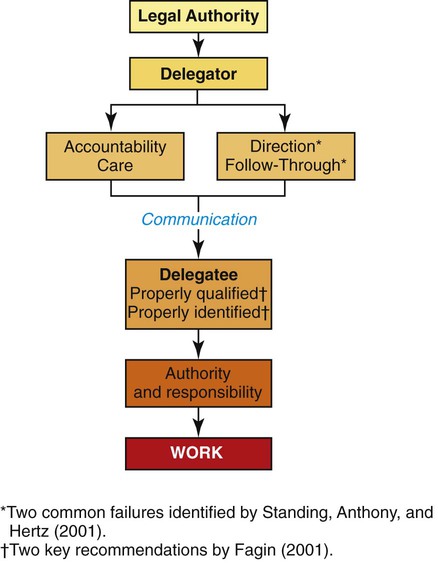

• Define delegation and its component parts. • Evaluate how tasks and relationships influence delegation to a specific individual. • Comprehend the legal authority for a registered nurse to delegate. • Value the complexity of decision making related to delegation. In the mid-1990s, a dramatic shift from primary nursing (an all-professional staff concept) to a multilevel nursing staff occurred. As a result, addressing the topic of delegation in some detail became critical to safe care. This return, however, was not to delegation as it was known earlier. In part, the difference today is based on the sophisticated demand for cost containment and reduction and the new complexities that are present in health care. As the healthcare industry emphasizes community-based care, the challenge of delegation and the resultant supervision become even more difficult. The increase, especially in UNPs, related in the past to a shortage of nurses. An even more dramatic one is predicted over the next several years, rising to a predicted need of 500,000 more RNs by 2025 (Buerhaus, 2009). Therefore, in addition to the supply of nurses and healthcare cost-control measures, the role of the RN will change to meet the increasing demands for care. Nursing’s flexibility to alter how we function based on the changes we find has allowed nursing to survive and sometimes thrive. The consistent element, irrespective of how we function, is care. During the early part of the twenty-first century, both the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) and the American Nurses Association (ANA) became increasingly concerned about the quality of delegation decisions. The NCSBN stated it believes that “state boards of nursing should regulate nursing assistive personnel” (NCSBN, 2005, p. 160). This means that it believes the current approach in many states of having certified nursing assistants regulated through the health or hospital division of the state no longer meets the needs of nursing. In addition, the NCSBN has added an expectation that basic training for nursing assistive personnel includes an emphasis on the concepts related to how to receive delegation. The ANA (2005) focused on the principles of delegation that an RN must use. Together they created a joint statement on delegation to guide nurses in their practice (Joint Statement, 2009). Basically, the statement acknowledges that the authority for delegation resides within the nursing practice act of each state, acknowledges the value of unlicensed personnel in meeting patient needs, and acknowledges that decisions should be made based on protection of the health, safety, and welfare of the public. In addition, the statement identifies that the decision to delegate tasks is based on a variety of complex factors such as the patient’s condition, the complexity of the task, and the predictability of outcomes. Although it is apparent that nursing’s need to delegate work will likely increase across the spectrum of care, content related to how to perform this task remains limited in schools of nursing, especially related to community settings. According to a report from the Nursing Executive Center of The Advisory Board Company (2008) of 36 competencies surveyed, nursing school leaders reported that they spent 1.8% of their instruction time teaching delegation. Of the six items with scores that tied this percentage or represented a lesser time, several related to delegation. For example, conflict resolution also represented 1.8% of the time, and conducting appropriate follow-up and ability to accept constructive criticism represented 1.7% and 1.6%, respectively. Although registered nurses do not supervise all unlicensed assistive personnel (e.g., physical therapy technicians), they often have exchanges with unlicensed nursing personnel and LPNs/LVNs. Further, only 10% of frontline leaders identified new graduates as proficient in delegation of tasks. Gaining experience and confidence in this important skill can enhance success early in the profession. Delegation can be further complicated by multiple cultural factors such as ethnicity, age, and gender. Although it might be possible to speak in generalities about each of those factors (e.g., saying men are better leaders than women), various studies have shown commonalities across these cultural differences. For example, Deal (2007) identified that there are differences among employees based on age. Younger generations, for instance, tend to morph rules to fit their logic, whereas the traditional generation follows the details of the rules. Although these generational differences exist, the differences tend to be in demonstrated behavior. The values tend to be comparable across generations. Delegate, or delegation, is defined in multiple ways. However, consistent elements can be found in each definition. Each definition calls for at least two people (a delegator and a delegatee), work, and some kind of transfer of authority and responsibility to perform the work. No definition suggests it is an abdication of accountability for the overall outcomes or performance or the abdication of the need to be involved. This is an important point because remaining in touch with others who are completing work on behalf of a delegator is sometimes difficult. Figure 26-1 shows that accountability remains fixed and that some portion of work is transferred along with the authority and responsibility for that delegated work. The importance of communication suggests that it must be constant to ensure basic, safe care. In fact, as tragic as Hurricane Katrina was when it struck in August 2005, critical healthcare lessons emerged. “Communication was the most critical factor in the determination to evacuate and the ease with which that process was completed” (McGlown, O’Connor, & Shewchuk, 2009, p. 277). Communication must be timely, often redundant, and reliable. A definition of delegation, therefore, might be as follows: achieving performance of care outcomes for which you are accountable and responsible by sharing activities with other individuals who have the appropriate authority to accomplish the work. Acceptance of the delegated work must occur, either passively (i.e., no protest occurs) or actively (i.e., communication indicates acceptance). Therefore delegation can occur only when two people are involved in a mutual work situation and one of the persons has accountability and the other has some authority for performing specific tasks. When two RNs work together sharing activities, delegation does not occur. However, if one RN has specific accountability for an outcome and that nurse asks another RN to perform a specific component of the overall function, that is delegation (see the “Assignment versus Delegation” section on p. 527 for further information). Delegation occurs when an RN assigns an LPN/LVN or UNP to perform a specific function or aspect of care. The term UNP incorporates a variety of workers, such as nursing assistants, orderlies, nurse associates, and patient care assistants. This role, as the word assistive conveys, provides help to the registered nurse who is accountable for care. Most UNPs today are prepared in some formal program, but that program may range from less than a week to several weeks. Consistency in preparation and job descriptions for UNPs is lacking! The NCSBN (www.ncsbn.org) has expressed concern about preparation inconsistency and suggests that programs and UNPs both need greater public accountability. Although the study is fairly old, Standing, Anthony, and Hertz (2001) found the two most common errors associated with poor patient outcomes related to (1) giving improper directions and (2) providing improper follow-through of agency protocol. These findings suggest that communication and agency protocols are crucial to achieving positive performance outcomes. Examples of improper directions could include not indicating when to report important findings or not alerting the delegatee to what the important findings might be. Examples of improper follow-through of agency protocol might be found when the delegator fails to validate findings that are not anticipated or when the delegator encourages the individual to perform functions beyond the stated position description for the delegatee. In addition, failure of the delegatee to report findings is an example of failure to follow through. Achieving performance outcomes is the driving force of all health care. If what someone does has little or no benefit in improving the delivery of care, it is, of course, ineffective. Therefore all care is based on attaining expected outcomes, whether that care is provided directly by an individual or group of professionals or whether that care was shared between professionals and assistants. Performance of care outcomes relates to the profession’s keeping its trust with the public, that is, to perform safely and competently. Standing et al. (2001) suggest that negative outcomes seem more related to delegation situations in which the nurse is less experienced in practice and the UNP is less experienced in a specific setting. In ever-changing healthcare settings, it is critical to know that you must delegate to achieve all that is expected of you. In essence, this means that if you cannot trust others or if you are frustrated because you cannot do it all yourself, you will be very frustrated with the way in which health care is delivered and your career opportunities will be fairly limited. Learning about another and developing trust are critical to success. Lencioni, in what is now an established, classic publication (2002), cites lack of trust as the number-one dysfunction of a team. Comfortable, confident delegation requires considerable trust to function as a smooth pairing. Hansten (2008) pointed out that few nurses planned specific times to check with assistive personnel and thus much time was spent looking for each other. She recommends a minimum number of checks being done before and after breaks and meals. The terms accountability and responsibility refer to the legal expectation the state has vested in persons with the designation of RN. Accountability means that someone must be able to explain actions and results. Legally, the RN is accountable for nursing care. Responsibility refers to reliability, dependability, and obligation to accomplish work. It also refers to each person’s obligation to perform at an acceptable level. Thus assistants, whether UNPs or LPNs/LVNs, are obligated to perform that which they can at acceptable quality levels. Those individuals are also responsible for informing the delegator what limitations, if any, would prevent the accomplishment of expected outcomes. The Code of Ethics for Nurses, Provision 4 (ANA, 2008), identifies the expectation of accountability and responsibility and makes specific reference to delegation. For example, even when some portion of care is delegated to someone else, each individual nurse is accountable and responsible for his or her practice, including the decision to delegate and the outcome of the delegated tasks.

Delegation

An Art of Professional Practice

Historical Perspective

Definition

Achieving Outcomes

Accountability and Responsibility

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access