Community Mental Health

Verna Benner Carson

Focus Questions

What is the philosophy of community mental health care?

Who are the severely mentally ill?

What are the needs of the severely mentally ill?

How are those needs met by community mental health?

What are the services available to meet the needs of the severely mentally ill?

Key Terms

Assertive community treatment (ACT)

Assisted outpatient treatment

Catchment area

Community mental health centers

Congregate or sheltered housing

Day treatment

Deinstitutionalization

Housing first

Individual placement and support method (IPS)

Institutionalization

Mental health parity

Mobile treatment units

Primary prevention

Revolving-door cycle

Secondary prevention

Severely mentally ill

Single-room occupancy

Tertiary prevention

In this chapter the concept, history, and significance of community mental health care are explored. Persons who receive community-based psychiatric services are identified, services are discussed, and the role of nursing in community mental health care is examined. The chapter provides an evaluation of community mental health care today and a discussion of its future directions.

Advent of community mental health care

Before 1963, community mental health care was nonexistent in the United States. Severely impaired individuals were admitted to psychiatric hospitals, where they frequently remained for the rest of their lives, forlorn, forgotten, and forsaken by family, professionals, and society. This all changed with the discovery of the phenothiazine drugs (e.g., chlorpromazine [Thorazine]). The effects of these drugs were nothing less than miraculous because they eliminated or reduced the most challenging of psychiatric symptoms. Suddenly, discharge became not only a possibility but also a reality for many individuals. Although patients were dramatically improved, they were not ready to reenter the community, nor was the community prepared to receive them. Many patients lacked family support, and some still exhibited behaviors that interfered with social interactions. Still other patients, accustomed to having needs met and decisions made by the institution, lacked the ability to function without institutional support. Therefore, these individuals were discharged from the state institution to a smaller institution, such as a nursing home or a group home. The condition of these individuals led to the recognition of the phenomenon of institutionalization; that is, long-term care in an institutional setting resulted in impaired social interaction, decision making, and independent living skills (Grob, 1994a; Stuart, 2009).

As more and more individuals became ready for discharge, the need for supportive services in the community became increasingly apparent. As awareness of this need grew among mental health professionals and the lay public, so also grew the awareness that the community was lacking these supportive services.

Legislative Changes in the 1960s

Concurrent with these changes, there were legislative mandates that focused psychiatry toward the community. In 1961, the Joint Commission on Mental Illness and Health published its report, which recommended that treatment of the mentally ill be moved from state hospitals to the community. The process of deinstitutionalization was underway with the goal of reducing the number of clients cared for in state hospitals by 50% over a two-decade period (Minkoff, 1978). In 1963, the U.S. government appropriated $150 million to fund community mental health centers through the Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Mental Health Centers Construction Act (Public Law 88–164, frequently referred to as the Community Mental Health Act). This money was to be matched by state funds over a 3-year period and used for the construction of comprehensive community mental health centers. For states to qualify for federal funding, they were required to provide five essential services: inpatient care, outpatient care, partial hospitalization, emergency care, and consultation and education. The expectation was that after 8 years, financial support of the centers would come from state and local funds and fees generated from services offered.

Before the system had a chance to get firmly established, while the available community resources were in the infancy stage of development, hospitals began to discharge large numbers of clients. Communities were unprepared to receive these clients. The system was fragile and incomplete. Financial support was lacking, housing and treatment facilities were scarce, and community attitudes were inhospitable to the individuals who were discharged. Psychiatric clients were feared, mocked, generally misunderstood, and stigmatized for conditions over which they had little or no control. Proposals for housing facilities in residential neighborhoods met with cries of indignation, alarm, and fear from residents. Communities felt that they had become “dumping grounds” for the large psychiatric hospitals. Former hospital residents, who were largely unwelcome and rebuffed, found that life outside the hospital was frightening and unappealing. They found themselves caught up in a revolving-door cycle of short inpatient stay, rapid discharge, and eventual repeat admissions.

Moving Forward in the 1970s

By the beginning of the 1970s, it was clear that there were real problems in the community mental health care movement. Among these problems was the fact that many state and local governments were not able to match federal funds. Some community mental health centers located in rural or poverty-stricken areas were unable to generate the necessary fees to be self-sufficient. Important services that generated little or no income, such as public education and consultation, began to suffer.

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter mandated a major reassessment of mental health needs. He established a 20-member President’s Commission on Mental Health that included a nurse, Martha Mitchell, who was the Chairperson of the American Nurses Association Division on Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing Practice. In 1978, the Report to the President of the President’s Commission on Mental Health was published and focused on strengthening the community mental health care system as the foundation for the mental health system. This would involve improving community support systems, continuing the phase-out of large public hospitals, establishing a center with a focus on primary prevention within the National Institute of Mental Health, and improving the delivery of services to underserved and high-risk populations. The report also advocated other major changes in the delivery of mental health care. These suggestions included the following:

• Establishing national health insurance that includes coverage for mental health.

• Developing advocacy programs for the chronically mentally ill.

• Protecting the rights of all persons in need of mental health services.

• Increasing support for research related to mental health and illness.

• Centralizing the evaluation efforts of governmental agencies.

This commission’s report was the first official high-level document to recognize the professional contributions of nurses to mental health care.

Losing Ground in the 1980s

In 1980, the Community Mental Health Systems Act was passed. It was designed to implement the recommendations of the president’s commission and to coordinate the two-tiered mental health system that had evolved since the original 1963 legislation that mandated the establishment of community mental health centers. Those with severe mental disability still resided within state institutions, and those who were less disabled used the services of the community mental health centers.

The programs authorized by this legislation were to be implemented in 1982, but before this could occur, there was a significant retrenchment by the federal government in terms of its responsibilities in the area of mental health. The Ninety-seventh Congress essentially repealed the 1980 Community Mental Health Systems Act with the passage of the Reagan administration’s Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (Public Law 97-35). This bill moved the authority for and administration of mental health programs from the National Institute of Mental Health to the individual states. Each state received a block grant to cover alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health services. As of 1984, federal funding for community mental health care and other mental health care delivery programs was terminated. The continued existence of community mental health centers was dependent on state support, private funding, and the center’s ability to earn revenue.

Doing More with Less in the 1990s

As the 1990s unfolded it became clear that reliance on federal funding was inadequate. The political climate favored the support of “smaller” rather than “bigger” programs directed to meeting human needs. With so many programs competing for limited funds, community mental health care was challenged to do more with less. The trend moved increasingly toward managed care (Grob, 1994b), which ultimately meant less care for those with severe mental disabilities.

Another major innovation of the 1990s was the involvement of recipients of services in the planning efforts (Chamberlin & Rogers, 1990). The prime motivation for this change came from organizations of former hospital residents, which began in the early 1970s. Members have traditionally joined these groups as a way of reclaiming their voice and being heard by a system that has considered them incapable of defining their own needs. A primary goal of these groups is influencing public policy related to implementation of mental health programs. These groups influenced the passage of legislation such as Public Law 99-660. This law requires the participation of various constituencies, including families, individuals with mental disorders, and professionals, in the planning of a community-based system of mental health care. It also provides a way for former residents of mental hospitals and their families to promote their vision regarding how care should and should not be given to people who suffer with mental disorders.

It became fashionable during the 1990s to refer to patients as consumers, a term that many formerly hospitalized patients find objectionable. The term consumer implies choice and power, a misnomer considering that clients in the mental health system are captive populations who have little choice regarding the services or the providers selected.

Additional changes in the 1990s included the closure of entire state psychiatric hospital systems with the wholesale transfer of large numbers of institutionalized severely mentally ill individuals into unprepared communities. At the same time, there was an increase in self-help programs, which are user-run programs that serve as drop-in centers and offer peer case management. Such services provide former patients with a feeling that they can make a difference to someone else, that they can give as well as receive, and that their lives have meaning.

Surviving in the New Millennium

Funding continues to be a major challenge to all community-based providers and has led to the mass closing of psychiatric hospitals across the United States. In a document titled More Mentally Ill Persons Are in Jails and Prisons than Hospitals: A Survey of the States (Torrey et al., 2010), Dr. E. Fuller Torrey, a long-time advocate for appropriate treatment for the seriously mentally ill, asserts the following:

Dr. Torrey and his fellow researchers concluded that the United States has returned to the conditions of the 1840s, when mentally ill persons filled America’s jails and prisons. This situation only improved as a result of a reform movement, sparked by a nurse named Dorothea Dix, who advocated for more humane treatment of the mentally ill (Torrey et al., 2010).

Instead of receiving treatment, many live on the streets, where they comprise about one-third of all the homeless—between 150,000 and 200,000 people—of the estimated 744,000 homeless population. The quality of life for these individuals is abysmal (Treatment Advocacy Center, 2011). Refer to Chapter 21 for additional information about homelessness, poverty, and the mentally ill. Dr. Fuller Torrey, president of the Treatment Advocacy Center, states, “The Los Angeles County jail with 3400 mentally ill prisoners is de facto the largest psychiatric inpatient facility in the United States. New York’s Rikers Island jail, with 2800 mentally ill prisoners, is the second largest” (Lowry, 2003). The mental health objectives in Healthy People 2020 are especially relevant to this large group of severely mentally ill individuals, who receive little to no treatment (see the Healthy People 2020 box).

In 2002, the New Freedom Commission on Mental Health was created by President George W. Bush. The commission released its report to the president in July 2003. The report was titled Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health in America. Commissioners concluded that services for the mentally ill were fragmented and inefficient, particularly for the severely mentally ill. For example, services varied from state to state, with blurring of responsibility among agencies, programs, and levels of government. Many clients were noted to “fall through the cracks.” Even those who received treatment had difficulty achieving financial independence because of limited job opportunities and the fear of losing health insurance in the workplace (President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003). Despite the conclusions of this commission and its recommendations for change in the mental health system, the delivery of mental health services is largely under the domain of individual states without an overriding federal mandate for change (New Freedom Commission on Mental Health State Implementation Activities, 2004).

In 2007 and 2008, there was a push in the U.S. Congress for expansion of the mental health parity law passed in 1996 (Pear, 2007; U.S. Department of Labor, 2007). Health insurance traditionally provides less coverage and more restrictions for mental health care than for physical health care. Mental health parity means that insurance coverage for treatment of mental illness would be the same as for medical and surgical treatment (Krauss & O’Sullivan, 2007). Congress passed the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008, a comprehensive mental health and addiction parity legislation in honor of the late Senator Paul Wellstone. This bill went into effect January 1, 2010 and provides the following:

• Encourage preventive mental health care and early intervention. Remove stigma and encourage plan members to seek mental health support for high stress and depression. Prevention and early intervention can help avoid more costly services that result from untreated conditions (American Psychological Association Practice Organization, 2011).

Local communities faced with managing the needs of the severely mentally ill have taken matters into their own hands by passing state legislation. Unique partnerships among law enforcement agencies, providers of drug and alcohol services, mental health and retardation service providers, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), consumer advocacy groups, and housing authorities have been formed to address the shortcomings of the community mental health system (Royer, 2003; Stratton, 2002). An example of a local community’s taking action occurred in New York with the passage of Timothy’s Law, signed by Governor George Pataki in December 2006. This state law went into effect in January 2007 as a result of local community efforts to address the inequities in mental health coverage.

The lightning rod for this community effort was the suicide in 2001 of a 12-year-old boy, Timothy O’Clair, who hanged himself in his bedroom closet. Timothy and his family had sought mental health care for almost 5 years. Because of the inequality between health care coverage for medical and mental health problems, Timothy’s care was sporadic, expensive, and never adequate to help him achieve remission. To obtain better care for Timothy, Mr. and Mrs. O’Clair were forced to relinquish custody of the boy and place him in the foster care system so that Timothy would be eligible for Medicaid coverage and unrestricted access to mental health services. Once in the foster care system Timothy bounced around several placements and finally ended up in Northeast Parent Child Society, where he seemed to improve. He came home to celebrate his mother’s birthday, and for 3 weeks he did well. Although the family continued to participate in therapy, Timothy became violent and threatened to kill himself—a threat he had made many times over the years. This last time he was serious, and while his dad was working and his mother was out with his brother, Timothy hanged himself (TimothysLaw.org, 2006).

Timothy’s Law requires that all group health insurance and health maintenance organization–type plans provide at least 30 inpatient days and 20 outpatient visits per year for mental health treatment. The cost of this benefit to small businesses with 50 or fewer employees is subsidized by New York State’s general fund. The law also requires large employers to provide unlimited treatment for adults and children who have biologically based mental disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar and delusional disorders, major depression, panic disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorders, bulimia and anorexia, and psychotic disorders (New York State United Teachers, 2006).

Another community mental health issue facing the country in the new millennium is the mental health needs of veterans returning from the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts who suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In 2008, the RAND Corporation, Center for Military Health Policy Research, published a population-based study that examined the prevalence of PTSD among previously deployed Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom (Afghanistan and Iraq) service members. Among the 1938 participants, the prevalence of current PTSD was 13.8% (Tanielian & Jaycox, 2008). Although many will be treated through the Veterans Administration system, problems related to the sequelae to PTSD will ripple throughout the community with an increase in divorce, joblessness, and homelessness (Vedantam, 2006).

Still another issue facing the United States is the exploding numbers of those with Alzheimer disease. Today one in eight people 65 years of age and older—5.2 million Americans—has Alzheimer disease. However, in 2011 baby boomers began turning 65 at a rate of about 7000 per day. The sheer number of baby boomers promises to dramatically increase the numbers of those with Alzheimer disease. About 13% of the population today is 65 years or older; by 2030, when the last of the baby boomers are 65, that rate will have grown to 18%. In addition to testing the sustainability of entitlement programs like Social Security, these numbers raise serious questions regarding who will be the caregivers to these older adults with Alzheimer disease or another dementia. Today 70% of those with this disease are cared for at home by a combination of family and paid caregivers. How will the nation manage the magnitude of these future care needs? (Carson, 2011; Carson & Smarr, 2006).

Philosophy of community mental health care

The philosophy of community mental health care has a two-pronged focus. The first is to consider the community as client and attempt to improve situations in the community that detract from optimal mental health and could conceivably lead to mental illness. This focus is embodied in educational and consultation programs.

The second focus is to consider the individual within the community as client. To serve the individual, a full range of comprehensive services is provided. These include the following:

Other services may also be available, including those designed to meet the needs of children, adolescents, and older adults; alcohol and drug abuse services; and transitional services.

The community is defined in terms of a catchment area, which is a city or several rural communities whose total population ranges from 75,000 to 200,000 residents. The intent of this approach is to divide the larger population into manageable segments for the delivery of mental health services. Ideally, the system is small enough to allow collaboration among the components of the system.

Care That is Continuous and Comprehensive

The stated goals of community mental health care are to provide care that is continuous and comprehensive. The goal of providing continuous care means ensuring that if individual clients are receiving care from different parts of the health care system, the providers are assuming responsibility for monitoring that care and assisting the clients in moving through the system. Ideally, there is a communication interface between programs so that individual clients do not feel that they are left to fend for themselves but rather that the road has been paved for them as they obtain a variety of needed services. Moving through the system should be smooth and appear seamless. Unfortunately, community mental health care has a long way to go before realizing the goal of providing continuity of care.

The goal of providing comprehensive care recognizes that people with severe mental illnesses have complex and multifaceted medical, nursing, and social needs, and each of these needs must be met using an integrated approach that is continually mindful of the holistic nature of the individual client.

Population served by community mental health care

Primarily, community mental health care serves the needs of those with severe mental illnesses. These illnesses are chronic with exacerbations and remissions as part of their course. Had it not been for the community mental health movement, many of those with severe mental illnesses might have been in mental institutions providing long-term care, especially state psychiatric hospitals.

Prevalence of Mental Disorders

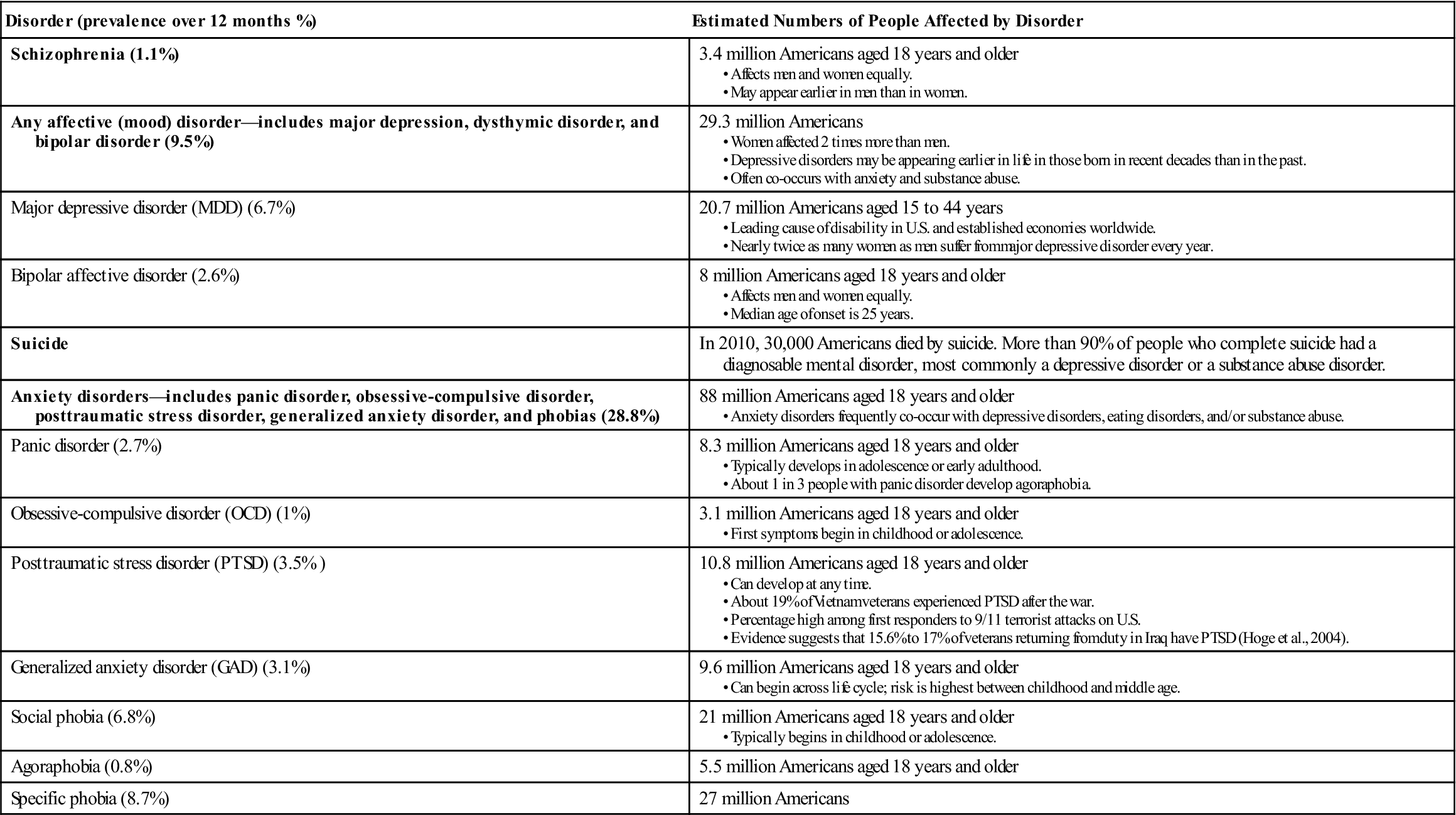

The National Institute of Mental Health (2008) provides a summary of statistics describing the prevalence of mental disorders in the United States. According to this summary, an estimated 26.2% of Americans aged 18 years and older—about one in four adults—suffers from a diagnosable mental disorder annually. When this percentage is applied to the 2010 U.S. Census residential population estimate for those aged 18 years and older, this figure translates to 80.9 million people with mental disorders. Mental disorders are the leading cause of disability in the United States and Canada for individuals aged 15 to 44 years. Many individuals have more than one mental disorder at the same time. Table 33-1 shows the prevalence of selected psychiatric disorders in the United States. All prevalences are higher than in 2006.

Table 33-1

Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders in the United States

Data from National Institute of Mental Health. (2011, September 18). http://www.nimh.nih.gov/statistics/index.shtml.; Hoge, C., Castro, C., Messer, S., et al. (2004). Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine, 351(1), 13-22; and Tanielian, T., & Jaycox, L. (Eds.), (2008). Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Who Are the Severely Mentally Ill?

The severely mentally ill are a diverse group with a variety of diagnoses, including schizophrenia, major affective disorders, and organic disorders secondary to trauma, disease, or substance abuse. They include older adults with chronic and severe mental illnesses, who may reside independently with supportive family nearby or with a supportive network of caring people. This supportive network might include the landlord, the mail carrier, the local grocer, and others who look out for the welfare of the individual. Some of these older adults with severe mental illnesses live with family and friends; some live in supervised housing, such as foster care or nursing homes. Robert Bernstein, executive director of the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, believes that “many older people with mental illnesses or dementia are still isolated in nursing homes and other institutions, where they receive no more than custodial care” (Bernstein, 2003, p. 10).

Individuals with schizophrenia may hold jobs in the community during periods when symptoms are in remission; those with residual symptoms that interfere with their functional capacity rely on disability checks and sporadic employment. They also may reside in foster or group homes. Some seek shelter in decrepit urban hotels, whereas others take to the street and end up in shelters for the homeless. In rural areas, the chronically mentally ill may live in the woods, in abandoned buildings, or under bridges. Some of those with severe mental illnesses reside inappropriately in prisons.

Many are living with serious medical conditions, such as extreme obesity, diabetes, and cardiac and respiratory problems as well as hepatitis C, which occurs among those with severe mental illness at a rate of 10 times the national average (Goldbaum, 2003). Estimates are that 1.8% of Americans are infected with hepatitis C, and approximately 20% of those have severe mental illness (Patterson, 2003). The incidence of hepatitis C corresponds with the fact that many have complicating patterns of substance abuse—both issues are tied to the same risky behaviors that increase the likelihood of acquiring the bloodborne virus (see Chapters 8 and 25). For many of the severely mentally ill, substance abuse is a primary problem. For others, substance abuse may be an attempt to self-medicate to ease the pain of a difficult life (Bostelman et al., 1994; Conway et al., 1994; Drake & Mueser, 2000).

The population of severely mentally ill includes a range of ages, from the very young who have never experienced long-term institutionalization to the very old who suffer from deinstitutionalization. All experience problems of being emotionally and mentally disabled and must live with the stigma of mental illness. Sheets and colleagues (1982) identified three subgroups among the young chronically mentally ill, those from 18 to 30 years of age. There is a high-functioning group, a passively accepting (low-energy, low-demand) group, and a group who actively deny that they have mental illness (high-energy, high-demand subgroup). Those who aggressively deny the reality of their illness have the most difficulty accepting any help, including supervised housing. They prefer the independence of hotels and the streets. Those who choose to live with limited interpersonal contact may withdraw, may neglect themselves, may stop taking their medications, and are especially vulnerable to exploitation by others. There are successes in working with these clients; some are persuaded to accept help within the community mental health care system, even to accept residential living arrangements (Wierdsma et al., 2007). The following example illustrates the characteristics of a young adult who is severely mentally ill.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree