Discuss common manifestations of psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the phenothiazines.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the phenothiazines.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the typical antipsychotics.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the typical antipsychotics.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the atypical antipsychotics.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the atypical antipsychotics.

Compare characteristics of the “atypical” antipsychotics with those of the “typical” antipsychotics.

Compare characteristics of the “atypical” antipsychotics with those of the “typical” antipsychotics.

Implement the nursing process in the care of the patient being treated with antipsychotics.

Implement the nursing process in the care of the patient being treated with antipsychotics.

Clinical Application Case Study

Caroline Jones, a 20-year-old college student, is brought to the university’s mental health clinic by a friend. The friend says that Caroline has been talking to the television set and has complained that the voices from the television are telling her that she is ugly. In addition, she has become more withdrawn and reclusive. Caroline has not taken care of her personal hygiene for some time, and she looks disheveled. She receives a diagnosis of psychosis. The treatment plan involves supportive psychotherapy and haloperidol 10 mg twice daily.

KEY TERMS

Akathisia: motor restlessness and inability to be still, usually occurs in the first few months of treatment with antipsychotic agents

Anhedonia: lack of pleasure

Delusions: false beliefs that persist in the absence of reason or evidence

Drug-induced parkinsonism: loss of muscle movement, muscular rigidity and tremors, shuffling gait, masked facies, and drooling

Dystonia: uncoordinated, twisting, and repetitive movements

Extrapyramidal effects: movement disorders such as tardive dyskinesia, akathisia, dystonia, and drug-induced parkinsonism that may occur with usage of antipsychotic drugs

Hallucinations: sensory perceptions of people or objects that are not present in the external environment

Neuroleptics: antipsychotic drugs used to treat disorders that involve thought processes

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a rare but potentially fatal adverse effect; characterized by rigidity, severe hyperthermia, respiratory failure, and acute renal failure

Paranoia: belief that other people control their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors or seek to harm them

Psychosis: severe mental disorder characterized by disorganized thought processes, hallucinations, and delusions

Schizophrenia: variety of related psychotic disorders; symptoms include agitation, behavioral disturbances, delusions, disorganized speech, hallucinations, insomnia, and paranoia

Tardive dyskinesia: irreversible late extrapyramidal effect of some antipsychotic drugs

Introduction

This chapter introduces the pharmacological care of the patient who is experiencing psychosis. Psychosis is a severe mental disorder characterized by disorganized thought processes. Emotional responses may be blunted or inappropriate. Behavior may be bizarre and range from hypoactivity to hyperactivity with agitation, aggressiveness, hostility, and combativeness; it also may involve social withdrawal in which a person pays less-than-normal attention to the environment and other people, deterioration from previous levels of occupational and social functioning (poor self-care and interpersonal skills), hallucinations, and paranoid delusions. This chapter focuses primarily on schizophrenia as a chronic psychosis.

Several features are characteristic of psychosis. Hallucinations are sensory perceptions of people or objects that are not present in the external environment. More specifically, people see, hear, or feel stimuli that are not visible to external observers, and they cannot distinguish between these false perceptions and reality. Hallucinations occur in delirium, dementias, schizophrenia, and other psychotic states. In schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder, they are usually auditory; in delirium, they are usually visual or tactile; and in dementia, they are usually visual. Delusions are false beliefs that persist in the absence of reason or evidence. Deluded people are often fearful and exhibit paranoia; they believe that other people control their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors or seek to harm them. Delusions indicate severe mental illness. Although they are commonly associated with schizophrenia, delusions also occur with delirium, dementias, and other psychotic disorders.

Overview of Psychosis

Psychosis may be acute or chronic. Acute episodes, also called confusion or delirium, have a sudden onset over hours to days and may be precipitated by physical disorders (e.g., brain damage related to cerebrovascular disease or head injury, metabolic disorders, infections); drug intoxication with adrenergics, antidepressants, some anticonvulsants, amphetamines, cocaine, and others; and drug withdrawal after chronic use (e.g., alcohol, benzodiazepine antianxiety or sedative-hypnotic agents). In addition, acute psychotic episodes may be superimposed on chronic dementias and psychoses, such as schizophrenia.

Etiology

Although schizophrenia is often referred to as a single disease, it includes a variety of related disorders. The lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia in the United States is approximately 1%. Males and females are equally affected; however, the disorder manifests itself earlier in males (early 20s for males as compared with late 20s to early 30s for females).

The etiology of schizophrenia is unknown. The neurodevelopmental model proposes that schizophrenia results when abnormal brain synapses are formed in response to an intrauterine insult during the second trimester of pregnancy, when neuronal migration is normally taking place. Intrauterine events such as upper respiratory infection, obstetric complications, and neonatal hypoxia have been associated with schizophrenia. The emergence of psychosis in response to the formation of these abnormal circuits in adolescence or early adulthood corresponds to the time period of neuronal maturation. Some studies of patients with schizophrenia have shown early neurologic abnormalities in infancy and early childhood, such as abnormal movements or motor developmental delays in infancy and psychological abnormalities as early as 4 years of age. This early onset of abnormalities coupled with emergence of schizophrenia in young adulthood suggests a neurodegenerative etiology for schizophrenia as well.

Genetics may play a role in the development of schizophrenia. Family studies identify increased risk if a first degree relative has the illness (10%), if a second degree relative has the illness (3%), if both parents have the illness (40%), and if a monozygotic twin has the illness (48%). Adoption studies of twins suggest that heredity rather than environment is a key factor in the development of schizophrenia.

Many genetic studies are underway to identify the gene or genes responsible for schizophrenia. Possible genes linked to schizophrenia include mutations in WKL1 on chromosome 22, which may play a role in catatonic schizophrenia; mutations in DISC1, which causes delays in migration of brain neurons in mouse models; and mutation in the gene responsible for the glutamate receptor, which regulates the amount of glutamine in synapses.

Pathophysiology

There is evidence of abnormal neurotransmission systems in the brains of people with schizophrenia, especially in the dopaminergic, serotonergic, and glutamatergic systems. There is also evidence of extensive interactions among neurotransmission systems. In addition, illnesses or drugs that alter neurotransmission in one system are likely to alter neurotransmission in other systems. The dopaminergic, serotonergic, and glutamatergic systems have been the focus of the most studies.

Researchers have studied the dopaminergic system more extensively studied than other systems, because, historically, scientists have attributed schizophrenia to increased dopamine activity in the brain. Stimulation of dopamine can initiate psychotic symptoms or exacerbate an existing psychotic disorder. Two findings further support the importance of dopamine: (1) Antipsychotic drugs exert their therapeutic effects by decreasing dopamine activity (i.e., blocking dopamine receptors), and (2) drugs that increase dopamine levels in the brain (e.g., bromocriptine, cocaine, levodopa) can cause signs and symptoms of psychosis.

In addition to the increased amount of dopamine, dopamine receptor subtypes and their location also play a role. In general, authorities believe that overactivity of dopamine2 (D2) receptors in the basal ganglia, hypothalamus, limbic system, brainstem, and medulla accounts for the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, and these experts believe that underactivity of dopamine1 (D1) receptors in the prefrontal cortex accounts for the negative symptoms.

The serotonergic system, which is widespread in the brain, is mainly inhibitory in nature. In schizophrenia, serotonin apparently decreases dopamine activity in the part of the brain associated with negative symptoms, causing or aggravating these symptoms.

The glutamatergic neurotransmission system involves glutamate, the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS). Glutamate receptors are widespread and possibly located on every neuron in the brain. They are also diverse, and their functions may vary according to subtypes and their locations in particular parts of the brain. When glutamate binds to its receptors, the resulting neuronal depolarization activates signaling molecules (e.g., calcium, nitric oxide) within and between brain cells. Thus, glutamatergic transmission may affect every CNS neuron and is considered essential for all mental, sensory, motor, and affective functions. Dysfunction of glutamatergic neurotransmission has been implicated in the development of psychosis.

In addition, the glutamatergic system interacts with the dopaminergic and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) systems and possibly other neurotransmission systems. In people with schizophrenia, evidence indicates the presence of abnormalities in the number, density, composition, and function of glutamate receptors. In addition, glutamate receptors are genetically encoded and can interact with environmental factors (e.g., stress, alcohol and other drugs) during brain development. Thus, glutamatergic dysfunction may account for the roles of genetic and environmental risk factors in the development of schizophrenia as well as the cognitive impairments and negative symptoms associated with the disorder.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms of psychosis may begin gradually or suddenly, usually during adolescence or early adulthood. The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) stipulates that characteristic psychotic symptoms must have been present during a 1-month period with presence of some overt psychotic symptoms for at least 6 months before schizophrenia can be diagnosed. Clinical manifestations of schizophrenia are categorized as positive and negative symptoms. Positive, or excess, symptoms are characterized by CNS stimulation and include agitation, behavioral disturbances, delusions, disorganized speech, hallucinations, insomnia, and paranoia. Negative, or deficit, symptoms are characterized by anhedonia (lack of pleasure), lack of motivation, blunted affect, poor grooming and hygiene, poor social skills, poverty of speech, and social withdrawal. Antipsychotic drugs are generally more effective in treating positive symptoms than negative symptoms.

Drug Therapy

Overall, the goal of drug treatment is to relieve symptoms with minimal or tolerable adverse effects. In patients with acute psychosis, the goal during the first week of treatment is to decrease symptoms (e.g., aggression, agitation, combativeness, hostility) and normalize patterns of sleeping and eating. The next goals may be increased ability for self-care and increased socialization. Therapeutic effects usually occur gradually, over 1 to 2 months. Long-term goals include increasing the patient’s ability to cope with the environment, promoting optimal functioning in self-care and activities of daily living, and preventing acute episodes and hospitalizations. With drug therapy, patients often can participate in psychotherapy, group therapy, or other treatment modalities; return to community settings; and return to their preillness level of functioning.

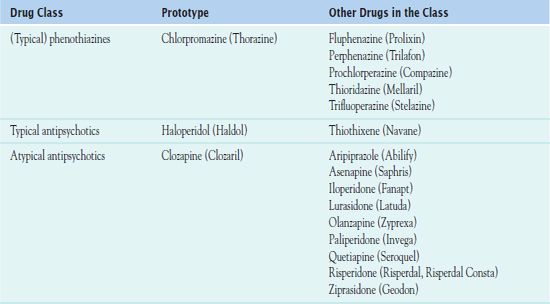

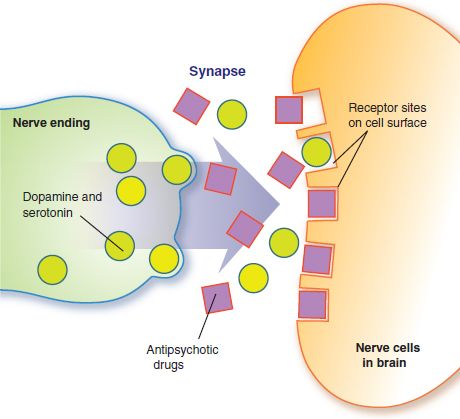

Table 55.1 summarizes the drugs used in the treatment of psychosis, which are also known as neuroleptics. These drugs may be broadly categorized as first-generation or “typical” agents and second-generation or “atypical” agents. First-generation drugs include the phenothiazines and older nonphenothiazines, such as haloperidol. Second-generation drugs or newer nonphenothiazines include clozapine and other related drugs listed in Table 55.1. Most of these drugs bind to D2 dopamine receptors and block the action of dopamine (Fig. 55.1). However, binding to the receptors does not account for antipsychotic effects because binding occurs within a few hours after a drug dose, and antipsychotic effects may not occur until the drugs have been given for a few weeks.

Figure 55.1 Antipsychotic drugs prevent dopamine and serotonin from occupying receptor sites on neuronal cell membranes and exerting their effects on cellular functions. This action leads to changes in receptors and cell functions that account for therapeutic effects (i.e., relief of psychotic symptoms). Other neurotransmitters and receptors may also be involved.

Prescribers caring for patients with psychosis have a greater choice of drugs than ever before. Some general factors to consider include the patient’s age and physical condition, the severity and duration of illness, the frequency and severity of adverse effects produced by each drug, the patient’s use of and response to antipsychotic drugs in the past, the supervision available, and the physician’s experience with a particular drug.

Duration of Treatment

People with schizophrenia usually need to take antipsychotics for years because there is a high rate of relapse (acute psychotic episodes) when drug therapy is discontinued, most often by patients who become unwilling or unable to continue taking their medication. With wider use of maintenance therapy and the newer, better-tolerated antipsychotic drugs, patients may experience fewer psychotic episodes and hospitalizations.

Most antipsychotics are available in oral formulations. Patients who are unable or unwilling to take daily doses of an antipsychotic may receive periodic injections of a long-acting form of fluphenazine, haloperidol, risperidone, or paliperidone. Extrapyramidal symptoms may be more problematic with depot injections of antipsychotics.

Treatment in Children

Schizophrenia in children is often characterized by more severe symptoms and a more chronic course than in adults. Drug therapy in children is largely empiric, because few studies have been conducted in young people. Dosage regulation is difficult because children may require lower plasma levels for therapeutic effects, but they also metabolize antipsychotic drugs more rapidly than adults. It is not clear which antipsychotics are safest and most effective in children and adolescents.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry has established practice guidelines that advocate for high-quality assessment of the child or adolescent with the administration of antipsychotic medications. The purpose of the practice guidelines is to promote the appropriate use of antipsychotic medications and to enhance safety in the pediatric population. Box 55.1 lists major recommendations.

BOX 55.1 Guidelines for the Use of Antipsychotic Medications in Children and Adolescents

Conduct a thorough psychiatric and physical examination before initiating therapy.

Conduct a thorough psychiatric and physical examination before initiating therapy.

Develop a treatment plan based on the best evidence and include strategies for pharmacological and psychosocial treatment.

Develop a treatment plan based on the best evidence and include strategies for pharmacological and psychosocial treatment.

Monitor the patient’s response to treatment both short and long term.

Monitor the patient’s response to treatment both short and long term.

Communicate to the patient and family, educating them about the treatment and monitoring plan.

Communicate to the patient and family, educating them about the treatment and monitoring plan.

Explain all risks and benefits of the treatment plan to the parents.

Explain all risks and benefits of the treatment plan to the parents.

Document the consent of the parents to the treatment plan.

Document the consent of the parents to the treatment plan.

Choose a medication based on potency, adverse effects, and the patient’s medication response.

Choose a medication based on potency, adverse effects, and the patient’s medication response.

Inform the patient and family of the use of medication combinations and the plan for monitoring the response of the medication combination.

Inform the patient and family of the use of medication combinations and the plan for monitoring the response of the medication combination.

From Walkup, J. and the Work Group on Quality Issues. (2009). Practice parameter on the use of psychotropic medication in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(9), 961–973. Retrieved December 22, 2011 from www.jaacap.com. Used with permission from Elsevier.

Drug Use in Home Care

People with chronic mental illness, such as schizophrenia, are among the most challenging in the caseload of the home care nurse. Major recurring problems include failure to take antipsychotic medications as prescribed and the concurrent use of alcohol and other drugs of abuse. Either problem is likely to lead to acute psychotic episodes and hospitalizations. The nurse must assist and support caregivers’ efforts to administer medications and manage adverse effects, other aspects of daily care, and follow-up psychiatric care. In addition, the nurse may need to coordinate the efforts of several health and social service agencies or providers.

Clinical Application 55–1

Describe the positive and negative symptoms that Caroline is experiencing.

Describe the positive and negative symptoms that Caroline is experiencing.

What neurotransmitter system is involved in Caroline’s psychosis?

What neurotransmitter system is involved in Caroline’s psychosis?

How do antipsychotic drugs decrease the Caroline’s psychotic symptoms?

How do antipsychotic drugs decrease the Caroline’s psychotic symptoms?

NCLEX Success

1. A man is diagnosed with schizophrenia. He exhibits anhedonia, which is defined as which of the following?

A. seizure activity

B. lack of pleasure

C. worm-like movements

D. depression

2. A man is hospitalized due to a relapse of his psychotic disorder. He states, “I quit taking my medicines because I always forget to take them at least one time a day.” Which of the following regimens for his antipsychotic medications will increase medication adherence?

A. monthly injections by a home care nurse

B. low-dose daily therapy

C. daily visits to the clinic to receive his medications

D. once-a-week drug therapy

Phenothiazine Antipsychotics

Health care providers have used the phenothiazines to treat psychosis since the 1950s. Although these drugs are historically significant, their usage and clinical importance have waned in recent years.  Chlorpromazine hydrochloride (Thorazine) is the prototype drug of this class.

Chlorpromazine hydrochloride (Thorazine) is the prototype drug of this class.

Pharmacokinetics

Chlorpromazine is well absorbed and distributed to most body tissues, and it reaches high concentrations in the brain. After oral administration, the onset of action is 30 to 60 minutes, with a peak of 2 to 4 hours and a duration of 4 to 6 hours. After intramuscular (IM) administration, the onset of action is 10 to 15 minutes, with a peak at 15 to 20 minutes and a duration of 4 to 6 hours. The half-life is 2 to 30 hours. The drug is metabolized in the liver and excreted in urine.

Action

The mechanism of action of chlorpromazine is not fully understood. When the drug produces antipsychotic effects, it blocks the postsynaptic dopamine receptors in the brain.

Use

The major clinical indication for chlorpromazine and other phenothiazine antipsychotics is schizophrenia. Other uses include treatment of psychotic symptoms associated with brain impairment induced by head injury, tumor, stroke, alcohol withdrawal, overdoses of CNS stimulants, and other disorders.

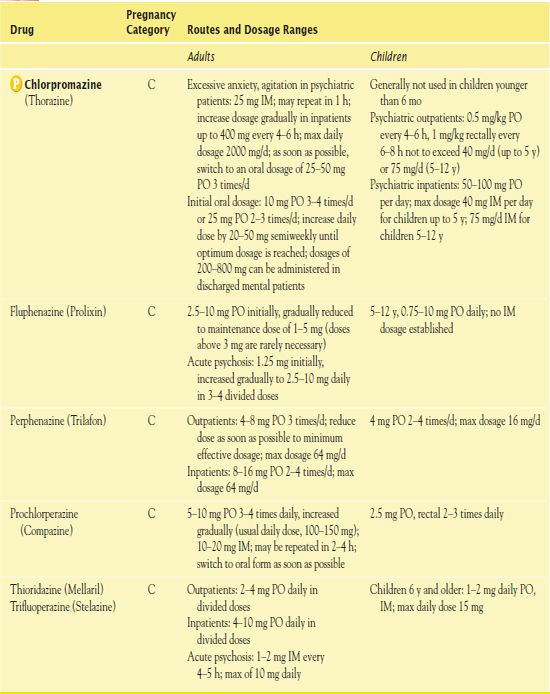

It is necessary to individualize the dosage and route of administration of chlorpromazine according to the patient’s condition and response; in some cases, prescribers may exceed the recommended maximum dosage approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Table 55.2 gives route and dosage information for the phenothiazine antipsychotics.

TABLE 55.2

TABLE 55.2

Use in Older Adults

Chlorpromazine should be administered cautiously to older adults. The dosage of chlorpromazine should be started at one fourth to one third of the level for younger adults. Older adults are more likely to have problems for which chlorpromazine and other antipsychotic agents are contraindicated (e.g., severe cardiovascular disease, liver damage, Parkinson’s disease) or must be used very cautiously (diabetes mellitus, glaucoma, prostatic hypertrophy, peptic ulcer disease, chronic respiratory disorders).

Use in Children

Chlorpromazine is not routinely administered to children under the age of 6 months. Chlorpromazine is administered for the treatment of psychosis. It is also used preoperatively for the control of restlessness and apprehension. Chlorpromazine is administered rectally or intramuscularly for the control of nausea and vomiting.

Use in Patients With Renal Impairment

Excretion of chlorpromazine takes place in the kidneys, and therefore caution is necessary when using the drug in patients with impaired renal function. It is necessary to monitor renal function periodically during long-term therapy and lower the dosage or discontinue the drug altogether if test results (e.g., blood urea nitrogen) become abnormal.

Use in Patients With Hepatic Impairment

Chlorpromazine undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism, which means that caution is warranted in patients with hepatic impairment. In the presence of liver disease (e.g., cirrhosis, hepatitis), metabolism may be slowed and drug elimination half-lives prolonged, with resultant accumulation and increased risk of adverse effects.

Adverse Effects

Chlorpromazine has several adverse effects, including

• CNS effects: excessive sedation, with drowsiness, lethargy, fatigue, slurred speech, impaired mobility, and impaired mental processes. Extrapyramidal effects may also occur. Symptoms include movement disorders such as tardive dyskinesia, akathisia, dystonia, and drug-induced parkinsonism.

• Tardive dyskinesia occurs as the result of long-term chlorpromazine use. Patients may experience lip smacking, tongue protrusion, and facial grimaces and may have choreic movements of trunk and limbs. This condition is usually irreversible, and there is no effective treatment.

• Akathisia, the most common extrapyramidal reaction, may occur about 5 to 60 days from the start of drug therapy.

• Dystonias are uncoordinated bizarre movements of the neck, face, eyes, tongue, trunk, or extremities. These adverse effects may occur suddenly 1 to 5 days after drug therapy is started and may be misinterpreted as seizures or other disorders.

• Drug-induced parkinsonism is loss of muscle movement (akinesia), muscular rigidity and tremors, shuffling gait, masked facies, and drooling.

• Neuroleptic malignant syndrome is a rare but potentially fatal reaction, which may occur hours to months after initial drug use. Symptoms of fever, muscle rigidity, respiratory failure, and confusion develop rapidly.

• Cardiovascular effects: prolonged QT and PR interval, T-wave blunting, and depression of the ST interval

• Hematologic effects: agranulocytosis and pancytopenia

• Other effects: antiadrenergic effects, such as hypotension, dizziness, fatigue, and faintness, as well as respiratory depression; endocrine effects; photosensitivity; and difficulty with temperature regulation

Contraindications

Because of wide-ranging adverse effects, chlorpromazine may cause or aggravate a number of conditions. Contraindications include liver damage, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, parkinsonism, bone marrow depression, severe hypotension or hypertension, coma, and severely depressed states. Caution is warranted in seizure disorders, diabetes mellitus, glaucoma, prostatic hypertrophy, peptic ulcer disease, and chronic respiratory disorders, as well as in pregnancy, especially during the first trimester.

Nursing Implications

Preventing Interactions

Many medications interact with chlorpromazine, increasing or decreasing its effects (Box 55.2). The combination of the herbal supplement with kava results in increased dystonia.

BOX 55.2  Drug Interactions: Chlorpromazine

Drug Interactions: Chlorpromazine