Chapter 5

Cardiac and Vascular Care Plans

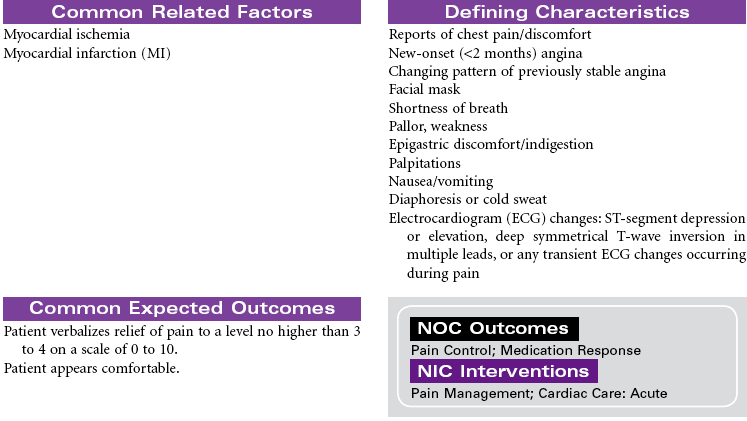

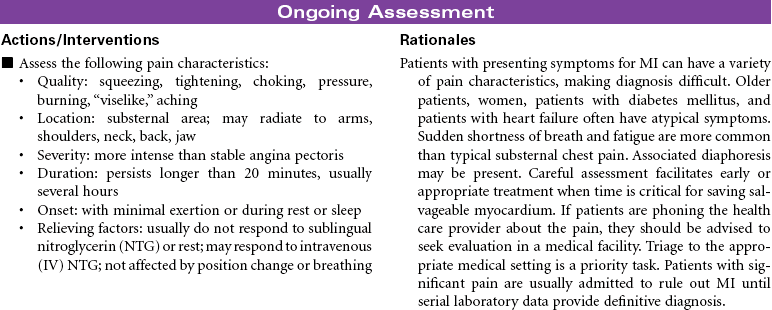

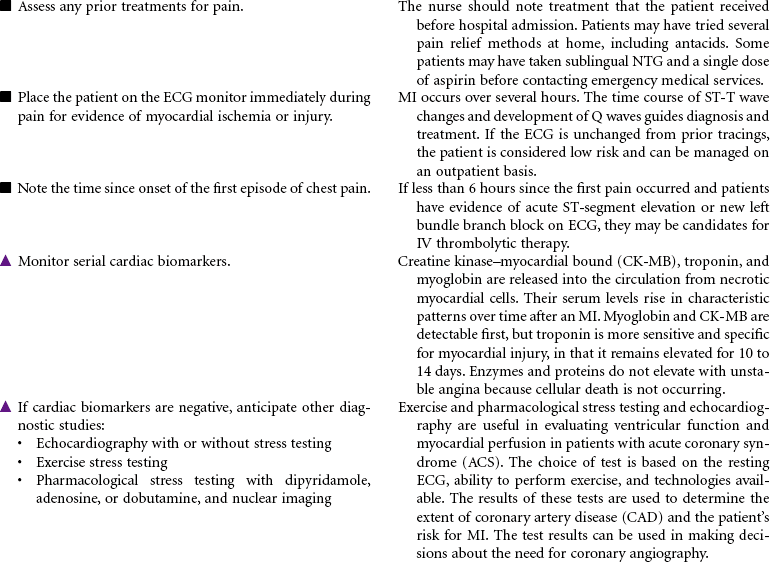

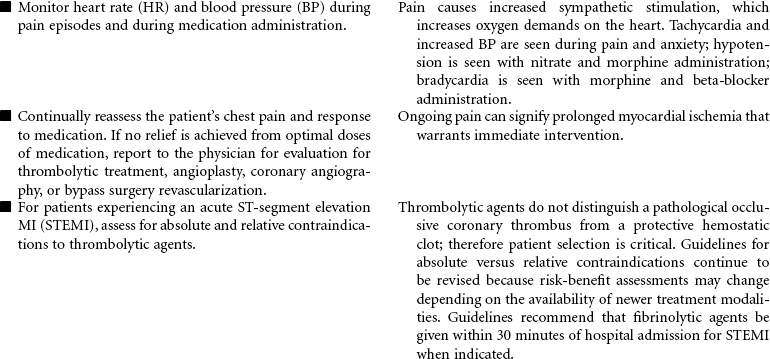

Acute Coronary Syndromes/Myocardial Infarction

![]() For additional care plans and an Online Care Plan Constructor, go to http://evolve.elsevier.com/Gulanick/.

For additional care plans and an Online Care Plan Constructor, go to http://evolve.elsevier.com/Gulanick/.

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

= Independent

= Independent  = Collaborative

= Collaborative