Cognitive Disorders

In older people, the development of delirium or acute confusion…has been associated with increased lengths of hospital stay, the need for chemical and physical restraints, readmission, and increased mortality.

The death of the mind is the worst death imaginable, and for millions of Americans the slow death…creates a world of pain and suffering. The number of affected individuals signal[s] the profound magnitude of the public health challenges to our society.

Time is the most precious gift in our possession, for it is the most irrevocable.

—Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906–1945)

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Discuss the changes that occur in the aging brain.

Describe the four distinct, yet mutually interacting, memory systems identified by Heindel and Salloway.

Discuss the latest research findings related to the etiology of dementia of the Alzheimer’s type.

Compare and contrast the etiology of vascular dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies.

Distinguish the clinical symptoms of delirium, dementia, and amnestic disorders.

Describe the onset and course of dementia from early to terminal stages.

Explain the rationale for use of the Wong-Baker Faces Rating Scale, NEECHAM Confusion Scale, and Agitated Behavior in Dementia Scale when assessing clients with cognitive disorders.

Articulate the importance of identifying a client’s cultural and educational background during the assessment process.

Describe the elements of a comprehensive history and physical examination for a client who exhibits clinical symptoms of dementia of the Alzheimer’s type.

Formulate nursing interventions for a client with the diagnosis of delirium who exhibits agitated and aggressive behavior.

Develop an educational program to use with family members of clients with the diagnosis of dementia.

Key Terms

Agnosia

Anterograde amnesia

Aphasia

Apraxia

Asterixis

Binswanger’s disease

Cognition

Cognitive disorder

Confabulation

Delirium

Dementia

Dementia with Lewy bodies

Disturbances in executive functioning

Dysgraphia

Dysnomia

Perseveration

Retrograde amnesia

Sundown syndrome

Cognition refers to the mental processes of comprehension, judgment, memory, and reasoning in contrast to emotional and volitional (willful or free-will) processes (Shahrokh & Hales, 2003). A cognitive disorder occurs when there is a clinically significant deficit in cognition from a previous level of functioning. Although cognitive disorders are the most prevalent psychiatric disorders occurring in later life, they can occur at any time. At least 70 known cognitive disorders are caused by intracranial or primary diseases of the central nervous system (eg, epilepsy, brain trauma, infection) and extracranial diseases or diseases of other organ systems (eg, drug intoxication, poisons, systemic infections). Cognitive impairment ranges from irreversible to fully reversible, depending on the contributing factor. One half of the beds in community long-term care facilities contain clients with the diagnosis of dementia. Other cognitive disorders, such as delirium and amnestic disorders, also consume large amounts of public health resources. As the United States population increases and ages, more older adults will be diagnosed with cognitive deficits such as delirium, dementia, or amnesia (Peskind & Raskind, 1996; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

In the hospital setting, delirium is a frequent problem. In the primary care setting, dementia has become a common ailment. In some cases, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is diagnosed prematurely and incorrectly. Amnesia may occur at any age, depending on the primary pathological process (eg, traumatic brain injury, stroke, exposure to toxic substances).

This chapter discusses the major cognitive disorders and their subtypes, when applicable, as identified by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000). Cognitive disorders secondary to substance-related disorders are included in the classifications but are discussed fully in Chapters 25 and 32. According to criteria established by the DSM-IV-TR, the differential diagnosis of each disorder is based on the type of onset and course of symptoms. Mental processes, speech, behavior, and level of consciousness, as well as presumed or established etiology, are considered in determining a diagnosis (APA, 2000).

History of Dementia

Dementia was first described in a book about mental illness in 1838. In 1894, Dr. Alois Alzheimer, a German neuropathologist who had a particular interest in “nervous disorders,” described changes in the brain caused by vascular disease (now known as vascular dementia). In 1901, he treated a middle-aged woman who had exhibited clinical symptoms of memory loss, disorientation, “peculiar behavior,” anxiety, and hallucinations. When the woman died in 1906 as a result of multiple causes, including pneumonia and nephritis, Dr. Alzheimer was unable to classify the disease into any existing category. A postmortem examination of the brain revealed microscopic and macroscopic lesions and distortions, including neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. The woman’s neurologic changes were identified as AD (dementia of the Alzheimer’s type [DAT]) (E-MentalHealth.com, 2005; Needham, 2006).

The clinical symptoms of dementia were attributed to the aging process until the 1970s when researchers determined that dementia was caused by several factors such as organic change, disease process, or neurochemical deficiency within the brain. This discovery enabled researchers to develop a classification of the various types of dementia now included in the DSM-IV-TR.

Cognitive Function

The brain integrates, regulates, initiates, and controls functions in the entire body. The processes of thinking, remembering, and learning occur in different areas of the brain. For example, the frontal lobe organizes and classifies information; the parietal lobe processes sensory input; the temporal lobe synthesizes auditory, visual and somatic input into thought and memory; and the occipital lobe controls visual information that is received and processed through the retina (Needham, 2006).

Research has been done to determine the effects of aging on the brain and cognitive function. Figure 27-1 illustrates the major areas of the brain involved in cognitive functions. Some findings include the following:

The normal human brain weighs approximately 1,350 grams and declines approximately 7% to 8% in weight as one ages.

Cell loss is not uniform because the frontal lobes degenerate at a faster rate than the other lobes.

Gray matter is lost at a greater rate initially, but white matter loss disproportionately increases as one ages.

Ventricular size increases with age.

Approximately 50% of aging individuals experience atherosclerosis in cerebral vessels.

Changes in neurotransmitter function occur, such as alterations in neurotransmitter concentration, receptor density, and functional activity (Salloway, 1999).

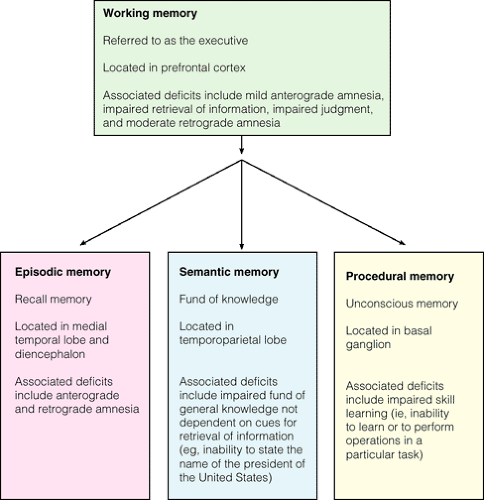

Results also demonstrate that intellect peaks at age 30 years, plateaus at ages 50 to 60 years, and then slowly declines until the age of 70 years. Decline of intellect accelerates as one’s age nears 80 years (Salloway, 1999). According to neuropsychological investigative studies of brain-injured clients by Heindel and Salloway (1999), results demonstrate convincingly that memory is not a single homogeneous entity. Rather it is composed of four distinct, yet mutually interacting, memory systems: working memory, episodic memory, semantic memory, and procedural memory. Figure 27-2 illustrates the different memory systems and their locations, including examples of the specific types of memory impairment. Understanding these systems provides a powerful clinical tool for assessing cognitive disorders in clients.

Etiology of Cognitive Disorders

Studies regarding the etiology of delirium and amnestic disorders have focused almost exclusively on biologic factors. Various theories have been proposed to

suggest the etiology of dementia, diseases associated with dementia, and amnestic disorders.

suggest the etiology of dementia, diseases associated with dementia, and amnestic disorders.

Etiology of Delirium

Delirium is defined as a transient cognitive disorder, usually acute or subacute in onset, presenting as a reversible global dysfunction in cerebral metabolism. It is usually caused by disturbance of brain pathology by a medical disorder or an ingested substance. Delirium is considered a syndrome (ie, a group of signs and symptoms that cluster together), not a disease, that has many causes.

The three major causes are central nervous system diseases (eg, epilepsy, meningitis, encephalitis), systemic illnesses (eg, heart failure or pulmonary insufficiency), and either drug intoxication or withdrawal from pharmacologic or toxic agents. For example, any drug taken by a client has the potential to precipitate delirium secondary to adverse effects.

Other causes of delirium include endocrine or metabolic disorders (eg, hypoadrenocorticism or hypercalcemia) and deficiency diseases (eg, thiamine, nicotinic acid, folic acid). In addition, systemic infections, electrolyte imbalance, postoperative states, and traumatic injury to the head or body also are associated with causing delirium (APA, 2000; Peskind & Raskind, 1996; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Etiology of Dementia

Dementia refers to a syndrome of global or diffuse brain dysfunction characterized by a gradual, progressive, chronic deterioration of intellectual function. The

persistent and stable nature of the impairment distinguishes it from the altered levels of consciousness and fluctuating deficits of delirium. Dementia has many causes. Until recently, the majority of cases were considered to be of two main types: dementia of the Alzheimer’s type and vascular dementia. Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a form of dementia that shares characteristics of both DAT and Parkinson’s disease. It is now thought to account for 10% to 15% of all dementia cases in older people. Furthermore, up to 40% of clients with DAT also have concomitant DLB (DLB-DAT) (Peskind & Raskind, 1996; Sadock & Sadock, 2003; Newsline, 2004; Alzheimer’s Society, 2006).

persistent and stable nature of the impairment distinguishes it from the altered levels of consciousness and fluctuating deficits of delirium. Dementia has many causes. Until recently, the majority of cases were considered to be of two main types: dementia of the Alzheimer’s type and vascular dementia. Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a form of dementia that shares characteristics of both DAT and Parkinson’s disease. It is now thought to account for 10% to 15% of all dementia cases in older people. Furthermore, up to 40% of clients with DAT also have concomitant DLB (DLB-DAT) (Peskind & Raskind, 1996; Sadock & Sadock, 2003; Newsline, 2004; Alzheimer’s Society, 2006).

Etiology of Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type (DAT)

The search for the causes and treatment of DAT continues. Several theories exist. A complete discussion of these theories is beyond the scope of this chapter. However, current theories regarding the causes of dementia are cited below and include:

The apolipoprotein theory focuses on the build up of apolipoprotein deposits or plaques in the brain. Genetic screening, based on this theory, is now available to determine an individual’s apolipoprotein E genotype, revealing genetic risk information to asymptomatic individuals (Wachter, 2006).

The beta-amyloid protein theory postulates that symptoms of DAT are the result of neuronal degeneration due to the neurotoxic properties of these proteins (Peskind & Raskind, 1996; Medina, 2001; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

The genetic theory, which proposes a genetic link to DAT, which focuses on three genes on three separate chromosomes (1, 14, and 21).

The immune system theory suggests that DAT is the result of immune system malfunctions.

The oxidation theory states that the buildup of damage from oxidative processes in neurons results in the loss of various body functions.

The virus and bacteria theory proposes that DAT may be caused by a viral- or bacterial-induced condition secondary to the breakdown of the immune system (eg, herpes virus).

The nutritional theory postulates that poor nutrition and lack of mental stimulation during childhood may predispose one to DAT later in life.

The metal deposit theory speculates that an accumulation of aluminum ions replacing iron ions may contribute to existing dementia.

The neurotransmitter theory hypothesizes that DAT is caused by a decrease in acetylcholine, dopamine, norepinephrine, or serotonin levels, limiting neuronal activity. A second theory postulates that excessive stimulation of glutamate damages neurons.

The membrane phospholipid metabolism theory proposes that DAT is caused by an abnormality in metabolism that causes neuronal cell membranes to be less fluid or more rigid than normal.

Researchers continue to work diligently to determine the cause of DAT and proposed treatments. Neuroimaging has been used in the diagnostic evaluation of clients with memory and cognitive impairment. The predominant finding of bilateral posterior temporal and parietal perfusion defects is thought to be highly predictive of DAT.

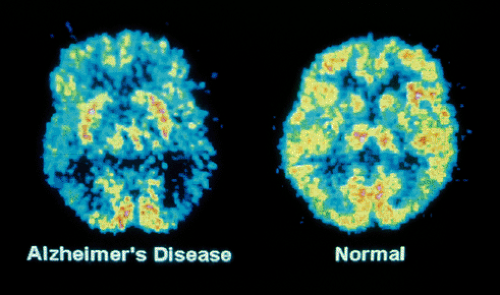

Computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scans show atrophy and lowered blood flow and energy consumption in the brains of clients with DAT. Deterioration appears first in the superior parietal cortex, the temporal lobes, and the hippocampus. In late stages, atrophy is severe (Figure 27-3). At present, brain imaging can distinguish early DAT fairly well from depression but not always from other brain diseases. Microscopic findings (postmortem) show senile plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, neuronal loss, synaptic loss, and granulovascular degeneration of neurons (Holman & Devous, 1992; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Etiology of Dementia With Lewy Bodies (DLB)

DLB is difficult to clinically differentiate from DAT. Both dementias indicate cognitive decline inappropriate to age that interferes with normal tasks of daily living.

Research studies have found that dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is caused by neurohistologic changes (spherical protein deposits in nerve cells) in the cerebral cortex and other areas of the brain. Their presence in the brain disrupts the brain’s normal functioning, interrupting the action of important chemical messengers, including acetylcholine and dopamine. When lesions collect in the substantia nigra of the

brain stem, they cause Parkinson’s disease. Researchers have found that Lewy bodies never form in normal brains (Newsline, 2004; Sylvester, 2004).

brain stem, they cause Parkinson’s disease. Researchers have found that Lewy bodies never form in normal brains (Newsline, 2004; Sylvester, 2004).

Etiology of Vascular Dementia

Vascular dementia is thought to result from infarction of small- and medium-sized cerebral vessels causing parenchymal lesions to occur over wide areas of the brain. Plaques or thromboemboli from distant organs such as heart valves are presumed to be the cause of the infarction. Binswanger’s disease is a type of vascular dementia that is characterized by the presence of many small infarctions affecting the white matter of the brain that spare the cortical regions (Peskind & Raskind, 1996; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Etiology of Diseases Associated with Dementia

Several diseases are often associated with dementia (APA, 2000; Busse & Blazer, 1996; Sadock & Sadock, 2003). They include:

Familial multiple system taupathy (eg, a buildup of tau protein in the neurons and glial cells) occurring in individuals in their forties or fifties; thought to be carried on chromosome 17 and shares some brain abnormalities with DAT; often referred to as presenile dementia.

Pick’s disease, progressive disorder of middle and late life characterized by atrophy and microscopic changes of the frontotemporal regions; difficult to differentiate from DAT.

Parkinson’s disease due to the presence of neurohistologic lesions in the basal ganglia; associated impairment of cognitive abilities; commonly associated with dementia.

Etiology of Amnestic Disorders

Amnestic disorders are described as the acquired impaired ability to learn and recall new information or to recall previously learned information. The etiology of an amnestic disorder is usually damage to diencephalic and medial temporal lobe structures, important in memory functions (Peskind & Raskind, 1996). The causes of amnestic disorders may be many, and are typically classified as medical conditions such as thiamine deficiency and hypoglycemia; primary brain conditions such as head trauma; and substance-related disorders such as those involving alcohol and neurotoxins (APA, 2000; Sadock & Sadock, 2003). Alcohol-induced

persisting amnestic disorder is discussed in Chapter 25, Substance-Related Disorders.

persisting amnestic disorder is discussed in Chapter 25, Substance-Related Disorders.

Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Characteristics of Cognitive Disorders

Differentiating delirium from dementia or depression is challenging. It would be easier if a client developed only one syndrome at a time. Unfortunately, this is not always the case, because clients can actually suffer from all three syndromes at once. Many of the clinical symptoms overlap, requiring a thorough investigation during the assessment process (Table 27-1).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The diagnostic characteristics of cognitive disorders described here help to clarify difference among delirium, dementia, and depression. Although depression was discussed in detail in Chapter 21, reference is made to depression in this chapter to compare and contrast clinical symptoms with those of delirium and dementia.

Delirium

Delirium is one of the most common and, by far, one of the most life-threatening psychiatric illnesses. Several terms may be used to identify delirium, including ICU (intensive care unit) psychosis, encephalopathy, acute brain failure, and acute confusional state.

Clinical symptoms include a rapid onset with symptoms varying sharply in a short period. Judgment may be impaired. Affect or mood fluctuates. Memory of recent events is impaired. Disorientation to person and place usually occurs. Dysnomia, the inability to name objects, and dysgraphia, the impaired ability to write, may occur. Speech may be incoherent, sparse, or fluent. Perceptual disturbances may include misinterpretations, illusions, or hallucinations. Thought processes appear confused, with possible delusional content.

Behavior exhibited may include agitation, restlessness, wandering, and disturbance in sleep–wake cycle. Asterixis, an abnormal movement in which the client exhibits a peculiar flapping movement of hyper-extended hands, is seen in various delirious states. Hypoactive symptoms, such as lethargy and reduced psychomotor activity, are common but less frequently identified.

Although the client may perform poorly on mental status examinations, cognitive ability generally improves when the client recovers, unless the delirium is superimposed on moderate to severe dementia. The prognosis includes a return to premorbid function if the cause is corrected in time.

High-risk populations include the following individuals: those who take numerous medications that may interact and cause adverse reactions; persons who undergo age-related physiologic changes that reduce cerebral reserve capacity and limit the ability to tolerate stressors; individuals with inefficient homeostatic and immune mechanisms; persons with impaired hepatic function or reduced renal excretion; and those who are drug dependent (Branski, 1998; Radovich, 1999).

The incidence of delirium in hospitalized individuals older than 65 years is approximately 10% to 15% at the time of admission; another 10% to 40% may develop delirium while in the hospital. Approximately 40% to 50% of clients recovering from surgery for a hip fracture exhibit clinical symptoms of delirium. The highest rate is exhibited by clients after cardiotomy. Additionally, delirium is seen frequently in individuals who relocate from the hospital to rehabilitation centers or long-term care facilities, especially when the length of hospital stay is less than 3 or 4 days and the client has not fully responded to medical or nursing interventions (APA, 2000; Peskind & Raskind, 1996; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Delirium Due to a General Medical Condition

The diagnosis Delirium Due to a General Medical Condition is given when findings indicate that the cognitive disturbance is the direct physiologic consequence of a general medical condition such as a urinary tract infection (see Clinical Example 27-1), respiratory tract infection, septicemia, or end-stage renal disease.

Certain focal lesions of the right parietal lobe and occipital lobe also may cause delirium. Other causes include metabolic disorders, fluid or electrolyte imbalances, hepatic disease, thiamine deficiency, postoperative states, hypertensive encephalopathy, and sequelae of head injury (APA, 2000; Peskind & Raskind, 1996).

Substance-Induced Delirium

Clinical symptoms of substance-induced delirium occur within minutes to hours after taking relatively

high doses of certain drugs. The delirium resolves as the substance is discontinued or eliminated from the body. Substances and medications reported to cause delirium include anesthetics, analgesics, antihistamines, anticonvulsants, anti-asthmatic agents, antiparkinsonism drugs, corticosteroids, and muscle relaxants. Antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents also have been identified as causes of delirium in the elderly (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

high doses of certain drugs. The delirium resolves as the substance is discontinued or eliminated from the body. Substances and medications reported to cause delirium include anesthetics, analgesics, antihistamines, anticonvulsants, anti-asthmatic agents, antiparkinsonism drugs, corticosteroids, and muscle relaxants. Antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents also have been identified as causes of delirium in the elderly (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Clinical Example 27.1: The Client With Delirium Due to a Urinary Tract Infection

LS, a 65-year-old retired mechanic, had just been transferred to a rehabilitation center from a local hospital after surgical repair of a fractured hip. During hospitalization, he had an indwelling Foley catheter in place. The catheter was removed 2 days after surgery. On the fifth postoperative day, LS began to exhibit agitation and complained of seeing animals in his room. He also expressed a concern that someone was going to hurt him. He was oriented to person only. At night, LS attempted to crawl out of bed over the side rails. During the day, he appeared to be aware of his surroundings and was able to make his needs known. He had no recall of the episodic confusion or disorientation he exhibited. The result of a urinalysis with culture and sensitivity revealed a urinary tract infection due to Escherichia coli. LS was exhibiting clinical symptoms of delirium that resolved after a 10-day course of treatment with Bactrim.

Delirium Due to Multiple Etiologies

This diagnosis is used to alert clinicians to the common situation in which the delirium has more than one etiology. For example, a 55-year-old male who undergoes coronary artery bypass surgery may exhibit clinical symptoms of delirium secondary to anesthesia, pain medication, antibiotics, and environmental stimuli secondary to high-tech equipment in the recovery room.

Delirium, Not Otherwise Specified

This diagnosis refers to delirium that does not meet criteria for any specific type of delirium. There is insufficient evidence to establish a specific etiology.

Dementia

Dementia is characterized by impaired judgment, orientation, memory, attention, and cognition (JOMAC), which are affected either by a pattern of simple, gradual deterioration or by rapid, complicated deterioration. Impaired judgment, or the inability to make reasonable decisions, is one of the earliest signs of dementia. It may occur during business dealings or social functions; for example, the person engages in a reckless business venture or displays a disregard for conventional rules of social conduct.

Disorientation to person, place, and time is one of the most common signs of brain dysfunction. An individual becomes more disoriented as the impairment becomes more extensive. A person with minimal impairment may misjudge the date by weeks or months. Moderate impairment generally involves confusion about geographic location such as city or state as well as time, whereas severe impairment is demonstrated by disorientation with respect to time, place, and person. Short-term memory, attention, and concentration deficits are observable in this disorder because the person loses his or her train of thought, forgets what was said just a few minutes earlier, and may be unable to repeat the information just communicated (Peskind & Raskind, 1996; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Other characteristics or associated features include confabulation, perseveration, concrete thinking, and emotional lability. Confabulation is the filling in of memory gaps with false but sometimes plausible content to conceal the memory deficit. Perseveration is the inappropriate continuation or repetition of a behavior such as giving the same details over and over even when told one is doing so. Abstraction skills are impaired; therefore, the person tends to think in concrete terms. The tendency to manifest rapid, inappropriate, exaggerated mood swings often occurs, and marked anxiety or depression may be seen in mild cases.

Personality changes are often seen in clients with dementia. The normally active person may become withdrawn and apathetic when social involvement narrows.

Psychotic or behavioral disturbances such as agitation, wandering, hallucinations, delusions, suspiciousness, reversal of sleep–wake pattern, inappropriate sexual behavior, hostility, aggressiveness, and combativeness may occur.

Clients with dementia often seem to exhibit increased confusion, restlessness, agitation, wandering, or combative behavior in the late afternoon and evening hours. This phenomenon, referred to as the sundown syndrome, may be due to a misinterpretation of the environment, lower tolerance for stress at the end of the day, or overstimulation due to increased environmental activity later in the day. Clients may also exhibit a reversal in their sleep pattern, sleeping during the day and staying awake during the night (APA, 2000; Peskind & Raskind, 1996; Sadock & Sadock, 2003

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access