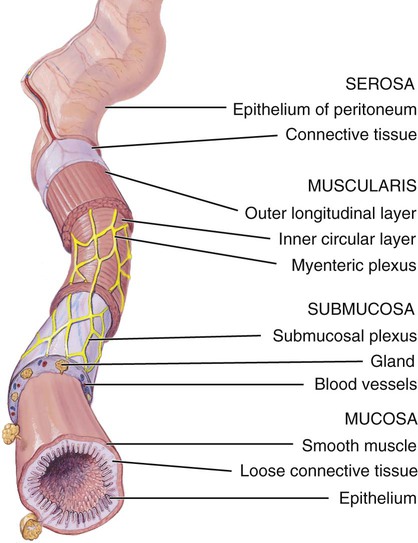

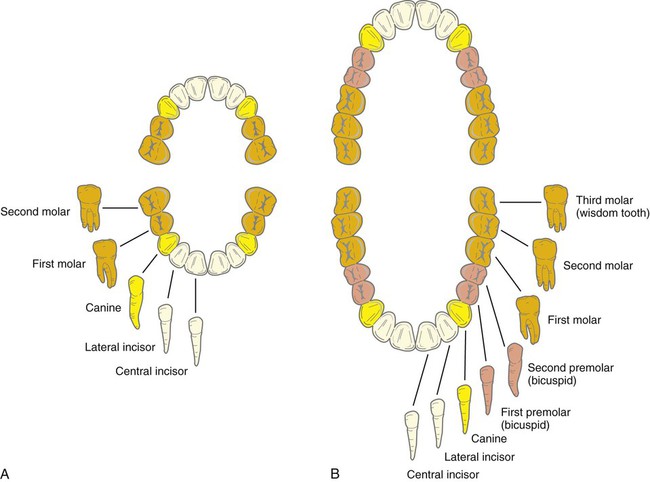

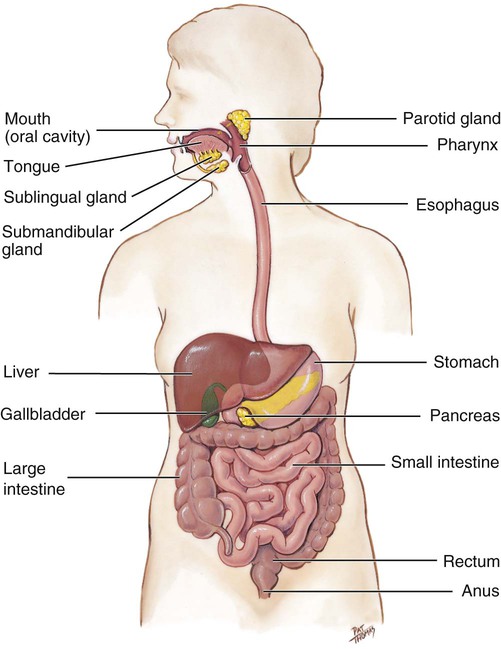

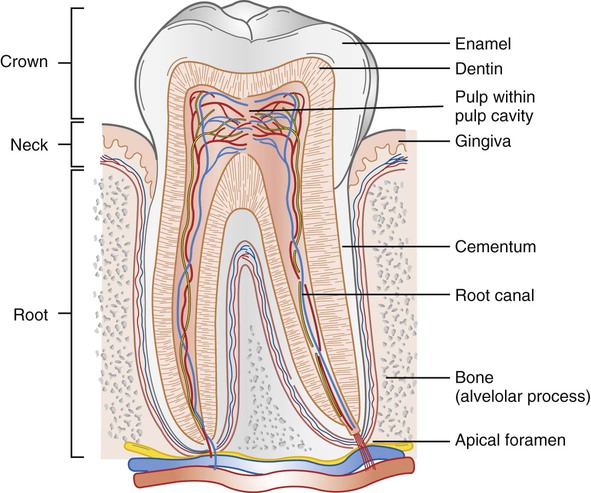

1. Identify the components of the digestive tract and the accessory organs. 2. List six functions of the digestive system. 3. Describe the general histology of the four layers in the digestive tract wall. 4. Describe the features and function of the oral cavity, teeth, pharynx, and esophagus. 5. List and describe the location of the three salivary glands. 6. Explain the function of saliva. 7. Describe the structure and features of the stomach and its role in digestion. 8. Describe the structure and features of the small intestine and its role in digestion and absorption. 9. Describe the structure, features, and function of the large intestine. 10. Describe the structure and function of the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. 11. Explain how substances are absorbed into the body through the small intestine. 12. Describe ways in which the aging of an individual affects the digestive system. The digestive system includes the digestive tract and its accessory organs (Figure 14-1). The function of the digestive system is to process food into molecules that can be absorbed and used by the cells of the body. Food is broken down, bit by bit, until the molecules are small enough to be absorbed and the waste products are eliminated. The digestive tract (also called the alimentary canal or gastrointestinal [GI] tract) consists of a long, continuous tube that extends from the mouth to the anus. It includes the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. The tongue and teeth are accessory structures located in the mouth. The salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas are not part of the digestive tract but are major accessory organs that have a role in digestion. These secrete fluids into the digestive tract. Food undergoes three types of processes in the body: • Ingestion—The first activity of the digestive system is to take in food. This process is called ingestion. Ingestion has to take place before anything else can happen. • Mechanical digestion—The large pieces of food that are ingested have to be broken into smaller particles that can be acted on by various enzymes. This is called mechanical digestion. Mechanical digestion begins in the mouth with chewing, or mastication (mas-tih-KAY-shun), and continues with churning and mixing actions in the stomach. • Chemical digestion—The complex molecules of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats are transformed by chemical digestion into smaller molecules that can be absorbed and used by the cells. Chemical digestion uses water to break down the complex molecules. This process is known as hydrolysis. Digestive enzymes speed up the hydrolysis process, which is otherwise slow. • Movements—After ingestion and mastication, the food particles move from the mouth into the pharynx, and then into the esophagus. This movement is called deglutition (dee-gloo-TISH-un), or swallowing. Mixing movements occur in the stomach as a result of smooth muscle contraction. These repetitive contractions mix the food particles with enzymes and other fluids. The movements that propel the food particles through the digestive tract are called peristalsis. These are rhythmic waves of contractions that move the food particles through the various regions in which mechanical and chemical digestion takes place. • Absorption—The simple molecules that are produced from chemical digestion pass through the lining of the small intestine into the blood. This process is called absorption. • Elimination—The food molecules that cannot be digested need to be eliminated from the body. The removal of indigestible wastes through the anus, in the form of feces, is defecation (def-eh-KAY-shun). The wall of the digestive tract has four layers or tunics (Figure 14-2): The muscular layer (labeled muscularis in Figure 14-2) consists of two layers of smooth muscle. The inner circular layer has fibers arranged in a circular manner around the circumference of the tube. When these muscles contract, the diameter of the tube is decreased. In the outer longitudinal layer the fibers run lengthwise along the long axis of the tube. When these fibers contract, their length decreases and the tube shortens. A network of autonomic nerve fibers, called the myenteric (mye-en-TAIR-ik) plexus, exists between the circular and longitudinal muscle layers. The myenteric plexus, along with the submucosal plexus, is important for controlling the movements and secretions of the digestive tract. In general, parasympathetic impulses stimulate movement and secretion in the GI tract and sympathetic impulses inhibit these activities. The largest and most movable organ in the oral cavity is the tongue. Most of the tongue consists of skeletal muscle. The major attachment for the tongue is the posterior region, or root, which is anchored to the hyoid bone. The anterior portion is relatively free but is connected to the floor of the mouth, in the midline, by a membranous fold of tissue called the lingual frenulum. The dorsal surface of the tongue is covered by tiny projections called papillae. The papillae provide friction for manipulating food in the mouth, and they also contain the taste buds (see Chapter 10). The lingual tonsils are embedded in the posterior surface of the tongue. The lingual tonsils provide defense against bacteria that enter the mouth. Two different sets of teeth develop in the mouth. The first set begins to appear at approximately 6 months of age and continues to develop until about Different teeth are shaped to handle food in different ways. The incisors are chisel-shaped and have sharp edges for biting food. Cuspids (canines) are cone-shaped and have points for grasping and tearing food. Bicuspids (premolars) and molars have flat surfaces with rounded projections for crushing and grinding. Note the location of each type of tooth in Figure 14-3. Although the different types of teeth have different shapes, each tooth has three parts: The central core of a tooth is the pulp cavity. It contains the pulp, which consists of connective tissue, blood vessels, and nerves. In the root, the pulp cavity is called the root canal. Nerves and blood vessels enter the root through an apical foramen. The pulp cavity is surrounded by dentin, which forms the bulk of the tooth. Dentin is a living cellular substance similar to bone. In the root, the dentin is surrounded by a thin layer of calcified connective tissue called cementum, which attaches the root to the periodontal ligaments. The ligaments have fibers that firmly anchor the root in the alveolar process. Enamel surrounds the dentin in the crown of the tooth. Enamel is the hardest substance in the body. Figure 14-4 shows a longitudinal section of a tooth and illustrates the major features.

Digestive System

Introduction to the Digestive System

Functions of the Digestive System

General Structure of the Digestive Tract

Muscular Layer

Components of the Digestive Tract

Mouth

Tongue

Teeth

years of age. This set is known as the primary or deciduous teeth. The primary teeth contain 10 teeth in each jaw for a total of 20 teeth. Figure 14-3, A illustrates the types of primary teeth. Starting at 6 years of age, the primary teeth begin to fall out and are replaced by the secondary or permanent teeth. This set contains 16 teeth in each jaw for a total of 32 teeth. These teeth are illustrated in Figure 14-3, B.

years of age. This set is known as the primary or deciduous teeth. The primary teeth contain 10 teeth in each jaw for a total of 20 teeth. Figure 14-3, A illustrates the types of primary teeth. Starting at 6 years of age, the primary teeth begin to fall out and are replaced by the secondary or permanent teeth. This set contains 16 teeth in each jaw for a total of 32 teeth. These teeth are illustrated in Figure 14-3, B.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Digestive System

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access