CASE STUDY

Mr. K arrives in the emergency department with chest pain. He is 64 years old, has a history of

hypertension, a significant smoking history (50 pack-years), and is moderately obese. Today, his blood pressure is 160/93, heart rate 100, respiratory rate 24, and oxygen saturation 94%. Per protocol, he receives aspirin, oxygen at 2 L/min via nasal prongs and intravenous morphine. His pain is somewhat relieved by nitroglycerine and morphine, but his EKG shows ST elevations. An emergent

cardiac catheterization shows an 80% stenosis of the left anterior descending artery, and angioplasty is performed with stent placement. Mr. K’s pain subsides quickly after re

perfusion, and he is discharged 2 days later. His discharge medications include propanolol and sublingual nitroglycerine. Mr. K returns to the office for a follow-up 1 week later.

Important Questions to Ask

♦ What are the risk factors for coronary artery disease?

♦ Why does Mr. K’s pain subside after stent placement?

♦ How does propanolol help patients with coronary artery disease?

♦ What teaching will you do regarding the use of sublingual nitroglycerine?

♦ Which cardiovascular risk factors are modifiable, and how will you incorporate these into your teaching with Mr. K?

The functioning of the cardiovascular system is integral to the process of oxygenation. The cardiovascular system perfuses tissues with oxygenated blood and removes the waste products of cellular metabolism. Without a delivery system of blood vessels and a pumping heart, the process of breathing would be useless to the body. The respiratory and cardiovascular systems work together in the process of oxygenation.

There are many disorders of the cardiovascular system, but not all of them are appropriately covered in a book that focuses on oxygenation. This chapter will focus on selected cardiovascular disorders that affect the delivery of oxygen to the cells.

Atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease,

heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, and cardiogenic shock will be covered in this chapter. Cardiovascular disorders require collaborative interventions by members of the healthcare team to facilitate patient

recovery from acute conditions, to minimize complications for patients with chronic conditions, and to maximize the patient’s functional abilities.

ATHEROSCLEROSIS

Atherosclerosis is the most common cause of arterial obstruction and can lead to peripheral arterial disease, coronary artery disease, and cerebrovascular accidents (CVA).

Arteriosclerosis is a general term to describe a number of disorders in which the arterial walls thicken and lose

elasticity. Where

arteriosclerosis is a generalized disorder,

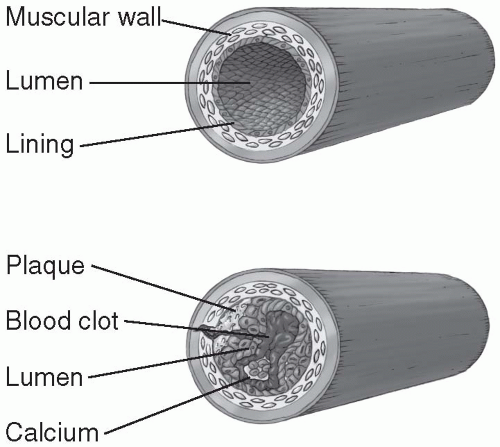

atherosclerosis refers to the thickening of large and medium-size arteries with the deposition of fatty streaks or plaques that decrease the lumen of the artery (see

Figure 7-1).

♦ Accumulation of lipids in the connective tissue

♦ Overgrowth of smooth muscle and accumulation of macrophages and T cells

♦ Formation of a matrix of connective tissue within the intima of the vessel

Atherosclerosis is usually a silent disorder until the blood flow is severely diminished. When the lumen of an artery is obstructed to the point where blood flow is inadequate to meet the tissue demands,

hypoxia and ischemia develop distal to the blockage because of an insufficient supply of oxygen. Without sufficient oxygen, the tissue converts from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism. Lactic acid and other caustic waste products result from anaerobic metabolism, causing irritation and pain in the local tissues. When an artery becomes blocked by plaques, thrombosis, or embolism, tissue necrosis or death may occur.

The etiology of atherosclerotic changes is unknown but many theories exist. One theory is that the intimal (inner) wall of an artery is damaged and platelets cluster or aggregate over the injury (the so-called

platelet aggregation theory). The platelets stimulate proliferation of smooth muscle in the vessel wall, blocking the lumen of the artery. Another theory hypothesizes that lipids deposit over the injury on the intimal wall of the arteries and a fibrous plaque forms over this fatty core (the

chronic endothelial injury theory.) The process of fatty deposition and plaque formation seems to be enhanced by other factors, such as genetic predetermination, diseases such as diabetes and

hypertension, and lifestyle habits such as high fat intake and smoking.

Over years, the atherosclerotic process progresses and the arteries may become narrowed. The tissues distal to the blockage are increasingly deprived of oxygenated blood. Arteries around the heart may become blocked, causing

angina and

myocardial infarction. Arteries in the legs may become narrowed, and nonhealing ulcers or

gangrene may develop on the feet and toes. Infection in the gangrenous tissue may become life-threatening, requiring amputation of the limb. Plaque in the carotid arteries can break off and block cerebral arteries, causing transient ischemic attacks or cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs or strokes.) The ramifications of

atherosclerosis are astounding in terms of loss of function, quality of life, and even death.

Triglycerides, another fatty substance in the blood, are measured separately from cholesterol levels.

Hypertriglyceridemia is an elevation of the triglycerides level above 150 mg/dL and may also be a risk factor for developing

atherosclerosis. Hypertriglyceridemia is thought to be a congenital disorder, and its affect on the development of

atherosclerosis is being studied. Triglycerides may also be elevated with excessive alcohol consumption and disorders of carbohydrate metabolism.

To screen for congenital

dyslipidemia, total serum cholesterol should be performed on all people over the age of 20. The National Cholesterol Education Program (2004) set aggressive guidelines for lowering LDL levels based on a patient’s risk profile, LDL, HDL, and triglyceride levels. Detection of

dyslipidemia in early adulthood allows time for lifestyle changes, dietary modifications, and possibly medications to correct elevations or disproportions in lipoprotein levels (see

Table 7-1).

Atherosclerosis can lead to high blood pressure or

hypertension. The diminished

elasticity of the arteries and the thickening caused by plaque formation and smooth muscle proliferation can make the vessels less responsive to changes in blood pressure. Conversely,

hypertension may cause atherosclerotic changes in the vessel walls because of consistently high pressure and tension exerted on the intimal membranes of the vessels.

Hypertension does not directly decrease oxygen supply to the tissues, but it is a risk factor for the development of

atherosclerosis. Controlling

hypertension is an essential component of preventing atherosclerosic changes to the blood vessels. However, because

hypertension does not directly affect oxygenation, it will not be reviewed in this book.

CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Changes to the

coronary arteries brought on by

atherosclerosis can result in diminished blood flow to the

myocardium. If the heart muscle does not receive an adequate blood supply with the necessary oxygen and nutrients, ischemia can result. Patients with myocardial ischemia often have chest pain or

angina. If the ischemia is prolonged, tissue death occurs and the patient has a

myocardial infarction (MI or heart attack).

Atherosclerotic changes in the

coronary arteries develop silently until the lumen of the artery is blocked more than 70%. At this point, the decrease in blood flow to the myocardial tissue becomes more evident when the patients exercise or increase activity levels, thus increasing the myocardial oxygen demands. The narrowed or obstructed coronary artery can not supply enough blood to meet the myocardial demands, and the result is tissue

hypoxia and ischemia. Patients experience chest pain or tightness that usually subsides once the activity level is decreased and the demand for oxygen subsides.

Angina

When the

myocardium is ischemic, the patient feels chest pain or

angina. The Latin phrase

angina pectoris means “strangling of the chest.” Patients may describe their pain differently. Some common descriptions are tightness, burning, boring, or aching. Careful assessment of symptoms is necessary because women are more apt to describe

angina as indigestion and nausea or vague sensations of not feeling well.

Angina is classified into two groups:

♦ Stable

angina—Chest pain that occurs with exercise and disappears with rest

♦ Unstable

angina—Chest pain at rest or with minimal exertion

Angina is a clinical diagnosis based on a history of chest pain brought on by exertion and relieved by rest. Chest pain relieved by nitroglycerine is also characteristic of

angina. Exercise stress tests and radionuclide scans may be performed to establish the diagnosis. EKG findings may occur during an episode of

angina and disappear after the attack. Coronary arteriography may be used to examine the extent of the coronary artery disease and determine whether other interventions are necessary.

Treatment of Angina

Patients with

angina are at risk for unstable

angina,

myocardial infarction, and sudden death. Treatment involves relieving the symptoms, modifying risk factors, treating underlying coronary artery disease and starting the appropriate medications. Nonpharmacologic treatment is directed at modifying risk factors through weight loss, exercise, and stress reduction. Some ways to reduce stress include lifestyle modification, massage, yoga, and meditation.

Pharmacologic treatment for

angina includes short- and long-acting nitroglycerine, beta-blockers (metoprolol, atenolol, and propanolol), and calcium channel blockers (nifedipine, verapramil, and dilitiazem). Patients are instructed to carry sublingual nitroglycerine with them at all times. Antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin and clopidogrel are used to decrease platelet aggregation. If symptoms persevere despite lifestyle changes, risk reduction and pharmacologic therapies, then surgical intervention (balloon angioplasty or coronary artery bypass surgery) may be required to reperfuse the

myocardium and prevent life-threatening damage to the heart muscle.

Heart Disease

The New York Heart Association (NYHA) has classified heart disease depending on the amount of dysfunction (see

Table 7-2).

Unstable

angina is treated more aggressively because of the increased risk of

myocardial infarction and sudden death. Aspirin and heparin may

be used to prevent MI. Balloon angioplasty and coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) may provide excellent relief if the patient has localized disease and is a good candidate for surgery. (See section on CABG surgery later in this chapter.)

Myocardial Infarction

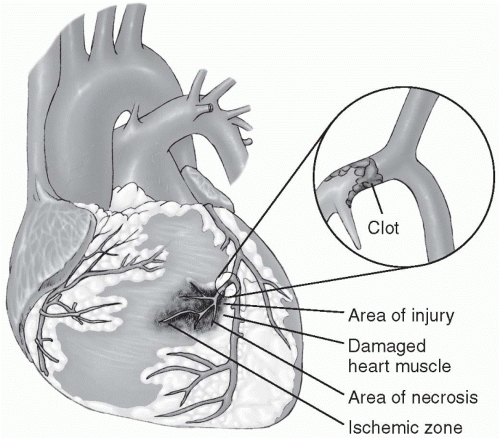

Myocardial infarction is the leading cause of death in the United States with approximately 800,000 people affected annually. Myocardial ischemia can progress to a

myocardial infarction (MI) if a coronary artery is narrowed or occluded for too long. This may happen if a plaque ruptures, blocking a coronary artery, if platelets clump or aggregate on irregular surface (like an atherosclerotic plaque) inside the artery, or if a thrombus develops and occludes the artery. If a coronary artery is 80% to 90% occluded, then ischemia develops in the

myocardium distal to the blockage. If the ischemia continues and the blood flow is not returned, then tissue necrosis or death occurs. This is called a

myocardial infarction.

A

myocardial infarction develops over several hours, and quick treatment may limit the extent of tissue death. Survival rates increase to 90-95% if patients are hospitalized with an MI. The most common cause of death from

myocardial infarctions prior to hospitalization is cardiac

arrest, usually due to ventricular dysrhythmias. Patients with chest pain should be brought into the healthcare system as soon as possible so that life-threatening dysrhythmias can be detected and treated quickly and myocardial oxygenation can be improved.

Myocardial infarctions often begin with necrosis of the subendocardial layer of the heart but may progress through other layers of the

myocardium. If the infarction spreads to all three layers of the heart, this is called a

transmural (“through the wall”) MI. Transmural MIs can affect ventricular wall motion and cardiac output. Left ventricular wall damage from transmural MIs can result in

heart failure and cardiogenic shock.

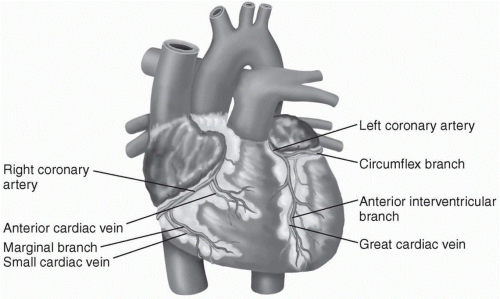

Depending on the location and extent of the tissue death, the conduction system of the heart may be damaged, the cardiac output diminished, or the heart may stop beating. The type of response to an MI depends on which arteries are occluded (see

Figure 7-3).

♦ Left anterior descending (LAD) artery—Supplies anterior wall and septum and usually produces anterior and septal MIs. Anterior wall MIs account for 25% of all infarctions and have the highest mortality rate. The left ventricular wall is frequently damaged in anterior MIs, resulting in ventricular failure and dysrhythmias.

♦ Circumflex artery—Supplies part of the left ventricular wall and portions of the conduction system

♦ Right coronary artery (RCA)—Perfuses the SA and AV nodes, and obstructions of this artery produce bradycardias and heart blocks. Blockage of the RCA usually causes an inferior MI.

Assessment of the Patient with Chest Pain

Assessment of a patient with chest pain who may be having an MI is divided into two parts. One is a quick assessment of the presenting pain. The second part of the assessment includes the family history and risk factors and is done when the patient is stable and comfortable.

The quick assessment is followed by physical assessment and treatment.

Quick Assessment

Rapid assessment of patients with chest pain is important as it provides information to direct interventions to minimize damage to the

myocardium. Quick assessment includes the following:

♦ Type of pain (e.g., burning, aching, stabbing, pressure, or tightness)—Women may describe indigestion or vague sensations of not feeling well.

♦ Location of the pain (e.g., chest, left shoulder, left arm, or jaw should be noted)—Radiation of the pain to the jaw, shoulder, and back is more common during an MI than with

angina.

♦ Intensity of pain—Graded on a scale of 1 to 10

♦ Pain duration—Pain from a

myocardial infarction usually lasts more than 30 minutes and is relieved only by opioids. Chest pain from

angina is usually relieved by nitroglycerine and rest.

♦ Relieving factors—What has the patient tried to relieve the pain and what has worked (e.g., nitroglycerine under the tongue will relieve anginal pain but not MI pain)? Rest may relieve anginal pain but not MI pain.

♦ Precipitating factors—What makes the chest pain come on or become more intense? Anginal pain may be brought on by exertion or stress. MI pain may occur without cause and commonly starts early in the morning.

Patients with chest pain may have additional symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, dizziness, palpitations, shortness of breath, and headache. Note any additional

symptoms that are not necessarily classic chest pain. It is important to remember that women may experience chest pain and describe it differently from men. Women more often report other symptoms that are more general such as indigestion and dizziness, resulting in overlooked cardiac problems. Careful screening questions and an open mind are important in accurately assessing all patients with chest pain.

CASE STUDY

CASE STUDY ATHEROSCLEROSIS

ATHEROSCLEROSIS Arteriosclerosis is a general term to describe a number of disorders in which the arterial walls thicken and lose elasticity.

Arteriosclerosis is a general term to describe a number of disorders in which the arterial walls thicken and lose elasticity. The process of fatty deposition and plaque formation seems to be enhanced by other factors, such as genetic predetermination, diseases such as diabetes and hypertension, and lifestyle habits such as high fat intake and smoking.

The process of fatty deposition and plaque formation seems to be enhanced by other factors, such as genetic predetermination, diseases such as diabetes and hypertension, and lifestyle habits such as high fat intake and smoking. Hypertriglyceridemia is an elevation of the triglycerides level above 150 mg/dL and may also be a risk factor for developing atherosclerosis.

Hypertriglyceridemia is an elevation of the triglycerides level above 150 mg/dL and may also be a risk factor for developing atherosclerosis. To screen for congenital dyslipidemia, total serum cholesterol should be performed on all people over the age of 20.

To screen for congenital dyslipidemia, total serum cholesterol should be performed on all people over the age of 20. CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE Atherosclerotic changes in the coronary arteries develop silently until the lumen of the artery is blocked more than 70%.

Atherosclerotic changes in the coronary arteries develop silently until the lumen of the artery is blocked more than 70%. Careful assessment of symptoms is necessary because women are more apt to describe angina as indigestion and nausea or vague sensations of not feeling well.

Careful assessment of symptoms is necessary because women are more apt to describe angina as indigestion and nausea or vague sensations of not feeling well. Pharmacologic treatment for angina includes short- and long-acting nitroglycerine, beta-blockers (metoprolol, atenolol, and propanolol), and calcium channel blockers (nifedipine, verapramil, and dilitiazem).

Pharmacologic treatment for angina includes short- and long-acting nitroglycerine, beta-blockers (metoprolol, atenolol, and propanolol), and calcium channel blockers (nifedipine, verapramil, and dilitiazem). Myocardial infarction is the leading cause of death in the United States with approximately 800,000 people affected annually.

Myocardial infarction is the leading cause of death in the United States with approximately 800,000 people affected annually. The most common cause of death from myocardial infarctions prior to hospitalization is cardiac arrest, usually due to ventricular dysrhythmias.

The most common cause of death from myocardial infarctions prior to hospitalization is cardiac arrest, usually due to ventricular dysrhythmias. Left ventricular wall damage from transmural MIs can result in heart failure and cardiogenic shock.

Left ventricular wall damage from transmural MIs can result in heart failure and cardiogenic shock.

The myocardium that dies due to the infarction is divided into three sections: the zone of necrosis, surrounded by a zone of injury and, further out, a zone of ischemia.

The myocardium that dies due to the infarction is divided into three sections: the zone of necrosis, surrounded by a zone of injury and, further out, a zone of ischemia.