On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe major trends in growth and development. • Explain the alterations in the major body systems that take place during the process of growth and development. • Discuss the development and relationships of personality, cognition, language, morality, spirituality, and self-concept. • Describe the role of play in the growth and development of children. • Demonstrate an understanding of the role of innate and environmental factors in the physical and emotional development of children. • Growth—Increase in number and size of cells as they divide and synthesize new proteins; results in increased size and weight of the whole or any of its parts • Development—Gradual change and expansion; advancement from lower to more advanced stages of complexity; the emerging and expanding of the individual’s capacities through growth, maturation, and learning • Maturation—Increase in competence and adaptability; aging; usually used to describe a qualitative change; a change in the complexity of a structure that makes it possible for that structure to begin functioning; to function at a higher level • Differentiation—Processes by which early cells and structures are systematically modified and altered to achieve specific and characteristic physical and chemical properties; sometimes used to describe the trend of mass to specific; development from simple to more complex activities and functions All of these processes are interrelated, simultaneous, and ongoing; none occurs apart from the others. The processes depend on a sequence of endocrine, genetic, constitutional, environmental, and nutritional influences (Seidel, Ball, Dains, et al., 2007). The child’s body becomes larger and more complex; the personality simultaneously expands in scope and complexity. Very simply, growth can be viewed as a quantitative change, and development as a qualitative change. Most authorities in the field of child development conveniently categorize child growth and behavior into approximate age stages or in terms that describe the features of a developmental age period. The age ranges of these stages admittedly are arbitrary and, because they do not take into account individual differences, cannot be applied to all children with any degree of precision. However, categorization affords a convenient means to describe the characteristics associated with the majority of children at periods when distinctive developmental changes appear and specific developmental tasks must be accomplished. (A developmental task is a set of skills and competencies peculiar to each developmental stage that children must accomplish or master to deal effectively with their environment.) It is also significant for nurses to know that there are characteristic health problems peculiar to each major phase of development. The sequence of descriptive age periods and subperiods that are used here and elaborated on in subsequent chapters is listed in Box 28-1. Growth and development proceed in regular, related directions or gradients and reflect the physical development and maturation of neuromuscular functions (Fig. 28-1). The first pattern is the cephalocaudal, or head-to-tail, direction. The head end of the organism develops first and is large and complex; the lower end is small and simple and takes shape at a later period. The physical evidence of this trend is most apparent during the period before birth, but it also applies to postnatal behavior development. Infants achieve structural control of their heads before they have control of their trunks and extremities, hold their backs erect before they stand, use their eyes before their hands, and gain control of their hands before they have control of their feet. As children grow their external dimensions change. These changes are accompanied by corresponding alterations in structure and function of internal organs and tissues that reflect the gradual acquisition of physiologic competence. Each part has its own rate of growth, which may be directly related to alterations in the size of the child (e.g., the heart rate). Skeletal muscle growth approximates whole body growth; brain, lymphoid, adrenal, and reproductive tissues follow distinct and individual patterns (Fig. 28-2). When growth deficiency has a secondary cause such as severe illness or acute malnutrition, recovery from the illness or the establishment of an adequate diet produces a dramatic acceleration of the growth rate that usually continues until the child’s individual growth pattern is resumed. The most prominent feature of childhood and adolescence is physical growth (Fig. 28-3). Throughout development various tissues in the body undergo changes in growth, composition, and structure. In some tissues the changes are continuous (e.g., bone growth and dentition); in others significant alterations occur at specific stages (e.g., appearance of secondary sex characteristics). When these measurements are compared with standardized norms, a child’s developmental progress can be determined with a high degree of confidence (Table 28-1). Growth in children with Down syndrome differs from that in other children. They have slower growth velocity between 6 months and 3 years and then again in adolescence. Puberty occurs earlier, and they achieve shorter stature. This population of patients is frequent users of the health care system, often with multiple providers, and benefit from the use of the Down syndrome growth chart to monitor their growth (Cronk, Crocker, Pueschel, et al., 1988; Myrelid, Gustafsson, Ollars, et al., 2002). TABLE 28-1 GENERAL TRENDS IN HEIGHT AND WEIGHT GAIN DURING CHILDHOOD *Annual height and weight gains for each age-group represent averaged estimates from a variety of sources. †Jung FE, Czajka-Narins DM: Birth weight doubling and tripling times: an updated look at the effects of birth weight, sex, race, and type of feeding, Am J Clin Nutr 42:182–189, 1985. Both bone age determinants and state of dentition are used as indicators of development. Because both are discussed elsewhere, neither is elaborated here (see next section for bone age; see also Chapter 31 for dentition). Nurses must understand that the growing bones of children possess many unique characteristics. Bone fractures occurring at the growth plate may be difficult to discover and may significantly affect subsequent growth and development (Urbanski and Hanlon, 1996). Factors that may influence skeletal muscle injury rates and types in children and adolescents include (Caine, DiFiori, and Maffulli, 2006; Kaczander, 1997): • Less protective sports equipment for children. • Less emphasis on conditioning, especially flexibility. • In adolescents, fractures are more common than ligamentous ruptures because of the rapid growth rate of the physeal (segment of tubular bone that is concerned mainly with growth) zone of hypertrophy. Physiologic changes that take place in all organs and systems are discussed as they relate to dysfunction. Other changes such as pulse and respiratory rates and blood pressure are an integral part of physical assessment (see Chapter 29). In addition, there are changes in basic functions, including metabolism, temperature, and patterns of sleep and rest. Body temperature, reflecting metabolism, decreases over the course of development (see Appendix C). Thermoregulation is one of the most important adaptation responses of infants during the transition from intrauterine to extrauterine life. In healthy neonates hypothermia can result in several negative metabolic consequences such as hypoglycemia, elevated bilirubin levels, and metabolic acidosis. Skin-to-skin care, also referred to as kangaroo care, is an effective way to prevent neonatal hypothermia in infants. Unclothed, diapered infants are placed on the parent’s bare chest after birth, promoting thermoregulation and attachment (Galligan, 2006). After the unstable regulatory ability in the neonatal period, heat production steadily declines as the infant grows into childhood. Individual differences of 0.5° to 1° F are normal, and occasionally a child normally displays an unusually high or low temperature. Beginning at approximately 12 years of age, girls display a temperature that remains relatively stable, but the temperature in boys continues to fall for a few more years. Females maintain a temperature slightly above that of males throughout life. Newborn infants sleep much of the time that is not occupied with feeding and other aspects of their care. As they grow older, the total time spent in sleep gradually decreases, they remain awake for longer periods, and they sleep longer at night. For example, the length of a sleep cycle increases from approximately 50 to 60 minutes in newborn infants to approximately 90 minutes in adolescents (Anders, Sadeh, and Appareddy, 2005). During the latter part of the first year, most children sleep through the night and take one or two naps during the day. By the time they are 12 to 18 months old, most children have eliminated the second nap. After age 3 years children have usually given up daytime naps except in cultures in which an afternoon nap or siesta is customary. Sleep time declines slightly from ages 4 to 10 years and increases somewhat during the pubertal growth spurt. Growth is uneven during the periods of childhood between infancy and adolescence, when there are plateaus and small growth spurts. Children’s appetites fluctuate in response to these variations until the turbulent growth spurt of adolescence, when adequate nutrition is extremely important but may be subjected to numerous emotional influences. Adequate nutrition is closely related to good health throughout life, and an overall improvement in nourishment is evidenced by the gradual increase in size and early maturation of children in this century (see Community Focus box). Temperament is defined as “the manner of thinking, behaving, or reacting characteristic of an individual” (Chess and Thomas, 1999) and refers to the way in which a person deals with life. From the time of birth children exhibit marked individual differences in the way they respond to their environment and the way others, particularly the parents, respond to them and their needs. A genetic basis has been suggested for some differences in temperament. Nine characteristics of temperament have been identified through interviews with parents (Box 28-2). Temperament refers to behavioral tendencies, not to discrete behavioral acts. There are no implications of good or bad. Most children can be placed into one of three common categories based on their overall pattern of temperamental attributes: • The easy child—Easygoing children are even tempered, are regular and predictable in their habits, and have a positive approach to new stimuli. They are open and adaptable to change and display a mild-to–moderately intense mood that is typically positive. Approximately 40% of children fall into this category. • The difficult child—Difficult children are highly active, irritable, and irregular in their habits. Negative withdrawal responses are typical, and they require a more structured environment. These children adapt slowly to new routines, people, and situations. Mood expressions are usually intense and primarily negative. They exhibit frequent periods of crying, and frustration often produces violent tantrums. This group represents about 10% of children. • The slow-to-warm-up child—Slow-to-warm-up children typically react negatively and with mild intensity to new stimuli and, unless pressured, adapt slowly with repeated contact. They respond with only mild but passive resistance to novelty or changes in routine. They are inactive and moody but show only moderate irregularity in functions. Fifteen percent of children demonstrate this temperament pattern. Thirty-five percent of children either have some, but not all, of the characteristics of one of the categories or are inconsistent in their behavioral responses. Many normal children demonstrate this wide range of behavioral patterns. Observations indicate that children who display the difficult or slow-to-warm-up patterns of behavior are more vulnerable to the development of behavior problems in early and middle childhood. Any child can develop behavior problems if there is dissonance between his or her temperament and the environment. Demands for change and adaptation that are in conflict with the child’s capacities can become excessively stressful. However, authorities emphasize that it is not the temperament patterns of children that place them at risk; rather it is the degree of fit between children and their environment, specifically their parents, that determines the degree of vulnerability. The potential for optimum development exists when environmental expectations and demands fit with the individual’s style of behavior and the parents’ ability to navigate this period (Chess and Thomas, 1999). Research indicates that irritable and unadaptable infants can raise doubts in mothers about their competence (Beck, 1996). Additional research indicates that a child’s temperament can affect parent-child interactions and influence the parents’ self-esteem, marital harmony, mood, and overall satisfaction as parents (Carey, 1998). Studies on the relationship between temperament and the ability to perform a task successfully (mastery motivation) have found that infants with high mastery are more cooperative and less difficult (Morrow and Camp, 1996). Principles that can be used by nurses in direct patient care and providing anticipatory guidance are listed in Box 28-3. Personality and cognitive skills develop in much the same manner as biologic growth—new accomplishments build on previously mastered skills. Many aspects depend on physical growth and maturation. This is not a comprehensive account of the multiple facets of personality and behavior development. Many aspects are integrated with the child’s emotional and social development in a later discussion of various age-groups. Table 28-2 summarizes some of the developmental theories. TABLE 28-2 SUMMARY OF PERSONALITY, COGNITIVE, AND MORAL DEVELOPMENT THEORIES According to Freud all human behavior is energized by psychodynamic forces, and this psychic energy is divided among three components of personality: the id, ego, and superego (Freud, 1933). The id, the unconscious mind, is the inborn component that is driven by instincts. It obeys the pleasure principle of immediate gratification of needs, regardless of whether the object or action can actually do so. The ego, the conscious mind, serves the reality principle. It functions as the conscious or controlling self that is able to find realistic means for gratifying the instincts while blocking the irrational thinking of the id. The superego, the conscience, functions as the moral arbitrator and represents the ideal. It is the mechanism that prevents individuals from expressing undesirable instincts that might threaten the social order. Freud considered the sexual instincts to be significant in the development of the personality (Freud, 1964). However, he used the term psychosexual to describe any sensual pleasure. During childhood certain regions of the body assume a prominent psychologic significance as the source of new pleasures and conflicts gradually shifts from one part of the body to another at particular stages of development: • Oral stage (birth to 1 year)—During infancy the major source of pleasure seeking is centered on oral activities such as sucking, biting, chewing, and vocalizing. Children may prefer one of these over the others, and the preferred method of oral gratification can provide some indication of the personality they develop. • Anal stage (1 to 3 years)—Interest during the second year of life centers in the anal region as sphincter muscles develop and children are able to withhold or expel fecal material at will. At this stage the climate surrounding toilet training can have lasting effects on children’s personalities. • Phallic stage (3 to 6 years)—During the phallic stage the genitalia become an interesting and sensitive area of the body. Children recognize differences between the sexes and become curious about the dissimilarities. This is the period around which the controversial issues of the Oedipus and Electra complexes, penis envy, and castration anxiety are centered. • Latency period (6 to 12 years)—During the latency period children elaborate on previously acquired traits and skills. Physical and psychic energy is channeled into acquisition of knowledge and vigorous play. • Genital stage (age 12 years and older)—The last significant stage begins at puberty with maturation of the reproductive system and production of sex hormones. The genital organs become the major source of sexual tensions and pleasures, but energies are also invested in forming friendships and preparing for marriage.

Developmental and Genetic Influences on Child Health Promotion

Growth and Development

Foundations of Growth and Development

Stages of Development

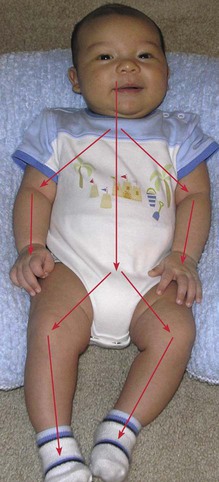

Patterns of Growth and Development

Directional Trends.

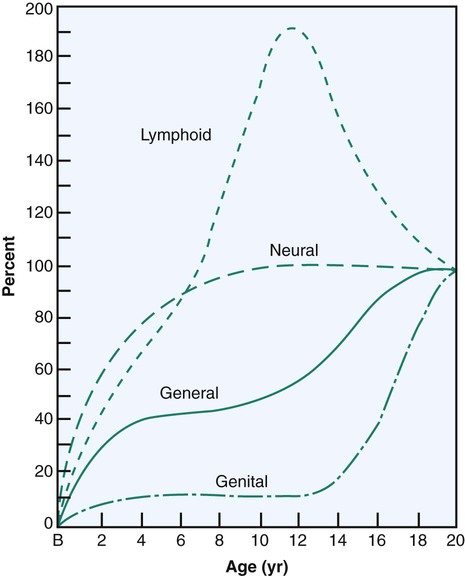

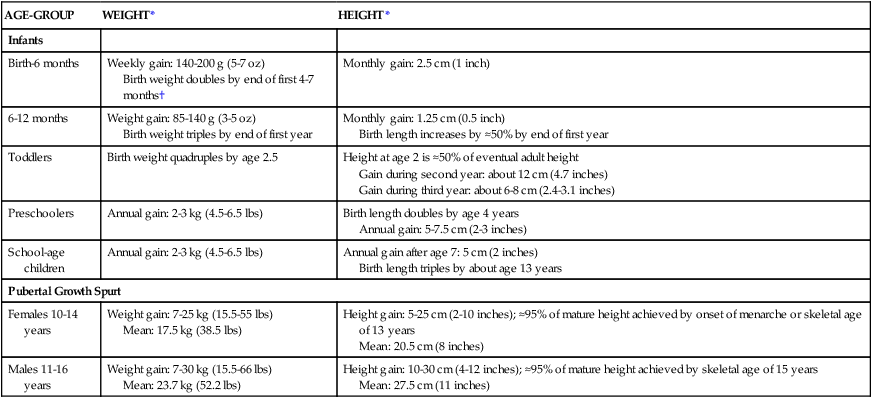

Biologic Growth and Physical Development

Biologic Determinants of Growth and Development

AGE-GROUP

WEIGHT*

HEIGHT*

Infants

Birth-6 months

Weekly gain: 140-200 g (5-7 oz)

Birth weight doubles by end of first 4-7 months†

Monthly gain: 2.5 cm (1 inch)

6-12 months

Weight gain: 85-140 g (3-5 oz)

Birth weight triples by end of first year

Monthly gain: 1.25 cm (0.5 inch)

Birth length increases by ≈50% by end of first year

Toddlers

Birth weight quadruples by age 2.5

Height at age 2 is ≈50% of eventual adult height

Gain during second year: about 12 cm (4.7 inches)

Gain during third year: about 6-8 cm (2.4-3.1 inches)

Preschoolers

Annual gain: 2-3 kg (4.5-6.5 lbs)

Birth length doubles by age 4 years

Annual gain: 5-7.5 cm (2-3 inches)

School-age children

Annual gain: 2-3 kg (4.5-6.5 lbs)

Annual gain after age 7: 5 cm (2 inches)

Birth length triples by about age 13 years

Pubertal Growth Spurt

Females 10-14 years

Weight gain: 7-25 kg (15.5-55 lbs)

Mean: 17.5 kg (38.5 lbs)

Height gain: 5-25 cm (2-10 inches); ≈95% of mature height achieved by onset of menarche or skeletal age of 13 years

Mean: 20.5 cm (8 inches)

Males 11-16 years

Weight gain: 7-30 kg (15.5-66 lbs)

Mean: 23.7 kg (52.2 lbs)

Height gain: 10-30 cm (4-12 inches); ≈95% of mature height achieved by skeletal age of 15 years

Mean: 27.5 cm (11 inches)

Skeletal Growth and Maturation

Physiologic Changes

Temperature

Sleep and Rest

Nutrition

Temperament

Significance of Temperament

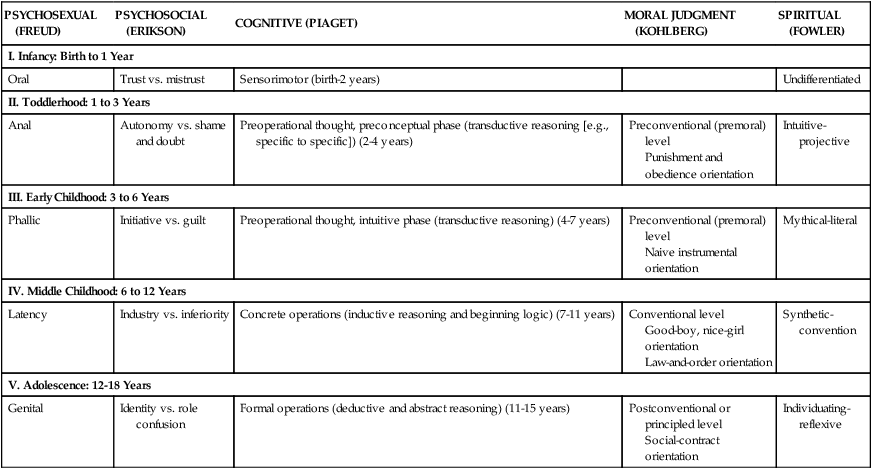

Development of Personality and Mental Function

PSYCHOSEXUAL (FREUD)

PSYCHOSOCIAL (ERIKSON)

COGNITIVE (PIAGET)

MORAL JUDGMENT (KOHLBERG)

SPIRITUAL (FOWLER)

I. Infancy: Birth to 1 Year

Oral

Trust vs. mistrust

Sensorimotor (birth-2 years)

Undifferentiated

II. Toddlerhood: 1 to 3 Years

Anal

Autonomy vs. shame and doubt

Preoperational thought, preconceptual phase (transductive reasoning [e.g., specific to specific]) (2-4 years)

Preconventional (premoral) level

Punishment and obedience orientation

Intuitive-projective

III. Early Childhood: 3 to 6 Years

Phallic

Initiative vs. guilt

Preoperational thought, intuitive phase (transductive reasoning) (4-7 years)

Preconventional (premoral) level

Naive instrumental orientation

Mythical-literal

IV. Middle Childhood: 6 to 12 Years

Latency

Industry vs. inferiority

Concrete operations (inductive reasoning and beginning logic) (7-11 years)

Conventional level

Good-boy, nice-girl orientation

Law-and-order orientation

Synthetic-convention

V. Adolescence: 12-18 Years

Genital

Identity vs. role confusion

Formal operations (deductive and abstract reasoning) (11-15 years)

Postconventional or principled level

Social-contract orientation

Individuating-reflexive

Theoretic Foundations of Personality Development

Psychosexual Development (Freud)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Developmental and Genetic Influences on Child Health Promotion

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access