Barbara Lauritsen Christensen

Care of the patient with a gastrointestinal disorder

Objectives

Key terms

achalasia ( k-

k- h-L

h-L -z

-z –

– , p. 189)

, p. 189)

achlorhydria ( -chl

-chl r-H

r-H -dr

-dr –

– , p. 180)

, p. 180)

anastomosis ( -n

-n s-t

s-t -M

-M -s

-s s, p. 189)

s, p. 189)

carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) (k r-s

r-s n-

n- –

– m-br

m-br –

– N-

N- k

k  N-t

N-t -j

-j n, p. 221)

n, p. 221)

dehiscence (d -H

-H S-

S- ntz, p. 200)

ntz, p. 200)

dumping syndrome (D MP-

MP- ng S

ng S N-dr

N-dr m, p. 196)

m, p. 196)

evisceration ( -v

-v s-

s- r-

r- -sh

-sh n, p. 200)

n, p. 200)

exacerbations ( g-z

g-z s-

s- r-B

r-B -sh

-sh nz, p. 205)

nz, p. 205)

hematemesis (h -m

-m -T

-T M-

M- -s

-s s, p. 192)

s, p. 192)

intussusception ( n-t

n-t s-s

s-s s-S

s-S P-sh

P-sh n, p. 182)

n, p. 182)

leukoplakia (l -k

-k -PL

-PL -k

-k –

– , p. 185)

, p. 185)

paralytic (adynamic) ileus (p. 218)

pathognomonic (p th-

th- g-n

g-n -M

-M N-

N- k, p. 183)

k, p. 183)

steatorrhea (st –

– -t

-t -R

-R –

– , p. 210)

, p. 210)

Anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal system

Digestive system

Everyone understands that food is necessary for existence, but not (1) what happens to food once it is chewed and swallowed; (2) how food is prepared for its trip to each individual cell; and (3) the many changes that food undergoes, both chemically and physically. This chapter reviews these changes and their effect on the body.

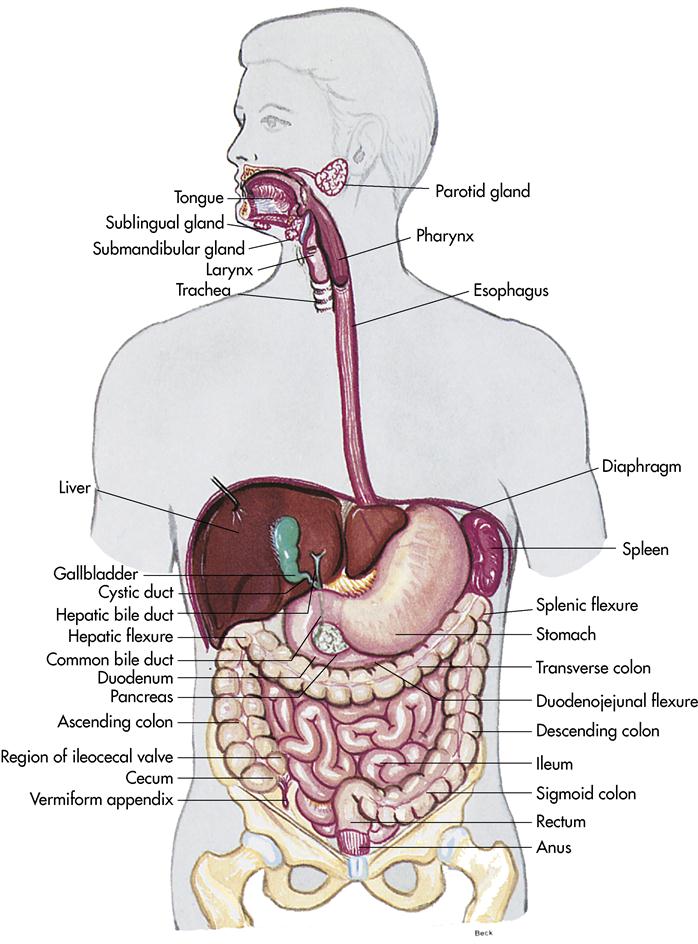

The digestive tract, or alimentary canal, is a musculomembranous tube extending from the mouth to the anus (Figure 5-1). It is approximately 30 feet long. It consists of the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, small intestine, large intestine, and anus. Peristalsis is the coordinated, rhythmic, serial contraction of smooth muscle that forces food through the digestive tract, bile through the bile duct, and urine through the ureter. During peristalsis the tract shortens to approximately 15 feet.

Accessory organs aid in the digestive process but are not considered part of the digestive tract. They release chemicals into the system through a series of ducts. The teeth, tongue, salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas are considered accessory organs.

Organs of the digestive system and their functions

Box 5-1 lists various organs of the digestive system and the accessory organs involved in digestion.

Mouth

The mouth marks the entrance to the digestive system. The floor of the mouth contains a muscular appendage, the tongue. The tongue is involved in chewing, swallowing, and the formation of speech. Tiny elevations, called papillae, contain the taste buds. They differentiate between bitter, sweet, sour, and salty sensations.

Digestion begins in the mouth. Here the teeth mechanically shred and grind the food and the enzymes begin the chemical breakdown of carbohydrates.

Teeth

Each tooth is designed to carry out a specific task. In the center of the mouth are the incisors, which are structured for biting and cutting. Posterior to the incisors are the canines, pointed teeth used for tearing and shredding food. The molars are to the rear of the jaw. These teeth have four cusps (points) and are used for mastication (to crush and grind food).

Salivary glands

The three pairs of salivary glands are the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands (see Figure 5-1). They secrete fluid called saliva, which is approximately 99% water with enzymes and mucus. Normally these glands secrete enough saliva to keep the mucous membranes of the mouth moist. Once food enters the mouth, the secretion increases to lubricate and dissolve the food and to begin the chemical process of digestion. The salivary glands secrete about 1000 to 1500 mL of saliva daily. The major enzyme is salivary amylase (ptyalin), which initiates carbohydrate metabolism. Another enzyme, lysozyme, destroys bacteria and thus protects the mucous membrane from infections and the teeth from decay. After food has been ingested, the salivary glands continue to secrete saliva, which cleanses the mouth.

Esophagus

The esophagus is a muscular, collapsible tube that is approximately 10 inches long, extending from the mouth through the thoracic cavity and the esophageal hiatus to the stomach. Digestion does not take place in the esophagus. Peristalsis moves the bolus (food broken down and mixed with saliva, ready to pass to the stomach) through the esophagus to the stomach in 5 or 6 seconds.

Stomach

The stomach is in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen, directly inferior to the diaphragm (Figure 5-2). A filled stomach is the size of a football and holds approximately 1 L. The stomach entrance is the cardiac sphincter (so named because it is close to the heart); the exit is the pyloric sphincter. As food leaves the esophagus, it enters the stomach through the relaxed cardiac sphincter. The sphincter then contracts, preventing reflux (splashing or return flow), which can be irritating.

Once the bolus has entered the stomach, the muscular layers of the stomach churn and contract to mix and compress the contents with the gastric juices and water. The gastric juices are secretions released by the gastric glands. Digestion of protein begins in the stomach. Hydrochloric acid softens the connective tissue of meats, kills bacteria, and activates pepsin (the chief enzyme of gastric juices that converts proteins into proteoses and peptones). Mucin is released to protect the stomach lining. Intrinsic factor (a substance secreted by the gastric mucosa) is produced to allow absorption of vitamin B12. The stomach breaks the food down into a viscous semiliquid substance called chyme. The chyme passes through the pyloric sphincter into the duodenum for the next phase of digestion.

Small intestine

The small intestine (see Figure 5-1) is a tube that is 20 feet long and 1 inch in diameter. It begins at the pyloric sphincter and ends at the ileocecal valve. It is divided into three major sections: duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. Up to 90% of digestion takes place in the small intestine. The intestinal juices finish the metabolism of carbohydrates and proteins. Bile and pancreatic juices enter the duodenum. Bile from the liver breaks molecules into smaller droplets, which enables the digestive juices to complete their process. Pancreatic juices contain water, protein, inorganic salts, and enzymes. Pancreatic juices are essential in breaking down proteins into their amino acid components, in reducing dietary fats to glycerol and fatty acids, and in converting starch to simple sugars.

The inner surface of the small intestine contains millions of tiny fingerlike projections called villi, which are clustered over the entire mucous surface. The villi are responsible for absorbing the products of digestion into the bloodstream. They increase the absorption area of the small intestine 600 times. Inside each villus is a rich capillary bed, along with modified lymph capillaries called lacteals. Lacteals are responsible for the absorption of metabolized fats.

Large intestine

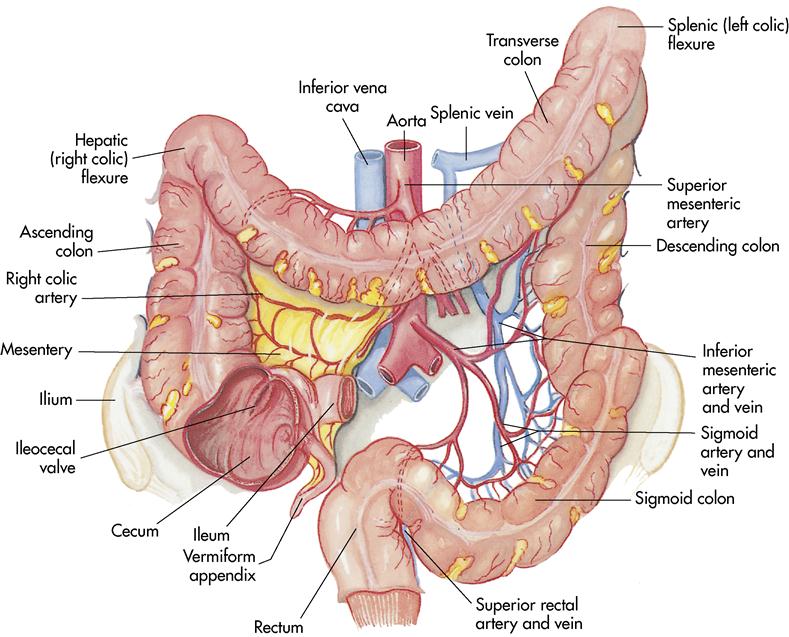

Once the small intestine has finished its specific tasks, the ileocecal valve opens and releases the contents into the large intestine. The large intestine is a tube that is larger in diameter (2 inches) but shorter (5 feet) than the small intestine. It is composed of the cecum; appendix; ascending, hepatic flexure, transverse, splenic flexure, descending, and sigmoid colons; rectum; and anus (Figure 5-3). This is the terminal portion of the digestive tract, which completes the process of digestion. Basically the large intestine has four major functions: (1) completion of absorption of water, (2) manufacture of certain vitamins, (3) formation of feces, and (4) expulsion of feces.

Just inferior to the ileocecal valve is the cecum, a blind pouch approximately 2 to 3 inches long. The vermiform appendix, a small wormlike, tubular structure, dangles from the cecum. To date, no function for the appendix has been discovered. The open end of the cecum connects to the ascending colon, which continues upward on the right side of the abdomen to the inferior area of the liver. The ascending colon then becomes the transverse colon. It crosses to the left side of the abdomen, where it becomes the descending colon. When the descending colon reaches the level of the iliac crest, the sigmoid colon begins and continues toward the midline to the level of the third sacral vertebra.

Bacteria in the large intestine change the chyme into fecal material by releasing the remaining nutrients. The bacteria are also responsible for the synthesis of vitamin K, which is needed for normal blood clotting, and the production of some of the B-complex vitamins. As the fecal material continues its journey, the remaining water and vitamins are absorbed into the bloodstream by osmosis.

Rectum

The rectum is the last 8 inches of the intestine, where fecal material is expelled.

Accessory organs of digestion

Liver

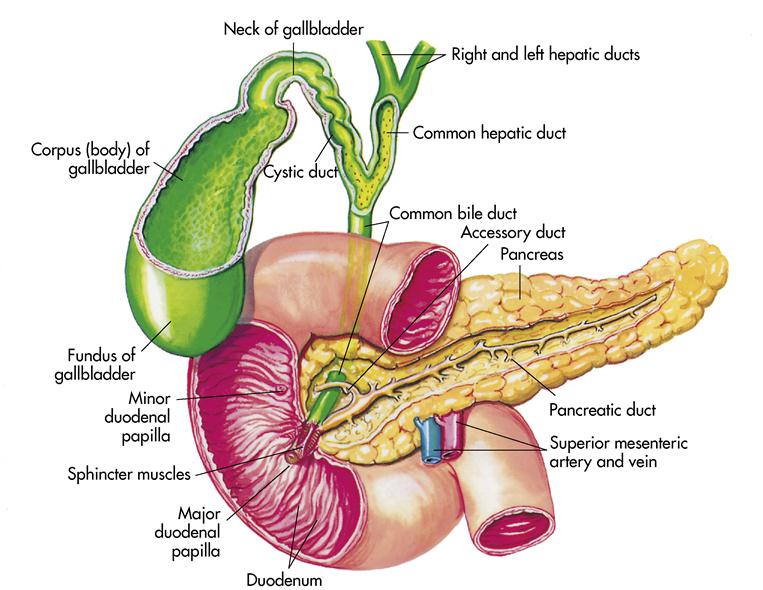

The liver is the largest glandular organ in the body and one of the most complex. In the adult it weighs 3 pounds. It is located just inferior to the diaphragm, covering most of the upper right quadrant and extending into the left epigastrium. It is divided into two lobes. Approximately 1500 mL of blood is delivered to the liver every minute by the portal vein and the hepatic portal artery. The cells of the liver produce a product called bile, a yellow-brown or green-brown liquid. Bile is necessary for the emulsification of fats. The liver releases 500 to 1000 mL of bile per day. Bile travels to the gallbladder through hepatic ducts. The gallbladder is a sac about 3 to 4 inches long located on the right inferior surface of the liver. Bile is stored in the gallbladder until needed for fat digestion (Figure 5-4).

In addition to producing bile, the liver’s functions include managing blood coagulation; manufacturing cholesterol; manufacturing albumin to maintain normal blood volume; filtering out old red blood cells (RBCs) and bacteria; detoxifying poisons (alcohol, nicotine, drugs); converting ammonia to urea; providing the main source of body heat; storing glycogen for later use; activating vitamin D; and breaking down nitrogenous waste (from protein metabolism) to urea, which the kidneys can excrete as waste from the body.

Pancreas

The pancreas is an elongated gland that lies posterior to the stomach (see Figure 5-4). It is involved in both endocrine and exocrine duties. In this chapter, discussion of the pancreas is limited to its exocrine activities.

Each day the pancreas produces 1000 to 1500 mL of pancreatic juice to aid in digestion. This pancreatic juice contains the digestive enzymes protease (trypsin), lipase (steapsin), and amylase (amylopsin). These enzymes are important because they digest the three major components of chyme: proteins, fats, and carbohydrates. The enzymes are transported through an excretory duct to the duodenum. This pancreatic duct connects to the common bile duct from the liver and gallbladder and empties through a small orifice in the duodenum called the major duodenal papilla, or papilla of Vater. In addition, the pancreas contains an alkaline substance, sodium bicarbonate, which neutralizes hydrochloric acid in the gastric juices that enter the small intestine from the stomach.

Regulation of food intake

The hypothalamus, a portion of the brain, contains two centers that have an effect on eating. One center stimulates the individual to eat, and the other signals the individual to stop eating. These centers work in conjunction with the rest of the brain to balance eating habits. However, many other factors also affect eating. For example, distention decreases appetite. Other controls in our bodies, lifestyle, culture, eating habits, emotions, and genetic factors all influence intake of food and individual body build.

Laboratory and diagnostic examinations

Upper gastrointestinal study (upper GI series, UGI)

Rationale

The upper gastrointestinal study (UGI) consists of a series of radiographs of the lower esophagus, stomach, and duodenum using barium sulfate as the contrast medium. A UGI series detects any abnormal conditions of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract, any tumors, or other ulcerative lesions.

Nursing interventions

The patient should take nothing by mouth (NPO) and avoid smoking after midnight the night before the study. Explain the importance of rectally expelling all the barium after the examination. Stools will be light colored until all the barium is expelled (up to 72 hours after the test). Eventual absorption of fecal water may cause a hardened barium impaction. Increasing fluid intake is usually effective. Give the patient milk of magnesia (60 mL) after the examination unless contraindicated.

Tube gastric analysis

Rationale

The stomach contents are aspirated to determine the amount of acid produced by the parietal cells in the stomach. The analysis helps determine the completeness of a vagotomy, confirm hypersecretion or achlorhydria (an abnormal condition characterized by the absence of hydrochloric acid in the gastric juice), estimate acid secretory capacity, or test for intrinsic factor.

Nursing interventions

The patient should receive no anticholinergic medications for 24 hours before the test and should maintain NPO status after midnight to avoid altering the gastric acid secretion. Inform the patient that smoking is prohibited before the test because nicotine stimulates the flow of gastric secretions.

The nurse or radiology personnel inserts a nasogastric (NG) tube into the stomach to aspirate gastric content. Label specimens properly and send them to the laboratory immediately. Remove the NG tube as soon as specimens are collected. The patient may then eat if indicated.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD, UGI endoscopy, gastroscopy)

Rationale

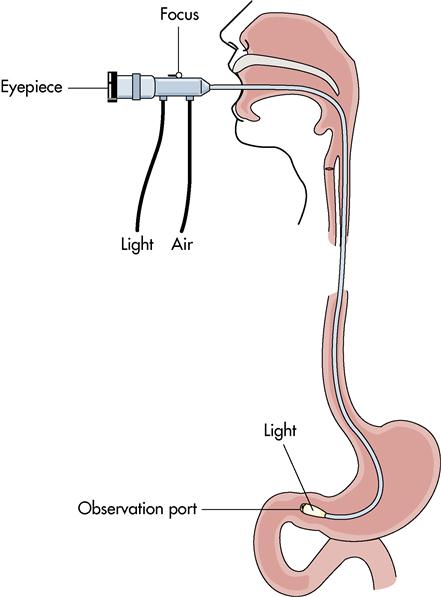

Endoscopy (from endo, within, inward; and scope, to look) enables direct visualization of the upper GI tract by means of a long, fiberoptic flexible scope (Figure 5-5). The esophagus, stomach, and duodenum are examined for tumors, varices, mucosal inflammation, hiatal hernias, polyps, ulcers, Helicobacter pylori, strictures, and obstructions. The endoscopist can also remove polyps, coagulate sources of active GI bleeding, and perform sclerotherapy of esophageal varices. Areas of narrowing can be dilated by the endoscope itself or by passing a dilator through the scope. Camera equipment can be attached to the viewing lens to photograph a pathologic condition. The endoscope can also obtain tissue specimens for biopsy or culture to determine the presence of H. pylori.

Endoscopy enables evaluation of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. A longer fiberoptic scope allows evaluation of the upper small intestine. This is referred to as enteroscopy.

Nursing interventions

Explain the procedure to the patient. The patient should maintain NPO status after midnight. Obtain the patient’s signature on a consent form and complete a preoperative checklist for the endoscopic examination. The patient is usually given a preprocedure intravenous (IV) sedative such as midazolam (Versed). The patient’s pharynx is anesthetized by spraying it with lidocaine hydrochloride (Xylocaine). Therefore do not allow the patient to eat or drink until the gag reflex returns (usually about 2 to 4 hours). Assess for any signs and symptoms of perforation, including abdominal pain and tenderness, guarding, oral bleeding, melena, and hypovolemic shock.

Capsule endoscopy

Rationale

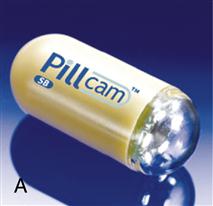

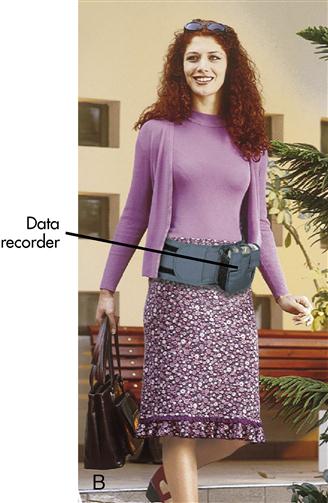

In a capsule endoscopy, the patient swallows a capsule with a camera (approximately the size of a large vitamin) that provides endoscopic evaluation of the GI tract (Figure 5-6). It is commonly used to visualize the small intestine and diagnose diseases (such as Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, and malabsorption syndrome). It also helps identify sources of possible GI bleeding in areas not accessible by upper endoscopy or colonoscopy. The camera takes about 57,000 images during an 8-hour examination. The capsule relays images to a data recorder that the patient wears on a belt. After the examination, images are viewed on a monitor.

Nursing interventions

Dietary preparation is similar to that for colonoscopy. The patient swallows the video capsule and is usually kept NPO until 4 to 6 hours later. The procedure is comfortable for most patients. Eight hours after swallowing the capsule, the patient returns to have the monitoring device removed. Peristalsis causes passage of the disposable capsule with a bowel movement.

Barium swallow and gastrografin studies

Rationale

This barium contrast study is a more thorough study of the esophagus than that provided by most UGI examinations. As in most barium contrast studies, defects in luminal filling and narrowing of the barium column indicate tumor, scarred stricture, or esophageal varices. The barium swallow allows easy recognition of anatomical abnormalities, such as hiatal hernia. Left atrial dilation, aortic aneurysm, and paraesophageal tumors (such as bronchial or mediastinal tumors) may cause extrinsic compression of the barium column within the esophagus.

Diatrizoate meglumine and diatrizoate sodium (Gastrografin) is a product now used in place of barium for patients who are susceptible to bleeding from the GI system and who are being considered for surgery. Gastrografin is water soluble and rapidly absorbed, so it is preferable when a perforation is suspected. Gastrografin facilitates imaging through radiographs, but if the product escapes from the GI tract, it is absorbed by the surrounding tissue. In contrast, if barium leaks from the GI tract, it is not absorbed and can lead to complications.

Nursing interventions

The patient should maintain NPO status after midnight. Food and fluid in the stomach prevent the barium from accurately outlining the GI tract, and the radiographic results may be misleading. Explain the importance of rectally expelling all barium. Stools will be light colored until this occurs. Eventual absorption of fecal water may cause a hardened barium impaction. Increasing fluid intake is usually effective. Give milk of magnesia (60 mL) after the barium swallow examination unless contraindicated.

Esophageal function studies (bernstein test)

Rationale

The Bernstein test, an acid-perfusion test, is an attempt to reproduce the symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. It helps differentiate esophageal pain caused by esophageal reflux from that caused by angina pectoris. If the patient suffers pain with the instillation of hydrochloric acid into the esophagus, the test is positive and indicates reflux esophagitis.

Nursing interventions

Avoid sedating the patient, since the patient’s participation is essential for swallowing the tubes, swallowing during acid clearance, and describing any discomfort during the instillation of hydrochloric acid. The patient is NPO for 8 hours before the examination. Withhold any medications that may interfere with the production of acid, such as antacids and analgesics.

Examination of stool for occult blood

Rationale

Tumors of the large intestine grow into the lumen (the cavity or channel within a tube or tubular organ) and are subject to repeated trauma by the fecal stream. Eventually the tumor ulcerates and bleeding occurs. Usually the bleeding is so slight that gross blood is not seen in the stool. If this occult blood (blood that is obscure or hidden from view) is detected in the stool, suspect a benign or malignant GI tumor. Tests for occult blood are also called guaiac, Hemoccult, and Hematest.

Occult blood in the stool may occur also in ulceration and inflammation of the upper or lower GI system. Other causes include swallowing blood of oral or nasopharyngeal origin.

Stool may be obtained by digital retrieval by the nurse or physician. However, the patient is usually asked to collect stool in an appropriate container. Obtain a specimen for occult blood before barium studies are done.

Nursing interventions

Instruct the patient to keep the stool specimen free of urine or toilet paper, since either can alter the test results. The nurse or patient should don gloves and use tongue blades to transfer the stool to the proper receptacle. The patient should keep the diet free of organ meat for 24 to 48 hours before a guaiac test.

Sigmoidoscopy (lower GI endoscopy)

Rationale

Endoscopy of the lower GI tract allows visualization and, if indicated, access to obtain biopsy specimens of tumors, polyps, or ulcerations of the anus, rectum, and sigmoid colon. The lower GI tract is difficult to visualize radiographically, but sigmoidoscopy allows direct visualization. Microscopic review of tissue specimens obtained using this procedure lead to diagnoses of many lower bowel disorders.

Nursing interventions

Explain the procedure to the patient and have him or her sign a consent form. Administer enemas as ordered on the evening before or the morning of the examination to ensure optimum visualization of the lower GI tract. After the examination, observe the patient for evidence of bowel perforation (abdominal pain, tenderness, distention, and bleeding).

Barium enema study (lower GI series)

Rationale

The barium enema (BE) study consists of a series of radiographs of the colon used to demonstrate the presence and location of polyps, tumors, and diverticula. It can also detect positional abnormalities (such as malrotation). Barium sulfate assists in visualization of mucosal detail. Therapeutically, the BE study may be used to reduce nonstrangulated ileocolic intussusception (infolding of one segment of the intestine into the lumen of another segment) in children.

Nursing interventions

The evening before the BE, administer cathartics such as magnesium citrate or other cathartics designated by institution policy. Also administer a cleansing enema the evening before or the morning of the BE if directed by physician’s order or hospital policy. Milk of magnesia (60 mL) may be ordered after the BE to stimulate evacuation of the barium.

After the BE study, assess the patient for complete evacuation of the barium. Retained barium may cause a hardened impaction. Stool will be light colored until all the barium has been expelled.

Colonoscopy

Rationale

The development of the fiberoptic colonoscope has enabled examination of the entire colon—from anus to cecum—in a high percentage of patients. Colonoscopy can detect lesions in the proximal colon, which would not be found by sigmoidoscopy. Benign and malignant neoplasms, mucosal inflammation or ulceration, and sites of active hemorrhage can also be visualized. Biopsy specimens can be obtained and small tumors removed through the scope with the use of cable-activated instruments. Actively bleeding vessels can be coagulated.

A less invasive test than a standard colonoscopy is called virtual colonoscopy. This test uses CT scanning or MRI with computer software to produce images of the colon and rectum. The colon preparation is similar to that for a regular colonoscopic examination. Sedatives are not required and no scope is needed (Lewis et al., 2007).

Patients who have had cancer of the colon are at high risk for developing a subsequent colon cancer; patients who have a family history of colon cancer are also at high risk. For these patients, colonoscopy allows early detection of any primary or secondary tumors.

Nursing interventions

Explain the procedure to the patient and have him or her sign a consent form. Instruct the patient regarding dietary restrictions: Usually a clear liquid diet is permitted 1 to 3 days before the procedure to decrease the residue in the bowel, and then NPO status is maintained for 8 hours before the procedure. Administer a cathartic, enemas, and premedication as ordered to decrease the residue in the bowel. GoLYTELY, an oral or NG colonic lavage, is an osmotic electrolyte solution that is now commonly used as a cathartic (Box 5-2). It is a polyethylene glycol solution. If it is taken orally, instruct the patient to drink the solution rapidly: 8 ounces (240 mL) every 15 minutes until enough solution has been consumed to make the colonic contents a light yellow liquid. Powdered lemonade may be added to make the oral solution more palatable. If it is given per lavage, it must be given rapidly. Taking the solution slowly will not clean the colon efficiently. Provide warm blankets during the procedure, since many patients experience hypothermia while taking GoLYTELY. Provide a commode at the bedside for older adults and frail patients. Check the patient’s stool after the prep to make certain it is light yellow and liquid. A preprocedure IV sedative such as midazolam is often given.

After the colonoscopy, check for evidence of bowel perforation (abdominal pain, guarding, distention, tenderness, excessive rectal bleeding, or blood clots) and examine stools for gross blood. Assess for hypovolemic shock.

Stool culture

Rationale

The feces (stool) can be examined for the presence of bacteria, ova, and parasites (a plant or animal that lives on or within another living organism and obtains some advantage at its host’s expense). The physician may order a stool for culture of bacteria or of ova and parasites (O&P). Many bacteria (such as Escherichia coli) are indigenous in the bowel. Bacterial cultures are usually done to detect enteropathogens (such as Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella or Shigella organisms, E. coli O157:H7, or Clostridium difficile).

When a patient is suspected of having a parasitic infection, the stool is examined for O&P. Usually at least three stool specimens are collected on subsequent days. Because culture results are not available for several days, they do not influence initial treatment, but they do guide subsequent treatment if bacterial infection is present.

Nursing interventions

If an enema must be administered to collect specimens, use only normal saline or tap water. Soapsuds or any other substance could affect the viability of the organisms collected.

Stool samples for O&P are obtained before barium examinations. Instruct the patient not to mix urine with feces. Don gloves to collect the specimen, and ensure the specimen is taken to the laboratory within 30 minutes of collection in specified container.

Obstruction series (flat plate of the abdomen)

Rationale

The obstruction series is a group of radiographic studies performed on the abdomen of patients who have suspected bowel obstruction, paralytic ileus, perforated viscus (any large interior organ in any of the great body cavities), or abdominal abscess. The series usually consists of at least two radiographic studies. The first is an erect abdominal radiographic study that allows visualization of the diaphragm. Radiographs are examined for evidence of free air under the diaphragm, which is pathognomonic (signs or symptoms specific to a disease condition) of a perforated viscus. This radiographic study is used also to detect air-fluid levels within the intestine.

Nursing interventions

For adequate visualization, ensure that this study is scheduled before any barium studies.

Disorders of the mouth

Common disorders of the mouth and esophagus that interfere with adequate nutrition include poor dental hygiene, infections, inflammation, and cancer.

Dental plaque and caries

Etiology and pathophysiology

Dental decay is an erosive process that results from the action of bacteria on carbohydrates in the mouth, which in turn produce acids that dissolve tooth enamel. Most Americans (95%) experience tooth decay at some time in their life. Dental decay can be caused by several factors:

Medical management

Dental caries is treated by removal of affected areas of the tooth and replacement with some form of dental material. Treatment of periodontal disease centers on removal of plaque from the teeth. If the disease is advanced, surgical interventions on the gingivae and alveolar bone may be necessary.

Nursing interventions and patient teaching

Proper technique for brushing and flossing the teeth at least twice a day is the primary focus for teaching these patients. Plaque forms continuously and must be removed periodically through regular visits to the dentist. Stress the importance of prevention through continual care. Because carbohydrates create an environment in which caries develop and plaque accumulates more easily, include proper nutrition in patient teaching. When the patient is ill, the mouth’s normal cleansing action is impaired. Illnesses, drugs, and irradiation all interfere with the normal action of saliva. If the patient is unable to manage oral hygiene, the nurse must assume this responsibility.

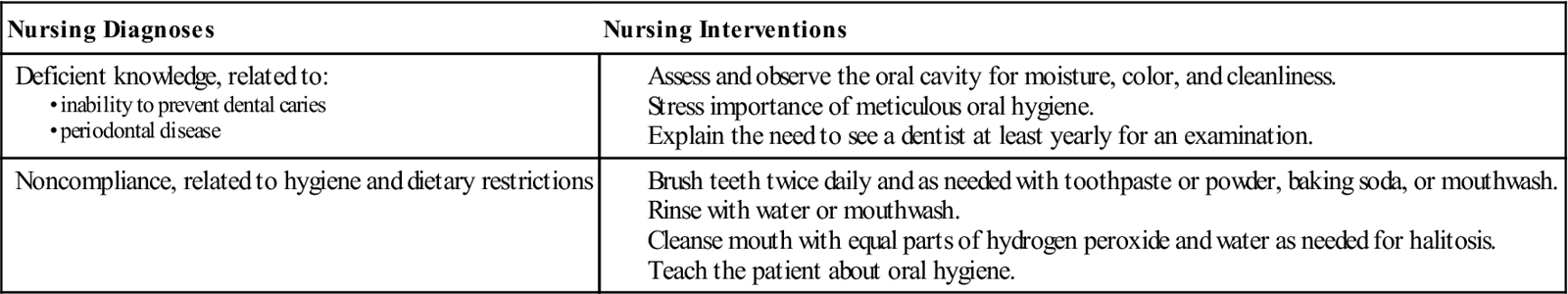

Nursing diagnoses and interventions for the patient with dental plaque and caries include but are not limited to the following:

Prognosis

The prevention and elimination of dental plaque and caries are directly related to oral hygiene, dental care, nutrition, and heredity. All but heredity are controllable factors. The prognosis is more favorable for people who brush, floss, regularly visit the dentist for removal of affected areas, eat low-carbohydrate foods, and drink fluoridated water.

Candidiasis

Etiology and pathophysiology

Candidiasis is any infection caused by a species of Candida, usually C. albicans. Candida is a fungal organism normally present in the mucous membranes of the mouth, intestinal tract, and vagina; it is also found on the skin of healthy people. This infection is also referred to as thrush or moniliasis.

This disease appears more commonly in the newborn infant, who becomes infected while passing through the birth canal. In the older individual, candidiasis may be found in patients with leukemia, diabetes mellitus, or alcoholism, and in patients who are taking antibiotics (chlortetracycline or tetracycline), are undergoing corticosteroid inhalant treatment, or are immunosuppressed (e.g., patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS] or those receiving chemotherapy or radiation therapy).

Clinical manifestations

Candidiasis appears as pearly, bluish white “milk-curd” membranous lesions on the mucous membranes of the mouth, tongue, and larynx. One or more lesions may be on the mucosa, depending on the duration of the infection. If the patch or plaque is removed, painful bleeding can occur.

Medical management

Nystatin or amphotericin B (an oral suspension) or buccal tablets or fluconazole (Diflucan), half-strength hydrogen peroxide and saline mouth rinses may provide some relief.

Nursing interventions

Use meticulous hand hygiene to prevent spread of infection. The infection may be spread in the nursery by carelessness of nursing personnel. Hand hygiene, care of feeding equipment, and cleanliness of the mother’s nipples are important to prevent spread. Cleanse the infant’s mouth of any foreign material, rinsing the mouth and lubricating the lips. Inspect the mouth using a flashlight and tongue blade.

For adults, instruct the patient to use a soft-bristled toothbrush and administer a topical anesthetic (lidocaine or benzocaine) to the mouth 1 hour before meals. Give soft or pureed foods and avoid hot, cold, spicy, fried, or citrus foods.

Prognosis

If the host has a strong defense system and medical treatment is initiated early in the course of the disease, the prognosis is good.

Carcinoma of the oral cavity

Etiology and pathophysiology

Oral (or oropharyngeal) cancer may occur on the lips, the oral cavity, the tongue, and the pharynx. The tonsils are occasionally involved. Most of these tumors are squamous cell epitheliomas that grow rapidly and metastasize to adjacent structures more quickly than do most malignant tumors of the skin. In the United States, oral cancer accounts for 4% of the cancers in men and 2% in women. An estimated 35,310 new cases and 7590 deaths from oral cavity and pharynx cancer were expected in 2008. Death rates have been decreasing since the 1970s, with rates declining faster in the 2000s (American Cancer Society [ACS], Cancer facts and figures, 2008).

Tumors of the salivary glands occur primarily in the parotid gland and are usually benign. Tumors of the submaxillary gland have a high incidence of malignancy. These malignant tumors grow rapidly and may be accompanied by pain and impaired facial function.

Kaposi’s sarcoma is a malignant skin tumor that occurs primarily on the legs of men between 50 and 70 years of age. It is seen with increased frequency as a nonsquamous tumor of the oral cavity in patients with AIDS. The lesions are purple and nonulcerated. Irradiation is the treatment of choice.

The tumor seen with cancer of the lip is usually an epithelioma. It occurs most frequently as a chronic ulcer of the lower lip in men. The cure rate for cancer of the lip is high because the lesion is apparent to the patient and to others. Metastasis to regional lymph nodes has occurred in only 10% of people when diagnosed. In some instances a lesion may spread rapidly and involve the mandible and the floor of the mouth by direct extension. Occasionally the tumor may be a basal cell lesion that starts in the skin and spreads to the lip.

Cancer of the anterior tongue and floor of the mouth may seem to occur together because their spread to adjacent tissues is so rapid. Because of the tongue’s abundant vascular and lymphatic drainage, metastasis to the neck has already occurred in more than 60% of patients when the diagnosis is made. There is a higher incidence of cancers of the mouth and throat among people who are heavy drinkers and have a history of tobacco use (e.g., cigar, cigarette, pipe, chewing tobacco). Also, data show that the mortality rate for males between the ages of 10 and 20 has doubled over the past 30 years as a result of the use of smokeless tobacco (snuff). The combination of high alcohol consumption and smoking or chewing tobacco causes an apparent breakdown in the body’s defense mechanism. Predisposing factors include exposure to the sun and wind.

Clinical manifestations

Leukoplakia (a white, firmly attached patch on the mouth or tongue mucosa) may appear on the lips and buccal mucosa. These nonsloughing lesions cannot be rubbed off by simple mechanical force. They can be benign or malignant. A small percentage develop into squamous cell carcinomas, and biopsy is recommended if the lesions persist for longer than 2 weeks. They occur most frequently between the ages of 50 and 70 years and appear more commonly in men.

Assessment

Collection of subjective data includes understanding that malignant lesions of the mouth are usually asymptomatic. The patient may feel only a roughened area with the tongue. As the disease progresses, the first complaints may be (1) difficulty chewing, swallowing, or speaking; (2) edema, numbness, or loss of feeling in any part of the mouth; and (3) earache, facial pain, and toothache, which may become constant. Cancer of the lip is associated with discomfort and irritation caused by a nonhealing lesion, which may be raised or ulcerated. Malignancy at the base of the tongue produces less obvious symptoms: slight dysphagia, sore throat, and salivation.

Collection of objective data includes observing for premalignant lesions, including leukoplakia. Unusual bleeding in the mouth, some blood-tinged sputum, lumps or edema in the neck, and hoarseness may be observed.

Diagnostic tests

Indirect laryngoscopy is an important diagnostic test for examination of the soft tissue. This procedure is especially important for men 40 years of age or older who have dysphagia and a history of smoking and alcohol ingestion. Radiographic evaluation of the mandibular structures is another essential part of the head and neck examination to rule out cancer. Excisional biopsy is the most accurate method for making a definitive diagnosis. Oral exfoliative cytology is used for screening intraoral lesions. A scraping of the lesion provides cells for cytologic examination. The chance for a false-negative finding is about 26%.

Medical management

Treatment depends on the location and staging of the malignant tumor. Stage I oral cancers are treated by surgery or radiation. Stages II and III cancers require both surgery and radiation. Chemotherapy may also be used when surgery and radiation therapy fail or as the initial therapy for smaller tumors. Treatment for stage IV cancer is usually palliative. The survival rate for patients with oral cancers averages less than 50%.

Small, accessible tumors can be excised surgically. Surgical options include a glossectomy, removal of the tongue; hemiglossectomy, removal of part of the tongue; mandibulectomy, removal of the mandible; and total or supraglottic laryngectomy, removal of the entire larynx or the portion above the true vocal cords.

Large tumors usually require more extensive and traumatic surgery. In a functional neck dissection of neck cancer with no growth in the lymph nodes, the surgeon removes the lymph nodes but preserves the jugular vein, the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and the spinal accessory nerve. In radical neck dissection, all these structures are removed and reconstructive surgery is necessary after tissue resection. Patients may have drains in the incision sites that are connected to suction to aid healing and reduce hematomas. A tracheostomy may also be performed, depending on the degree of tumor invasion.

Because of the location of the surgery, complications can occur. These include airway obstruction, hemorrhage, tracheal aspiration, facial edema, fistula formation, and necrosis of the skin flaps. If the patient has difficulty swallowing, a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube may be inserted to allow for adequate nutritional intake. Neurologic complications can occur because of nerves being severed and manipulated during surgery.

Radiation therapy may involve (1) external radiation by roentgenograms or other radioactive substances or (2) internal radiation by means of needles or seeds. The purpose of radiation therapy is to shrink the tumor. It can be given preoperatively or postoperatively, depending on the physician’s preference and the patient’s disease process. In more advanced cases, chemotherapy may be combined with radiation postoperatively to make the patient more comfortable. Other treatment options include laser excision.

Nursing interventions and patient teaching

A holistic approach to patient care includes awareness of the patient’s level of knowledge regarding the disease, emotional response and coping abilities, and spiritual needs. Nursing interventions must be individualized to the patient—beginning with the preoperative stage, continuing through the postoperative stage, and ending after the patient’s rehabilitation in the home environment. Family members, hospice workers, close friends, social workers, and pastoral care staff may provide information and support during this potentially fatal disease.

Nursing diagnoses and interventions for the patient with oral cancer include but are not limited to the following:

| Nursing Diagnoses | Nursing Interventions |

Imbalanced nutrition, less than body requirements, related to:Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

-K

-K K-s

K-s –

– ,

,  s-F

s-F -j

-j –

– ,

,  -m

-m n,

n,  L-

L- h-n

h-n ,

,  -K

-K LT,

LT,  -M

-M SH-

SH- n,

n,  -m

-m ,

,  -N

-N Z-m

Z-m s,

s,  L-v

L-v -l

-l s,

s,