Privacy and health law

Jill Callahan Dennis

Objectives

• Distinguish between confidential and nonconfidential information within a health information system.

• Have a basic understanding of the federal and state court systems.

• Describe the four components of negligence.

Key words

Advance directive

Alternative dispute resolution

Antitrust

Arbitration

Assault

Authentication

Authorization

Bailiff

Battery

Best evidence rule

Breach of contract

Burden of proof

Business associate agreement

Case law

Charitable immunity

Clerk of the court

Common law

Complaint

Confidential communications

Consent

Contemporaneous documentation

Contract

Corporate negligence

Court order

Court reporter

Covered entity

Credentialing

Defamation

Defendant

Deidentified

Deposition

Designated record set

Discovery

Due process

Durable power of attorney for health care

Emancipated minor

Evidence

False imprisonment

Fraud

Health care operations

Hearsay rule

Incident report

Informed consent

Institutional review board

Intentional tort

Interrogatory

Invasion of privacy

Jurisdiction

Legal medical record

Libel

Living will

Malpractice

Minimum necessary

Motion to quash

Negligence

Occurrence report

Plaintiff

Pleading

Power of attorney

Precedent

Preempt, preemption

Preponderance of evidence

Privacy

Privileged communication

Protected health information

Proximate cause

Qui tam

“Reasonable man” standard

Regulation

Res ipsa loquitur

Respondeat superior

Restraint of trade

Right of privacy

Satisfactory assurance

Security of health information

Slander

Standard of care

Stare decisis

Statute

Statute of limitations

Subpoena

Subpoena duces tecum

Tort

Whistleblower

Workforce

Abbreviations

AHA—American Hospital Association

AHIMA—American Health Information Management Association

ARRA—The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009

CFR—Code of Federal Regulations

CMS—Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services

DHHS—Department of Health and Human Services

DRS—Designated Record Set

EMTALA—Emergency Treatment and Active Labor Act

FOIA—Freedom of Information Act

HIM—Health Information Management

HIPAA—Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

HIV—Human Immunodeficiency Virus

IIHI—Individually Identifiable Health Information

IRB—institutional review board

JCAHO—Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (now The Joint Commission)

MIB—Medical Information Bureau

NPDB—National Practitioner Data Bank

OIG—Office of the Inspector General

PHI—Protected Health Information

Student Study Guide activities for this chapter are available on the Evolve Learning Resources site for this textbook. Please visit http://evolve.elsevier.com/Abdelhak.

When you see the Evolve logo  , go to the Evolve site and complete the corresponding activity, referenced by the page number in the text where the logo appears.

, go to the Evolve site and complete the corresponding activity, referenced by the page number in the text where the logo appears.

Why are legal issues important to health information management professionals?

At this moment, personal information about the health care or health status of millions of people is being collected, recorded, reviewed, analyzed, transmitted, used, and even misused. For every person who goes to a physician, clinic, hospital, or other treatment provider, somewhere there is a data set related to that visit or treatment. There is a record of all births, every operation, every treatment episode, every test result.

Health information management (HIM) professionals design and manage the information systems that hold these vital records. Earlier chapters have discussed some of the reasons these records are kept. Scores of people and organizations want and need health information. As a result, health care providers are required by law to maintain these records. HIM professionals must ensure that the information systems they manage, run, or design meet these obligations. This chapter discusses some of those obligations.

Some requests for health information are legitimate. Others are not. How do HIM professionals decide which requests are valid and which are not? For the requests that are granted, how do HIM professionals decide what can be disclosed and what cannot? HIM professionals are called on to make these decisions every day. In a health care facility, the HIM professional is the resident expert on these questions. Legal counsel is not always readily available. To make wise decisions—decisions that appropriately protect the confidentiality of health information—HIM professionals must be aware of the rules, regulations, and laws that govern access to health information. A large part of this chapter is devoted to access issues. The rules that govern access to and disclosure of health information are fluid and often thorny. For many HIM professionals, these issues are among the most interesting they encounter in their career.

Why are legal issues so important to HIM professionals? It is because HIM professionals are relied on to understand these issues by the following people and entities:

• Patients or clients whose health information they manage

• Health care organizations in which they are employed

HIM professionals must take this trust seriously. By gaining a good understanding of legal issues, HIM students and professionals can be worthy of that trust.

Fundamentals of the legal system

In civilized societies, laws guide actions. These laws set forth principles and processes for our actions and for handling disputes over those actions. Laws govern both our private relationships (the relationships between private parties) and our public relationships (the relationships between private parties and the government).

Private law consists of two types of actions: tort actions and contract actions. In a tort action, one party alleges that another party’s wrongful conduct has caused him or her harm. The party bringing the action to court seeks compensation for that harm. In a contract action, one party alleges that a contract exists between himself or herself and another party and that the other party has breached the contract by failing to fulfill an obligation that is part of that contract. The party bringing the contract action seeks either compensation for the breach or a court order to force the breaching party to fulfill that obligation.

Public law is composed of rules, regulations, and criminal law. Congress has charged various governmental agencies with the responsibility of overseeing various aspects of many of our nation’s most important industries, including health care. These agencies, acting under the authority of state and federal statutes, issue rules and regulations that touch every department of every health care organization. They cover diverse subjects, such as laboratory safety, incineration of medical waste, employment policies, confidentiality of health records and peer review records, and mandatory reporting of medical device failures or problems. Failure to follow these rules can involve monetary penalties as well as criminal penalties. In addition to these rules and regulations, public laws include a body of criminal law—laws that bar conduct considered harmful to society—and set forth a system for punishing “bad acts.”

Sources of law

Laws that affect the health care system come from four main areas:

• Federal and state constitutions—the supreme law of the nation and state, respectively

• Federal and state statutes—laws enacted by Congress and state legislatures, respectively

Constitutional law

The U.S. Constitution grants certain powers to the three branches of the federal government: executive, legislative, and judicial. It also grants certain powers to the individual states. Powers granted by the Constitution may be either express or implied. Express powers are those specifically stated in the Constitution, such as the power to tax and the power to declare war. Implied powers are not specifically listed in the Constitution. They are the actions considered “necessary and proper” to permit the express powers to be accomplished.

The Constitution also limits what federal and state governments can do. For example, the first 10 amendments to the Constitution—the Bill of Rights—protect the rights of citizens to, among other things, free speech, freedom of religion, and due process before deprivation of life, liberty, or property. In a public health care facility (which is considered a governmental unit, as opposed to a private nongovernmental facility), a physician’s appointment to the medical staff is considered a property right. Therefore, before that appointment could be terminated or rejected, the hospital would be obliged to provide due process to that physician, such as by a full hearing.

Another constitutional right important to the health care industry is the right of privacy, although that right is not an express one. What is the right to privacy? Generally, it is considered to be a constitutionally recognized right to be left alone, to make decisions about one’s own body, and to control one’s own information. In the court decision of Griswold v. Connecticut, the U.S. Supreme Court recognized a constitutional right of privacy.1 This right limits the government’s power to regulate abortion, contraception, and other reproductive issues. The constitutional right to privacy has also been interpreted as permitting the terminally ill (or their legal guardians) to make decisions regarding the termination or withholding of medical treatment to prolong life.

It is important to note that the Constitution is the overriding, or highest, law in the United States. If lower laws (e.g., state or federal laws) conflict with principles in the Constitution, the Constitution overrides the conflicting law. When a law has been struck down because it is “unconstitutional,” that means that the lower law conflicts with the Constitution and is thus invalid.

Federal and state statutes

Laws enacted by legislatures, be they Congress, state legislatures, or local city councils, are another important source of laws that affect health care facilities. One federal law that dramatically affects health care facilities as well as other business is the Americans with Disabilities Act.2 This law not only affects the hiring and employment practices of businesses but also forces public facilities to remove or modify physical plant characteristics that may serve as access barriers for the disabled. The Safe Medical Devices Act is another federal statute that affects all health care facilities.3 It requires that certain incidents that involve medical devices and equipment be reported to a national data bank.

One of the most recent and important federal laws to affect U.S. health care facilities is The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (Public Law 111-5). This law not only puts into place certain incentives for adoption and meaningful use of electronic records, it also substantially affects health information privacy- and security-related practices.

When federal and state laws conflict, valid federal laws supersede the state laws. When state laws and local laws conflict, the valid state law controls.

Rules and regulations of administrative agencies

Among the powers delegated to administrative agencies and departments of the executive branch by legislatures is the power to adopt rules and regulations to implement various laws. These rules and regulations provide instruction in how to comply with the law. Some of the most important agencies and departments at the federal level that affect health care are the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and its Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Food and Drug Administration, the Internal Revenue Service on tax matters, the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission on antitrust issues, and the Department of Labor and the National Labor Relations Board on labor and employment issues.

The rules and regulations of these bodies are valid only if they are within the limits of authority granted to them in their charter. Congress, in passing legislation creating these bodies, decides the broad areas in which these federal agencies may regulate, just as state legislatures do for state agencies. In promulgating their rules and regulations, federal agencies and many state agencies must follow administrative procedure acts passed by the legislature. These acts set forth the steps that administrative agencies must follow in issuing new rules and regulations and deciding disputes about those regulations. The Federal Administrative Procedure Act and most of the states’ acts provide for advance notice of proposed rules and opportunity for public comment. Many federal agencies must publish both proposed and final rules in the daily Federal Register. An HIM professional should be familiar with the Federal Register and with how to scan it for notices of proposed rule making. By doing so, a facility can have early warning of upcoming changes that may affect facility operations. By commenting on proposed rules, the facility can also influence the language of the final rule.

Court decisions (case law)

When cases are brought before them, federal and state courts interpret statutes and regulations, decide their validity, and follow or create common law (also referred to as case law) when no statutes or regulations apply. In deciding cases, courts generally adhere to the principle of stare decisis (let the decision stand). This can be described as following precedent. By referring to similar cases that have been decided in the past and by applying the same principles, courts generally arrive at the same ruling in the current case as in similar previous cases. Sometimes, however, even slight factual differences can result in departures from precedent. Sometimes courts decide that the precedent no longer adequately serves society’s needs. One of the most important examples of this from a health care standpoint was the elimination of the doctrine of charitable immunity, which had until the early to mid-1960s protected nonprofit hospitals from liability for harm to patients. Courts now permit harmed patients to sue hospitals for their wrongful acts. The landmark case on this point is Darling v. Charleston Community Memorial Hospital (Box 14-1).4

As a result, hospitals are held liable for the negligent acts of their employees and, in some circumstances, their physicians. Health care organizations’ liability is discussed in more detail later in the chapter.

Not all disputes are resolved by courts, however. In health care, for example, health care facilities sometimes avoid the need to resort to the courts by participating in mediation or arbitration, also described as alternative dispute resolution, in which a neutral party or panel hears both sides of a dispute and renders a decision, or by settling claims against them by negotiating a direct payment to the parties bringing the claim in exchange for the claimants’ dropping the claim.

The legal system

The court system

Federal courts

The federal court system and many state systems have three levels of courts: trial courts, intermediate courts of appeals, and a supreme court. The federal trial courts are called U.S. district courts. They cannot hear just any case. To be eligible to hear a case, a court must have jurisdiction. To be heard in a federal court, a case must involve either a federal question or diversity of jurisdiction. Federal question cases involve questions of federal law, such as possible violations of federal law or violations of a party’s federal constitutional rights. Diversity cases, which involve citizens of different states, are heard in federal courts, but rather than use federal law, federal judges apply the laws of the applicable states in deciding these cases. In many of these diversity cases, a minimum of $10,000 must also be involved.

Appeals from federal trial courts (U.S. district courts) go to a U.S. court of appeals. The United States is divided into 12 circuits. These courts are typically referred to as the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First (Second, Third, Eleventh, or D.C.) Circuit.

The U.S. Supreme Court is the nation’s highest court. It decides appeals from any of the U.S. courts of appeals. It may also hear appeals from the highest state courts if those cases involve federal laws or the U.S. Constitution. In some instances, if a U.S. court of appeals or the highest state court refuses to hear an appeal, the case may be appealed directly to the U.S. Supreme Court. The U.S. Supreme Court need not and could not possibly hear all cases. Because the Court’s time is limited and the volume of cases is large, the Supreme Court picks and chooses most of the cases it hears. There are no cut-and-dried criteria for which cases are chosen, but the Court attempts to hear the cases involving the most important questions of law or having the greatest potential impact on society. With a few exceptions, the Supreme Court may decide not to review an appealed case. This does not mean that the Supreme Court necessarily approves of the lower court’s decision; it merely means that it chooses not to review the decision.

State and territory courts

In some states, trial courts are divided into special branches that hear certain types of cases. Probate court, traffic court, juvenile court, and family and divorce courts are examples. In addition to these special branches, there are trial courts with general jurisdiction—the power to hear all disputes not otherwise assigned to one of these special branches or not otherwise barred from state courts by law.

The job of the trial court is to hear the facts, review the applicable law, and decide the outcome. Sometimes there are no factual disagreements, but the parties to the lawsuit simply disagree over what the law provides. At other times, there may be no disagreement over the law, but the facts are in dispute. Often a case involves questions of law and facts.

Most states also have an intermediate appellate court that hears appeals from state trial court decisions. These appellate courts do not hold a new trial and hear new evidence; they generally limit their review to the trial court record to determine whether proper procedures were followed and whether the law was correctly interpreted.

Every state has a single high court, usually called the supreme court.* A state supreme court hears appeals from the intermediate appellate court or, if no intermediate court exists, the state trial courts. The high court often has other duties as well, such as formulating procedural rules for the lower state courts to follow.

Roles of the key players: court procedures

The plaintiff is the party who initiates the lawsuit. Plaintiffs initiate suits by filing a complaint, petition, or bill with the clerk of the court. This complaint is a written statement by the plaintiff that states his or her claims and commences the action. Plaintiffs sue one or more defendants, the party or parties from whom relief or compensation is sought. The defendant then files an answer to the complaint, which may also be called a responsive pleading. In this answer, the defendant denies or otherwise responds to the plaintiff’s claims. If the case is not immediately settled, it proceeds into a process of discovery. Sometimes HIM directors are involved in the discovery phase of lawsuits by providing certain information used in the discovery devices described next.

During discovery, each party seeks to discover important information about the case through a pretrial investigation. It includes obtaining pertinent testimony (through depositions, sworn verbal testimony, and through interrogatories, sworn written answers to questions) and documents that may be under the control of the opposing party. For example, a patient who is suing a clinic for negligent care of an infected cut needs to obtain copies of the clinic’s patient records that describe the care that was provided to the patient.

The purpose of the discovery phase is to encourage early out-of-court resolution of cases by acquainting all parties with all pertinent facts. If the case cannot be settled out of court, it proceeds to trial. Evidence properly uncovered during the discovery phase is available in court. The judge is in charge of deciding which laws are applicable and also uses the state or federal rules of evidence (as applicable to the setting) in deciding whether certain pieces of evidence are admissible at trial. Not all evidence produced during the discovery phase is admissible. Often, certain evidence is judged to be unfairly prejudicial to one side or the other or is subject to certain protective laws (such as the laws that protect peer review information in health care organizations). The judge examines the evidence, hears arguments on both sides of the question, and then uses the applicable rules of evidence to decide whether the information can be fairly used at tria.

The judge also keeps order and makes decisions necessary to facilitate a fair, impartial trial. If the case involves a jury, the jury’s job is to determine the facts as presented in court, at least in part by deciding which witnesses and which evidence to believe, and to apply the law as instructed by the judge.

Even when a jury is present, the judge has substantial influence over the trial result. If he or she finds that insufficient evidence has been presented to establish an issue for the jury to resolve, the judge may in various circumstances refuse to send the case to the jury, dismiss the case, or direct the jury to decide the case one way or another. In civil cases, even if the jury has already rendered a verdict, the judge may decide in favor of the other side, setting aside the jury’s verdict. This is called a judgment n.o.v.—judgment non obstante verdicto (notwithstanding the verdict).

Some of the other players involved in trial proceedings are the clerk of the court, court reporter, and bailiff. The clerk of the court is the administrative manager of the court and handles the paperwork associated with lawsuits. Complaints are filed with the clerk, as are other pleadings and documents. The court reporter is responsible for creating a verbatim transcript of court proceedings. Bailiffs are courtroom personnel who are present to assist in keeping order, administering oaths, guarding and the assisting the jury, and performing other duties at the direction of the judge.

Cases that involve health care facilities and providers

Malpractice and negligence

Among the most frequent types of claims made against health care facilities and individual providers are claims of negligence or malpractice (professional negligence). Negligence is conduct that society considers unreasonably dangerous because “first, the [individual or party] did foresee or should have foreseen that it would subject another or others to an appreciable risk of harm, and second, only the magnitude of the perceivable risk was such that the [individual or party] should have acted in a safer manner.”5

At this point, some readers may ask, “How can hospitals be held accountable for actions when they are simply the bricks and mortar within which people work?” Two theories of negligence are used to hold hospitals and other health care organizations accountable for their conduct. Under the first theory, respondeat superior (meaning “let the master answer” for the actions of the servant—the doctrine of “agency”), the legal system imputes the negligent actions of the organization’s employees or agents over whom it has control to the health care organization itself. Using this theory, courts hold employers responsible for the acts of their employees or agents that are performed within the scope of employment. For example, a hospital can be held responsible for the actions of its nurses while they are acting within the scope of their employment (e.g., when they are performing some aspect of their job assignment), but a hospital would not be held responsible for the actions of a nurse in its employ while the nurse is grocery shopping after work.

Under the second, more current theory of corporate negligence, courts can hold health care organizations liable for their own independent acts of negligence. This theory holds organizations responsible for monitoring the activities of the people who function within their facilities, whether those people are employees or independent contractors, such as physicians, and for complying with appropriate industry standards, such as accreditation (the Joint Commission) standards, licensing regulations, and Conditions of Participation issued by Medicare. Health care organizations are no longer considered to be merely physicians’ “workshops.” They retain some responsibility for all who are authorized to function within their facilities (see examples of situations that can lead to malpractice claims against health care organizations and providers).

Malpractice claims are not the only kind of claims against health care organizations and providers. The following are some of the other types of claims that HIM professionals may encounter in their professional careers.

Intentional torts

Intentional tort claims that may be brought against health care facilities include assault and battery, false imprisonment, defamation of character, invasion of privacy, fraud or misrepresentation, and intentional infliction of emotional distress.

When one thinks of assault and battery, one often thinks of a mugging or an attack of some sort. However, an assault is simply a deliberate threat, coupled with the apparent ability, to do physical harm to another person without that person’s consent. No contact is required. For example, if a nurse stood over a patient with a syringe, stating that he or she was going to inject the patient with a strong sedative regardless of whether the patient agreed to it, that would constitute an assault if the patient was aware of the threat. If the nurse proceeded to inject the patient, that would constitute a battery. A battery is nonconsensual, intentional touching of another person in a socially impermissible manner. Awareness of the victim is irrelevant. An unconscious patient who has surgery performed without express (actual) or implied consent (such as when a patient is brought to the facility for life-saving treatment) is the victim of a battery.

Could assault and battery ever really happen in a health care facility? In Peete v. Blackwell, a nurse was awarded damages after a physician with whom she was working struck her and cursed at her while ordering her to turn on suctioning equipment.6 Although there were no lasting injuries, the jury awarded $1 in compensation and $10,000 in punitive damages.

The laws concerning battery are one of the prime reasons behind the requirement to obtain the patient’s written consent to treatment. Allegations of battery against health care facilities most often involve situations in which improper or no patient consent was obtained before a surgical procedure. Regardless of whether the procedure helps or harms the patient, invasions of the patient’s person without consent entitle the patient to at least nominal damages.**

False imprisonment is unlawful restraint of a person’s personal liberty or the unlawful restraining or confining of a person. Physical force is not required; all that is required is a reasonable fear that force will be used to detain or intimidate the person into following orders. How could this apply to a health care facility? If a facility tried to prevent a patient’s departure from the facility until the patient’s bill was paid, this could qualify as false imprisonment. The use of physical restraints to keep a patient in bed for no other reason than inadequate staffing available to monitor patients could also qualify.

False imprisonment issues can be complex. For example, if an intoxicated driver involved in a motor vehicle accident is treated for minor cuts in an emergency department and now wants to be discharged to drive home but is still extremely intoxicated, must the facility release that patient, or may he or she be restrained until capable of driving safely? Statutes in some states permit intoxicated or mentally ill people to be detained by a hospital if they are dangerous to themselves or others. This is one example of why it is so important for the staff in health care organizations to be familiar with state laws. In judging reasonableness of a health care provider’s actions in detaining a patient, documentation in the patient record is often vital.

Defamation of character is oral (slander) or written (libel) communication to a person (other than the person defamed) that tends to damage the defamed person’s reputation in the eyes of the community. To succeed in a defamation action, the defamed person must show that there was communication to a third party. Truth of the statements is a defense, as is privilege. If the defamation occurs during a privileged communication—such as during confidential communications between spouses or in a talk with a priest or minister—defamation is not found as long as the statements are made without malice (evil intent). Defamation cases in health care are unusual, but they do occur, especially in the context of medical staff credentialing and granting of privileges, when the defamed party argues that the defamatory remarks were made with malice. Professionals who are called incompetent in front of others generally have a right to sue to defend their reputation. If the person making the remark cannot prove that the comment is true or that some other privilege applies, he or she may be held liable for damages. For that reason, it is generally wise to refrain from making disparaging remarks about other health professionals and colleagues.

Invasion of privacy is an intentional tort with which HIM professionals must be concerned. By the very act of submitting to treatment, patients give up some privacy. However, negligent disregard for patients’ privacy can and does result in actions against health care providers and organizations, and it can also result in regulatory penalties such as fines for violations of those regulations, and even criminal penalties. This is discussed later in the chapter. Because HIM professionals and other health professionals work with sensitive information on an almost constant basis, it is easy to become callous to privacy issues. Readers who have visited friends or family members in the hospital and overheard staff members talking casually about patients and their conditions in hallways, elevators, and the cafeteria have witnessed what may have been an invasion of privacy or breach of confidentiality. Health care providers who divulge confidential information from a patient’s record to an improper recipient without the patient’s permission have invaded the patient’s privacy and breached their duty of confidentiality. A great deal of this chapter is devoted to identifying what health information is confidential and who is a proper or an improper recipient. HIM professionals must learn these principles well and become expert in applicable state and federal laws so that they not only avoid violating patients’ privacy themselves but also can help other health professionals understand how to respect patients’ privacy and confidentiality rights.

Fraud is a willful and intentional misrepresentation that could cause harm or loss to a person or the person’s property. In addition to fraud associated with improper billing for procedures not performed or deliberately coding incorrectly to gain a higher payment (criminal fraud), fraud can occur in health care facilities when a physician promises a certain surgical result, although he or she knows that the result is not so certain. For example, a physician who promises that there is no chance of a complication resulting from plastic surgery, although such complications can occur, is guilty of misrepresentation.

Intentional infliction of emotional or mental distress can also result in claims against health care facilities. In a 1975 case, a court found that a physician and hospital (through its employees) were guilty of intentional infliction of emotional distress. In this case, the mother of a premature infant (who died shortly after birth) had gone to her physician for a postpartum checkup.7 She noticed a report in her medical record stating that the child was past 5 months’ gestation and therefore could not be disposed of as a surgical specimen. On questioning her physician about what had happened to the body, the physician told his nurse to take the mother to the hospital. At the hospital, the mother was taken by a hospital employee to a freezer. The freezer was opened, and the mother was handed a jar containing her baby. The mother was awarded $100,000 damages, upheld on appeal. The cases are not always so dramatic. In 1985, a Georgia court found a physician guilty of intentional infliction of emotional distress for yelling at a patient and her husband.8

Products liability

Products liability cases sometimes involve health care facilities. Products liability is the liability of a manufacturer, seller, or supplier of a product to a buyer or other third party for injuries sustained because of a defect in the product. The injured party may sue the seller, manufacturer, or supplier. If, for example, a hospital improperly processes or stores blood in its own blood bank, it may be liable to any patient who is harmed as a result. If the staff of a research hospital designs a new type of medical equipment that is tested on patients, any harm resulting from product defects can result in product liability claims. Products liability is a complex subject beyond the scope of this chapter. It is included here simply as a reminder that there are many potential sources of liability for today’s health care organizations.

Contractual disputes

Breach of contract is a common claim in litigation that involves health care providers and organizations. Typically, the claims arise when one party to a contract fails to follow the terms agreed to in the contract. Interestingly, courts have been willing to enforce ethical standards prohibiting breach of confidentiality (such as the American Hospital Association’s [AHA’s] patient right’s statement titled The Patient Care Partnership: Understanding Expectations, Rights and Responsibilities, and ethical standards of the American Medical Association) as part of a contractual relationship between health care providers and their patients. Thus, improper disclosure of health information can give rise to a breach of contract claim and an invasion of privacy or breach of confidentiality claim. (Invasion of privacy and breach of confidentiality claims are discussed later in this chapter.) In an important case on this subject, Hammonds v. Aetna Casualty and Surety Co., the court found that a physician breached an implied condition of his patient–physician contract when he disclosed health information to a hospital’s insurer without the patient’s authorization.9

Antitrust claims

Although such claims have decreased in recent years, health care providers and organizations have been targets of antitrust claims. Most of these claims revolve around mergers and acquisitions and alleged anticompetitive behavior in medical staff credentialing activities. For example, if the obstetricians on the medical staff of a local hospital seek to remove an obstetrician’s staff privileges so that there is less competition for patients, that hospital may find itself entangled in an antitrust suit. These suits usually do not directly involve the HIM department or service, but sometimes HIM professionals are involved to the extent that they support the medical staff’s peer review and credentialing functions.

Crimes and corporate compliance

Criminal activity can take place in any health care facility. A nurse practicing in a hospital is probably able to tell of mysterious discrepancies in narcotic counts (counts done on each unit that stores narcotics to ensure that no drugs are missing). Angel-of-death murder scenarios have been sensationalized in books and television, but they have their basis in actual events in which the weak and ill have become prey for criminal or deviant behavior by facility employees. For example, in 2004, Charles Cullen, a registered nurse, pled guilty to the murder of 29 patients he had cared for at various health care facilities. Patient abuse and sexual improprieties are also terrible phenomena that can occur in health care facilities. In addition, falsification of business or patient records (e.g., by billing Medicare for patients not seen or services not performed, or by deliberately assigning incorrect codes to maximize payment) may be grounds for criminal indictment.

Concerns about improper billing practices have led to the passage of laws and regulations targeting health care providers who submit false claims, engage in fraudulent coding practices, and otherwise fail to comply with statutory and regulatory mandates. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (Public Law 104-191; HIPAA), the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (Public Law 105-33), and even the Federal False Claims Act (1863, with 1986 amendments) and its subsequent interpretation by the DHHS are examples of laws imposing penalties—up to and including criminal sanctions—against health care providers who engage in fraudulent practices.

The growth in prosecution against health care providers has led to a profound interest (and need) among provider organizations in developing corporate compliance plans with the goal of preventing, detecting, and resolving wrongdoing in health care organizations. Ideally, the compliance program not only discourages unlawful activity but also promotes a culture in which suspected problems can be safely raised internally, preventing the need for “whistleblowers” to go to outside regulatory bodies to raise concerns. These whistleblower-based prosecutions, called qui tam prosecutions, have been particularly attractive to employees (disgruntled or otherwise) because the whistleblower is entitled to a share of the government’s winnings in these cases. Health care leaders have recognized the sense of solving suspected problems internally and rapidly.

The health care organization’s compliance plan should focus on all areas of regulatory compliance, with special emphasis on preventing fraudulent coding and billing practices. The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) of the DHHS has issued model compliance plans for various types of health care organizations (such as clinical laboratories and hospitals), which provide organizations with a logical starting point in developing their own corporate compliance plans. The OIG also issues periodic advisory opinions and fraud statistics to show its prosecutorial priorities, which is useful to health care organizations in planning their own fraud prevention efforts. In addition, the American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA) has published numerous articles on the subject, a model Health Information Management Compliance Program, and a practice brief that is available on AHIMA’s Web site. Common to all compliance programs is the need to address and establish internal standards of conduct, education for staff on compliance, regular auditing of coding and billing practices, continual monitoring of practices, and methods of further developing and updating the organization’s plan.

Issues germane to the HIM professional take center stage in these compliance plans. Not only must HIM professionals be concerned with accurate coding and billing, they must also focus on other areas of regulatory compliance, such as ensuring the confidentiality and security of health information. HIM professionals must also guard against outside contracts with vendors containing terms that could lead to risks of noncompliance.

Noncompliance with statutes, rules, and regulations

As mentioned earlier, health care organizations that fail to follow government-imposed mandates run the risk of a variety of potential penalties, including monetary or criminal penalties, removal from participation in the Medicare program, and even loss of licensure.

With this information as a backdrop, the remainder of this chapter looks at the most common legal obligations and risks that face health care facilities, health care providers, and HIM professionals in particular. First, which legal obligations and risks involve HIM professionals most directly?

Legal obligations and risks of health care facilities and individual health care providers

Duties to patients, in general

Patients have numerous rights associated with their health care. Some of these rights are discussed in detail in this section. Laws, rules, or regulations establish some rights; others are based on ethical codes and even the federal Constitution. Beyond the specific rights discussed in the following, HIM professionals should be aware of patient rights granted in the AHA’s patient rights statement discussed earlier, the Ethics, Rights and Responsibilities chapter of the accreditation manuals issued by the Joint Commission, and specific laws governing access to care, such as the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA; 42 USC 1395 dd). The EMTALA imposed new obligations on health care facilities to provide medical screening examinations and stabilizing treatment to patients before transferring them to other facilities. The purpose of the law was to reduce inappropriate transfers (such as those done primarily for financial reasons when the patient has no insurance) that put the patient at risk of harm. The net effect of these various bills or rights, codes of conduct, and laws has been to alert patients to their rights and to provide remedies when their health care providers fail to respect those rights. We are entering the era of empowered health care consumers. This should lead to more interaction between patients and the HIM department as patients seek more information about their care and treatment.

Duty to maintain health information

One of the most fundamental duties that involve HIM professionals and their health care facility employers is that of maintaining health information about patients. This duty is imposed explicitly by state and federal statutes and regulations as well as accreditation standards. In some states, the hospital licensing statutes specify not only that a medical record must be kept for every patient but also what that record must contain at a minimum. Failure to meet the requirements of these licensing statutes could subject a facility to loss of licensure and closure. The law and regulations setting forth the Conditions of Participation in federal payment programs such as Medicare also require that medical records be kept, and they outline in broad terms what those records must include.10 Accreditation standards of the JCAHO also require accredited facilities to maintain medical records, and the HIPAA privacy rule also speaks to what documents must be maintained for patient access and use as part of a designated record set. (DRS)—defined in that rule as a group of records maintained by or for a covered entity, as follows:

Patients must be able to access that information for at least 6 years, and even longer if state or other federal laws require longer retention periods.

The duty to maintain health information is also implied in other laws. For example, vital statistics laws require the reporting of births and deaths. Under federal and state statutes, health care facilities must report to various data banks certain disease conditions and medical events, such as the treatment of gunshot wounds, suspected child abuse, elder abuse, industrial accidents, certain poisonings, abortions, cancer cases, and communicable diseases.

Mandatory reporting requirements vary from state to state. These statutes have in common that reporting is required and the authorization of the patient is generally not needed. In fact, even if the patient expresses the wish not to have information released, the health care organization must comply with the reporting requirement. This tension between the reporting statutes and confidentiality often arises with state requirements for reporting actual or suspected child abuse. Reports made in error admittedly cause much pain and embarrassment for the family involved. Many states, recognizing the natural reluctance of people to make such reports when the abuse is not proved, have exempted the party making the report from liability for erroneous reports as long as the report is made in good faith (in other words, without malice or evil intent).

The reporting statutes attempt to encourage reporting in another important way. For example, failure to report child abuse can result in liability for injuries a child later sustains when discharged home to the suspected or actual abuser.

The problem becomes even stickier when mandatory reporting statutes conflict with other laws, such as state laws that bar disclosure of mental health treatment records and federal laws that bar disclosure of substance abuse treatment. If in the course of therapy a child or an elderly person indicates that he or she has been abused, what must the therapist do? Some court decisions have permitted the protection of these confidentiality laws to be circumvented, but only to the extent necessary to fulfill the requirements of the reporting statute.11 In addition, some state confidentiality laws permit exceptions in cases of imminent harm, in which the child or abused party is in immediate danger. Other statutes, however, do not provide convenient solutions to this problem. HIM professionals who face such a situation should consult legal counsel, who may seek direction from the court in reconciling all the interests involved.

These examples illustrate why compliance with mandatory reporting statutes is not always as simple as it may seem. HIM professionals must determine their state’s requirements and how those requirements may conflict with other confidentiality obligations so that appropriate reporting procedures are in place.

Duty to retain health information and other key documents and to keep them secure

Just as there are requirements to create patient records, there are also requirements to retain that information. Health care facilities take guidance from federal and state record retention laws and regulations and from state statutes of limitations in setting their own record and information retention policies. Facilities must also take into account the uses of and needs for that information, the space available for hard copy storage if the records include paper, and the resources available for microfilming, creating optical disks, or electronic storage. In addition, there are evidentiary considerations in record retention, including most recent amendments to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure for the preservation of electronically stored information (referred to as “e-discovery rules”). Remember, however, that record retention regulations and rules are only a baseline; in other words, facilities must meet these minimum retention periods but may establish longer retention schedules if desired.

It is not enough simply to keep these records. HIM professionals must ensure that the records are kept in a way that minimizes the chance of their being lost, destroyed, or altered. Plaintiffs have won negligence suits against facilities that failed to safeguard their records from loss or destruction.12 Security of health information has taken on new and more complex dimensions as more and more health information is stored in various electronic and other media. Medical records security used to be a relatively straightforward matter of controlling access to the areas where paper records were kept and having adequate safeguards against physical threats such as fire, flood, and severe weather. Now, with each new form of data storage and retrieval technology, HIM professionals must be alert to the new security threats that may accompany those technologies.

HIPAA security regulations, which went into effect in 2005, will assist in avoiding those security threats. In 1996, Congress passed the act commonly referred to as HIPAA. As part of that act, Congress added a new section to Title XI of the Social Security Act, titled “Administrative Simplification.” The purpose of the Administrative Simplification amendment was to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the health care system by stimulating the development of standards to facilitate electronic maintenance and transmission of health information. The act directed the secretary of DHHS to adopt standards for electronically maintained health information and standards for electronic signatures and other matters such as unique health identifiers and code sets.

The standards, which went into effect in April 2005, apply to health care providers, health plans, and health care (data) clearinghouses.

Certain administrative procedures, physical safeguards, and technical security services and mechanisms are required under these regulations. Those obligations have been extended not only to the entities covered by HIPAA but also to their business associates, through a new provision within ARRA. See Chapter 8 for an in-depth discussion of security safeguards. The regulations apply to all electronically maintained health information in health care organizations, and it is important for HIM professionals to become familiar with the final standards.

Health information is valuable only if it is accurate, complete, and available for use when needed. Therefore, HIM professionals must design safeguards that not only protect the information from loss or destruction and prevent the corruption of electronically stored data from power losses or surges but also protect the integrity of the information itself. In other words, the information must be protected from inappropriate alteration.

Why would anyone want to alter health information or documentation in a patient’s record? In some situations, such as when a health professional is sued for malpractice, he or she may be tempted to alter the record to make the documentation appear more complete than it originally was. Some health professionals have not yet learned the importance of thorough contemporaneous documentation (i.e., documentation made while care is being provided, while the information is fresh in the care provider’s mind), and as a result, when the time comes to defend the provider’s actions, the record may not reflect the care of the patient in a positive light. HIM professionals must guard against inappropriate alterations to health information by controlling access to records with extra precautions for records that are involved in litigation. If presented with a request to make a change to a patient record involved in litigation, an HIM professional should refer that request to the facility’s defense counsel. Rather than “improving” the documentation, a health professional who makes later alterations often ends up harming the case because the plaintiff’s attorney may have already gotten a copy of the original, unaltered record from the patient before filing suit. Imagine how it might appear to a jury if the plaintiff’s attorney can show that the defendant altered the record when the suit was filed and that the health facility took no steps to protect the record from alteration.13 For these reasons, it is wise to supervise all access to patient records that are involved in litigation. By doing so, the integrity of the record can be maintained while appropriate access is permitted.

Falsification of records can lead to other problems as well. In some states, it is a crime if it is done for the purpose of cheating or defrauding and may lead to sanctions against health professionals’ licenses.

Error correction

Errors that are made in documenting information must be corrected as soon as they are detected with use of proper error correction methods. These methods should be outlined in the facility’s policy and procedure manual and taught to all people who document patient health information.

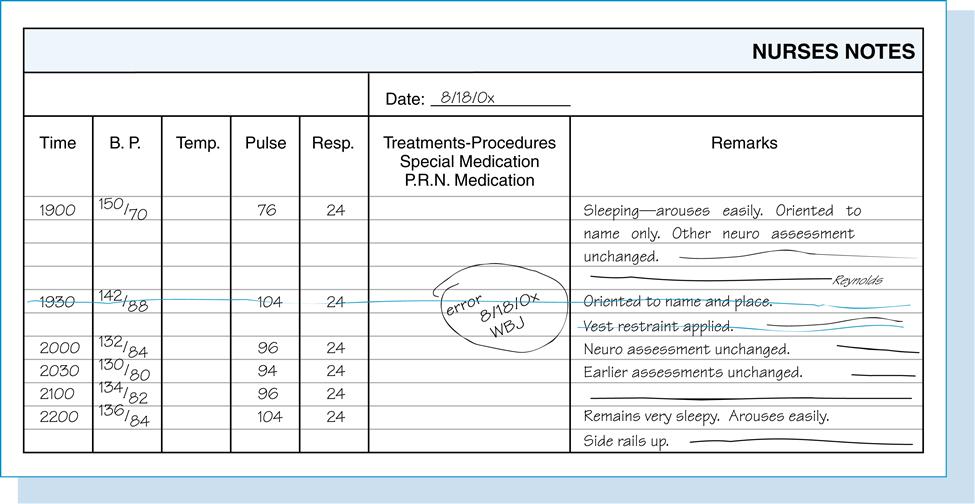

Generally, the person who made an error should correct it. If the correction is a major one (e.g., erroneous laboratory results were entered on the record and resulted in a problem in the patient’s care), the person making the correction should consult the HIM manager, risk manager, and perhaps even facility legal counsel to ensure that the correction method complies with facility policy and that all appropriate steps that need to be taken are followed. Most corrections are not so dramatic. A nurse begins to chart patient A’s information on patient B’s record but instantly realizes the error. Or, in the course of making up a new medication administration record, the unit clerk misspells the name of a medication and the nurse who double-checks the record quickly catches it. In situations that involve paper-based health information, the person making the error should simply draw a single line through the incorrect entry, enter the correction and initial it, and note the time and date of the correction (Figure 14-1). Under no circumstances should the original entry be erased, scribbled over, or hidden, because an obliteration can raise suspicion in the minds of jurors about the original entry and whether it is an attempt to cover up a major problem.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree