Case Management

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

1. Define continuity of care, care management, case management, and advocacy.

2. Describe the scope of practice, roles, and functions of a case manager.

3. Compare and contrast the nursing process with processes of case management and advocacy.

4. Identify methods to manage conflict, as well as the process of achieving collaboration.

5. Define and explain the legal and ethical issues confronting case managers.

Key Terms

advocacy, p. 495

affirming, p. 497

allocation, p. 498

amplifying, p. 496

assertiveness, p. 499

autonomy, p. 502

beneficence, p. 502

brainstorming, p. 498

care management, p. 485

care maps, p. 491

case management plans, p. 490

case manager, p. 491

clarifying, p. 496

collaboration, p. 499

cooperation, p. 499

coordinate, p. 487

critical pathways, p. 485

demand management, p. 485

disease management, p. 485

distributive outcomes, p. 499

information exchange process, p. 496

informing, p. 496

integrative outcomes, p. 499

justice, p. 502

life care planning, p. 492

negotiating, p. 499

nonmaleficence, p. 502

population management, p. 484

problem-purpose-expansion method, p. 498

problem solving, p. 498

risk sharing, p. 491

social mandate, p. 484

supporting, p. 497

utilization management, p. 485

veracity, p. 502

verifying, p. 497

—See Glossary for definitions

Ann H. Cary, PhD, MPH, RN, A-CCC

Ann H. Cary, PhD, MPH, RN, A-CCC

Dr. Ann H. Cary began practicing public health nursing in the 1970s as a home-health nurse in New Orleans, Louisiana, where she executed case management functions daily. She has served on national workgroups that established the standards of practice for case managers, created certification examinations for case managers, authored numerous articles on case management issues, taught baccalaureate and graduate-level courses in case management, and directed graduate programs in case management and continuity of care. She is the Director of the School of Nursing at Loyola University New Orleans. In New Orleans, she also serves on a variety of foundation and community boards whose missions are to increase access, coordinated care, and quality delivery for their clients.

The health care industry comprises systems that attempt to integrate financing, management, and delivery of services. Challenges abound for clients and providers as they attempt to coordinate care, transition clients among providers and systems, access documentation about clients, communicate with each information system of the provider, and navigate the complexity of values to optimize quality and access while holding or reducing costs. Delivery of care may occur through a network of providers, such as negotiated contracts with hospitals, physicians, nurse practitioners, pharmacies, ancillary health services, and outpatient centers. Managing the health of populations served by the integrated systems is essential. Population management includes wellness and health promotion, illness prevention, acute and subacute care, rehabilitation, end-of-life care, and care coordination. Examples include planning strategies for adolescents in a school system or the elderly in a community (Huber, 2010). The use of integrated systems has had the following important consequences on the focus of care (AHA, 2003-2004):

• Care management services and programs provide access and accountability for the continuum of health.

The contemporary focus of integrated health systems defines the nature of the client as a population rather than as an individual. In these systems, population management involves the following activities:

• Creating benefits and network designs to address these needs

• Prioritizing actions to produce a desired outcome with available resources

• Deploying case managers within a variety of delivery and insurance systems to clients and providers

Establishing a relationship between financing, managing, delivering, and coordinating services is critical to reach the goal of population management—that is, achieving healthy outcomes at the population level. The Healthy People 2020 goals are to increase both quality of life and years of healthy life, to achieve health equity and eliminate health disparities, and to create social and physical environments as a social mandate for health care. In the second decade of the twenty-first century, case management will be an intervention of choice to positively influence the leading health indicators and focus areas of Healthy People 2020.

Establishing evidence-based strategies is critical to the success of case management for individuals and populations. Using the current best evidence blended with clinical expertise is a critical skill of the case manager (Allison, 2004; CMSA, 2010). In their practice, nurse case managers have the following core values: increasing the span of healthy life, reducing disparities in health among Americans, and promoting access to care and to preventive services. Many of the interventions nurses use with clients and health care systems will further the Healthy People 2020 objectives. These include case management interventions to minimize fragmentation and promote quality transitions of care; incorporate standardized practice tools and adherence guidelines; improve safety of care; and use interprofessional teams to deliver services.

In the Intervention Wheel model for public health nursing practice, the nursing actions of case management, collaboration, and advocacy comprise 3 of 16 evidence-based interventions for individuals, families, and populations served by public health nurses (Keller et al, 2004). These three concepts and practice arenas for public health nurses are more fully described in this chapter.

Definitions

Care management is a health care delivery process that helps achieve better health outcomes by anticipating and linking clients with the services they need more quickly (CMSA, 2010). It is an enduring process in which a population manager establishes systems and processes to monitor the health status, resources, and outcomes for a targeted aggregate of the population. The population manager is the tactical architect for a population’s health in the delivery system. Building blocks that are used by the manager include risk analysis; data mapping; monitoring for health processes, indicators, and unexpected illnesses; epidemiological investigation of unexpected illnesses; development of multidisciplinary action plans and programs for the population; and identifying case management triggers or events (e.g., when dramatic results are obtained by prevention or early intervention) that indicate the need for early referrals of high-risk clients (Haag and Kalina, 2005).

Care management strategies were initially developed by health maintenance organizations (HMOs) in the late 1970s to manage the care of different populations. The purpose was to promote quality and ensure appropriate use and costs of services. Typically these involved clients with reduced self-care capacity and whose diseases and treatments were intense (Michaels and Cohen, 2005). Care management strategies include utilization management, critical pathways, case management, disease management, and demand management. Utilization management attempts to promote optimal use of services to redirect care and monitor the appropriate use of provider care/treatment services for both acute and community/ambulatory services. Providers are offered multiple options for care with different economic implications. Through the use of utilization management, clients who have repetitive readmissions (i.e., they fail to respond to care) are often referred to care management programs. Critical pathways and maps, which were more popular in the early 2000s, are tools that specify activities providers may use in a timely sequence to achieve desired outcomes for care. The outcomes are measurable, and the pathway tools strive to reduce differences in client care. Today, agencies are more likely to use clinical paths, evidence-based practice protocols or guidelines, or case management plans of care. Case management services are used for clients with specific diagnoses who may have high-use patterns, non-compliance issues, cost caps (e.g., no more than $10,000 to $20,000 can be spent on their case), or threshold expenses.

Disease management constitutes systematic activities to coordinate health care interventions and communications for populations with conditions in which client self-care efforts are significant (CMSA, 2010). For example, diabetes, asthma, and depression are typically targeted by providers and insurers. These programs have evolved largely as initiatives in managed care organizations (Huber, 2010).

Demand management seeks to control use by providing clients with correct information and education strategies to make healthy choices, to use healthy and health-seeking behaviors to improve their health status, and to make fewer demands on the health care system (Tufts Managed Care Institute, 2011).

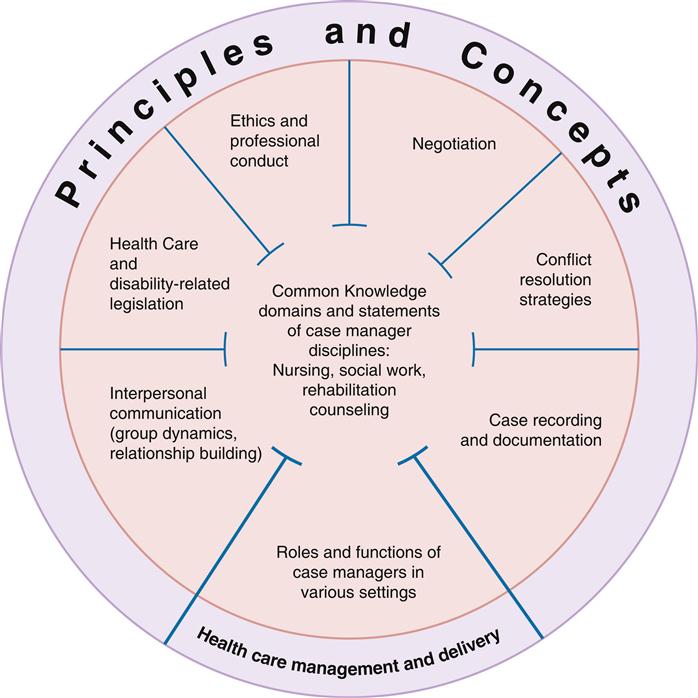

In contrast, case management comprises the activities implemented with individual clients in the system. The case manager builds on the basic functions of the traditional nurse’s role and adapts new competencies for managing transitions from health care facility to home, such as wellness and prevention, and interprofessional teams). Case management is the single most frequent intervention reported by 91% of staff public health nurses (Grumbach et al 2004). Case management is provided by the disciplines of nursing, social work, and rehabilitation counseling, to name a few. Research by Park, Huber, and Tahan (2009) found that common knowledge exists for case management providers from the disciplines of nursing, social work, and rehabilitation counseling: case recording and documentation, conflict resolution strategies, negotiation, ethics, relevant legislation, interpersonal communication, and roles and functions required in various settings. Figure 22-1 illustrates the unified knowledge domains for professionals in case management and emphasizes the fluidity of common knowledge used by case managers regardless of discipline. In addition, case managers in case-management programs are expanding their clinical expertise to embrace the process of disease management, a successful strategy for population outcomes. Specialty case management in advanced nursing practice is a critical role in this field (Cohen and Cesta, 2005). In implementing case management, these nurses work with clients or community aggregates as well as systems managing disease and outcomes, whereas nurses with bachelor’s degrees more often focus on care at the individual level (Stanton and Dunkin, 2002).

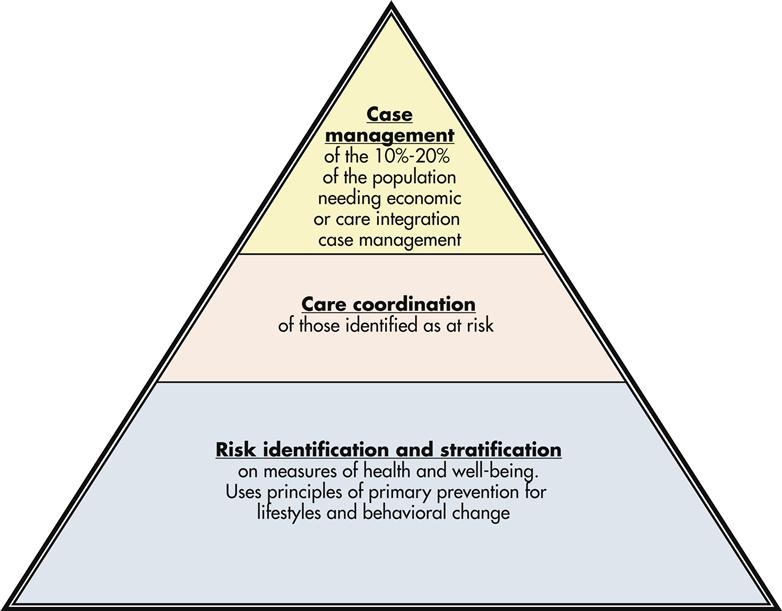

This chapter describes the nature and process of case management for individual and family clients. Case management has a rich tradition in public health nursing and is frequently found in hospitals, transitional and long-term care, home and hospice care, and health insurance companies. Case management is at the top of the care management pyramid, reserved for a subset of the population. In Figure 22-2 Coggeshall (2008) illustrates a case management model pyramid that recognizes the tenets of risk stratification and case finding, coordination, and ultimately case management of a smaller proportion of clients in the population. This model recognizes the interchange of public health and populations at risk for service intensity resulting from economic or care integration needs.

Concepts of Case Management

Reviewing multiple or historical definitions of case management helps to demonstrate the complex process and the concept of case management over time. Weil and Karls, in 1985, described case management as a “set of logical steps and process of interacting within a service network which ensures that a client receives needed services in a supportive, effective, efficient and cost-effective manner” (p 4). Case management was defined by the American Hospital Association (1986) as the process of planning, organizing, coordinating, and monitoring services and resources needed by clients, while supporting the effective use of health and social services. Secord (1987) defined case management as a systematic process of assessing, planning, and coordinating the service, referrals, and monitoring that meets the multiple needs of clients. Bower (1992) described the continuity, quality, and cost-containment aspects of case management as a health care delivery process, whose goals are to provide quality health care, decrease fragmentation, enhance the client’s quality of life, and contain costs. A focus on collaboration is important in the National Case Management Task Force definition. The definition emphasizes a collaborative process between the case manager, the client, and representatives of other agencies and provider groups. The process includes assessments, plans, implementation, coordination, monitoring and the evaluation of the options and services to meet an individual’s health needs. Effective communication is essential to identify available resources to promote quality, cost effective outcomes (CMSA, 2010; Mullahy, 2010).

As a competency, case management was defined in the public health nursing literature as the “ability to establish an appropriate plan of care based on assessing the client/family and coordinating the necessary resources and services for the client’s benefit” (Muller and Flarery, 2003, p 230). Knowledge and skills required to achieve this competency include the following:

• Knowledge of community resources and financing mechanisms

• Written and oral communication and documentation

• Proficient negotiating and conflict-resolving practices

• Application of evidence-based practices and outcomes measures

In the latest Standards of Practice for Case Management, case management is defined as “a collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation, care coordination, evaluation and advocacy for options and services to facilitate an individual’s and family’s comprehensive health needs through communication and available resources to promote quality cost-effective outcomes” (CMSA, 2010, p 24).

Case management practice is complex as evidenced by the need to coordinate activities of multiple providers, payers, and settings throughout a client’s continuum of care. For example, in a contemporary model of primary care practice, the medical home provides accessible, continuous, coordinated, comprehensive care and is managed centrally by a physician with the active involvement of non-physician practice staff. Care provided must be assessed, planned, implemented, adjusted, and evaluated on the basis of goals designed by many disciplines as well as goals of the client, the family, significant others, and community organizations. Although likely employed and located in one setting, the nurse as case manager will be influencing the selection and monitoring of care provided in other settings by formal and informal care providers. With the increased use of electronic care delivery through telehealth activities, case management activities are now handled via telephone, e-mail, and fax, and through video visits and electronic monitoring in a client’s residence. Case managers may also deliver care to a global network of clients located in different countries. A challenging problem is the fragmentation of services, which can result in overuse, underuse, gaps in care, and miscommunication. This can result in costly client outcomes and quality issues in hand-offs and transitions from provider to provider.

Case management differs between urban and rural settings. In the rural setting, where the distance between populations is more expansive, there are fewer organized community-based systems and communication and distance is often a greater challenge. Furthermore, the economics, pace and style of life, values, and social organization all differ. In a study by Stanton and Dunkin (2002) and later referenced in 2009 (Stanton and Dunkin), rural residents identified four barriers to access to care that confront case managers in rural areas: lack of proximity to providers, limited services, scarcity of providers, and availability of emergency and acute care services. Transportation, both for nurses and for clients, and lack of health insurance and benefits were documented challenges to rural clients of case managers. These issues were also identified by Waitzkin, Williams, and Bock (2002) as problems for rural clients in managed care systems. In a 2009 study, Stanton and Dunkin identified the need for safety during transitional care and by the nurse case managers. Specific actions included the need for effective communication, medication reconciliation during transitions, and coordination of care among multiple providers for rural clients in a rural nurse-managed clinic. These actions are essential to support The Joint Commission’s National Safety Goals (2009).

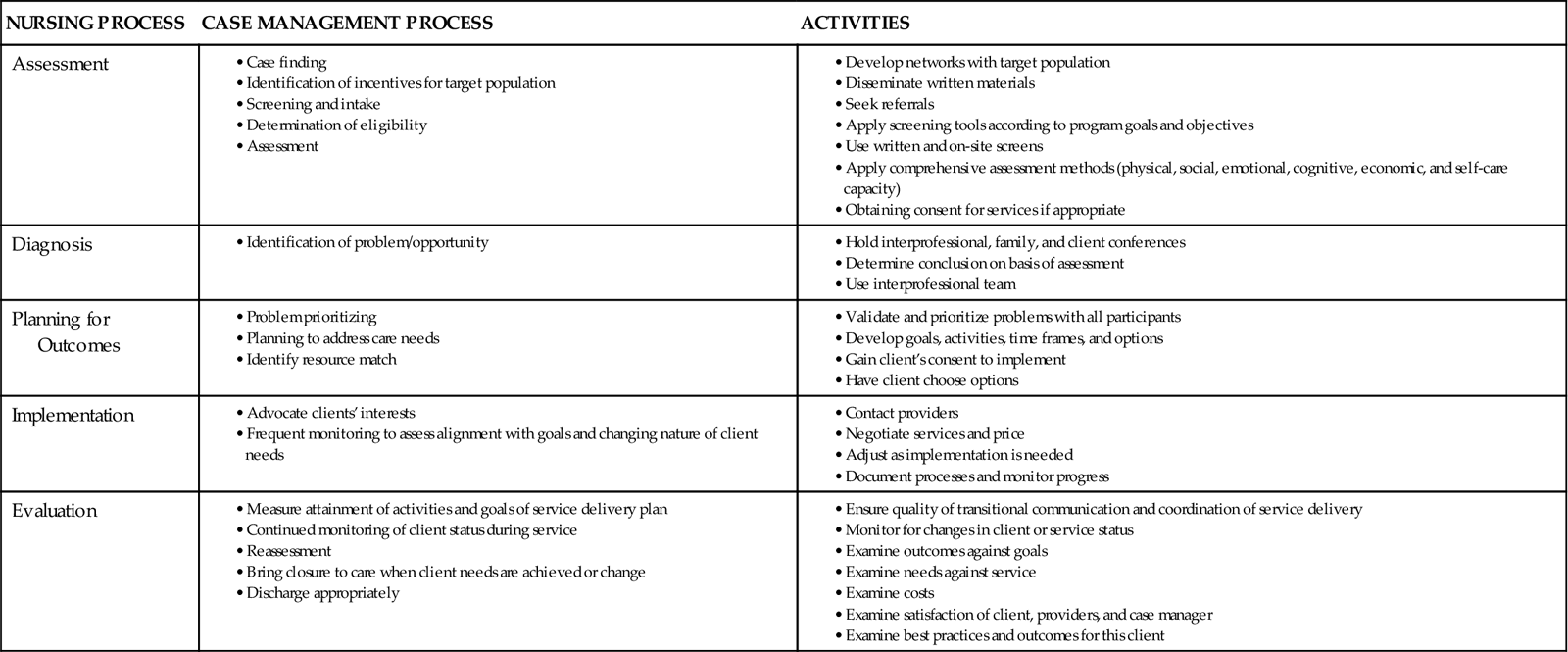

Case Management and the Nursing Process

The nurse views the process of case management through the broader health status of the community. Clients and families receiving service represent the microcosm of health needs within the larger community. Through a nurse’s case management activities, general community deficiencies in quality and quantity of health services are often discovered. For example, the management of a severely disabled child by a nurse case manager may uncover the absence of respite services or parenting support and education resources in a community. While managing the disability and injury claims within a corporation, the nurse may discover that alternative care referrals for home-health visits and physical therapy are generally underused by the acute care providers in the community. Through a nurse’s case management of brain-injured young adults, the absence of community standards and legislative policy for helmet use by bicyclists and motorcyclists may be revealed, stimulating advocacy efforts for changing community policy. Case management activities with individual clients and families will reveal the broader picture of health services and health status of the community. Community assessment, policy development, and assurance activities that frame core functions of public health actions are often the logical next step for a nurse’s practice. When observing lack of care or services at the individual and family intervention levels, the nurse can, through case management, intervene at the community level to make changes. Clearly, the core components of case management and the nursing process are complementary (Table 22-1).

TABLE 22-1

THE NURSING PROCESS AND CASE MANAGEMENT

| NURSING PROCESS | CASE MANAGEMENT PROCESS | ACTIVITIES |

| Assessment | ||

| Diagnosis | ||

| Planning for Outcomes | ||

| Implementation | ||

| Evaluation |

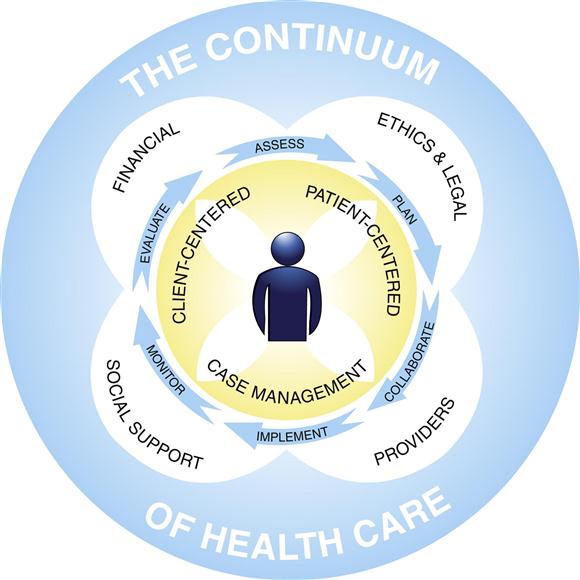

Secord’s (1987) classic illustration of case management remains an appropriate picture of the process that nurses use. The CMSA model (2010) is a contemporary illustration of the case manager’s process in the continuum of care (Figure 22-3).

Characteristics and Roles

Case management can be labor intensive, time consuming, and costly. Because of the rapid growth in the nature of complexity in clients’ problems, the intensity and duration of activities required to support the case management function may soon exceed the demands of direct caregiving. Managers and clinicians in community health are exploring methods to make case management more efficient. In an earlier effort to achieve efficiency (Weil and Karls, 1985), the characteristics desired for case manager effectiveness were described. These characteristics, which incorporated the four CMSA activities (previously noted in the Concepts of Case Management section), are used today (CMSA, 2010):

3. Assertiveness, diplomacy, and negotiation skills with people at all levels

4. The ability to assess situations objectively and to plan appropriate case management services

5. Knowledge of available clinical evidence and resources as well as their strengths and weaknesses

6. The ability to act as advocate for the client and payer in models relying on third-party payment

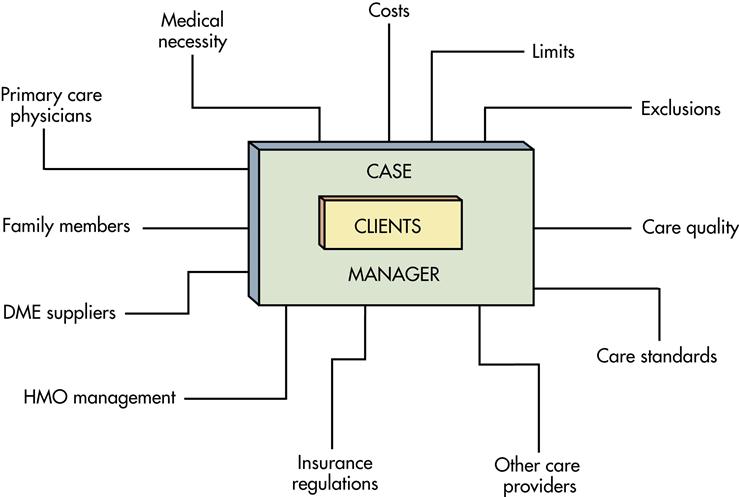

In 1998, Cary described the roles of case managers in the practice setting. These roles are clearly affirmed today in the work of Llewellyn and Moreo (2001) and by the CMSA (2010) (Box 22-1). The roles demanded of the nurse as case manager are greatly influenced by the forces that support or detract from the role. Figure 22-4 presents factors that demand the attention of both the nurse and the client during the case management process.

Knowledge and Skill Requisites

Nurses are not automatically experts in the role of case manager. First, they develop and refine the knowledge and skills that are essential to implementing the role successfully. Knowledge domains useful for nurses in systems desiring to implement quality case management roles are found in Box 22-2 (Cary, 1998; Llewellyn and Moreo, 2001; Stanton and Dunkin, 2009).

When a nurse seeks a case manager position, some of the skills and knowledge will need to be acquired through academic and continuing education programs, literature reviews, and orientation and mentoring experiences. Basic nursing education may need to be updated, while practical experiences in case management may be required. In fact, professional development activities for case managers in public health have been demonstrated to contribute to job satisfaction (Schutt et al, 2010).

Tools of Case Managers

The five “rights” of case management are right care, right time, right provider, right setting, and right price. How does the nurse judge the effectiveness of case management? Three tools are useful for case management practice: case management plans, disease management, and life care planning tools. An underlying principle for use of each of these tools is the need to use robust evidence as the basis for the selection of activities.

Case management plans have evolved through various terms and methods (e.g., critical paths, critical pathways, care maps, multidisciplinary action plans, nursing care plans). Regardless of the title given, standards of client care, standards of nursing practice, and clinical guidelines using evidence-based practices for case management serve as core foundations of case management plans. Likewise, in interprofessional action plans, core professional standards of each discipline guide the development of the standard process.

As early as 1985, the New England Medical Center in Boston instituted a system of critical path development to guide the case management process in the acute care setting. A critical path was described as a case management tool comprised of abbreviated versions of discipline-specific processes; it was used to achieve a measurable outcome for a specific client “case” (Zander, Etheredge, and Bower, 1987). The critical path detailed the essential and sequential activities in care, so that the expected progress of the client was known at a point in time. Outcomes from critical paths included satisfaction, client competency, continuity of care, continuity of information, and costs and quality of care. However, one criticism was that critical paths may not be evidence based (Renholm, Leino-Kilpi, and Suominen, 2002). The prevailing method of establishing critical paths was by internal, “expert knowledge” from a specific institution, the result being that they could not be applied generally or tested under systematic, scientific methods. In the New England model, key incidents included consults, tests, activities, treatments, medication, diet, discharge planning, and teaching. The paths showed the differences between clients’ progress. However, the paths were generally not revised unless a body of evidence was found to adjust the expected actions.

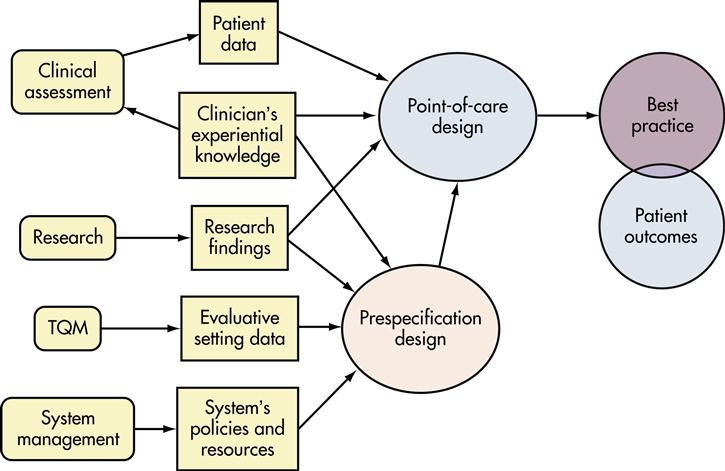

Care maps became the second generation of critical pathways of care. Rather than give definitions, Brown (2001) discussed the “various types of evidence that must be accessed, interpreted, and integrated into care design.” Brown (2001, p 3) proposed the Best Practice Health Care Map (BPHM) as a model for providing quality clinical care within an interprofessional practice. This model discussed all the components of knowledge development and care planning activities that must occur to have positive client outcomes. The author noted that care designed in advance takes the form of “clinical guidelines, care maps, decision algorithms, and clinical protocols for specified populations of clients” (Brown, 2001, p 3). The “Pre-specification Design” of the BPHM entailed these preplanning courses of care. Brown (2001) stressed the importance of incorporating research findings and clinical experience when developing prespecified plans. Furthermore, the author emphasized that at the point of care, these prespecified plans must be adapted to the individual client or population.

The Brown BPHM was: (1) client centered, (2) scientifically based, (3) population-outcomes based, (4) refined through quality assessment and compared with other maps, (5) individualized to each client, and (6) compatible with the larger system of health care in the United States such activities are more likely referred to as case management plans, care maps, and integrated clinical pathways (Figure 22-5).

Adaptation of the case management care plan to each client’s characteristics is a crucial skill for standardizing the process and outcome of care. It links multiple provider interventions to client responses and offers reasonable predictions to clients about health outcomes. Institutions report that sharing case management plans with clients empowers the clients to assume responsibility for monitoring and adhering to the plan of care. Self-responsibility by clients incorporates autonomy and self-determination as the core of case management. For the nurse employed to function as a case manager, ample opportunity exists to develop, test, and revise critical path/map prototypes for a target population experiencing acute health problems.

Disease management is an organized program of coordinated health care interventions and communications for populations with conditions in which client self-care efforts are critical (CMSA, 2010). This approach focuses on the natural progression of a disease. Disease management programs may contain many of the following components (DMAA, 2008, 2010):

• Financial and risk sharing arrangements between payers and providers

• Protocols for clinical and administrative processes as well as cost allocations

• Services to educate clients and promote self-management skills

• Enhanced quality through evidence-based decision support and other registry technologies

• Support for provider/client relationships and plans of care