Community Diagnosis, Planning, and Intervention

Frances A. Maurer and Claudia M. Smith

Focus Questions

What is the history of contemporary health planning in the United States?

How do models of community organization relate to health planning?

What principles and steps can assist the nurse and community in developing an effective plan?

What are examples of community diagnoses?

How are priorities determined in health planning with communities?

What are common types of interventions typically planned by community/public health nurses?

Key Terms

Community empowerment

Community organization models

Data gap

Gantt Chart

Management objectives

North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA) classification system

Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC)

Omaha System

Outcome objectives

Planned Approach to Community Health (PATCH)

Planning, Programming, and Budgeting System (PPBS)

Population-focused health planning

Process objectives

Program Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT)

Social action

Social planning

Target population

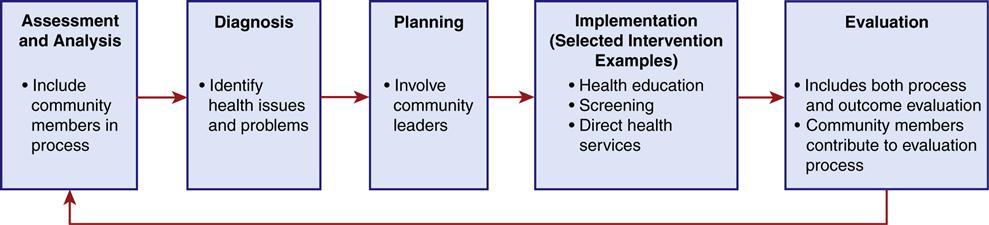

Chapter 15 provides community/public health nurses with the basics of community assessment, the first step in the nursing process. The chapter illustrates the use of a systems-based community assessment tool to assist nurses in gathering information about a community. This chapter continues the nursing process with communities (Figure 16-1), introducing the process of planning and implementing population-focused health care in communities. The components of and steps used in program planning, the types of interventions appropriate for the community level, and the responsibilities of the community/public nurse in planning and implementing care with populations are described. The nursing process is dynamic, not static, as the arrows in the figure illustrate. Health intervention plans may be modified as new information becomes available. It is important to include community members in as many steps in the process as possible. Input from the population(s) should be elicited regarding analyzing the assessment data to determine population diagnoses and priorities, identifying desired outcomes, planning, and evaluation (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2007).

Population-focused health planning

Health planning is a continuous social process by which data about clients are collected and analyzed for the purpose of developing a plan to generate new ideas, meet identified client needs, solve health problems, and guide changes in health care delivery. To date, you have been responsible primarily for developing a plan of care for the individual client. How do you go about developing a plan of action to meet the health needs of a community? How is the plan different from that for the health of an individual or a family? What types of nursing actions and interventions are appropriate for the community?

Population Targets and Intervention Levels

Population-focused health planning is the application of a problem-solving process to a particular population. In population-focused health planning, communities are assessed, needs and problems are prioritized, desired outcomes are determined, and strategies to achieve the outcomes are delineated.

Persons for whom you desire change to occur are referred to as the target population. Planning care for groups or populations results in programs, and hence the term program planning is often used when planning care at the community level.

Programs may be aimed at the primary, secondary, or tertiary level of prevention. For example, a health education program about safer sex is aimed at preventing sexually transmitted diseases through health-promotion measures (primary prevention); a program to screen preadolescent girls for scoliosis is geared toward early detection and treatment (secondary prevention); and an exercise program for stroke victims to limit or minimize their disability is an example of a tertiary level of prevention.

Population-focused health planning can range from planning health care for a small group of people to planning care for a large aggregate or an entire city, state, or nation. The planning process described in this chapter is applicable to all types of communities (phenomenological and geopolitical) and to all levels of planning (local, state, national, and international). Health planning can be proactive or reactive. The goal is to use a more proactive approach and for nurses to be an integral part of the planning process.

History of U.S. Health Planning

The history of health planning in the United States has alternated between the federal and state governments. Before the 1960s, health planning occurred primarily at the state level. In the 1960s, health planning became a federal effort. In 1966, the Comprehensive Health Planning and Public Health Service Amendment was passed to enable states and local communities to plan for better health resources. Inadequate funding allocation led to the National Health Planning and Resources Development Act of 1974. This legislation created a national network of health system agencies and statewide coordinating councils responsible for health planning. The intent was to improve health status and care, while reducing cost. These goals were to be achieved by preventing unneeded or duplicate services, decreasing fragmentation of services, and coordinating resources. New services were encouraged based on regional needs assessments.

In the 1980s, President Reagan aimed to reduce both the size of the federal government and the influence the federal government had on states. His administration eliminated the federal budget and planning requirements while encouraging states to make their own planning decisions. The federal health objectives for the years 2000, 2010, and 2020 suggest targets for local communities and states to consider (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010a).

Increasing costs have placed heavy demands on the health care system (see Chapters 3 and 4). As a result health planning has essentially become economically focused. The federal government has attempted to control its share of health care costs by changing reimbursement methods, and shifting some of the budget responsibilities to the states. Because the federal government mandates health care services in those specific programs, states are left with limited autonomy to plan and deliver health care services.

In 1980, the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act encouraged the use of noninstitutional services, such as home health care, to fight escalating costs. In 1983 the Prospective Payment System drastically changed hospital reimbursement, resulted in shorter hospital stays for patients, shifted care into the community, and placed greater responsibilities for care of relatives on family members (see Chapters 3 4 and 28).

The Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Budget and Deficit Control Act of 1985 added additional budget controls and cutbacks to health care. Taken together, these and subsequent federal efforts have presented a challenge to all health care professionals to plan and implement cost-effective health care programs that meet the needs of the people they serve. It is imperative that nurses become more cognizant of the health care planning process and their role within it.

The 1990s and early 2000s offered new opportunities for nurses to be involved in efforts to reform the nation’s health care system (ANA, 1991). Debate continues about the degree to which government should be involved in health planning and whether federal or state planning is preferred (see Chapter 3). The federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Affordable Care Act) of 2010 requires access to health care for most Americans. Some states have already passed their own health care legislation, ensuring access to health care, identifying standard health benefit packages, and budgeting or requiring finance mechanisms. A greater interest has developed in ensuring that planning efforts also address the quality of health care. Furthermore, Healthy People 2020 includes a goal that federal, state, and local public health infrastructures should have the capacity to provide essential public health services (USDHHS, 2010a).

Health care planning for specific geopolitical communities continues at the state and local levels. Community/public health nurses are involved with specific communities to assess community needs. Nurses explore how the Healthy People 2020 objectives apply to these geopolitical or phenomenological communities. Based on the assessments, community/public health nurses participate with others to develop plans to meet the health care needs of the people.

There are federal requirements for hospitals to report in detail their community benefits activities (uncompensated care and other services) to the Secretary of the Treasury (Internal Revenue Service, 2011). In addition the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act requires tax-exempt hospitals to do a community-needs assessment every three years. That assessment is intended to assist in planning how to best use hospital resources to the community’s benefit (Public Law 148, 2010).

Rationale for Nursing Involvement in the Health Planning Process

Florence Nightingale and Lillian Wald pioneered health planning based on an assessment of the health needs of the communities they served (see Chapter 2). Additionally, nurses have long been involved in implementing programs planned by other disciplines. Both the American Nurses Association (ANA) (2007) and the American Public Health Association (APHA) (1996) state that the primary responsibility of community/public health nurses is to the community or population as a whole and that nurses must acknowledge the need for comprehensive health planning to implement this responsibility. Both professional organizations identify program planning as a primary function of the community/public health nurse.

In addition to mandates from professional organizations, nurses should be involved in program planning for several reasons. Nurses make up more than one-third of all health care workers in the United States and implement the majority of health care programs. Our involvement in numerous and diverse health programs has given us experience in seeing what works and what does not. This experience helps identify difficulties that can be avoided in the future.

Nurses spend a greater amount of time in direct contact with their clients than do any other health care professionals. We are with the clients in the community, gaining first-hand information about their health, their lifestyles, their needs, and what it is like to be a member of that community. This exposure to the community places us in the unique position of possessing valuable information that is useful to the planning and implementation of successful health programs.

Not only do nurses make up a large portion of health care providers, they also make up a large portion of health care consumers in the United States. With the emphasis on consumer participation in health planning, nurses are in a unique position to make an impact in the planning of population-focused health programs.

Nursing Role in Program Planning

Planning for change at the community level is more complex than at the individual level. Components to the client system have been increased, and more people and more complex organizations are involved. Baccalaureate-prepared community/public nurses are expected to apply the nursing process with subpopulations or aggregates with limited supervision (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 1986; ANA, 2007). If nurses practice in agencies with a broad public health mandate, they will find that the scope of their focus shifts to larger populations (APHA, 1996). Community/public health nurses prepared at the baccalaureate level are expected to collaborate with others to assess the entire population and multiple aggregates in a geopolitical community (ANA, 2007). Therefore community health planning often takes a multidisciplinary approach, which requires excellent teamwork and thorough communication. The roles of collaborator, coordinator, and facilitator are important when working with the community as client.

A necessary task is to collaborate with people from the community to validate nursing diagnoses made from the assessment; to plan with, not for, the community; and to enlist community members’ support and assistance in implementing change. If the community is not involved from the beginning, the program may not be effective. Just as you will have better adherence and outcome from planning care with an individual client, so, too, you will have a more successful program if you involve the community in the assessment and planning phases.

The coordinator role emerges when working with a variety of community members and organizations within and outside of the community. The nurse is in a key position to coordinate the activities and facilitate the community’s ability to achieve a higher level of health. However, to effect change at the community level, community organization must be understood.

Planning for community change

To plan and implement programs at a community level effectively, the community/public health nurse must understand how the community works, how it is organized, who its key leaders are, how the community has approached similar problems, and how other programs have been introduced in the past. The health care professional who is facilitating the community organization process with regard to a specific health need or problem must work with the community members. To be an effective change agent in applying the nursing process, the nurse must be aware not only of the community and how it works, but also of methods of community organization that facilitate change.

Community Organization Models

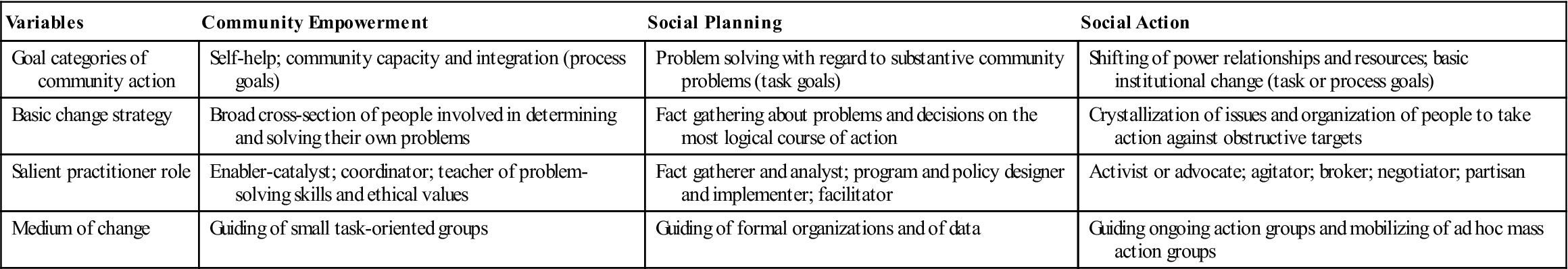

Rothman (1978, 2008) identifies three community organization models designed to facilitate change in a community: community development (now called empowerment), social planning, and social action. The three models can be used separately or in combination. Although the models are presented here in pure form, in reality, they are generally combined. Social planning was the model most used by community health nurses and other public health care practitioners between the 1970s and the early 1990s. However, community organization approaches used by Lillian Wald and others during the nineteenth century, as well as during the 1960s, are reemerging as models for community empowerment.

Each model contains four components: goals, strategy, practitioner role, and medium of change. Table 16-1 summarizes the salient points from each of the three models. A thorough understanding of the components is necessary in planning for change in a community. Each model involves community change.

Table 16-1

Three Models of Community Organization Practice According to Selected Practice Variables

| Variables | Community Empowerment | Social Planning | Social Action |

| Goal categories of community action | Self-help; community capacity and integration (process goals) | Problem solving with regard to substantive community problems (task goals) | Shifting of power relationships and resources; basic institutional change (task or process goals) |

| Basic change strategy | Broad cross-section of people involved in determining and solving their own problems | Fact gathering about problems and decisions on the most logical course of action | Crystallization of issues and organization of people to take action against obstructive targets |

| Salient practitioner role | Enabler-catalyst; coordinator; teacher of problem-solving skills and ethical values | Fact gatherer and analyst; program and policy designer and implementer; facilitator | Activist or advocate; agitator; broker; negotiator; partisan |

| Medium of change | Guiding of small task-oriented groups | Guiding of formal organizations and of data | Guiding ongoing action groups and mobilizing of ad hoc mass action groups |

Adapted from Rothman, J. (1978). Three models of community organization practice. In F. Cox, J. Erlich, J. Rothman, et al. (Eds.), Strategies of community organization: A book of readings (pp. 25-45). Itasca, IL: Peacock Publications; and Rothman, J. (2008). Approaches to community intervention. In J. Rothman, J. Erlich, & J. Tropman (Eds.), Strategies of community intervention (7th ed., p. 163). Peosta, IA: Eddie Bowers Publishing Company.

Community Empowerment Models

The community empowerment model is an approach designed to create conditions of economic and social progress for the whole community and involves the community in active participation. The community empowerment approach is also referred to as the locality development approach because of its work within the community. The community-locality development model is a grassroots approach that uses a democratic decision-making process, encourages self-help, seeks voluntary cooperation from the members, and develops leadership within the group (Milio, 1971). In this approach, community members believe they have some control over their destiny and therefore become actively involved. The change strategy is characterized by, “We know we have a problem, let’s get together and discuss it.” The theory underlying this model is that if people are involved in determining their own needs and desires, they will become more active in solving their problems than if someone else comes in and solves the problems for them. If they are more active in working out solutions to their own problems, they will be more satisfied with the solutions and will continue to expend energy to make them work. That is, if they are vested in the solutions, they will have more of a commitment to them. The solutions will be more sustainable (Bent, 2003). This model seeks to build on community assets and strengthen community competence.

The community empowerment model is especially important for communities with vulnerable and underserved populations. This model is being used successfully in both urban and rural communities.

This approach, then, has the potential of having the longest lasting effect of the three models to be discussed. However, the task is also the most time-consuming to initiate because time is required to discuss the problems, to make decisions democratically, and to develop leadership within the group that will be able to sustain the program. Therefore even though the community-locality development approach to community organization is successful, it may not always be used in pure form because of the amount of time required to accomplish the action.

Social Planning Model

The social planning approach emphasizes a process of rational, deliberate problem solving to bring about controlled change for social problems. This method is an expert approach in which knowledgeable people (experts) take responsibility for solving problems. The degree of community involvement may be very small or very great. (The greater the involvement is, the more successful the outcome will be.) The social planning approach is characterized by, “Let’s get the facts and proceed logically in a systematic manner to solve the problem.” Pertinent data are considered before decisions are made about a feasible course of action to meet the need.

Agencies and organizations frequently use this approach as they attempt to effect desired change. The legislative and regulatory process is one example of a social planning approach. Problems are identified, data are collected, and bills are introduced into local, state, or national legislative bodies to effect change. A social planning approach is also used when a local health department institutes a program of directly observed therapy for treating tuberculosis. Public health nurses use facts gathered about the prevalence of tuberculosis in the community, as well as public health and nursing literature about effective treatment programs, to plan a program to directly observe persons with active tuberculosis take their antituberculosis medications.

The social planning approach can be effective, but it has one major pitfall: the potential for lack of community involvement. Much money has been spent and many health programs have failed because experts have planned programs for the community instead of with the community. The health planners, the nurse experts, must develop a partnership with the community for effective health care planning (ANA, 2007).

Social Action Model

The social action approach is a process in which a direct, often confrontational, action mode seeks redistribution of power, resources, or decision making in the community or a change in the basic policies of formal organizations, or both. In this approach, one group of people or segment of an organization or community is feeling oppressed, and the organization or community is viewed as needing basic changes in its institutions or practices. Nonviolent civil disobedience or aggressive actions may be taken to facilitate these changes. This approach, which is direct and often confrontational and radical, may be characterized as follows: “Let’s organize to rectify an imbalance of power.” In the 1960s the social action approach was used a great deal. The civil rights movements and protests against the Vietnam War are examples of the social action approach. Current examples include welfare rights organizations and advocacy groups for the environment or for the homeless, as well as some antiabortion groups.

Change Theory

Each of the community organization models involves change. Change can be threatening and stressful or it can be exciting and rewarding. Understanding some theory about planned change will provide a guide to use in the planning process. Lewin (cited in Dever, 1991) describes change as being a three-stage process: unfreezing, moving, and refreezing. In the first stage, unfreezing, a need for change is identified. The stimulus for the perceived need may be within the client or come from an outside force. Disequilibrium exists or is created, making a disruption in the status quo (unfreezing), and change is initiated. Moving, the second stage of the change process, occurs when the proposed change is tried out by the people involved, old actions are questioned, and attitude changes occur, creating movement toward acceptance of the proposed change. This phase is a vulnerable time for the people involved, because change is threatening and anxiety producing. Individuals will need help and support while trying out the proposed change. Refreezing, the third stage of the change process, occurs when the change is established and accepted as a permanent part of the system. Stabilization of the situation occurs. Lewin also describes forces that facilitate (driving forces) or impede (restraining forces) change. Driving forces must exceed restraining forces for change to occur.

Structures for Health Planning

Several structures or schemes have been developed by national organizations to help communities plan for improving their health. These structures encourage collaborative partnerships and comprehensive assessments as building blocks for community health planning.

Planned Approach to Community Health (PATCH) is a program initiated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PATCH attempts to engage entire geopolitical communities in a comprehensive assessment of their health needs rather than focusing solely on high-risk groups or those served by a specific health institution. PATCH depends on the participation of citizens and the cooperation of several organizations within the community in partnership with local and state government resources.

The National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) developed a strategic planning tool, Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships (MAPP) (NACCHO, 2008). MAPP is intended for use by local health departments in planning with geopolitical communities to improve health status and public health system capacities (see Chapters 15 and 29). The tool emphasizes community ownership of the process. The action cycle of MAPP includes planning, implementation, and evaluation.

The World Health Organization adopted the Healthy Cities program in the 1980s to promote the health of urban communities (Kegler et al., 2009). Collaboration among multiple community sectors and community participation are hallmarks of this model, which focuses on the role of local government in creating physical, social and economic environments that promote health (Rabinowitz, 2001). Over 3000 projects exist worldwide in both urban and rural areas.

The Healthy People 2020 objectives are introduced in Chapter 2 and used as examples throughout the text. Many state and local jurisdictions have developed health improvement plans that link the national perspective of Healthy People 2020 with local needs.

Steps of program planning

The planning process consists of a series of specific steps. Although each of these steps is necessary, the steps do not have to occur in the exact sequence given here. Occasionally, several steps may be undertaken simultaneously, or they may occur in a slightly different order. Identification of the planning group may occur much earlier in the sequence. The steps are as follows:

1. Assessment

2. Diagnosis

3. Validation

5. Identification of the target population

6. Identification of the planning group

7. Establishment of the program goal

8. Identification of possible solutions

9. Matching solutions with at-risk aggregates

10. Identification of resources

11. Selection of the best intervention strategy

12. Delineation of expected outcomes

13. Delineation of the intervention work plan

Some researchers call steps 8 through 14 operations planning (e.g., Hale et al., 1994).

Assessment

A thorough, accurate assessment of the community is the first essential step in program planning. Chapter 15 provides a framework for community assessment and assessments of a geopolitical and a phenomenological community.

Analysis of Data

A systematic analysis of the data collected is necessary to identify the problems, needs, strengths, and trends in the community. Categorizing the data first is always helpful to identify the inferences that are descriptive of actual or potential health problems. The community assessment described in Chapter 15 provides a framework in which to categorize the data about community functioning. Within each subsystem, nurses identify resources (assets, strengths) and demands (deficits, weaknesses), looking not only at whether something is present, but also to what extent, how it is working, and how it relates to the past and future to provide an idea of trends over time. Nurses also consider the health status of the population. Typically, the nurse identifies high-risk aggregates among the population as well.

In addition to illustrating the community’s strengths and weaknesses, an analysis will provide information about demographic and personal characteristics, which are important to consider when planning and implementing health programs. For example, if you are working with a group of senior citizens enrolled in a senior center and your assessment indicates a potential risk for injury by fire, what other factors should you consider in the assessment data before you plan a fire prevention program? One factor that comes to mind is the educational level of the senior citizens. Knowing the educational level provides information about the appropriate level at which to plan the teaching interventions. The level of disability and social functioning indicates the presence of visual or hearing impairments that might affect the type of teaching strategy you use. Additionally, if many seniors are in wheelchairs or need assistive devices, you would focus the program on fire safety involving limited mobility and would need to modify practice sessions to the participants’ level of ability. In other words, analysis of community data provides information not only about what is needed, but also about what will be appropriate in the intervention.

Data Gaps

Assessment sometimes reveals areas in which all the information is not available. This lack of information is called a data gap. The nurse must identify areas of insufficient information and devise a strategy to collect additional data if possible. Data gaps themselves may sometimes be informative. For example, if you cannot find out the date of a town council meeting, it might imply that the council is not open to citizen input.

Ways to Display Data for Analysis

As shown in Chapter 7, displaying data that aid in the analysis process can be done in a variety of ways. Graphs, charts, histograms, and mapping techniques are some of the most common visual displays. Computer-based geographical information systems (GIS) that map data spatially are becoming more widely used (see Chapter 15).

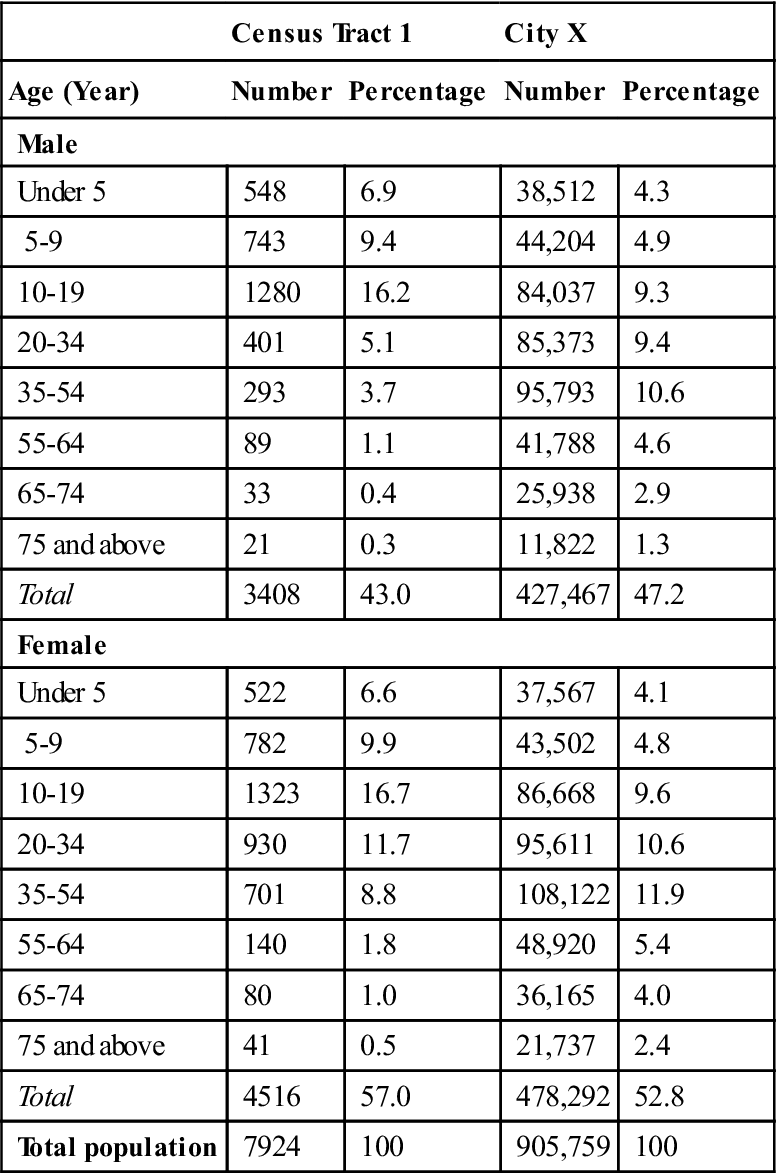

Obtaining as much data as possible that are specific to the target population is important. Table 16-2 includes the age and sex of people living in census tract 1 and city X. Census tract 1 data are included in city X totals, but, as can be seen, census tract 1 is quite different from city X. The population of the census tract is younger than the total city population, and data from the city cannot be used to describe the residents of the census tract. Looking at city X data only and thinking that the data would apply specifically to census tract 1 would not be accurate.

Table 16-2

Comparison of Age by Sex of Populations in Census Tract I and City X, 2000

| Census Tract 1 | City X | |||

| Age (Year) | Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage |

| Male | ||||

| Under 5 | 548 | 6.9 | 38,512 | 4.3 |

| 5-9 | 743 | 9.4 | 44,204 | 4.9 |

| 10-19 | 1280 | 16.2 | 84,037 | 9.3 |

| 20-34 | 401 | 5.1 | 85,373 | 9.4 |

| 35-54 | 293 | 3.7 | 95,793 | 10.6 |

| 55-64 | 89 | 1.1 | 41,788 | 4.6 |

| 65-74 | 33 | 0.4 | 25,938 | 2.9 |

| 75 and above | 21 | 0.3 | 11,822 | 1.3 |

| Total | 3408 | 43.0 | 427,467 | 47.2 |

| Female | ||||

| Under 5 | 522 | 6.6 | 37,567 | 4.1 |

| 5-9 | 782 | 9.9 | 43,502 | 4.8 |

| 10-19 | 1323 | 16.7 | 86,668 | 9.6 |

| 20-34 | 930 | 11.7 | 95,611 | 10.6 |

| 35-54 | 701 | 8.8 | 108,122 | 11.9 |

| 55-64 | 140 | 1.8 | 48,920 | 5.4 |

| 65-74 | 80 | 1.0 | 36,165 | 4.0 |

| 75 and above | 41 | 0.5 | 21,737 | 2.4 |

| Total | 4516 | 57.0 | 478,292 | 52.8 |

| Total population | 7924 | 100 | 905,759 | 100 |

Diagnosis

After analyzing the data, the next step is to make a definitive statement (diagnosis) identifying what the problem is or the needs are. Nursing diagnoses for communities may be formulated regarding the following issues:

• Inaccessible and unavailable services

• Mortality and morbidity rates

• Specific populations at risk for physical or emotional problems

• Health-promotion needs for specific populations

The format of the problem statement varies, depending on the philosophy of the agency conducting the assessment. For example, problems or needs may be stated simply in epidemiological terms, such as a high rate of adolescent pregnancies, whereas in other instances you may be asked to state the problem or need as a nursing diagnostic statement.

Nursing diagnosis has evolved since 1973 as a result of the efforts of the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA) (NANDA, 2009). The initial North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA) classification system of nursing diagnoses focused on the physical needs of individual clients but was not applicable to the family and community situations faced by community health nurses. Over the years, the NANDA classification system has expanded to include biological, psychological, and social needs of individuals and families. Because of ongoing refinement, the taxonomy of nursing diagnoses at present has 11 functional health patterns. Tools have been developed to assess the community using the functional health pattern typology (Gikow & Kucharski, 1987; Wright, 1985). Newer NANDA diagnoses may also apply to communities; examples include the diagnoses impaired home maintenance and impaired social interaction.

Other classification systems have been developed in an attempt to address the community. One example is the Omaha System, written by community/public health nurses for community/public health nursing practice (Martin, 2005). The system was designed by the Omaha Visiting Nurse Association and has been used in home care, public health, and school health practice settings, among others. Client problems/needs/concerns are organized into four domains: physiological, psychosocial, health-related behaviors, and environmental. Each domain may involve actual or potential problems or opportunities for health promotion. The system includes four categories of interventions: teaching, guidance, and counseling; treatments and procedures; case management; and surveillance. Although originally developed for application with individuals or families, users are now applying the problem domains and interventions with communities (Martin, 2005).The Omaha System includes more environmental and community factors than are considered in the NANDA system.

Because of the multiple nursing diagnostic and classification systems, the NNN Alliance has formed to develop a consistent classification system. The NNN Alliance is a collaboration of NANDA and the Center for Nursing Classification and Clinical Effectiveness (CNC). The taxonomy developed by the NNN Alliance has four domains (Dochterman & Jones, 2003). The one relevant to community health practice is the environmental domain, with three subsets: health care system, populations, and aggregates. All three subsets have diagnosis, outcome, and intervention arenas.

Because community/public health nursing is concerned with health promotion, other nurses have developed ways to add wellness diagnoses to the problem-focused diagnoses of NANDA. Neufield and Harrison (1990) recommend that wellness nursing diagnoses for populations and groups include three components: the name of the specific target population, the healthful response desired, and related host and environmental factors. For example, high school students with children (target population) have the potential for responsible parenting (desired response); this potential is related to a desire to learn about child development (host factor) and the presence of a family life education curriculum and an availability of teachers (environmental factor).

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, NANDA added several community-focused diagnoses: readiness for enhanced community coping, ineffective community coping (NANDA, 2002) and risk for contamination (NANDA, 2007). These diagnoses address a community’s ability to adapt and solve problems.

How does the nurse formulate a community-focused nursing diagnosis? A diagnosis is a statement that synthesizes assessment data; it is a label that describes a situation (state) and implies an etiological component (reason). A nursing diagnosis limits the diagnostic process to the diagnoses that represent human responses to actual or potential health problems that are within the legal scope of nursing practice.

A nursing diagnosis has three components: a descriptive statement of the problem, response, or state; identification of factors etiologically related to the problem; and signs and symptoms that are characteristic of the problem (Carpenito, 2000).

Using this information, let us take a moment to try to state nursing diagnoses for some problems on the community level.

Situation 1

Howard County is a suburban county with a rapidly increasing number of older adults. The assessment data indicate the presence of only one taxicab company serving that area. No public bus system is available.

Obviously, the problem is lack of transportation; but how might this be worded in nursing diagnosis format?

Suggestion:

Altered health-seeking behaviors related to inadequate transportation services for senior citizens

However, inadequate transportation probably also affects other areas of seniors’ lives, such as socialization and community participation. If this factor were validated through further assessment, an additional diagnosis might be as follows:

Impaired social interactions related to inadequate transportation for senior citizens

Situation 2

Students in Johnson High test very low on an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) awareness survey. Further investigation reveals that no information is provided to the students, and the parents do not want information taught in the school. Ninety-eight percent of the students stated that they do not believe they are in any danger of getting human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Suggestion:

Lack of knowledge about HIV/AIDS in high school students related to:

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree