Performance management and patient safety

Patrice Spath and Donna J. Slovensky

Objectives

• Define key quality management and patient safety terminology.

• Describe the primary stakeholders in health care quality and patient safety.

• Differentiate among structure, process, and outcome measures of performance.

• Discuss various approaches used by health care organizations to improve quality and patient safety.

• Describe and apply improvement tools frequently used in problem analysis and performance management.

• Describe the process of conducting a root cause analysis.

• Describe the process of conducting a proactive risk assessment.

• Identify key risk management and utilization management activities in health care organizations.

Key terms

Accreditation

Adverse event

Affinity diagram

Aggregate data

Baldrige National Quality Award

Bar graph

Benchmarking

Brainstorming

Case management

Cause-and-effect diagram

Checksheet

Claims Management

Clinical practice guidelines

Concurrent review

Conditions of Participation

Control chart

Correlation analysis

Credentialing

Credentials verification organization

Data sheet

Decision matrix

Discharge planning

Electronic health record

Evidenced-based medicine

External benchmarking

Failure mode and effect analysis

Federal Register

Fishbone diagram

Flowchart

Force field analysis

Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set

Health care integrity data bank

Histogram

Incident report

Indicator

Intensity of service/severity of illness

Internal benchmarking

Lean thinking

Leapfrog Group

licensed independent practitioners

Line graph

Loss reduction

National Practitioner Data Bank

National Quality Forum

Never events

Nominal group technique

Outcome measures

Pareto chart

Patient advocacy

Patient safety improvement

Patient safety indicators

Pay for performance

Peer review

Performance assessment

Performance measure

performance target

Physician advisor

Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA)

Potentially compensable event

Proactive risk assessments.

Prospective review process

Privilege delineation

Process measures

Retrospective review

Quality improvement

Quality improvement organizations

Rapid cycle improvement

Reliable measure

Risk

Risk management

Root cause analysis

Run chart

Sentinel event

Simulation

Six Sigma

Statement of work

Statistical process control

Structure measures

The Joint Commission

The National Committee for Quality Assurance

Threshold

Utilization management

Value chain

Abbreviations

AHRQ—Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

CMS—Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

COP—Conditions of Participation

DMAIC—Definition, Measurement, Analysis, Improvement, and Control

EBM—evidence-based medicine

EHR—electronic health record

FMEA—failure mode and effect analysis

HCO—health care organization

HEDIS—Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set

HIM—health information management

IOM—Institute of Medicine

IS/SI—intensity of service/severity of illness

LIP—licensed independent practitioner

NCQA—National Committee for Quality Assurance

NICU—neonatal intensive care unit

NPDB—National Practitioner Data Bank

NPSD—network of patient safety databases

NQF—National Quality Forum

P4P—Pay for Performance

PCE—Potentially Compensable Event

PDCA—Plan, Do, Check, Act

PDSA—Plan, Do, Study, Act

PSI—Patient Safety Indicator

PSO—Patient Safety Organization

QI—Quality Improvement

QIO—Quality Improvement Organization

RCI—Rapid Cycle Improvement

SCIP—Surgical Care Improvement Project

SOW—Statement of Work

TJC—The Joint Commission

UM—Utilization Management

Student Study Guide activities for this chapter are available on the Evolve Learning Resources site for this textbook. Please visit http://evolve.elsevier.com/Abdelhak.

When you see the Evolve logo  , go to the Evolve site and complete the corresponding activity, referenced by the page number in the text where the logo appears.

, go to the Evolve site and complete the corresponding activity, referenced by the page number in the text where the logo appears.

Most people expect quality in the delivery of health care services. Consumers expect to receive the right medical interventions, achieve good outcomes, and to be satisfied with personal interactions with caregivers. Additionally, consumers expect the physical facilities where care is provided to be clean and pleasant and to have the “best” technology available. Each of these characteristics is a part of quality; none is the whole. The way a health care consumer defines quality may differ from what providers or purchasers view as important quality attributes.

Without question, “quality” should be an integral component of all health care services. Despite this universally accepted belief, how to measure performance and what constitutes an acceptable level of quality continue to be greatly debated. Scholars and researchers, health care providers and payers, and individual consumers of health care all bring different perspectives into the debate.

In the past few years, the public has become increasingly concerned about the safety of health care services. Media reports about errors made in the delivery of patient care have raised consumer awareness of the potential for medical mishaps. In November 1999, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released the report, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System.1 The report purported to show, for the first time, the extent to which medical errors may cause preventable deaths in the United States. It was estimated that between 44,000 and 98,000 deaths occur each year in hospitals as a result of medical errors by physicians, pharmacists, and other health care providers. The lower estimate, 44,000 deaths, places medical errors as the eighth leading cause of death in the United States, whereas the higher estimate, 98,000 deaths, places medical errors as the fifth leading cause of death in the United States. The IOM report suggested that most medical errors are a result of the complexity of health care services, not incompetent individuals.

In the 2001 IOM report Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century,2 the Committee on Quality of Health Care in America identified six key dimensions of health care quality:

Safe—avoiding injuries to patients from the care that is intended to help them.

Effective—providing services based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit and refraining from providing services to those not likely to benefit (avoiding underuse and overuse, respectively).

Patient centered—providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.

Timely—reducing waits and sometimes harmful delays for both those who receive and those who give care.

Efficient—avoiding waste, including waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy.

Equitable—providing care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, geographic location, and socioeconomic status.

The big picture and key players

Although health care providers have numerous internal incentives for improving the quality and safety of services, the details for accomplishing these activities are often influenced by external mandates. Some requirements are grounded in law; others are stipulated by agencies with which a health care organization (HCO) interacts on a voluntary basis. Purchasers and consumers also play a role in influencing performance management in health services. This section focuses on the key players and how these groups affect health care quality and patient safety.

Federal oversight agencies

Because most HCOs provide services to Medicare or Medicaid beneficiaries, the regulations of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have significant impact on the “what” and “how” of performance improvement activities at the provider level. Regulations governing providers of services to Medicare beneficiaries are detailed in the Conditions of Participation (COP). These regulations require that providers develop, implement, and maintain an effective organization-wide, data-driven quality assessment and performance improvement program. The regulation specifics vary according to the provider setting. For instance, hospitals must measure, analyze, and track quality indicators, including adverse patient events, and other aspects of performance that assess processes of care, hospital service, and operations.3

CMS also conducts nationwide health care performance measurement, with providers required to submit measurement data to CMS. Current measures and measurement results can be found on the Medicare Web site. CMS contracts at the state level with quality improvement organizations (QIOs) to direct and oversee improvement initiatives. Requirements for QIOs that contract with CMS are outlined in comprehensive triennial documents, the QIO Statement of Work (SOW) numbered consecutively beginning in 1983. The Ninth SOW, encompassing August 1, 2008, through July 31, 2011, includes initiatives related to reporting of quality measures, improving surgical care and management of medical patients, reducing hospital readmissions and improving patient transitions between health care settings. The current SOW is available on the CMS Web site.

Accrediting bodies

Many health care organizations voluntarily participate in national accreditation programs. Accreditation is a credential given to an organization that meets defined standards, some of which relate to performance management. Only organizations seeking accreditation must comply with these mandates. All health care accreditation programs include some requirements related to performance management. The requirements of two groups, the Joint Commission and the National Committee for Quality Assurance, are summarized in the following section.

The joint commission

The Joint Commission (TJC) is a not-for-profit, nongovernmental entity that offers voluntary accreditation programs for all types of health care facilities. It provides education, leadership, and objective evaluation and feedback to health care organizations in the quest for health care quality and patient safety. The TJC standards require accredited organizations to collect data to monitor performance, compile and analyze performance data, and improve performance.

Since 2002, TJC has sponsored a comparative performance measurement project that involves collection and analysis of data received from accredited hospitals. The initial core measure data focused on hospital performance in four areas: acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, community-acquired pneumonia, and pregnancy and related conditions. A hospital’s actual performance in these areas is one of the elements taken into consideration by TJC when accrediting the organization. As with all regulations in health care, TJC standards are subject to change. Current performance measurement and improvement initiatives, accreditation issues, and other information are available on TJC’s Web site.

National committee for quality assurance

The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) is a private, not-for-profit organization established in 1991. NCQA accredits a variety of organizations from health maintenance organizations to preferred provider organizations to managed behavioral health care organizations, and each accreditation program has distinct performance management requirements. More than 100 million Americans (70.5% of all health plan members) are covered by an NCQA-Accredited health plan.4 NCQA also sponsors the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), a comparative performance measurement project that evaluates a health plan’s clinical and administrative systems. These data are made available to purchasers and consumers to assist them in making choices about health care providers.

NCQA accreditation and participation in HEDIS is voluntary, but many large employers require or request accreditation or HEDIS reporting for the health plans they make available to their employees. Additional information about the NCQA’s programs and activities is available on their Web site.

National quality awards

Some health care leaders seek to advance performance improvement by voluntarily participating in quality award programs at the state and national levels. An example of such a program is the Baldrige National Quality Award, established by Congress in 1987 to recognize organizations for their achievements in quality and business performance and to raise awareness about the importance of quality and performance excellence as a competitive edge. The Baldrige Healthcare Criteria for Performance Excellence, first published in 1998, are intended to help organizations use an integrated approach to organizational performance management that results in5:

The Baldrige Healthcare Criteria are designed as an interrelated system of items that address major areas of performance excellence. The 2009 criteria included 19 items, organized into seven categories or management disciplines that cover5:

The Baldrige Criteria help HCOs stay focused on improvement goals and align all activities to achieve these goals. The criteria are the basis for many national quality award programs sponsored by professional organizations. An example is the American Health Care Association’s Quality Award that addresses the key requirements of performance excellence in long-term care facilities. The criteria for the American Hospital Association Quest for Quality prize cover many of the concepts found in the Baldrige Criteria.6 Information about the Baldrige Award and the criteria underpinning it is available on the National Institute of Standards and Technology Web site.

Purchasers

Federal and state governments are by far the largest purchasers of health care services. The quality of these services is regulated by the COP and by state health department regulations. There are also many private health insurance companies, as well as employers that purchase health insurance for their employees, that have a vested interest in health care quality. Like federal and state governments, these purchasers want to receive good value for the dollars they expend on health care services. In response to the rising cost of health care, nongovernment health care purchasers are taking a more assertive role in advancing quality and patient safety.

The Leapfrog Group, a collaboration of large employers, came together in 1998 to determine how purchasers could influence the quality and affordability of health care. The Leapfrog Group identified three hospital quality and safety practices that are the focus of its health care provider performance comparisons and hospital recognition and reward. The quality practices are:

• computerized physician order entry

• evidence-based hospital referral

• intensive care unit staffing by physicians experienced in critical care medicine

More information about the Leapfrog Group initiatives can be found on its Web site.

Some health plans have initiated payment systems that financially reward providers who achieve specific quality or patient safety goals. These initiatives are commonly called Pay for Performance (P4P). The fundamental principles of P4P are (1) common performance measures for providers (usually represent a balance of patient satisfaction, prevention, and long-term care management) and (2) significant health plan financial payments on the basis of that performance, with each plan independently deciding the source, amount, and payment method for its incentive program.

In 2008, the CMS announced that Medicare will no longer pay hospitals a higher rate for an inpatient stay if the reason for the enhanced payment is a “never event.” Never events are hospital-acquired conditions considered by CMS to be (1) preventable, (2) high cost or high volume (or both), and (3) result in additional costs. Never events include7:

• Foreign object retained after surgery

• Stage III and IV pressure ulcers

• Injury following falls and other trauma

• Catheter-associated urinary tract infection

• Vascular catheter–associated infection

• Certain manifestations of poor control of blood sugar levels

• Deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism following total knee replacement and hip replacement

Consumers

Consumers do not have the power to mandate specific health service performance management activities; however, they do influence what is required by federal regulations and accreditation standards. This influence occurs in many ways. There are numerous consumer/patient advocacy groups that work in partnership with legislators, providers, and purchasers to promote health care quality and patient safety improvements. Often one or more consumer representatives serve on the governing board or advisory groups of accreditation organizations to provide the “public perspective” when accreditation standards are revised. Individuals and consumer groups have the opportunity to comment on proposed changes in the Medicare COP, which are published in the publicly available Federal Register.

Patient advocacy services may be available in individual HCOs as a proactive approach to ensuring patient satisfaction with the process and outcomes of care episodes. In addition to responding to individual patient complaints, HCOs often monitor overall patient satisfaction with the facility and with staff interactions by use of written questionnaires or telephone surveys. Hospitals that care for Medicare patients are required to participate in the CMS patient satisfaction measurement system.8 Satisfaction survey results for individual hospitals are publicly available on the Medicare Web site.

National health care quality measurement priorities

During the 1990s, great emphasis was placed on the need for public accountability of providers and insurers to furnish comprehensive, high-quality health care at an acceptable cost.9 In support of public accountability, the National Quality Forum (NQF) was created in 1999 to develop and implement a national strategy for health care quality measurement and reporting. The NQF, a not-for-profit membership group, includes representatives from a diverse group of national, state, regional, and local organizations, including purchasers, consumers, health systems, health care practitioners, health plans, accrediting bodies, regulatory agencies, medical suppliers, and information technology companies. The mission of the NQF is to improve American health care through endorsement of consensus-based national standards for measurement and public reporting of health care performance data that provide meaningful information about whether care is safe, timely, beneficial, patient centered, equitable, and efficient. The specific goals of the NQF are as follows10:

• set national priorities and goals for performance improvement

• endorse national consensus standards for measuring and publicly reporting on performance and

• promote the attainment of national goals through education and outreach programs

At this time, the NQF has endorsed several condition-specific performance measure sets that address the quality of patient care across the continuum. For instance, sets of measures that can be used to evaluate the quality of hospital care cover conditions such as the following:

Many of the condition-specific measures in the NQF endorsed measure sets are being used by CMS, TJC, NCQA, and other accrediting and regulatory groups to evaluate the performance of HCOs. Information about the work of the NQF and the measure development and dissemination process can be found on the NQF Web site.

Although there are numerous factors influencing health care performance management and differing stakeholder incentives and priorities, the fundamental elements are constant: performance measurement, assessment, and improvement. These are the basic building blocks of performance management. To promote a systematic organization-wide quality management approach, providers may have a written performance management plan. This plan describes the organization’s structure and processes for measuring, assessing, and improving performance.

As the health care delivery system struggles to achieve a balance between costs and access, performance management and clinical outcomes become increasingly important. HCOs and other players in the industry will inevitably compete in terms of quality. Orme11 succinctly describes the goals of quality improvement (QI) efforts in health care as “to improve the processes of delivering care and thereby increase customer satisfaction with the quality of care (service outcomes), to improve the functional health of patients (clinical outcomes), and to reduce the costs of providing care.”

Performance measurement

Performance measure is a generic term used to describe a particular value or characteristic designated to quantify input, output, outcome, efficiency, or effectiveness. Input refers to the materials or resources used in a process, such as x-ray film and the radiographer’s time. Output is the product of a process, such as a transcribed record document or a completed diagnostic test. Outcome is the end results of a process, such as a “complete” health record or a patient’s satisfactory physical condition after a surgical procedure. Efficiency refers to “doing things right,” or using an acceptable ratio of resources used to output or outcome achieved. Five ruined films before an acceptable diagnostic image is achieved would not be considered efficient! Effectiveness refers to “doing the right thing.” For example, using only the appropriate diagnostic tests to establish a treatment plan that returns a patient to a state of wellness is effective.

In recent years, medical professionals have increasingly relied on evidence-based medicine (EBM) to select the “right thing” to do for a patient. EBM involves the use of current best research evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. This research is incorporated into clinical practice guidelines—statements of the right things to do for patients with a particular diagnosis or medical condition. Hundreds of examples of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines can be found on the Internet at the National Guideline Clearinghouse sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Performance measures are composed of a number and a unit of measure. The number provides the magnitude (how much), and the unit is what gives the number its meaning (what). For example, “Percent of patients undergoing hip replacement surgery who receive prophylactic antibiotics as specified by the treatment protocol” is an example of a performance measure. Performance measures are often described as “indicators.” An indicator is a quantitative measure of an aspect of patient care. It is not a direct measure of quality; rather, it is a screen or flag that indicates areas for more detailed analysis. For instance, a low percentage of patients receiving the correct antibiotic is an indication that antibiotic prescribing practices need to be examined more closely.

Performance measures are typically classified as one of two types: important single events or patterns of events evident in aggregate data. An important single event is an infrequently occurring, undesirable happening of such magnitude that each occurrence warrants further investigation. Examples are unexpected obstetrical death, severe transfusion reaction, and surgery on the wrong body part. When an important single event occurs, there is an immediate investigation to determine the cause and to initiate corrective actions to prevent the event from recurring. These events, often referred to as sentinel events, are discussed in greater detail in relation to patient safety.

The second type of measure (patterns evidenced in aggregate data) reflects performance that is less dramatic or injurious than an important single event and can reasonably be expected to fluctuate. For example, hospital meal trays delivered late or delayed administration of medication are undesirable events but can be expected to occur occasionally in the normal course of operations. Typically, these types of events are monitored until performance levels trigger a predetermined threshold. At that point, a focused review is undertaken to initiate corrective action. For instance, a hospital monitoring compliance with the use of prophylactic antibiotics for patients undergoing hip replacement surgery might set a performance expectation of 95% or better. When actual performance falls below 95%, a focused review is conducted to determine the cause of less-than-desired results.

To evaluate the quality of health services adequately, the performance of many aspects must be measured.

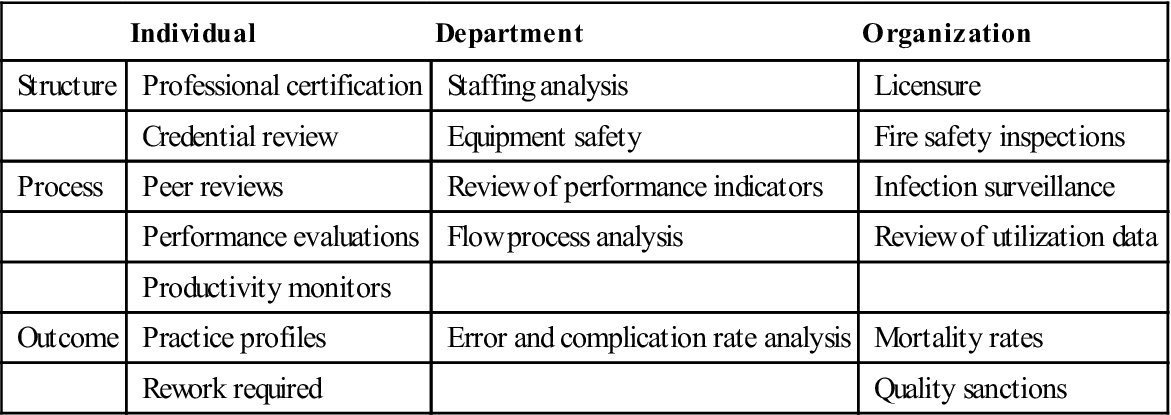

Structure, process, and outcome measures

Avedis Donabedian, physician and professor of public health at the University of Michigan from 1966 to 1989, was internationally known for his research on health care improvement. His work in the definition and assessment of health care quality resulted in one of the most widely acknowledged models for measuring quality in health care.12 Donabedian defined a comprehensive approach to assessing quality of care by using measures that examine structures, processes, and outcomes associated with the delivery of health care. Table 12-1 contains examples of structures, processes, and outcomes frequently measured for the purpose of evaluating performance of individuals, departments, and the organization as a whole.

Table 12-1

DONABEDIAN’S MODEL OF STRUCTURE, PROCESS, AND OUTCOME

| Individual | Department | Organization | |

| Structure | Professional certification | Staffing analysis | Licensure |

| Credential review | Equipment safety | Fire safety inspections | |

| Process | Peer reviews | Review of performance indicators | Infection surveillance |

| Performance evaluations | Flow process analysis | Review of utilization data | |

| Productivity monitors | |||

| Outcome | Practice profiles | Error and complication rate analysis | Mortality rates |

| Rework required | Quality sanctions |

Structure measures

Structure measures indirectly assess care by looking at certain provider characteristics and the physical and organizational resources available to support the delivery of care. Structure measures look at the capability or potential for providing quality care. By their nature, structure measures are static: the organization or individual is evaluated at a unique point in time. The organizational makeup of a facility, operational policies and procedures, technological capabilities, staffing, compliance with safety regulations, and workforce competence are all examples of structures that can be measured.

Process measures

Process measures focus on what is done during the delivery of health care services. Some process measures evaluate the quality of health care professionals’ decisions as they direct a patient’s course of treatment. For instance, are caregivers complying with clinical practice guideline recommendations? Some process measures evaluate staff member compliance with specific procedures or activities. For instance, are hospital admissions staff making input errors when entering patient demographic information into the computer? Health care delivery involves many tasks, both clinical and nonclinical. For this reason, process measures are the most common measurements used to evaluate the quality of health care services.13

Outcome measures

Outcome measures look at the end results of the patient’s encounter with the health care system. A commonly used outcome measure in acute health care settings is patient mortality rates. Although the mortality rate is certainly an important measure, other variables may be necessary to examine adequately the quality of care provided to patients. For instance, what if the patient’s diagnosis is terminal metastatic carcinoma? Would death suggest poor quality care for this patient? Process measures are often necessary to supplement outcome measures to evaluate whether the “right” things are done, such as provision of adequate pain control and provider adherence to living will requirements. Other examples of outcome measures include patient complication and infection rates, patient satisfaction rates, average cost of care, and other results of health services.

Developing performance measures

The choice of performance measures is an important consideration for an HCO because it is impossible to measure all aspects of patient care and services. Several factors must be considered when performance measures are selected. These factors include the following14:

• External accreditation and regulatory requirements

• National quality measurement priorities

• Strategic priorities of the HCO

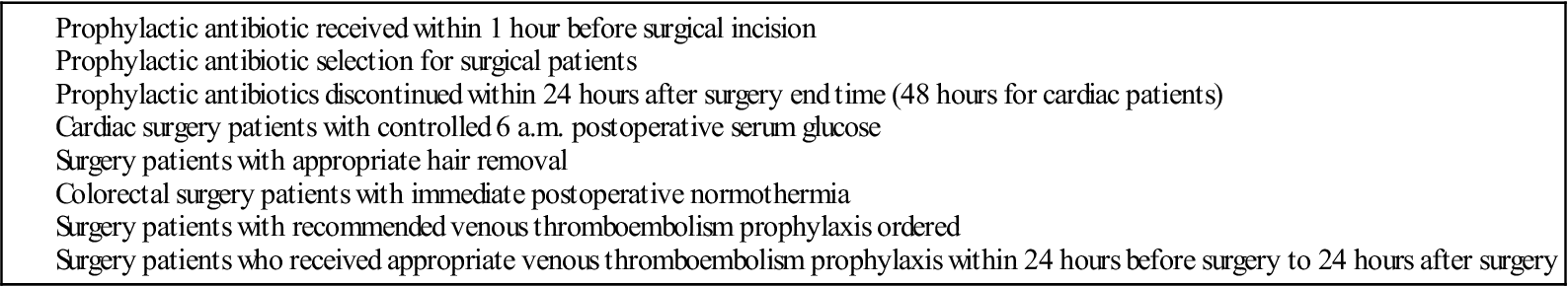

Often HCOs choose to use measures developed by national groups that sponsor performance databases. For instance, CMS has several health care measurement projects involving hospitals, home health agencies, skilled nursing facilities, and other providers. One set of measures is focused on compliance with clinical practice guidelines to prevent postoperative infections. Surgical procedures studied for the CMS surgical care improvement project (SCIP) project include coronary artery bypass graft procedures, cardiac procedures, colon procedures, hip and knee arthroplasty, abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy, and selected vascular surgery procedures. Performance measures for this project, as of 2009, are listed in Table 12-2.15

Table 12-2

SURGICAL CARE IMPROVEMENT PROJECT PERFORMANCE MEASURES

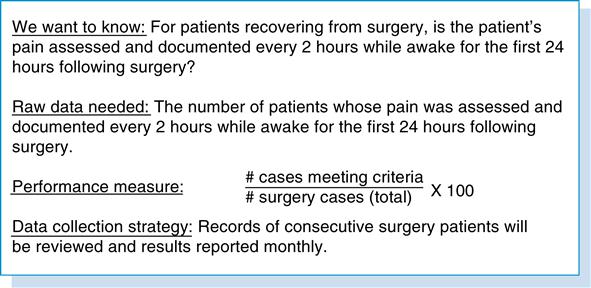

Details about the performance measures in the CMS quality improvement projects and in measurement projects sponsored by other regulatory agencies, accreditation bodies, and professional groups can be found on the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse Web site sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Development of a performance measure involves three basic steps:

These steps are illustrated in Figure 12-1 for a measure of postoperative pain management.

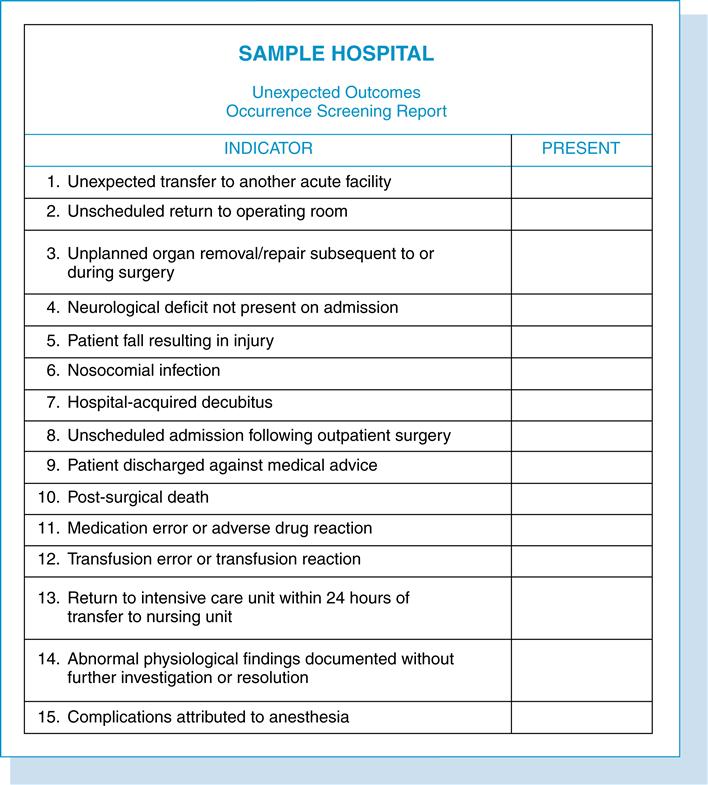

Collecting measurement data

Two types of paper-based forms are commonly used to gather performance measurement data. A checksheet is a form specially designed so that the results can be readily interpreted from the form itself. This form of data collection is ideal for capturing data concurrently (during actual delivery of patient care or services) because the employee can interpret the results and take corrective actions immediately. A data sheet is a form designed to collect data in a simple tabular or column format. Specific bits of data (e.g., numbers, words, or marks) are entered in spaces on the sheet. As a result, additional processing is typically required after the data are collected to construct the performance measure. Illustrated in Figure 12-2 is a data sheet used to capture information about the occurrence of particular events that might take place during a patient’s hospitalization.

One form is completed for each patient record reviewed. Although the example shown is a paper form, the data could be captured in an electronic form or simply entered into a spreadsheet or database application. Those tasked with performing the data collection should understand the data definitions (the exact intended meaning of the variables being collected), have the necessary forms at hand, and be trained in the data collection process such as where in the health record this data item would be located.

With the growth in electronic health records (EHRs), data that were previously gathered manually will likely be available in electronic format. This will reduce, but not totally eliminate, the need for manual data gathering. Even when an HCO has a central data repository for information about patients and their health care experiences, it may be necessary to gather information from other sources. Data warehouse systems provide consolidated and consistent historical data about patient care activities; however, careful planning is necessary to ensure that the information supports performance measurement activities.

Data quality

To achieve their potential value, performance measures must be valid and reliable. Validity refers to the following16:

• Degree to which all items in the measure relate to the performance being measured

• Extent to which all relevant aspects of performance are covered

A reliable measure is stable, showing consistent results over time and among different users of the measure. A reliable measure has low levels of random error. For example, a properly calibrated scale will measure an individual’s weight accurately each time he or she steps on the scale no matter who reads the weight value. A coding skills test would be valid if it accurately distinguishes between high-performing coders and low-performing coders. It would be reliable if the distinction is made each time the test is administered, even if the grader changes.

A vital element of data collection is the need for accuracy. Inaccurate data may give the wrong answer to questions about performance. One of the most troublesome sources of error is called bias. It is important to understand bias and to allow for this during the development and implementation of any data collection system. Well-designed data collection strategies and processes can reduce bias. Some types of biases that may occur include the following:

• Some part of the process or the data has been left out of the data collection process.

• The data collection itself interferes with the process it is measuring.

• The data collector biases (distorts) the data.

• The data collection procedures were not followed or were incorrect or ambiguous.

• Some of the data are missing or were not obtained.

Health information management (HIM) professionals play a vital role in ensuring valid and reliable data collection. From the front-end capture of data to back-end reporting of measurement results, no nonclinical department has greater influence.17 As coordinators of data quality, HIM professionals can influence consistent recording and capture of data that later become worthwhile performance measurement information.

Performance assessment

Performance assessment (sometimes called evaluation, appraisal, or rating) involves a formal periodic review of performance measurement results. If the data collection strategy has been carefully planned, the resulting information should provide a good understanding of performance. After the performance data have been verified for accuracy, it is time for the assessment phase. However, before the results can be analyzed, the information needs to be assembled and presented in a meaningful way. The performance data should help people answer the following questions:

• What is the current performance?

• Should we take any action? What kind of action?

• What contributes the most to undesirable performance (the vital few)?

Reports for analysis

To facilitate performance assessment, data must be presented in a format that makes it easier to draw conclusions. This grouping or summarizing may take several forms: tabulation, graphs, or statistical comparisons. Sometimes a single data grouping will suffice for the purposes of performance assessment. Where larger amounts of data must be dealt with, multiple groupings are essential for creating a clear base for analysis. Spreadsheets and databases are useful for organizing and categorizing performance measurement data to show trends. Performance measurement reports may take many forms. Some of the more common graphical presentations are described in greater detail later in this chapter.

At the assessment stage, the objective is to transfer information to the responsible decision makers. Reports will likely consist of sets of tables or charts of performance measurement results, supplemented with basic conclusions. Before actually presenting any performance information, it is beneficial to evaluate and understand a few key factors:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree