Identify the various factors associated with obesity.

Describe the clinical manifestations of obesity.

Describe the clinical manifestations of obesity.

Identify the prototype drug from each drug class used to manage obesity.

Identify the prototype drug from each drug class used to manage obesity.

Describe the anorexiants used in weight management in terms of their action, use, contraindications, adverse effects, and nursing implications.

Describe the anorexiants used in weight management in terms of their action, use, contraindications, adverse effects, and nursing implications.

Describe the lipase inhibitors used in weight management in terms of their action, use, contraindications, adverse effects, and nursing implications.

Describe the lipase inhibitors used in weight management in terms of their action, use, contraindications, adverse effects, and nursing implications.

Understand how to apply the nursing process in the care of patients who are overweight or obese.

Understand how to apply the nursing process in the care of patients who are overweight or obese.

Clinical Application Case Study

Halli Vargas is a 31-year-old woman who has had a weight problem all her life. She has been on any number of diets that have a “yo-yo” effect, with weight loss followed by weight gain. She stands 5 ft 5 inches tall and weighs 265 pounds. Her nurse practitioner starts her on orlistat and prescribes a consultation with a dietitian.

KEY TERMS

Anorexiant: drug that suppresses the appetite.

Body mass index (BMI): reflection of weight in relation to height; better indicator than weight alone for determining the fitness level of a person.

Central obesity: concentration of fat in abdominal area resulting in an increase in waist size

Obesity: BMI of 30 or more kg/m2

Overweight: BMI of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2

Introduction

Obesity, which affects 34% of the adult population in the United States, has reached epidemic proportions. It is associated with multiple chronic diseases. Excessive amounts of any of the dietary nutrients are converted to fat and stored in the body, resulting in excess weight and obesity. Although therapeutic lifestyle changes are the cornerstone of population-based interventions to manage obesity, they are often insufficient in achieving recommended treatment targets. Once the agents are discontinued, people may regain weight. The importance of a safe and effective use of drugs coupled with therapeutic lifestyle changes has become critical. This chapter discusses obesity and weight management, specifically focusing on drugs to aid weight loss and maintain desired weight.

Overview of Weight Management

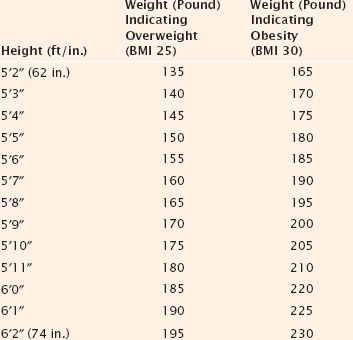

A better indicator of weight problems than weight alone, body mass index (BMI) reflects weight in relation to height. Overweight is defined as a BMI of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2. Obesity is defined as a BMI of 30 or more kg/m2. The desirable range for BMI is 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2, with any values below 18.5 indicating underweight and any values of 25 or greater indicating excessive weight (Box 34.1). A large waist circumference (greater than 35 inches for women, greater than 40 inches for men) is another risk factor for overweight and obesity. Using these definitions, it is projected that 68% of adults in America are overweight and 34% are obese.

BOX 34.1 Calculation of Body Mass Index (BMI) and Height and Weight Indicators for Overweight and Obese

BMI

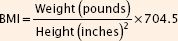

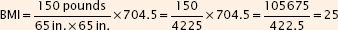

BMI calculators are available online (http://www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi/) but can be calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters, squared; or as weight in pounds divided by height in inches, squared, multiplied by a conversion factor of 704.5 (listed as 703 in some sources), as follows:

For example: A person who weighs 150 pounds and is 5 ft 5 inches (65 inches) tall

Weight Compared With Height as an Indicator for Being Overweight or Obese

Etiology

Carbohydrates, proteins, and fats are required for human nutrition. Either deficiencies or excesses impair health, cause illness, and interfere with recovery from illness or injury. Carbohydrates and fats serve primarily as sources of energy for cellular metabolism, and proteins are basic structural and functional components of all body cells and tissues. Energy is measured in kilocalories (kcal, commonly called calories) per gram of food oxidized in the body. Carbohydrates and proteins supply 4 kcal/g. Fats supply 9 kcal/g. Excessive amounts of any nutrient are converted to fat and stored in the body, resulting in excess weight and obesity.

The incidence of overweight and obesity has dramatically increased during the past 25 years. Obesity may occur in anyone but is more likely to occur in women, ethnic groups, and people of lower socioeconomic status. In general, more women than men are obese, whereas more men than women are overweight. African American women and Mexican American men and women have the highest rates of overweight and obesity in the United States. Women in lower socioeconomic classes are more likely to be obese than those in higher socioeconomic classes.

The etiology of excessive weight is thought to involve complex and often overlapping interactions among physiologic, genetic, environmental, psychosocial, and other factors.

Physiologic Factors

In general, increased weight is related to an energy imbalance in which energy intake (food/calorie consumption) exceeds energy expenditure. Total energy expenditure represents the energy expended at rest (i.e., the basal or resting metabolic rate), during physical activity, and during food consumption. When a person ingests food, about 10% of the energy content of that food is expended in the digestion, absorption, and metabolism of nutrients. Foods that contain carbohydrates and proteins stimulate energy expenditure; high-fat foods have little stimulatory effect. The energy required to metabolize and to use food reaches a maximum level about 1 hour after the food is ingested. In addition, men tend to expend more energy than women because they have proportionally more muscle mass. Energy expenditure usually decreases in older men and women of all ages because these groups have less muscle tissue and more adipose tissue. Muscle is more metabolically active (i.e., has higher energy needs and burns more calories) than adipose tissue.

Excessive weight can result from eating more calories, exercising less, or a combination of the two factors. Consuming an extra 500 calories each day for a week results in 3500 excess calories or one pound of fat. Excess calories are converted to triglycerides and stored in fat cells. With continued intake of excessive calories, fat cells increase in both size and number.

Genetic Factors

Various studies indicate that a significant portion of weight variation within a given environment is genetic in origin. For example, identical twins raised in separate environments often have similar body types. Most cases of human obesity are attributed mainly to the combination of genetic susceptibility and environmental conditions.

Environmental Factors

Environmental factors contributing to the greater number of overweight and obese people include increased food consumption and decreased physical activity. The ready availability and relatively low cost of a wide variety of foods, in addition to large portion sizes and high-calorie foods, promote overeating. In addition, many social gatherings are associated with eating or overeating.

In relation to physical activity, usual activities of daily living for many people, including work-related activities, require relatively little energy expenditure. In addition, few Americans are thought to exercise in the optimal frequency, intensity, or duration to maintain health and prevent excessive weight gain. For both adults and children, increased time watching television, playing video or computer games, and working on computers contribute to less physical activity and are thought to promote weight gain and obesity. In general, however, it is still unknown whether less physical activity leads to obesity or the physical effects of obesity lead to minimal physical activity.

Psychosocial Factors

Psychosocial disorders may be either a cause or an effect of obesity. Although much is still unknown about the psychological aspects of obesity development, depression and/or abuse may play a role. Obese people often report symptoms of depression, and some people overeat and gain weight during depressive episodes. It may be that obesity and depression commonly occur together and reinforce each other. A depressed person is less likely to take the active measures in diet and exercise that are required to lose weight, even if obesity is a prominent factor in the development of depression.

Other Factors

Diseases are rarely a major cause of the development of obesity. However, numerous disease processes may limit a person’s ability to engage in calorie-burning physical activity. In addition, numerous prescription medications reportedly cause weight gain in some or most of the patients who take them (Box 34.2).

BOX 34.2 Effects of Selected Medications on Weight

Antidepressants

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as fluoxetine (Prozac, Sarafem) and related drugs, may promote weight loss with short-term use. However, with long-term use, they reportedly may cause as much weight gain as tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) such as amitriptyline (Elavil). TCAs have long been associated with excessive appetite and weight gain. Mirtazapine (Remeron) and phenelzine (Nardil) are also associated with weight gain. The effects of bupropion (Well-butrin and Zyban) on weight are unclear from clinical trials. Gain was reported when bupropion was used as a smoking deterrent, but both gain and loss occurred when used as an antidepressant. However, anorexia and weight loss occurred at a higher percentage rate than increased appetite and weight gain.

Antidiabetic Drugs

Although little attention is paid to the topic in most literature about diabetic drugs, weight gain apparently occurs with insulin, sulfonylureas, and the glitazones (but not with metformin, acarbose, or miglitol). Almost all patients with type 2 diabetes eventually require insulin; those who are failing on oral agents generally gain a large amount of body fat when switched to insulin therapy. Although the mechanism of weight gain is unknown, it may be related to the chronic hyperinsulinism induced by long-acting insulins and the sulfonylureas (which increase insulin secretion). Less weight is gained when oral drugs are given during the day and an intermediate- or long-acting insulin is injected at bedtime. This strategy is thought to cause less daytime hyperinsulinemia than the more traditional insulin strategies.

For near-normal-weight patients with diabetes who require drug therapy, a sulfonylurea may be given. However, for obese patients, metformin is usually the initial drug of choice because it does not promote weight gain. Metformin may also be used to treat obese diabetic children, aged 10 to 16 years, who require drug therapy.

Antiepileptic Drugs

Weight gain commonly occurs with the use of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). This has been observed for many years with older drugs (e.g., phenytoin, valproic acid, carbamazepine) and with newer AEDs (e.g., gabapentin, lamotrigine, tiagabine). Mechanisms by which the drugs promote weight gain are unclear but may involve stimulation of appetite and/or a slowed metabolic rate. Consequences of weight gain may include increased risks of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and other physical health problems as well as psychological distress over appearance, especially in children and adolescents.

Antihistamines

Histamine, (H,) antagonists (e.g., diphenhydramine, loratadine) reportedly increase appetite and cause weight gain.

Antihypertensives

The main antihypertensive drugs reported to cause weight gain are the beta blockers. The drugs can cause fatigue and decrease exercise tolerance and metabolic rate, all of which may contribute to weight gain. Other mechanisms may also be involved. As a result, some clinicians question the use of beta blockers in overweight or obese patients with uncomplicated hypertension. Alpha blockers may also cause weight gain, but apparently at a low incidence. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and calcium channel blockers are not reported to promote weight gain.

Antipsychotics

Weight gain is often reported and extensively documented with antipsychotic drugs. Although the exact mechanism is unknown, weight gain has been associated with antihistamine effects, anticholinergic effects, and blockade of serotonin receptors. In addition, dietary factors and activity levels may also play significant roles.

Clozapine and olanzapine reportedly cause significant weight gain in 40% or more of patients. Compared with clozapine and olanzapine, risperidone causes less weight gain, and quetiapine and ziprasidone cause the least weight gain. Weight gain may lead to noncompliance with drug therapy. In addition to weight gain, clozapine and olanzapine adversely affect glucose regulation and can aggravate preexisting diabetes or cause new-onset diabetes. The extent to which these effects are related to weight gain is unknown. For patients who are obese, diabetic, or at risk of developing diabetes, an antipsychotic drug that causes less weight gain would seem the better choice.

Cholesterol-Lowering Agents

Weight gain has been reported with the statin group of drugs; mechanisms and extent are unknown.

Corticosteroids

Systemic corticosteroids may cause increased appetite, weight gain, central obesity, and retention of sodium and fluid. Inhaled and intranasal corticosteroids have little effect on weight.

Gastrointestinal Drugs

Increased appetite and weight gain have been reported with the proton pump inhibitors such as omeprazole and others. The mechanisms and extent are unknown.

Hormonal Contraceptives

The weight gain associated with using hormonal contraceptives may be related more to retention of fluid and sodium than to increased body fat.

Mood-Stabilizing Agent

Weight gain has been reported with long-term use of lithium, with approximately 20% of patients gaining 10 kg (22 pounds) or more. This increased weight is attributed to fluid retention, consumption of high-calorie beverages as a result of increased thirst, or a decreased metabolic rate. Weight gain is a common reason for noncompliance with lithium therapy, and weight gain may be more common in women with lithium-induced hypothyroidism and in those who are already overweight.

Age Considerations

Overweight and Obese Children

Being overweight and obese are common and increasing among children and adolescents in epidemic proportions. It is estimated that nearly 25% of children and adolescents in the United States are overweight. Overweight is defined as a BMI above the 85th percentile for the age group and obesity as a BMI above the 95th percentile.

Childhood obesity is a major public health concern because these children have or are at risk of developing hypertension, dyslipidemias, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and other disorders that may lead to reduced quality of life, major disability, and death at younger adult ages than nonobese children. Obesity, type 2 diabetes, and other health problems are mainly attributed to poor eating habits and too little exercise. In addition, the child who is obese after 6 years of age is highly likely to be obese as an adult and develop obesity-related health problems, especially if a parent is obese. Obesity in adults that began in childhood tends to be more severe.

Under pressure from parents and advocates to prevent obesity in youth, many school districts have banned soft drinks, candy, and junk foods from school vending machines and cafeterias. The American Beverage Association agreed to a voluntary ban on the sale of all high-calorie drinks and all beverages in containers larger than 8, 10, and 12 ounces in elementary, middle, and high schools, respectively. Several additional recent initiatives to combat childhood obesity have been implemented.

In children, treatment of obesity should focus on healthy eating and increasing physical activity. In general, children should not be put on “diets.” For a child who is overweight, the recommended goal is to maintain weight or slow the rate of weight gain so that weight and BMI gradually decline as the child’s height increases. If the child has already reached his or her anticipated adult weight, maintenance of that weight and prevention of additional gain should be the long-term treatment goal. If the child already exceeds his or her optimal adult weight, the goal of treatment should be a slow weight loss of 10 to 12 pounds per year until this weight is reached. As with adults, increased activity is necessary for successful weight loss or management in children. It is possible to implement these measures successfully mainly within a family unit, and family support to assist the child in weight control and a more healthful lifestyle is necessary. In addition, schools should teach children the basic principles of good nutrition and why eating a balanced diet is important to health.

Overweight and Obese Older Adults

Although obesity is reported in older adults, the numbers are still significantly lower than the levels seen in the young adult population. It is speculated that socioeconomic factors may play a role in this age group when it comes to developing obesity.

Obesity does not appear to make a substantial difference to risks of death among older adults but is a major contributor to increased disability and reduced quality of life in later years. The development of type 2 diabetes mellitus remains a risk. Excess weight reduces the loss of bone mass, and overweight elderly people are less likely to suffer hip fractures, a major cause of morbidity and mortality; health risks of obesity are greater than any advantages.

Pathophysiology

Obesity results from consistent ingestion of more calories than are used for energy, and it substantially increases risks of developing numerous health problems (Box 34.3). Most obesity-related disorders are attributed mainly to the multiple metabolic abnormalities associated with obesity. Abdominal fat out of proportion to total body fat (also called visceral or central obesity), which often occurs in men and postmenopausal women, is considered a greater risk factor for disease and death than lower body obesity. In addition to the many health problems associated with obesity, obesity is increasingly being considered a chronic disease in its own right. Although it has been the focus of much research in recent years, no current theory adequately explains the disorder and its resistance to treatment.

BOX 34.3 Health Risks of Obesity

Obesity is associated with serious health risks. Several disease states and chronic health problems are more prevalent in obese patients, as well as increased mortality. Studies indicate that a high body mass index (BMI) is associated with an increased risk of death from all causes, among both men and women, and in all age groups. In addition, a higher death rate occurs in people who gain weight of 10 kg or more after 18 years of age. Some of the major health risks include the disorders listed below. In general, these conditions tend to worsen as the degree of obesity increases and improve with weight loss.

Cancer

Obesity is associated with a higher prevalence of breast, colon, and endometrial cancers. With breast cancer, risks increase in postmenopausal women with increasing body weight. Women who gain more than 20 pounds from age 18 to midlife have double the risk of breast cancer compared with women who maintain a stable weight during this period of their life. In addition, central obesity apparently increases the risk of breast cancer independent of overall obesity. In women with central obesity, this additional risk factor may be related to an excess of estrogen (from conversion of androstenedione to estradiol in peripheral fatty tissue) and a deficiency of sex hormone-binding globulin to combine with the estrogen.

Colon cancer seems to be more common in obese men and women. In addition, a high BMI may be a risk factor for a higher mortality rate with colon cancer. Endometrial cancer is clearly more common in obese women, with adult weight gain again increasing risk.

Cardiovascular Disorders

Obesity is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disorders and increased mortality from cardiovascular disease. Studies have confirmed the relationship between obesity and increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke in both men and women. In addition, obesity during adolescence is associated with higher rates and greater severity of cardiovascular disease as adults.

Obesity increases risks by aggravating other risk factors such as hypertension, insulin resistance, low HDL cholesterol, and hypertriglyceridemia. In addition, obesity seems to be an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disorders, and central obesity may be more important than BMI as a risk factor for death from cardiovascular disease. The increased mortality rate is seen even with modest excess body weight. Hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and glucose intolerance are known cardiac risk factors that tend to cluster in obese people. Hypertension often occurs in obese people and is thought to play a major role in the increased incidence of cardiovascular disease and stroke observed in patients with obesity. Metabolic abnormalities that occur with obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (e.g., insulin resistance and the resultant hyperinsulinemia) aggravate hypertension and increase cardiovascular risks. The combination of obesity and hypertension is associated with cardiac changes (e.g., thickening of the ventricular wall, ischemia, and increased heart volume) that lead to heart failure more rapidly. Weight loss of as little as 4.5 kg (10 pounds) can decrease blood pressure and cardiovascular risk in many people with obesity and hypertension.

Diabetes Mellitus

Obesity is strongly associated with impaired glucose tolerance, insulin resistance, and diabetes mellitus. In addition, obesity during adolescence is associated with higher rates of diabetes as adults as well as more severe complications of diabetes at younger ages.

The cellular effects by which obesity causes insulin resistance are unknown. Proposed mechanisms include down regulation of insulin receptors, abnormal postreceptor signals, and others. Whatever the mechanism, the impaired insulin response stimulates the pancreatic beta cells to increase insulin secretion, resulting in a relative excess of insulin called hyperinsulinemia, and causes impaired lipid metabolism (increased low-density lipoprotein [LDL] cholesterol and triglycerides and decreased high-density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol). These metabolic changes increase hypertension and other risk factors for cardiovascular disease. As with cardiovascular disease and diabetes in general, central obesity seems to increase the likelihood of serious disease. The abdominal fat of central obesity seems to be more insulin resistant than peripheral fat deposited over the buttocks and legs. Intentional weight loss significantly reduces mortality in obese people with diabetes.

Dyslipidemias

Obesity strongly contributes to abnormal and undesirable changes in lipid metabolism (e.g., increased triglycerides and LDL cholesterol; decreased HDL cholesterol) that increase risks of cardiovascular disease and other health problems.

Gallstones

Obesity apparently increases the risk for developing gallstones by altering production and metabolism of cholesterol and bile. The risk is higher in women, especially those who have had multiple pregnancies or who are taking oral contraceptives. However, rapid weight loss with very-low-calorie diets is also associated with gallstones.

Metabolic Syndrome

Metabolic syndrome is a group of risk factors and chronic conditions that occur together and greatly increase the risks of diabetes mellitus, serious cardiovascular disease, and death. The syndrome is thought to be highly prevalent in the United States. Major characteristics include many of the health problems associated with obesity (e.g., dyslipidemias, hypertension, impaired glucose tolerance, insulin resistance, central obesity). More specifically, metabolic syndrome includes three or more of the following abnormalities:

Central obesity (waist circumference over 40 inches for men and over 35 inches for women)

Central obesity (waist circumference over 40 inches for men and over 35 inches for women)

Serum triglycerides of 150 mg/dL or more

Serum triglycerides of 150 mg/dL or more

HDL cholesterol below 40 mg/dL in men and below 50 mg/dL in women

HDL cholesterol below 40 mg/dL in men and below 50 mg/dL in women

Blood pressure of 135/85 mm Hg or higher

Blood pressure of 135/85 mm Hg or higher

Serum glucose of 110 mg/dL or higher

Serum glucose of 110 mg/dL or higher

Osteoarthritis

Obesity is associated with osteoarthritis (OA) of both weight-bearing joints, such as the hip and knee, and non-weight-bearing joints. Extra weight can stress affected bones and joints, contract muscles that normally stabilize joints, and may alter the metabolism of cartilage, collagen, and bone. In general, obese people develop OA of the knees at an earlier age and are more likely than nonobese people to require knee replacement surgery.

The important role of obesity in OA is supported by the observation that weight loss delays onset and reduces symptoms and disability. Weight reduction may also decrease infection, wound complications, and blood loss if surgery is required. Despite the benefits of weight loss, however, persons with OA have difficulty losing weight because painful joints limit exercise and activity.

Sleep Apnea

Sleep apnea commonly occurs in obese persons. A possible explanation is enlargement of soft tissue in the upper airways that leads to collapse of the upper airways with inspiration during sleep. The obstructed breathing leads to apnea with hypoxemia, hypercarbia, and a stress response. Sleep apnea is associated with increased risks of hypertension, possible right heart failure, and sudden death. Weight loss leads to improvement in sleep apnea.

Miscellaneous Effects

Obesity is associated with numerous difficulties in addition to those described above. These may include

Nownalcoholic fatty liver disease, which is being increasingly recognized and which may lead to liver failure

Nownalcoholic fatty liver disease, which is being increasingly recognized and which may lead to liver failure

Poor wound healing

Poor wound healing

Poor antibody response to hepatitis B vaccine

Poor antibody response to hepatitis B vaccine

A negative perception of people who are obese that affects their education, socioeconomic, and employment status

A negative perception of people who are obese that affects their education, socioeconomic, and employment status

High costs associated with treatment of the medical conditions caused or aggravated by obesity as well as the costs associated with weight loss efforts

High costs associated with treatment of the medical conditions caused or aggravated by obesity as well as the costs associated with weight loss efforts

In women, obesity is associated with menstrual irregularities, difficulty in becoming pregnant, and increased complications of pregnancy (e.g., gestational diabetes, higher rates of labor induction and cesarean section, and increased risk of neural tube and other congenital defects in offspring of obese women).

In women, obesity is associated with menstrual irregularities, difficulty in becoming pregnant, and increased complications of pregnancy (e.g., gestational diabetes, higher rates of labor induction and cesarean section, and increased risk of neural tube and other congenital defects in offspring of obese women).

In men, obesity is associated with infertility.

In men, obesity is associated with infertility.

In children and adolescents, obesity increases risk of bone fractures and muscle and joint pain. Knee pain is commonly reported, and changes in the knee joint make movement and exercise more difficult.

In children and adolescents, obesity increases risk of bone fractures and muscle and joint pain. Knee pain is commonly reported, and changes in the knee joint make movement and exercise more difficult.