Chapter 29 On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Identify communication strategies for interviewing parents. • Formulate guidelines for using an interpreter. • Identify communication strategies for communicating with children of different age-groups. • Describe four communication techniques that are useful with children. • State the components of a complete health history. • List three areas that are evaluated as part of nutritional assessment. • Prepare a child for a physical examination based on his or her developmental needs. • Perform a comprehensive physical examination in a sequence appropriate to the child’s age. • Recognize expected normal findings for children at various ages. • Record the physical examination according to the head-to-toe format. Introduce yourself, and ask the name of each family member who is present. Address parents or other adults by their appropriate titles, such as “Mr.” and “Mrs.,” unless they specify a preferred name. Record the preferred name on the medical record. Using formal address or their preferred names, rather than using first names or “mother” or “father,” conveys respect and regard for the parents or other caregivers (Seidel, Ball, Dains, et al., 2011). At the beginning of the visit, include children in the interaction by asking them their name, age, and other information. Nurses often direct all questions to adults, even when children are old enough to speak for themselves. This only terminates one extremely valuable source of information: the patient. When including the child, follow the general rules for communicating with children given in the Guidelines box on p. 775. The place where the nurse conducts the interview is almost as important as the interview itself. The physical environment should allow for as much privacy as possible, with distractions, such as interruptions, noise, or other visible activity, kept to a minimum. At times it is necessary to turn off a television, radio, or cellular telephone. The environment should also have some play provision for young children to keep them occupied during the parent-nurse interview (Fig. 29-1). Parents who are constantly interrupted by their children are unable to concentrate fully and tend to give brief answers to finish the interview as quickly as possible. Many institutions use computer and information applications in nursing (nursing informatics), such as electronic medical records, to record care and access information. Two important health care applications are (1) record transmission, including online access, fax, and e-mail; and (2) telemedicine. The telemedicine application is capable of two-way video conferencing, transmission of radiographs, and clinical consultation between remote sites and centralized resources.* Nurses are increasingly responsible for assessing children’s symptoms and applying clinical judgment for further medical care (triage) via telephone report. Most often, health problems are assessed and prioritized according to urgency and nurses provide treatment via telephone services. A well-designed telephone triage program is essential for safe, prompt, and consistent quality health care (Beaulieu and Humphreys, 2008; Marklund, Ström, Månsson, et al., 2007). Telephone triage is more than “just a phone call,” since a child’s life is a high price to pay for poorly managed or incompetent telephone assessment skills. Typically, guidelines for telephone triage include asking screening questions; determining when to immediately refer to emergency medical services (dial 911); and determining when to refer to same-day appointments, appointments in 24 to 72 hours, appointments in 4 days or more, or home care (Box 29-1). Successful outcomes are based on the consistency and accuracy of the information provided. Telephone triage care management has increased access to high-quality health care services and empowered parents to participate in their child’s medical care. Consequently, patient satisfaction has significantly improved. Unnecessary emergency department and clinic visits have decreased, saving medical costs and time (with less absence from work) for families in need of health care. Although it is necessary to make some preliminary judgments, listen with as much objectivity as possible by clarifying meanings and attempting to see the situation from the parent’s point of view. Effective interviewers consciously control their reactions, responses, and the techniques they use (see Cultural Competence box). Silence as a response is often one of the most difficult interviewing techniques to learn. The interviewer requires a sense of confidence and comfort to allow the interviewee space in which to think without interruptions. Silence permits the interviewee to sort out thoughts and feelings and search for responses to questions. Silence can also be a cue for the interviewer to go more slowly, reexamine the approach, and not push too hard (Seidel, Ball, Dains, et al., 2011). Empathy is the capacity to understand what another person is experiencing from within that person’s frame of reference; it is often described as the ability to put oneself in another’s shoes. The essence of empathic interaction is accurate understanding of another’s feelings (Mathiasen, 2006). Empathy differs from sympathy, which is having feelings or emotions similar to those of another person, rather than understanding those feelings (Mathiasen, 2006). Unprepared parents can be disturbed by many normal developmental changes, such as a toddler’s diminished appetite, negativism, altered sleeping patterns, and anxiety toward strangers. The chapters on health promotion provide the nurse information for counseling parents. However, anticipatory guidance should extend beyond giving general information during brief visits to empowering families to use the information as a means of building competence in their parenting abilities (Magar, Dabova-Missova, and Gjerdingen, 2006). To achieve this level of anticipatory guidance, the nurse should: A number of blocks to communication can adversely affect the quality of the helping relationship. The interviewer introduces many of these blocks, such as giving unrestricted advice or forming prejudged conclusions. Another type of block occurs primarily with the interviewees and concerns information overload. When individuals receive too much information or information that is overwhelming, they often demonstrate signs of increasing anxiety or decreasing attention. Such signals should alert the interviewer to give less information or to clarify what has been said. Box 29-2 lists some of the more common blocks to communication, including signs of information overload. Sometimes communication is impossible because two people speak different languages. In this case it is necessary to obtain information through a third party, the interpreter. When using an interpreter, the nurse follows the same interviewing guidelines. Specific guidelines for using an adult interpreter are given in the Guidelines box. Communicating with families through an interpreter requires sensitivity to cultural, legal, and ethical considerations (see Cultural Competence box). For example, in some cultures, using a child as an interpreter is considered an insult to an adult because children are expected to show respect by not questioning their elders. In some cultures, class differences between the interpreter and the family may cause the family to feel intimidated and less inclined to offer information. Therefore it is important to choose the translator carefully and provide time for the interpreter and family to establish rapport. Active attempts to make friends with children before they have had an opportunity to evaluate an unfamiliar person tend to increase their anxiety. Continue to talk to the child and parent but go about activities that do not involve the child directly, thus allowing the child to observe from a safe position. If the child has a special toy or doll, “talk” to the doll first. Ask simple questions such as “Does your teddy bear have a name?” to ease the child into conversation. Other guidelines for communicating with children are in the Guidelines box. Specific guidelines for preparing children for procedures, a common nursing function, are in Chapter 39. The normal development of language and thought offers a frame of reference for communicating with children. Thought processes progress from sensorimotor to perceptual to concrete and finally to abstract, formal operations. An understanding of the typical characteristics of these stages provides the nurse with a framework to facilitate social communication (Box 29-3). Everything is direct and concrete to small children. They are unable to work with abstractions and interpret words literally. Analogies escape them because they are unable to separate fact from fantasy. For example, they attach literal meaning to such common phrases as “two-faced,” “sticky fingers,” or “coughing your head off.” Children who are told they will get “a little stick in the arm” may not be able to envision an injection (Fig. 29-3). Therefore avoid using a phrase that might be misinterpreted by a small child. Another dilemma in interviewing adolescents is that two views of a problem frequently exist—the teenager’s and the parents’. Clarification of the problem is a major task. However, providing both parties an opportunity to discuss their perceptions in an open and unbiased atmosphere can, by itself, be therapeutic. Demonstrating positive communication skills can help families communicate more effectively (see Guidelines box). Box 29-4 describes both verbal and nonverbal techniques. Because of the importance of play in communicating with children, play is discussed more extensively in the section that follows. Any of the verbal or nonverbal techniques can give rise to strong feelings that surface unexpectedly. Be prepared to handle them or to recognize when issues go beyond your ability to deal with them. At that point, consider an appropriate referral.

Communication, History, and Physical Assessment

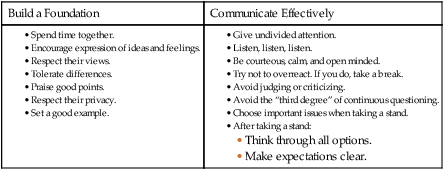

Guidelines for Communication and Interviewing

Establishing a Setting for Communication

Appropriate Introduction

Assurance of Privacy and Confidentiality

Computer Privacy and Applications in Nursing

Telephone Triage and Counseling

Communicating with Families

Communicating with Parents

Listening and Cultural Awareness

Using Silence

Being Empathic

Providing Anticipatory Guidance

Avoiding Blocks to Communication

Communicating with Families Through an Interpreter

Communicating with Children

Communication Related to Development of Thought Processes

Early Childhood.

Adolescence.

Communication Techniques

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Communication, History, and Physical Assessment

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access