There are readily available tools in cardiothoracic units that can be used to automatically calculate this value, but the patient’s height and weight need to be recorded to enable this. The normal values are 1.9 m2 for men and 1.6 m2 for women. These values are used for drug dose calculations and to calculate the amount of intravenous fluids required by the patient. Renal function and cardiac output measurements can also be calculated with this information.

- Echocardiographic assessment prior to valve surgery is crucial for clinical decision making, timing of surgery, planning the appropriate surgical therapy and predicting the patient’s outcome (Germing and Mügge, 2009).

- Anti-platelet drugs should be stopped 5–9 days prior to surgery to reduce the risk of bleeding complications, unless specifically contraindicated (Cahill et al., 2005).

- Patients should be encouraged to discuss any particular worries they have in an effort to allay their fears and a visit to the intensive care unit should be undertaken so they view the environment and machinery before they are admitted.

The Operation

Traditionally, cardiac surgery is performed using a median sternotomy of 6–8 inches in length, allowing the surgeon to access the heart and put the patient on to a cardiopulmonary bypass machine. This machine bypasses the lungs and heart to enable the heart to be operated on while it is still and bloodless, and the lungs to be deflated to maximise visualisation of the operative site; it allows temporary disruption to the circulatory system without causing global ischaemia (Margerson and Riley, 2003). An alternative to traditional CABG is off-pump or beating-heart surgery, where surgeons do not use the heart-lung machine. The procedure is also called OPCAB (off-pump coronary artery bypass). The surgeons sew the bypasses onto the heart while it continues to beat. High-risk patients with additional diseases such as lung disease, kidney failure or peripheral vascular disease may benefit from this technique.

- Cardioplegia is given to arrest the heart while in theatre; cardio means the heart, and plegia means paralysis. To achieve this, deoxygenated blood entering the heart through the superior and inferior vena cavae are diverted using venous canulae to the cardiopulmonary bypass machine. This pump takes over the function of the lung by oxygenating the blood and removing carbon dioxide using an oxygenator in the circuit. After oxygenation, filtration and removal of carbon dioxide, the blood is pumped back into the body, usually through the aorta, although the femoral artery and the right axillary artery can be used.

- The heart is then isolated from the rest of the body by a cross-clamp on the aorta and cold cardioplegia is introduced into the heart through the aortic root. The blood supply to the heart arises from the aortic root through the coronary arteries. The cold fluid (usually at 4°C) ensures that the heart cools down to an approximate temperature of around 15–20°C. This is further augmented by the cardioplegia component, which is high in potassium and magnesium. The potassium helps by arresting the heart in diastole, thus ensuring that the heart does not use up the valuable energy stores (adenosine triphosphate). Blood can be added to this solution, particularly for long procedures requiring more than half an hour of cross-clamp time. Blood acts a buffer and also supplies nutrients to the heart during ischaemia.

- During bypass conduits are used to bypass the diseased arteries enabling a superior flow to the myocardium. Conduits used are the long saphenous veins and internal mammary arteries; sometimes radial arteries are used but this is rarer. The gastro-epiploic artery has been used, but because this artery is in the abdomen it lengthens the operative time and is currently used less often than other conduits.

- Hypothermia is defined as a core temperature below 36.8°C. While hypothermia can be a consequence of many types of surgery because of the inhibition of central thermoregulation and exposure to cold operating rooms, in cardiac surgery hypothermia is induced while the patient is on the bypass machine. The rationale for the use of hypothermia is based on its capacity to reversibly reduce metabolic activity in all cells and subcellular organelles, such as the mitochondria and the nucleus of the cell, further limiting the rate of consumption of intracellular high-energy phosphate stores and limiting ischaemic injury. This results in slower metabolism and reduced cardiac demands. As well as the positive effects, hypothermia also has some negative effects, two of the most important being the delirious influence on platelet function and the increase in citrate toxicity with a reduction in serum ionised calcium. These effects can result in coagulopathies, making the patient more susceptible to bleeding in the postoperative period, and dysrhythmias with depression of myocardial contractility (Lewis et al., 2002; Ning et al., 1998; Tonz et al., 1995).

- Advances in technology have now made it possible to perform beating heart surgery where the patient does not have to be put on a bypass machine. There are obvious benefits to this as the risks of morbidity and mortality are greatly reduced. Minimally invasive direct CABG (MIDCABG) is useful when there is one vessel disease, for example a left anterior descending artery blockage where the left internal mammary artery can be used. There have also been advances in robotically assisted surgery for MIDCABG.

- A transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has recently been introduced for use in patients who are considered by the multidisciplinary team to be too high a risk for valve surgery. This is performed on a beating heart and avoids the need for sternotomy. It can be performed via transfemoral, subclavian or transapical approaches. Recommendations by the British Cardiovascular Society and the Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery suggest that at least 50 cases per year are performed for the procedure to be optimal (www.scts.org/documents/PDF/BCISTAVIDec2008.pdf).

Postoperative Care

The main aim in the first 24 hours following cardiac surgery is haemodynamic stabilisation and minimising myocardial ischaemia (Myles et al., 1997). Careful, continuous monitoring of the patient should be undertaken with one registered nurse caring for the patient. The patient’s care will be discussed using a systems approach to ensure all elements are covered.

On their return to the ward, the nurse should receive a thorough report about the patient’s progress in theatre from the anaesthetist and be informed of any problems that were encountered during the operation. When the patient is stabilised, routine bloods should be checked, including an activated partial thrompoplastin time (APPT) and an international normalised ratio (INR). Routine taking of chest X-rays and ECGs can no longer be justified postoperatively when there is no clinical sign of disease, but a chest X-ray following drain removal to identity pneumothorax and one ECG postoperatively should be recorded.

Respiratory

The patient should be attached to a ventilator. The mode of ventilation (pressure or volume) is less important than the achievement of optimum ventilation with appropriate tidal volumes.

- In patients with no pre-existing lung disease, volumes of 10–12 ml/kg should be achieved with a rate of 12 breaths per minute. In patients with pre-existing lung disease the tidal volume achieved should be smaller, about 8–10 ml/kg.

- Airway pressures should not exceed 45 cm H2O in order to prevent barotrauma.

- When using volume controlled ventilation positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) should be added at 5 cm H2O to oppose the passive emptying of the lungs. This works by increasing the alveolar pressure and volume, which facilitates splintage of the airways. PEEP can also be used up to 10 cm H2O to increase the airway pressure when patients are bleeding.

- After initialising ventilation, auscultation of the chest should be performed to check for bilateral air entry and ensure there is no pneumothorax or that the endotracheal tube has not slipped into the right main bronchus during the transfer from theatre.

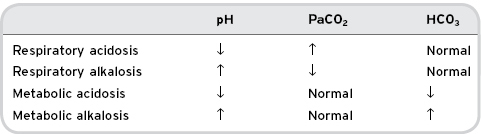

- Arterial blood gases (ABG) should be monitored regularly to ensure ventilation is adequate and to highlight when changes are needed to optimise ventilation. Table 9.1 provides a quick reference guide, more information can be found in Coggon (2008).

Table 9.1 Changes found in arterial blood gases in patients with respiratory and metabolic conditions

After a period of stability the decision to wean and wake the patient should be made. The patient should be haemodynamically stable, bleeding should be minimal (less than 50 ml/hour for two consecutive hours), temperature should be reaching normal and oxygenation should be optimum (PO2 greater than 10 kilopascals, kPa).

- After cardiac surgery it is common for patients to develop microatelectasis due to the fact that the lungs are collapsed during surgery and the anaesthetic gases used decrease the mucocilliary clearance (Margerson and Riley, 2003). This, plus the haemodilution from cardiopulmonary bypass, leads to extravascular fluid and the need for patients to have active physiotherapy postoperatively.

- Early ambulation and deep breathing techniques help prevent chest infections. Deep breathing techniques and “huffing” should be taught so the patient can understand and practise these when the physiotherapist is not present. If sputum is purulent, a specimen should be sent for culture and sensitivity.

- Antibiotics should not be given routinely unless the patient presents with other empirical data, for example a raised white cell count and pyrexia.

- Early ambulation also helps to prevent deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. A low molecular weight heparin should be prescribed daily as prophylaxis and thrombo-embolic stockings should be prescribed, according to the guidleines published by the Department of Health in 2010 (www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publichealth/Healthprotection/Bloodsafety/Venous ThromboembolismVTE/DH_113359).

- Vital signs should be recorded hourly in the immediate postoperative period and reduced to two-hourly then four-hourly as the patient progresses. Four-hourly vital signs should be continued while the patient is hospitalised, as often patients are discharged home on the fourth or fifth postoperative day.

- The majority of patients are only ventilated for a short period of time and can therefore resume their own oral toileting within a few hours, but in patients who are ventilated for more than a few hours oral care is important to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia (Lorente et al., 2007).

Cardiovascular

Continuous ECG monitoring is carried out in theatre and this should be continued on return to the intensive care unit to observe for arrhythmias. Continuous monitoring of arterial and central venous pressures should also be recommenced. The arterial line in the patient’s arm should be visible and not hidden by bed sheets so the nurse can observe for signs of bleeding.

There are a number of cardiac complications that can occur after surgery. They may be considered as either pre-cardiac, cardiac or post-cardiac and close observation is required in the 24 hours following surgery.

Pre-Cardiac Complications

- Hypovolaemia may be classed as a pre-cardiac issue. This may present as hypotension, and a central venous pressure (CVP) reading should then be taken. One lumen of the CVP should be used for measurement only, no other fluid should go through this line as this may give a falsely high reading. Other fluids going through the line may give a falsely high CVP reading. If it is not possible to do this, all other infusions going through the measurement port should be discontinued before a reading is taken. It is advisable not to put other infusions on the line where the CVP is being measured as bolus doses can be given when flushing the line, which can lead to hypotensive or hypertensive crises. If the CVP is low and the haemoglobin (Hb) is greater than 7 g/dl, crystalloid fluids should be given until the CVP is within normal parameters. If the Hb is less than 6 g/dl and the patient is actively bleeding, blood should be given.

Cardiac Complications

Cardiac complications include tamponade, arrhythmias and coronary spasm.

- If the CVP is raised, the urine output is low and the patient is hypotensive, cardiac tamponade should be considered. An urgent chest X-ray may reveal a widened mediastinum, which may be an indicator of tamponade. The treatment for tamponade is to return to theatre for reopening and release of the tamponade. If the patient deteriorates rapidly, emergency reopening in the intensive care unit is indicated.

- Fatal arrhythmias such as asystole and ventricular fibrillation can occur due to the increased secretion of catecholamines resulting from the stress response. Shifts of potassium into the cell may lead to hypokalaemia. For this reason potassium is checked hourly and replacements are given to maintain serum potassium of 4–4.5 mmol/l.

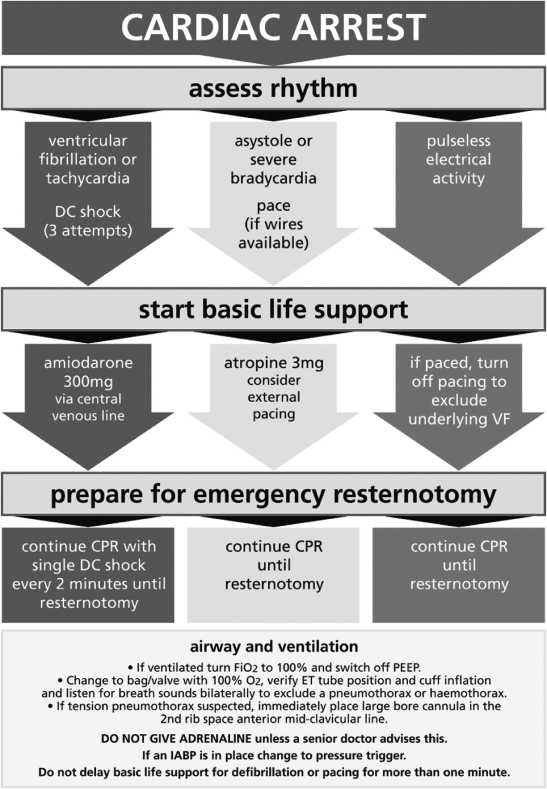

- Coronary artery spasm can occur and presents as ST segment elevation and ventricular arrhythmias (Margerson and Riley, 2003). The treatment for this is a nitroglycerine infusion titrated according to parameters set by the anaesthetist. The guidelines for cardiac arrest post cardiac surgery differ from the Resuscitation Council guidelines and have recently been accepted by the European Association for Cardiac and Thoracic Surgery (Dunning et al., 2009). These recommendations state that in ventricular fibrillation post cardiac surgery, three consecutive shocks should be given before giving cardiac massage or resuscitation drugs. If the shocks are unsuccessful the recommendation is that the patient’s chest should be opened as soon as possible in the intensive care unit (Dunning et al., 2009) (see Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1 Guidelines for resuscitation in cardiac arrest after cardiac surgery.

From Dunning et al. (2009). Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree