Electronic health record systems

Gretchen F. Murphy and Susan Helbig

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

• Describe electronic health records in various care settings.

• Explain how improving the quality of patient care links to electronic health records.

• Build a case for electronic health records as central components in integrated and networked systems.

• Discuss how personal health records can be linked to Electronic Health Record Systems.

• Review the progress in electronic health record development.

• Illustrate patient safety improvements.

• Explain how progress in EHR implementation is measured through levels and stages.

• Describe key functions, requirements and expectations for electronic health records.

• Relate accreditation and regulatory requirements to EHR systems.

• Explain how the certification process (CCHIT) affects EHR products and the health care industry.

• Contrast clinician and other user needs in an electronic health record environment.

• Describe technical building blocks and illustrate information system components.

• Contrast roles and functions of clinical data repositories and data warehouses.

• Discuss the role of systems migration in meeting EHR goals.

• Evaluate health information management business processes.

• Recognize change in the electronic health record environment.

• Identify resources and strategies needed by health information management professionals to lead and participate in electronic health record projects.

• Describe the obstacles encountered in progressing toward electronic health records.

• Define and characterize interoperability for health information technology and EHRs.

• Illustrate how informatics standards lead to assessment of “meaningful use” of EHR systems.

Key words

Authentication

Biomedical device

Classification system

Clinical data repository

Clinical guidelines

Computer-based patient record

Confidentiality

Data

Data dictionary

Data interface standards

Data security

Data warehouses

Document

Electronic health record

Health care information

Health informatics

Information

Infrastructure

Internet

Knowledge

Multimedia

Natural language processing

Nonrepudiation

Patient record

Patient record system

Personal health record

Primary patient record

Privacy

Registration-admission, discharge, and transfer

Script-based systems

Template

Text processing

Vocabularies

Abbreviations

ADT—Admission, Discharge, Transfer

AHIMA—American Health Information Association

AMIA—American Medical Informatics Association

ANSI—American National Standards Institute

ASTM—American Society for Testing and Materials

CCHIT—Commission on Certification of Health Information Technology

CDS—Clinical Decision Support

CPOE—Computerized Physician Order Entry

CPR—Computer-Based Patient Record

CPT—Current Procedural Terminology

DICOM—Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine

DSTU—Draft Standard for Trial Use

ECG—Electrocardiogram

EHR—Electronic Health Record

ESC—Evidence of Standards Compliance

HIE—Health Information Exchange

HIM—Health Information Management

HIMSS—Health Information Management Systems Society

HIPAA—Healthcare Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

HISB—Health Care Informatics Standards Board

HL7—Health Level 7

HMO—Health Maintenance Organization

HTML—Hypertext Markup Language

ICD—International Classification of Diseases

IEC—International Electrotechnical Commission

IEEE—Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers

IOM—Institute of Medicine

ISO—International Standards Organization

IT—Information Technology

JCAHO—Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (now The Joint Commission)

LHR—Legal Health Record

MPI—Master Patient Index

NCPDP—National Council on Prescription Drug Programs

ONCHIT—Office of the National Coordinator of Health Information Technology

PACS—Picture Archiving and Communication System

PHR—Personal Health Record

RADT—Registration-Admission,Discharge,Transfer

REG-ADT—Registration-Admission, Discharge, Transfer

RHIO—Regional Health Information Organization

RIO—Release of Information

SGML—Standard Generalized Markup Language

SNOMED—Systematized Nomenclature of Human and Veterinary Medicine

SSN—Social Security Number

UHDDS—Uniform Hospital Discharge Data Set

UACDS—Uniform Ambulatory Care Data Set

XML—Extensible Markup Language

Student Study Guide activities for this chapter are available on the Evolve Learning Resources site for this textbook. Please visit http://evolve.elsevier.com/Abdelhak.

When you see the Evolve logo  , go to the Evolve site and complete the corresponding activity, referenced by the page number in the text where the logo appears.

, go to the Evolve site and complete the corresponding activity, referenced by the page number in the text where the logo appears.

Electronic health records: the case for quality and change

The desire to leverage technology to improve patient safety, reduce costs, and improve care—long endorsed by health care providers and more recently championed by government and standards organizations—is creating enormous momentum for the electronic health record (EHR).1 The pace of commitment to adoption of EHRs continues to accelerate, and more institutions are achieving industry benchmarks in EHR systems. Along with the steady growth, analysis and research on EHR benefits and challenges are emerging, enough both to entice and give pause in considering the work ahead. We begin this chapter with a snapshot of the complexity of EHR systems and their development, followed by a stepwise look at EHR definitions, content and functions, standards, and infrastructure. Discussion of the legal health record (LHR), the personal health record (PHR), and the EHR as they develop in a health care setting contributes ideas on how EHR systems could expand to better serve various customers. This chapter features the Computerized Patient Record System at the Veterans Administration of Puget Sound in Seattle, an award-winning advanced EHR system, supported by a nearly virtual health information department. The chapter concludes with a look at progress, including benefits and challenges, and presents strategies that health informatics and health information managers need to meet current and future demands in the rapidly changing environment.

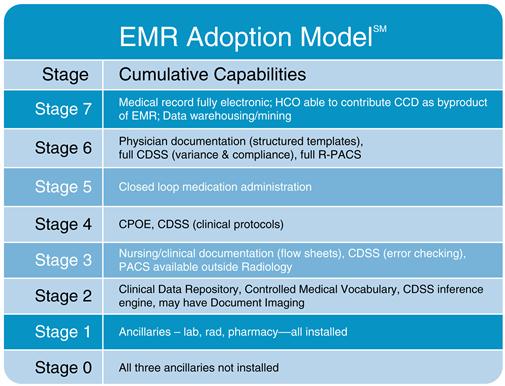

Analysts interested in understanding the pace of EHR advancement have projected development and adoption patterns for many years. The Health Information Management Systems Society (HIMSS) Analytics model of Electronic Health Record Systems adoption trends in hospitals illustrates how functions and capabilities build on each layer of development, leading to an advanced system. In Figure 5-1, notice how the applications evolve and electronic information increases for the users as organizations achieve more comprehensive EHR capabilities.2 Hospitals are not alone in their progress. Ambulatory care EHR systems are also advancing steadily. In a 2008 national survey of physicians, 41.5% reported using all or partial EHR systems. By 2009, the number increased to 43.9%, and 6.3% reported having an extensive, fully functional system. Table 5-1 contrasts basic with fully functional EHR systems in ambulatory care settings.3 Many features are consistent with hospital EHRs. Today, most ambulatory care EHR applications are certified by the Commission on Certification of Health Information Technology (CCHIT). In fact, CCHIT criteria comprise the fully functional ambulatory EHR featured in this table. The CCHIT organization exerts is a growing influence on institutions and vendors as the industry grows. It certifies EHR products against specific criteria for functionality and is featured in the later discussion on EHR standards. Common components of hospitals and ambulatory sites are evident in the figure and table presented. The EHR picture is coming together.

Table 5-1

AMBULATORY ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORD SYSTEMS

| Functionality | Basic Systems | Fully Functional Systems |

| Patient demographic information | X | X |

| Patient problem lists | X | X |

| Clinical notes | X | X |

| Orders for prescriptions | X | X |

| Viewing laboratory results | X | X |

| Viewing imaging results | X | X |

| Medical history and follow-up | X | |

| Orders for tests, prescriptions and test orders sent electronically | X | |

| Warnings of drug interactions or contraindications | X | |

| Highlighting out of range test levels | X | |

| Reminders for guideline-based interventions | X |

Source: Hsiao C-J, Beatty PC, Hing ES, et al: Electronic medical record/electronic health record use by office based physicians: United States, 2008 and Preliminary, 2009 (NCHS E-Stat), Atlanta, GA, December 2009, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/emr_ehr/emr_ehr.htm.

With the passage of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) legislation in 2009, with its specific attention to advancing EHRs, federal dollars have been dedicated to expanding their use in physician offices and more. Furthermore, monies were set aside to help build technical infrastructure to enable providers and patients to exchange information across sites.4 Pilot demonstrations that address interoperability across community providers’ settings are in place in several states and municipalities. Washington, Massachusetts, Vermont, and New York City have all dedicated funding for advancing electronic PHR banks, EHRs, or networks to aid in interoperability in their region.5–7

Yet significant challenges continue, and we are a long way from EHR products that are easy to install, fully functional, and interoperable—products that can truly take the place of the paper record systems that litter health care institutions around the country. Health information management (HIM) now and in the future requires knowledge of EHR systems, organizational leadership, understanding of data and interoperability capacity, and changes in management skills to advance the implementation of quality EHR systems.

The previous chapter featured patient records in primarily paper and hybrid record systems; this chapter focuses on the evolving status of EHR systems and their impact on the care delivery process and on health informatics and health information management. As the technology, standards, and meaningful use develops and deepens, bridging data from enterprise to provider practice to individual patient PHRs will be the challenge for information users. Identifying and harmonizing data definitions among disparate systems, mapping the flow of information, and expediting its seamless movement across settings will be the foundation for a national health information highway. What is clear today is the steady development and deployment of technology in health care organizations, with the EHR central to that effort.

Even before EHR systems are acquired, incremental changes occur as patient record components are processed, maintained, and provided electronically. Institutions offer their clinicians online access to transcribed documents. Providers admit their patients to hospitals using online links from their offices. Provider offices scan and transmit patient record content to support referrals. In addition, disparate systems and products are linked to form parts of an EHR system. One hospital may have a “registration-admission, discharge, transfer” (REG-ADT) administrative system and a radiology imaging system. Online diagnostic applications and lab tests, EKG, and radiology results may be posted for online viewing in another location. Many organizations are in transition with one or more pieces of an EHR in place. As the industry experiences positive feedback from EHR systems with improved access to patient information, streamlined services and links among provider offices, hospitals, and specialty services, more hospitals and other health care organizations become willing to invest in EHRs to acquire capabilities far beyond those found in paper record systems.

Health informatics and HIM professionals are being prepared to manage systems in transition and understand how new technology fundamentally changes what happens on a daily basis and in the longer term. They meet professional responsibilities as they change in the EHR environment and are now managing systems’ initiatives and relevant life-cycle activities. They broker health record data and help patients participate in their own health management processes through enterprise patient portals to their provider organization’s health records and through PHRs available in a variety of formats.

In guiding the discussion through this chapter, overarching questions provide a framework to understand the momentum toward EHRs, describing them, explaining their components, and examining how they operate within the health care system. The challenges faced for those managing the culture, cost, and changes to EHRs are considered. We need to understand EHR systems from the what, why, how, and where perspective. Here are questions to guide our discussion through this chapter:

• What are EHR systems, and how do they work?

• How does the record itself develop in the electronic environment?

• How do HIM business processes change in the EHR environment?

• How are organizational policies and procedures being updated to guide EHR users and systems?

• How should HIM professionals lead and participate in EHR transition work?

The patient record

As described in the previous chapter, the patient record is the principal repository for information concerning a patient’s health care, uniquely representing patients and serving as a dynamic resource for the health care industry. Over time, it paints a longitudinal picture of health problems and services for individuals and, collectively, for the industry itself.

With ongoing advances in technology and compelling evidence of practical benefits in health IT, recent years have seen major changes. Although still rooted in paper-based models, the medical record is rapidly changing. In many settings, it has moved to a hybrid paper and electronic format or to a fully electronic format. Today, patient record systems may store data electronically through online systems, maintain clinical data repositories, use links to diagnostic applications for ongoing information, and combine these elements with scanned copies of paper images so that users can access the entire record through secure devices.

The challenge to the industry is twofold. First, the information contained in patient records continues to expand in content and form to include text; waveforms; imaging studies such as chest films acquired, stored, and displayed in digital form; monitoring data such as vascular pressures, ventilator, and heart-monitoring data; videos; and more.8 Second, the technology that enables making that content available for health care team members across care settings through interoperability resources is becoming a realistic option in more environments. Chapter 4 outlined a substantial list of uses and users of the patient record. As the source and record of individual care that provides the aggregate data necessary to assess care effectiveness, the EHR must meet past, current, and future demands. As the migration to electronic records proceeds, users need to be able to rely on a transition record system to meet their needs while working toward a fully electronic system that can provide additional data and capabilities. Those who manage EHRs need to build skills that support uses of the record for traditional purposes and for more sophisticated quality and research monitoring of health care processes and events. Eventually, the full implementation of EHRs and health information exchanges (HIEs) should assist in transforming individual patient data and health information into knowledge and wisdom resources that help manage the health of our many communities across the United States.

Industry forces that advance electronic health record adoption

Patient safety concerns, a national focus on health IT, health services quality, paper record shortcomings, and cost containment demands have strengthened the historical drivers to EHR adoption. National debates and reports are shining a spotlight on health care facts that call for correction and for using technology more effectively. Among six trends noted by the Gartner Research Group on Information Technology, “A 50% growth in healthcare software investment could enable clinicians to cut the level of preventable deaths by half in 2013.”9 This prediction reflects the gathering energy for applying technology to the health care process. In 2008, the New England Journal of Medicine reported that physicians identified positive effects of EHR systems in several dimensions of quality of care and high levels of satisfaction.10

Patient safety concerns

Since 2000, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) issued a series of critical reports on the nation’s health care on the basis of a concerted, continuing effort focused on a 1996 initiative to assess and improve the nation’s quality of care. In a key report, “To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System,” the authors cite that between 44,000 and 98,000 U.S. deaths per year were caused by medical errors.11 In the follow-up report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century,” the authors call for better systems and better data.12 Following these landmark reports, endorsements for industry investment in EHRs and better information sharing grew substantially. Industry leaders, professional organizations, and payers added their perspectives. Notable work by the Markel Foundation’s public-private collaborative, Connecting for Health, and the Leapfrog Group invested in partnerships with government, industry, health care, and consumers to expand the discussion and strengthen the drive to focus on patient safety by improving the health information needs for the country.13,14

Substantial progress in hospital EHR systems in the Veterans Administration offers significant evidence that care can be improved and become more efficient when these systems are used.15 With data availability improved through their EHR and specialized registries, the Kaiser system demonstrated patient safety improvements by combining the technology with new care team measures to reduce cardiac deaths by 73%.16 The Geisinger Clinic, an integrated delivery system serving a population of 2.5 million members, demonstrated returns on innovation over ambulatory services and a fully implemented hospital EHR by emphasizing collaboration of clinical, operational, payer, and selected patients to identify which care model will offer the most value. The team links redesign of the care process, improving the clinical workflow and key process steps within the EHR with the decision support system and patient engagement and calls for metrics to monitor progress.17

National focus on improving health information and technology

In April 2004, President Bush called for “the majority of Americans to have interoperable electronic health records within 10 years,” named a national coordinator for health information technology, and established the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONCHIT).18 The national coordinator, Dr. David Brailer, delivered a critical new strategic framework and set four goals that are still targeted today: