability to function. PMS falls under the classification of cyclic perimenstrual pain and discomfort.

PMS can result in decreased work effectiveness and distressing mood variations. PMS affects 40% of all adult women, with about 5% exhibiting debilitating symptoms. These debilitating symptoms may be classified as premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) if severe mood swings are exhibited. PMDD is recognized by the American Psychiatric Association as a “depressive disorder not otherwise specified.” The hallmark of PMS and PMDD is that symptoms occur in a repetitive pattern during the luteal phase (days 15 to 28) of the menstrual cycle and decrease significantly in the early follicular phase (days 1 to 14).

There is no universal agreement about the definition, etiology, symptoms, or treatment of PMS. Researchers theorize that the etiology of PMS could be hormonal excess or deficits, fluid or sodium retention, or nutritional deficiencies. It is also proposed that an imbalance in the HPO axis function exists. Other hypotheses center on the neuroregulatory effects of estrogen and progesterone on the release or uptake of serotonin.

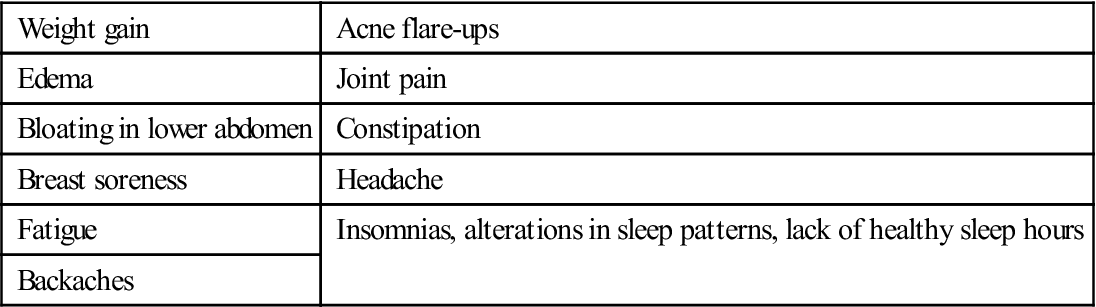

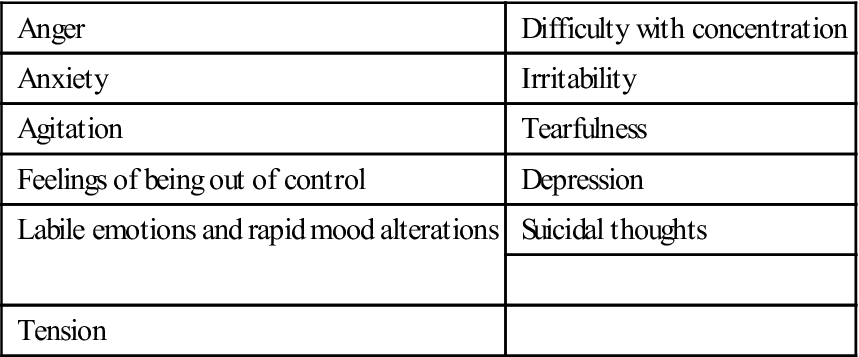

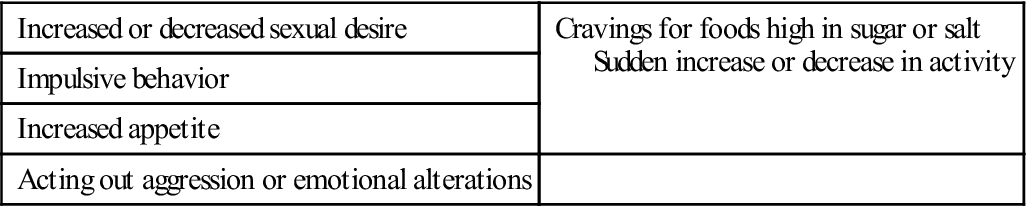

A patient can help with the diagnosis of PMS by recording three variables on a perimenstrual assessment calendar: (1) group of symptoms (Box 58-1), (2) severity of symptoms, and (3) impact on function (degree of distress). Diagnosis of PMS can be made when the patient’s symptoms consistently occur in a cyclic pattern at least 1 week before the menstruation cycle and decrease significantly after menses begins. Symptoms usually have a negative impact on the ability to function effectively. Other endocrine abnormalities must be ruled out. Also, it should be noted that not every symptom associated with the menstrual cycle is indicative of PMS.

Pharmacologic and Complementary and Alternative Treatment of PMS

Pharmacologic treatment of PMS should consider evidence-based recommendations that are appropriate in treating the patient’s specific symptoms. The following treatments have been identified.

Nonpharmacologic Treatment.

Nonpharmacologic treatment modalities are very important in treating women with PMS. They include expression of empathy, support from family and friends, correction of knowledge deficits about PMS, exercise, and dietary changes. Aerobic exercise improves general health, heightens endorphin levels, and may facilitate an overall sense of well-being. Dietary changes include limiting salty foods, alcohol, caffeine, and concentrated sweets. Eating four to six small, high-carbohydrate, low-fat meals may also help relieve some symptoms. Stress-reduction exercises are also helpful. These measures may help the patient feel proactive regarding her diagnosis of PMS.

Herbal, Botanical, and Vitamin/Mineral Therapy.

Some patients experience improvement with selected symptoms through use of vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), which is popular but not found superior to placebo. Increased calcium intake through diet, not via supplementation, has also been suggested for symptom relief of PMS. Studies indicate that calcium has an inverse relationship with PMS: the higher the intake of calcium, the lower the PMS risk. Since calcium and B6 are relatively benign when taken in the recommended allowances, both can be used by women to treat PMS symptoms.

Studies on evening primrose oil have had mixed results, although supporters say that it lessens premenstrual mood alterations, helps alleviate breast tenderness, and decreases fluid retention. Chasteberry may help with some PMS symptoms as well as breast pain. Chasteberry prevents progesterone overproduction and inhibits prolactin release (prolactin may be elevated in women with breast tenderness).

St. John’s wort has demonstrated efficacy for mild depression that may accompany PMS and PMDD. The mechanism of action is unclear. St. John’s wort should not be used if the patient is taking monoamine oxidase inhibiters or has been prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Many herbal or botanical supplements have variations in active ingredient dosing and purity because they may not be approved by the FDA for a specific use.

Antidepressant and Antianxiety Medications.

Severe PMS is improved with SSRIs or SSRI medications. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists suggests that SSRIs be taken either continuously or cyclically on days 15 to 28 of the menstrual cycle. Symptom relief includes a decrease in irritability, mood swings, fatigue, tension, and breast tenderness. SSRIs block the reuptake of serotonin into nerve terminals in the CNS, regulating serotonin use by the brain. The most commonly used SSRIs are fluoxetine hydrochloride (Prozac) and sertraline hydrochloride (Zoloft), although paroxetine hydrochloride (Paxil) and citalopram (Celexa) have also demonstrated relief in patients with severe PMS symptoms. Fluoxetine has been repackaged and remarketed to women as Sarafem.

For the management of severe PMS or PMDD, antianxiety medications may be prescribed to reduce or eliminate anxiety and control panic disorders. Antianxiety medications may also help with depression and headaches associated with PMS. The most commonly used medications include alprazolam (Xanax), diazepam (Valium), lorazepam (Ativan), and buspirone (BuSpar). These medications should be used in the short term because of their potential for tolerance or addiction. Patients should be warned that they also may cause sedation. Antianxiety medications are not recommended as first-line of treatment for severe PMS. Treatment for longer than 8 weeks warrants continued medical or psychiatric surveillance.

Hormonal Therapy.

Long-term suppression of ovulation has been shown to decrease cyclic physical discomforts and normalize mood variations in some women. Monophasic CHC products such as oral contraception pills, Ortho-Evra, and Nuva Ring can be used in this manner. Caution should be used with progestin-only products because they may exacerbate symptoms of depression. Oral contraceptives such as Yaz, Beyaz, and Lybrel are approved by the FDA for treatment of PMDD.

Common Vulvovaginal Infections

Another common reason women seek out gynecologic care is changes in vaginal secretions or vulvar and vaginal pruritus, irritation, or pain. Vaginal secretions are normal, may change throughout a women’s menstrual cycle, lubricate the vaginal and external genitalia, and maintain a healthy vaginal microecosystem. Normal vaginal secretions are clear to white, may be slightly slippery or sticky, and have a mild odor; the secretions may turn yellow on underwear or panty liners. Three vaginal infections change normal vaginal secretions into abnormal vaginal discharge and cause different vulvar or vaginal symptoms: vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), bacterial vaginosis (BV), and trichomoniasis. Vaginitis is the term used to describe inflammation in the vaginal area.

Vulvovaginal Candidiasis.

VVC is a yeast infection of the vulva or vaginal area. It causes inflammation, irritation, pruritus, excoriations, and burning on urination or intercourse, and it usually presents with a thick, white, curdlike discharge. The causative agent is most often an overgrowth of Candida albicans, normal flora in the vagina; other Candida species can also cause VVC. Uncomplicated VVC is treated with topical drugs from the azole category. There are 1-day antifungal agents, as well as 3- and 7-day vaginal treatments. Some antifungal medications can be purchased over the counter; others need a prescription. Table 58-1 lists common medications used to treat VVC.

TABLE 58-1

COMMON VAGINAL INFECTIONS AND PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT

| INFECTION | CDC-RECOMMENDED REGIMENS | NOTES |

| Vulvovaginal Candidiasis | ||

| Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis may be indicative of other disease, such as diabetes or HIV infection. | ||

| Vaginal Preparations with Butoconazole | ||

| Femstat-3 (OTC) | Butoconazole 2% cream 5 g intravag for 3 d or | Pregnancy category: C Number following brand name indicates number of days product is to be used. |

| Gynezole-1 (Rx only) | Butoconazole 2% cream 5 g (Butaconazole-1) single intravag application | All suppositories and creams listed are inserted intravaginally. |

| Vaginal Preparations with Clotrimazole | ||

| Gyne-Lotrimin 7 Cream (OTC) | Clotrimazole 1% cream 5 g intravag for 7-14 d or | Pregnancy category: B |

| Gyne-Lotrimin 7 Combination Pack (OTC) | Clotrimazole 100-mg vag tab for 7 d or | |

| Gyne-Lotrimin 3 Cream (OTC) | Clotrimazole 100-mg vag tab, 2 tab for 3 d | |

| Vaginal Preparations with Miconazole | ||

| Monistat-7 Cream (OTC) | Miconazole 2% cream 5 g intravag for 7 d or | Monistat comes in a variety of products, cream only, vaginal suppository only, and combination packs with both vaginal suppositories and cream. Pregnancy category: C; use is not recommended in first trimester. Number following brand name indicates number of days product is to be used. |

| Monistat-7 Suppositories (OTC) | Miconazole 100-mg vag supp, 1 supp for 7 d or | |

| Monistat-3 Suppositories (OTC) | Miconazole 200-mg vag supp, 1 supp for 3 d or | |

| Monistat-1 Combination Pack (OTC) | Miconazole 1,200-mg vag supp, 1 supp for 1 d | |

| Vaginal Preparations with Nystatin | ||

| Nystatin (Rx only) | Nystatin 100,000-unit vag tab, 1 tab for 14 d | Pregnancy category: A |

| Vaginal Preparations with Terconazole | ||

| Terazol 7 Cream (Rx only) | Terconazole 0.4% cream 5 g intravag for 7 d or | Pregnancy category: C |

| Terazol 3 Cream | Terconazole 0.8% cream 5 g intravag for 3 d or | |

| Terazol 3 Suppositories | Terconazole 80-mg vag supp, 1 supp for 3 d | |

| Vaginal Preparations with Tioconazole | ||

| 1-Day (OTC) | Tioconazole 6.5% ointment 1 applicatorful in a single dose | Pregnancy category: C |

| Vagistat-1 Ointment (OTC) | Tioconazole 6.5% ointment 1 applicatorful in a single dose | Complete relief may take up to 7 days. |

| Oral Preparations | ||

| Diflucan (Rx only) | Fluconazole 150-mg oral tablet, one tab PO in a single dose | Pregnancy category: D |

| Bacterial Vaginosis | ||

| Clindamycin | ||

| Cleocin Vaginal Cream (Rx only) | Clindamycin cream 2% 1 full applicator (5 g) intravag h.s. for 3-7 d or | Pregnancy category: B |

| Cleocin Vaginal Ovules (Rx only) | Clindamycin ovules 100 mg intravag h.s. for 3 d or | |

| Clindesse (Rx only) | Clindamycin cream 2% 1 full applicator intravag in a single dose or | |

| Oral Clindamycin | Clindamycin 300 mg PO b.i.d. for 7 d | |

| Metronidazole | ||

| Flagyl ER Oral Tablets (Rx only) | Metronidazole 750-mg tab PO for 7 d or | Pregnancy category: B All ETOH products should be avoided when taking oral metronidazole during treatment and for 3 days after use. Should be taken with food. Oral metronidazole should not be used in first trimester of pregnancy. Second and third trimester: Pregnancy category: B |

| Flagyl (Rx only) | Metronidazole 500 mg PO b.i.d. for 7 d or | |

| Flagyl (Rx only) | Metronidazole 2 g PO in a single dose or | |

| MetroGel Vaginal (Rx only) or Vandazole (Rx only) | Metronidazole vaginal 0.75% gel 1 full applicator 1-2 times/d for 5 d | |

| Tinidazole | ||

| Tindamax (Rx only) | 250-mg or 500-mg tabs 2 grams daily PO for 2 d or 1 gram daily PO for 5 d | When taking oral tinidazole, avoid all ETOH products during treatment and for 3 days after use. Take with food. Do not use oral tinidazole in the first trimester of pregnancy. Second and third trimester: Pregnancy category: B Fewer GI side effects than metronidazole |

| Tinidazole 2 g/d for 2 d or 1 g/d for 5 d | ||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree