Describe the characteristics of fungi and fungal infections.

Discuss antibacterial drug therapy and immunosuppression as risk factors for development of fungal infections.

Discuss antibacterial drug therapy and immunosuppression as risk factors for development of fungal infections.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for polyenes.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for polyenes.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for azoles.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for azoles.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for echinocandins.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for echinocandins.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the pyrimidine analog.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the pyrimidine analog.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the miscellaneous antifungal agents.

Identify the prototype and describe the action, use, adverse effects, contraindications, and nursing implications for the miscellaneous antifungal agents.

Understand how to implement the nursing process in the care of patients undergoing drug therapy for fungal infections.

Understand how to implement the nursing process in the care of patients undergoing drug therapy for fungal infections.

Clinical Application Case Study

Maria Angelo, age 21, is receiving antibiotic therapy for a strep throat. Following the completion of the course of antibiotics, she begins complaining of vaginal itching. She also notices a cheesy yellow vaginal discharge. Her primary care provider diagnoses Candida albicans vaginal infection and prescribes fluconazole (Diflucan) 150 mg PO, one dose.

KEY TERMS

Candidiasis: infection either containing or caused by Candida fungi

Dermatophytes: fungal parasites that grow in or on the skin

Fungi: plant-like organisms that live as parasites on living tissue or as saprophytes on decaying organic matter

Immunocompromised: having an impaired or weakened immune system

Molds: fungi that are widely dispersed in the environment and either saprophytic or parasitic; multicellular organisms composed of colonies of tangled strands

Mycoses: disease induced by a fungus or resembling such a disease

Yeasts: unicellular fungi of the genus Saccharomyces or Candida

Introduction

This chapter provides an introduction to the pharmacological care of the patient diagnosed with a fungal infection. There are three broad classifications of antifungal agents prescribed in the treatment of fungal infections. The first group discussed is the polyenes, which are administered in the treatment of severe fungal infections. The second group discussed is the azoles, which are the most commonly prescribed antifungal medications. The azoles are administered topically and vaginally. The third group of antifungal agents is the echinocandins, which have fungicidal activity against Candida, including azole-resistant organisms, and fungistatic activity against Aspergillus. This chapter also discusses antifungal agents used in the treatment of dermatophytic infections.

Overview of Fungal Infections

Etiology

Fungi are molds and yeasts that are widely dispersed in the environment and are either saprophytic (i.e., obtaining food from dead organic matter) or parasitic (i.e., obtaining nourishment from living organisms). Molds are multicellular organisms composed of colonies of tangled strands. They form a fuzzy coating on various surfaces (e.g., the mold that forms on spoiled food, the mildew that forms in damp environments). Yeasts are unicellular organisms. Some fungi, called dermatophytes, can grow only at the cooler temperatures of body surfaces. Other fungi, termed dimorphic, can grow as molds outside the body and as yeasts in the warm temperatures of the body. As molds, these fungi produce spores that can persist indefinitely in the environment and can be carried by the wind to distant locations. When these mold spores enter the body, most often by inhalation, they rapidly become yeasts that can invade body tissues. Dimorphic fungi include a number of human pathogens such as those that cause blastomycosis, histoplasmosis, and coccidioidomycosis.

Structurally, fungi are larger and more complex than bacteria. They have a thick, rigid cell wall, of which glucan is one of the components. Glucan is formed by the fungal enzyme, glucan synthetase. Fungi also have a cell membrane composed mainly of ergosterol, a lipid that is similar to cholesterol in human cell membranes. Within the cell membrane, structures are mostly the same as those in human cells (e.g., a nucleus, mitochondria, Golgi apparatus, ribosomes attached to endoplasmic reticulum, a cytoskeleton with microtubules, and filaments).

Fungal infections may be mild and superficial or life-threatening and systemic. Fungi that are pathogenic in humans exist in soil, decaying plants, and other environmental habitats. Some are even part of the endogenous human flora. For example, Candida albicans organisms are part of the normal microbial flora of the skin, mouth, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and vagina. Growth of Candida organisms is normally restrained by intact immune mechanisms and bacterial competition for nutrients. When these restraining forces are altered (e.g., by suppression of the immune system and antibacterial drug therapy), fungal overgrowth and opportunistic infection can occur, leading to the fungal infection called candidiasis. Dermatophytes cause superficial infections of the skin, hair, and nails. They obtain nourishment from keratin, a protein in skin, hair, and nails. Dermatophytic infections include tinea pedis (athlete’s foot) and tinea capitis (ringworm of the scalp) (see Chap. 60).

Systemic or invasive mycoses include the endemic mycoses that can cause disease (e.g., blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, sporotrichosis) in healthy hosts who are exposed to them in the environment and the opportunistic mycoses (e.g., aspergillosis, candidiasis, cryptococcosis) that cause serious infection mainly in immunosuppressed hosts. The fungi that cause endemic mycoses exist as molds in the environment; they grow in soil and decaying organic matter. Infection is acquired by inhalation of airborne spores from contaminated soil. Histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and blastomycosis usually occur as pulmonary disease but may be systemic. These infections often mimic common bacterial infections, and their severity is determined both by the extent of the exposure to the organism and by the immune status of the host. The fungi that cause opportunistic mycoses may be part of the normal body flora (e.g., Candida species) or exist in the environment (Aspergillus, Cryptococcus). Infection occurs after inhalation or inoculation of the fungus into body tissues. Fungi may have characteristics that enhance their ability to cause disease. Cryptococcus neoformans organisms, for example, can become encapsulated, which allows them to evade the normal immune defense mechanism of phagocytosis. Aspergillus organisms produce protease, an enzyme that allows them to destroy structural proteins and penetrate body tissues.

Most fungal infections occur in healthy people but are more severe and invasive in immunocompromised hosts. Serious infections are increasing in incidence, largely because of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections, the use of immunosuppressant drugs to treat patients with cancer or organ transplants, the use of indwelling intravenous (IV) catheters for prolonged drug therapy or parenteral nutrition, implantation of prosthetic devices, and widespread use of broad-spectrum antibacterial drugs.

Pathophysiology and Clinical Manifestations

Pathophysiologic changes associated with fungal infections relate to the causal fungus and the tissue in which it has been colonized. Box 22.1 describes the characteristics of selected fungal infections and associated pathophysiologic changes. This box also identifies the clinical manifestations that result from fungal infection.

BOX 22.1 Selected Fungal Infections

Aspergillosis occurs in debilitated and immunocompromised people, including those with leukemia, lymphoma, or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and those with neutropenia. Invasive aspergillosis is a serious illness characterized by inflammatory granulomatous lesions, which may develop in the bronchi, lungs, ear canal, skin, or mucous membranes of the eye, nose, or urethra. It may extend into blood vessels, which leads to infection of the brain, heart, kidneys, and other organs. It is associated with thrombosis, ischemic infarction of involved tissues, and progressive disease. It is often fatal.

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, an allergic reaction to inhaled Aspergillus spores, may develop in people with asthma and cause bronchoconstriction, wheezing, dyspnea, cough, muscle aches, and fever. The condition is aggravated if the spores germinate and grow in the airways, thereby producing chronic exposure to the antigen and permanent fibrotic damage.

Aspergillus mold is widespread in the environment; spores are released into the air during soil excavations (e.g., for construction of buildings) or handling of decaying plant matter and are carried into most human environments. Spores have been found in water (e.g., hot water faucets, saunas, shower heads, swimming pools), public buildings and private homes (e.g., basements, bedding, humidifiers, ventilation ducts, potted plants, house dust), and foods (e.g., peppers and spices, pasta, peanuts, cashews, coffee beans). In hospitals, sources of infection include contaminated air from building renovations and new construction; hospital water, which may become aerosolized during activities such as patient showering; and cereals, powdered milk, tea, and soy sauce ingested by neutropenic patients. As Aspergillus molds grow, they produce toxins (e.g., aflatoxin, one of the strongest carcinogens known) that contaminate the food chain.

There are several species that cause invasive disease in humans, but Aspergillus fumigatus is the most common. A. fumigatus reproduces by releasing spores, which are small enough to reach the alveoli when inhaled. Most Aspergillus organisms enter the body through the respiratory system, and pulmonary aspergillosis is acquired by inhalation of the spores. Other potential entry sites include damaged skin (e.g., burn wounds, intravenous [IV] catheter insertion sites), operative wounds, the cornea, and the ear.

Blastomycosis occurs with inhalation of spores from a fungus that grows in soil and decaying organic matter. The organism is widespread in the United States. Sporadic cases most often occur in adult males who have extensive exposure to woods and streams with vocational or recreational activities. The infection may be asymptomatic or produce pulmonary symptoms resembling pneumonia, tuberculosis, or lung cancer. It may also be systemic and involve other organs, especially the skin and bone. Skin lesions (e.g., pustules, ulcerations, abscesses) may progress over a period of years and eventually involve large areas of the body. Bone invasion, with arthritis and bone destruction, occurs in 25% to 50% of patients.

Blastomycosis can occur in healthy people with sufficient exposure but is more severe and more likely to involve multiple organs and central nervous system (CNS) disease in immunocompromised patients.

Candidiasis occurs in patients with malignant lymphomas, diabetes mellitus, or AIDS and in patients receiving antibiotic, antineoplastic, corticosteroid, and immunosuppressant drug therapy. Candida organisms are found in soil, on inanimate objects, in hospital environments, and in food. In the human body, they are found on skin and in the gastrointestinal (GI) and genitourinary tracts, including the urine of patients with indwelling bladder catheters. Historically, most infections arose from the normal endogenous organisms of the GI tract and were caused by Candida albicans. In recent years, however, the incidence of infections caused by other candidal strains has greatly increased. Oral, intestinal, vaginal, and systemic candidiasis can occur. Early recognition and treatment of local infections may prevent systemic candidiasis.

Oral candidiasis (thrush) produces painless white plaques on oral and pharyngeal mucosa. It often occurs in newborn infants who become infected during passage through an infected or colonized vagina. In older children and adults, thrush may occur as a complication of diabetes mellitus, as a result of poor oral hygiene, or after taking antibiotics or corticosteroids. It may also occur as an early manifestation of AIDS.

Oral candidiasis (thrush) produces painless white plaques on oral and pharyngeal mucosa. It often occurs in newborn infants who become infected during passage through an infected or colonized vagina. In older children and adults, thrush may occur as a complication of diabetes mellitus, as a result of poor oral hygiene, or after taking antibiotics or corticosteroids. It may also occur as an early manifestation of AIDS.

GI candidiasis often occurs after broad-spectrum antibacterial therapy, which destroys a large part of the normal flora of the intestine. The main symptom is diarrhea.

GI candidiasis often occurs after broad-spectrum antibacterial therapy, which destroys a large part of the normal flora of the intestine. The main symptom is diarrhea.

Vaginal candidiasis occurs in women who are pregnant, have diabetes mellitus, or take oral contraceptives or antibacterial drugs. The main symptom is a yellowish vaginal discharge. The infection may produce inflammation of the perineal area and spread to the buttocks and thighs.

Vaginal candidiasis occurs in women who are pregnant, have diabetes mellitus, or take oral contraceptives or antibacterial drugs. The main symptom is a yellowish vaginal discharge. The infection may produce inflammation of the perineal area and spread to the buttocks and thighs.

Skin candidiasis occurs in people with continuously moist skinfolds or moist surgical dressings. The organism also may cause diaper rash and perineal rashes. Skin lesions are red and macerated.

Skin candidiasis occurs in people with continuously moist skinfolds or moist surgical dressings. The organism also may cause diaper rash and perineal rashes. Skin lesions are red and macerated.

Systemic or invasive candidiasis occurs when the organism gets into the bloodstream and is circulated throughout the body, with the brain, heart, kidneys, and eyes as the most common sites of infection. It occurs as a nosocomial infection in patients with serious illness or who are undergoing drug therapy that suppresses the immune system and may be fatal. Invasive infections may be present in any organ and may produce such disorders as urinary tract infection, endocarditis, and meningitis. It may be diagnosed by positive cultures of blood or tissue. Signs and symptoms depend on the severity of the infection and the organs affected and are indistinguishable from those occurring with bacterial infections.

Systemic or invasive candidiasis occurs when the organism gets into the bloodstream and is circulated throughout the body, with the brain, heart, kidneys, and eyes as the most common sites of infection. It occurs as a nosocomial infection in patients with serious illness or who are undergoing drug therapy that suppresses the immune system and may be fatal. Invasive infections may be present in any organ and may produce such disorders as urinary tract infection, endocarditis, and meningitis. It may be diagnosed by positive cultures of blood or tissue. Signs and symptoms depend on the severity of the infection and the organs affected and are indistinguishable from those occurring with bacterial infections.

The incidence of severe candidal infections has increased in recent years, in part because of increased numbers of neutropenic and immunodeficient patients. In addition, the frequent use of broad-spectrum antibiotics leads to extensive candidal colonization in debilitated patients, and the widespread use of medical devices (e.g., intravascular catheters, monitoring equipment, endotracheal tubes, urinary catheters) allows the organisms to reach sites that are normally sterile. People who use IV drugs also develop invasive candidiasis because the injections inoculate the fungi directly into the bloodstream.

Coccidioidomycosis is caused by an organism that grows as a mold in soil and decaying organic matter and is commonly found in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. Infection results from inhalation of spores that convert to yeasts in the warm environment of the body and often cause asymptomatic or mild respiratory infection. However, the organism may cause acute pulmonary infection with fever, chest pain, cough, headache, and loss of appetite. Radiographs may show small nodules in the lung like those seen in tuberculosis. In some cases, chronic disease develops in which the organisms remain localized and cause large, organism-filled cavities in the lung. These cavities may become fibrotic and require surgical excision. In a few cases, severe, disseminated disease occurs, either soon after the primary infection or after years of chronic pulmonary disease. Disseminated coccidioidomycosis may produce acute or chronic meningitis or a generalized disease with lesions in many internal organs. Skin lesions appear as granulomas that may eventually heal or become ulcerations. Most patients with primary infection recover without treatment; patients with disseminated disease require long-term treatment.

Coccidioidomycosis may occur in healthy or immunocompromised people but is more severe and more likely to become systemic in immunocompromised patients. For example, patients with AIDS who live in endemic areas are highly susceptible to this infection. The severity of the disease also increases with intensity of exposure.

Cryptococcosis is caused by inhalation of spores of Cryptococcus neoformans, an organism found worldwide, especially in bird droppings. The spores have also been found in fruits, vegetables, and dairy products.

When cryptococcosis occurs in healthy people, the primary infection is localized in the lungs, is asymptomatic or produces mild symptoms, and heals without treatment. However, pneumonia may occur and lead to spread of the organisms by the bloodstream. When cryptococcosis occurs in immunocompromised people, it is likely to be more severe and to become disseminated to the CNS, skin, and other organs. People with AIDS are highly susceptible, and cryptococcosis is a frequent opportunistic infection in this population. Infection most often affects the lungs and CNS. Cryptococcal pneumonia in patients with AIDS has a high mortality rate. Cryptococcal meningitis, the most common manifestation of disseminated disease, often produces abscesses in the brain. Clinical manifestations include headache, dizziness, and neck stiffness, and the condition is often mistaken for brain tumor. Later symptoms include coma, respiratory failure, and death if the meningitis is not treated effectively.

Histoplasmosis is a common infection that occurs worldwide, especially in the central and mid-eastern United States. The causative fungus is found in soil and organic debris around chicken houses, bird roosts, and caves inhabited by bats. Exposure to spores may result from activities such as demolishing or remodeling old buildings or cleaning chicken coops. Spores can be picked up by the wind and spread over large areas. Histoplasmosis develops when the spores are inhaled into the lungs, where they rapidly develop into the tissue-invasive yeast cells that reach the bloodstream and become distributed throughout the body. In most cases, the organisms are destroyed or encapsulated by the host’s immune system. The lung lesions heal by fibrosis and calcification and resemble the lesions of tuberculosis. Some people develop histoplasmosis years after the primary infection, probably from reactivation of a latent infection.

Clinical manifestations may vary widely. In people with a normal immune response, manifestations can be correlated with the extent of exposure. Most infections are asymptomatic or produce minimal symptoms for which treatment is not sought. When symptoms occur, they usually resemble an acute, influenza-like respiratory infection and improve within a few weeks. However, people exposed to large amounts of spores may have a high fever and severe pneumonia, which usually resolves with a low mortality rate. Some people, most often adult men with emphysema or other lung diseases, develop chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis with recurrent episodes of cough, fever, and weakness. In addition, histoplasmosis occasionally infects the liver, spleen, and other organs and is rapidly fatal if not treated effectively. The severe, disseminated form usually occurs in patients whose immune system is suppressed by diseases or drugs.

Pneumocystosis is caused by Pneumocystis jiroveci, an organism formerly considered a protozoan but now identified as a fungus. The organism is widespread in the environment, and most people are exposed at an early age. Infections are mild or asymptomatic in immunocompetent people. However, the organism can form cysts in the lungs, persist for long periods, and become activated in immunocompromised hosts. Activation produces an acute, life-threatening pneumonia (pneumocystis pneumonia) characterized by cough, fever, dyspnea, and presence of the organism in sputum. Groups at risk include human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-seropositive people, those receiving corticosteroids or antineoplastics and other immunosuppressive drugs, and caregivers of infected people.

Sporotrichosis occurs when contaminated soil or plant material is inoculated into the skin through small wounds (e.g., thorn pricks) on the fingers, hands, or arms. It is most likely to occur among people who handle sphagnum moss, roses, or baled hay. Thus, infection is a hazard for gardeners and greenhouse workers. It can occur in both healthy and immunocompromised people but is more severe and disseminated in immunocompromised hosts.

Initial lesions, which are usually small, painless bumps resembling insect bites, occur 1 week to 6 months after inoculation. The subcutaneous nodule develops into a necrotic ulcer, which heals slowly as new ulcers appear in adjacent areas. Local lymphatic channels and lymph nodes also develop abscesses, nodules, and ulcers that may persist for years if the disease is not treated effectively. In immunocompromised people, sporotrichosis may spread to various tissues, including the meninges.

Drug Therapy

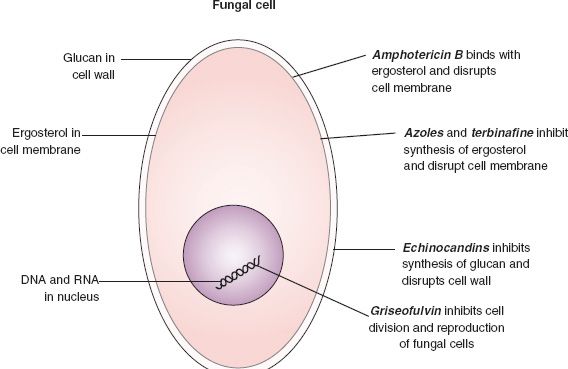

Development of drugs that are effective against fungal cells without being excessively toxic to human cells has been limited because fungal cells are similar to human cells. Most of the available drugs target the fungal cell membrane and produce potentially serious toxicities and drug interactions. In general, antifungal drugs disrupt the structure and function of fungal cell components (Fig. 22.1).

Figure 22.1 Actions of antifungal drugs on fungal cells.

Polyenes (e.g., amphotericin B), azoles (e.g., fluconazole), and the miscellaneous agent griseofulvin act on ergosterol to disrupt the fungal cell membrane. Amphotericin B (and nystatin) binds to ergosterol and forms holes in the membrane, causing leakage of fungal cell contents and lysis of the cell. The azole drugs bind to an enzyme that is required for synthesis of ergosterol. This action causes production of a defective cell membrane, which also allows leakage of intracellular contents and destruction of the cell. Both types of drugs also affect cholesterol in human cell membranes, a characteristic considered mainly responsible for the drugs’ adverse effects.

Echinocandins (e.g., caspofungin) disrupt fungal cell walls rather than fungal cell membranes. They inhibit glucan synthetase, an enzyme required for synthesis of glucan. Glucan is a component of the fungal cell wall; its depletion leads to leakage of cellular contents and cell death. Because human cells do not contain cell walls, these drugs are less toxic than the polyene and azole antifungals.

Drugs for superficial fungal infections of skin and mucous membranes are often applied topically. Numerous preparations are available, many without a prescription. Drugs for systemic infections are given intravenously or orally. Patients with HIV infection or severe neutropenia due to treatment with cytotoxic cancer drugs require aggressive treatment of fungal infections, because they are at high risk for developing life-threatening systemic mycoses. Selected antifungal drugs are further described in the following sections.

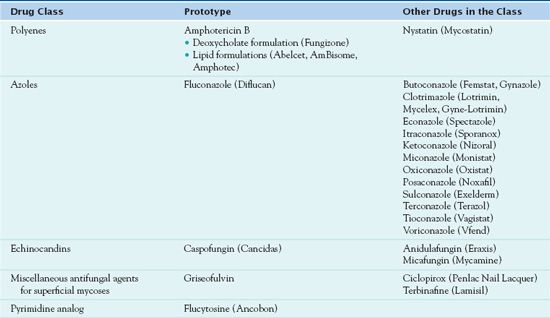

Table 22.1 summarizes the medications used in the treatment of fungal infections.

Clinical Application 22-1

Ms. Angelo is told that she has a Candida infection. What does the nurse tell her about the cause of the fungal infection?

Ms. Angelo is told that she has a Candida infection. What does the nurse tell her about the cause of the fungal infection?

What symptoms does Ms. Angelo experience?

What symptoms does Ms. Angelo experience?

NCLEX Success

1. Which of the following patients is at greatest risk for developing a life-threatening system mycoses?

A. a patient who develops a sexually transmitted disease and is being treated with doxycycline hyclate (Vibramycin)

B. a patient with breast cancer being treated with the chemotherapeutic agent cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan)

C. a patient who is taking warfarin (Coumadin) for the prevention of a thromboemboli

D. a patient with a strep throat who is being treated with cephalexin (Keflex)

2. A 32-year-old construction worker visits the occupational health clinic of the company where he is employed. The man has a high temperature, pain in the right middle and lower lobe of the lung, dyspnea, and malaise. During the admission interview, he states he has been working to restore homes in an urban area with 150-year-old houses. What does the nurse suspect is the cause of his symptoms?

A. pneumocystosis

B. sporotrichosis

C. cryptococcosis

D. histoplasmosis

Polyenes

Amphotericin B, the prototype polyene, is active against most types of pathogenic fungi and is fungicidal or fungistatic, depending on the concentration in body fluids and the susceptibility of the causative fungus. Because of its toxicity, the drug is used only for serious fungal infections. It is usually given for 4 to 12 weeks. There are three additional formulations of amphotericin B. Amphotericin B lipid-based formulations include Abelcet, AmBisome, and Amphotec.

Amphotericin B, the prototype polyene, is active against most types of pathogenic fungi and is fungicidal or fungistatic, depending on the concentration in body fluids and the susceptibility of the causative fungus. Because of its toxicity, the drug is used only for serious fungal infections. It is usually given for 4 to 12 weeks. There are three additional formulations of amphotericin B. Amphotericin B lipid-based formulations include Abelcet, AmBisome, and Amphotec.

Pharmacokinetics

Amphotericin B must be given intravenously for systemic infections. After infusion, the drug is rapidly taken up by the liver and other organs. It is then slowly released back into the bloodstream. Despite its long-term use, little is known about its distribution and metabolic pathways. Drug concentrations in most body fluids are higher in the presence of inflammation; concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are low with or without inflammation. The drug has an initial serum half-life of 24 hours, which represents redistribution from the bloodstream to tissues. This is followed by a second elimination phase, with a half-life of 15 days, which represents elimination from tissue storage sites. Most of the drug is thought to be metabolized in the tissues; some is excreted in the urine and can be detected for several weeks.

Lipid formulations (Abelcet, AmBisome, Amphotec) reach higher concentrations in diseased tissues than in normal tissues, so that larger doses can be given to increase therapeutic effects. At the same time, they cause less damage to normal tissues and decrease adverse effects. These products are much more expensive than the deoxycholate formulation (Fungizone). They are most likely to be used for patients with preexisting renal impairment or conditions in which other nephrotoxic drugs are routinely given (e.g., bone marrow transplant recipients) and when high doses are needed for difficult-to-treat infections. The lipid preparations differ in their characteristics and cannot be used interchangeably.

Action

Amphotericin B binds to the sterols within the fungal cell membrane, resulting in a change in the membrane permeability. This action destroys the fungal cells and prevents them from reproducing. Depending on the concentration of the medication, it has either a fungicidal or fungistatic effect.

Use

Amphotericin B is reserved for patients with progressive and potentially fatal infections resulting from cryptococcosis, North American blastomycosis, systemic candidiasis, disseminated moniliasis, coccidioidomycosis, and histoplasmosis. It is also used for mucormycosis caused by the species of Mucor, Rhizopus, Absidia, Conidiobolus, Basidiobolus; sporotrichosis; and aspergillosis. The drug is also given as an adjunctive agent in the treatment of American mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. A BLACK BOX WARNING ♦ issued by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) states that amphotericin B should be reserved for progressive or potentially fatal infections. It is not recommended for use in noninvasive disease due to the risk of toxicity.

Abelcet is used in the treatment of aspergillosis. Likewise, Amphotec is given to treat aspergillosis if renal toxicity prevents the use of amphotericin B. AmBisome is used in the treatment of cryptococcal meningitis in HIV-infected patients. Patients who are febrile and neutropenic are given AmBisome for presumed fungal infections. Also, AmBisome is administered in the treatment of Aspergillus, Candida, or Cryptococcus when conventional amphotericin is not tolerated (Karch, 2011).

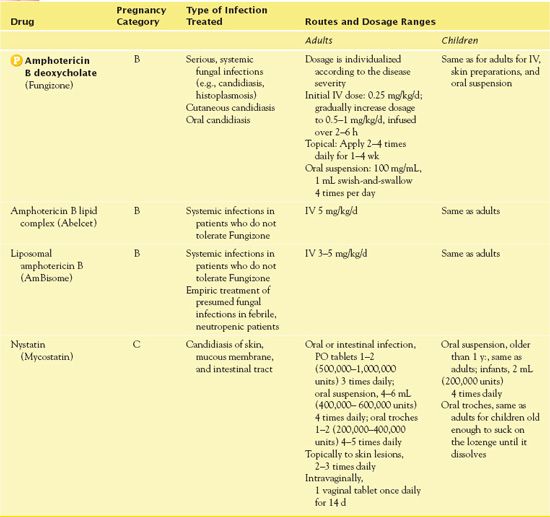

Table 22.2 presents specific information about the use of polyenes, including dosages for adults and children.

TABLE 22.2

TABLE 22.2

Use in Children

Children may take amphotericin B, but such use requires assessment of electrolytes due to magnesium wasting. Health care providers have used the drug successfully to treat children with serious fungal infections, without unusual or severe adverse effects.

Use in Older Adults

Older adults, with the impaired renal and cardiovascular functions that usually accompany aging, are especially vulnerable to serious adverse effects. They require close monitoring to reduce the incidence and severity of nephrotoxicity, hypokalemia, and other adverse drug reactions. Lipid formulations of amphotericin B are less nephrotoxic than the conventional deoxycholate formulation and may be preferred.

Use in Patients With Renal Impairment

Amphotericin B deoxycholate (Fungizone) is nephrotoxic. Renal impairment occurs in most patients (up to 80%) within the first 2 weeks of therapy but usually subsides with dosage reduction or drug discontinuation. Permanent impairment occurs in a few patients. Recommendations to decrease nephrotoxicity include hydrating patients with a liter of 0.9% sodium chloride solution intravenously and monitoring serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) at least weekly. If the patient’s BUN exceeds 40 mg/dL or serum creatinine exceeds 3 mg/dL, the drug should be stopped or dosage should be reduced until renal function recovers. Another strategy is to give a lipid formulation (e.g., Abelcet, AmBisome, Amphotec), which is less nephrotoxic. For patients who already have renal impairment or other risk factors for development of renal impairment, a lipid formulation is indicated. Renal function should still be monitored frequently.

Use in Patients With Hepatic Impairment

Although the main concern with amphotericin B is nephrotoxicity, monitoring of hepatic function during use is recommended.

Use in Patients With Critical Illness

As previously stated, amphotericin B penetrates tissues well, except for the CSF, and only small amounts are excreted in the urine. With prolonged administration, the half-life increases from 1 to 15 days. Hemodialysis does not remove the drug. Lipid formulations may be preferred in critically ill patients because of less nephrotoxicity.

Use in Patients Receiving Home Care

It is important that the home care nurse assess the patient’s immune function with the administration of amphotericin B. The patient’s home should be kept meticulously clean and free of mold-producing substances such as potted plants, fresh flowers, and adhesive nonslip bathtub appliques. The bathroom should be cleaned daily with bleach, and air conditioning and air-filtration systems should be kept clean.

Adverse Effects

Adverse effects of amphotericin B are often severe, with the most serious being multiple organ failure, respiratory arrest, and cardiac arrest. Other adverse affects include:

• GI: nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, (GI) bleeding

• Genitourinary: hypokalemia, azotemia, renal failure

• Hematological: leukopenia, thrombocytopenia