Barbara Lauritsen Christensen

Care of the patient with a reproductive disorder

Objectives

1. List and describe the functions of the organs of the male and female reproductive tracts.

2. Discuss menstruation and the hormones necessary for a complete menstrual cycle.

3. Discuss the impact of illness on the patient’s sexuality.

6. List nursing interventions for patients with menstrual disturbances.

9. List four nursing diagnoses pertinent to the patient with endometriosis.

10. Identify the clinical manifestations of a vaginal fistula.

13. Identify four nursing diagnoses pertinent to ovarian cancer.

15. Describe six important points to emphasize in teaching breast self-examination.

16. Compare four surgical approaches for cancer of the breast.

17. Discuss adjuvant therapies for breast cancer.

18. Discuss nursing interventions for the patient who has had a modified radical mastectomy.

21. Distinguish between hydrocele and varicocele.

22. Discuss the importance of monthly testicular self-examination beginning at 15 years of age.

23. Discuss patient education related to prevention of sexually transmitted infections.

Key terms

candidiasis (k n-d

n-d -D

-D –

– -s

-s s, p. 591)

s, p. 591)

carcinoma in situ (k r-s

r-s -N

-N -m

-m

n S

n S -t

-t , p. 565)

, p. 565)

Chlamydia trachomatis (kl -M

-M D-

D- –

– tr

tr -K

-K -m

-m -t

-t s, p. 591)

s, p. 591)

circumcision (s r-k

r-k m-S

m-S ZH-

ZH- n, p. 584)

n, p. 584)

climacteric (kl -M

-M K-t

K-t r-

r- k, p. 551)

k, p. 551)

colporrhaphy (k l-P

l-P R-

R- -f

-f , p. 562)

, p. 562)

colposcopy (k l-P

l-P S-k

S-k -p

-p , p. 542)

, p. 542)

cryptorchidism (kr p-T

p-T R-k

R-k -d

-d z-

z- m, p. 585)

m, p. 585)

culdoscopy (k l-D

l-D S-k

S-k -p

-p , p. 542)

, p. 542)

curettage (K -r

-r -t

-t hzh, p. 544)

hzh, p. 544)

dysmenorrhea (d s-m

s-m n-

n- -R

-R –

– , p. 546)

, p. 546)

endometriosis ( n-d

n-d -m

-m -tr

-tr –

– -s

-s s, p. 560)

s, p. 560)

epididymitis ( p-

p- -d

-d d-

d- -M

-M -t

-t s, p. 584)

s, p. 584)

introitus ( n-TR

n-TR –

– -t

-t s, p. 562)

s, p. 562)

laparoscopy (l -p

-p -R

-R S-k

S-k -p

-p , p. 542)

, p. 542)

mammography (m m-M

m-M G-r

G-r -f

-f , p. 544)

, p. 544)

metrorrhagia (m -tr

-tr -R

-R -j

-j , p. 546)

, p. 546)

panhysterosalpingo-oophorectomy (p n-H

n-H S-t

S-t r-

r- -S

-S L-p

L-p ng-g

ng-g -oof-

-oof- -R

-R K-t

K-t -m

-m , p. 569)

, p. 569)

Papanicolaou (Pap) test (smear) (p -p

-p -N

-N -k

-k -l

-l u t

u t st, sm

st, sm r, p. 542)

r, p. 542)

procidentia (pr -s

-s -D

-D N-sh

N-sh , p. 562)

, p. 562)

sentinel lymph node mapping (S N-t

N-t -n

-n l l

l l mf n

mf n d M

d M P-

P- ng, p. 574)

ng, p. 574)

trichomoniasis (tr k-

k- -m

-m -N

-N –

– -s

-s s, p. 590)

s, p. 590)

Conception and birth are made possible through the dynamics of the normally functioning male and female reproductive systems. Reproduction of like individuals is necessary for the continuation of the species. The male and female sex glands (gonads) produce the gametes (sperm, ova) that unite to form a fertilized egg (zygote), the beginning of a new life.

Anatomy and physiology of the reproductive system

Male reproductive system

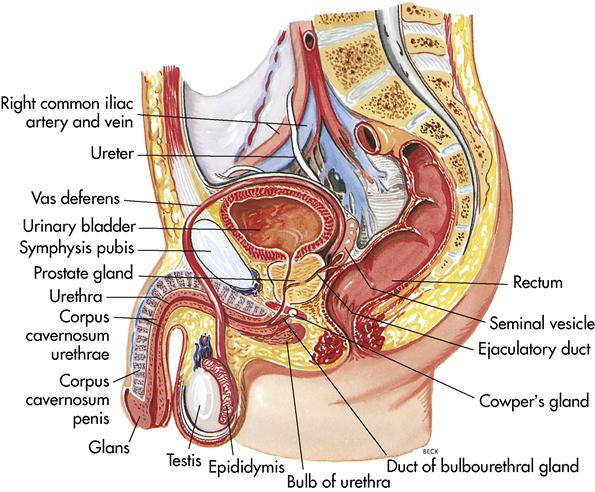

The organs of the male reproductive system include the testes, the ductal system, the accessory glands, and the penis (Figure 12-1). These structures have various functions: (1) producing and storing sperm, (2) depositing sperm for fertilization, and (3) developing the male secondary sex characteristics.

Testes (testicles)

The two oval testes (gonads) are enclosed in the scrotum, a saclike structure that lies suspended from the exterior abdominal wall. This position keeps the temperature in the testes below normal body temperature, which is necessary for viable sperm production and storage. Each testis contains one to three coiled seminiferous tubules that produce the sperm cells. After puberty, millions of sperm cells are produced daily. The testes also produce the hormone testosterone. Testosterone is responsible for the development of male secondary sex characteristics.

Ductal system

Epididymis

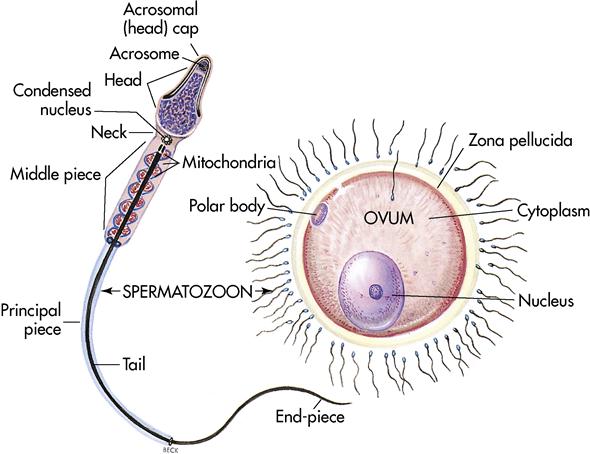

Sperm (Figure 12-2) produced in the seminiferous tubules immediately travel through a network of ducts called the rete testis. These passageways contain cilia that sweep sperm out of the testes into the epididymis, a tightly coiled tube structure that lies superior to the testes and extends posteriorly. With sexual stimulation smooth muscle within the walls of the epididymis contract, forcing the sperm along the seminiferous tubules of the testes to the vas deferens.

Ductus deferens (vas deferens)

The ductus deferens is approximately 18 inches (46 cm) long and rises along the posterior wall of the testes. As it moves upward, it passes through the inguinal canal into the pelvic cavity and loops over the urinary bladder. The ductus deferens, the nerves, and the blood vessels are enclosed in a connective tissue sheath called the spermatic cord. If a man chooses to be sterilized for birth control, it is a simple procedure to make small slits on either side of the scrotum and sever the ductus deferens. This procedure is called a vasectomy. It renders the man sterile because sperm can no longer be expelled.

Ejaculatory duct and urethra

Behind the urinary bladder, the ejaculatory duct connects with the ductus deferens. The ejaculatory duct is only 1 inch (2.5 cm) long. It unites with the urethra to pass through the prostate gland. Each of the two ejaculatory ducts empties into the prostate urethra. The urethra extends the length of the penis with the urinary meatus. The urethra carries both sperm and urine, but, because of the urethral sphincter, it does not do so at the same time.

Accessory glands

The ductal system transports and stores sperm. The accessory glands, which produce seminal fluid (semen), include the seminal vesicles, the prostate gland, and Cowper’s glands. With each ejaculation (2 to 5 mL of fluid), approximately 200 to 500 million sperm are released.

Seminal vesicles

The seminal vesicles are paired structures that lie at the base of the bladder and produce 60% of the volume of semen. The fluid is released into the ejaculatory ducts to meet with the sperm.

Prostate gland

The single, doughnut-shaped prostate gland surrounds the neck of the bladder and urethra. It is a firm structure, about the size of a chestnut, composed of muscular and glandular tissue. The prostate secretes alkaline fluid that contributes to motility of sperm. Smooth muscle of the prostate contracts during ejaculation, expelling semen from the urethra. The ejaculatory duct passes obliquely through the posterior part of the gland. The prostate gland often hypertrophies with age, expanding to surround the urethra and making voiding difficult.

Cowper’s glands

Cowper’s glands are two pea-sized glands under the male urethra. They correspond to the Bartholin’s glands in women and provide lubrication during sexual intercourse.

Urethra and penis

The male urethra has two purposes: conveying urine from the bladder and carrying sperm to the outside. The cylindrical penis is the organ of copulation. The shaft of the penis ends with an enlarged tip called the glans penis. The skin covering the penis, called the prepuce, or foreskin, lies in folds around the glans. This excess tissue is sometimes removed in a surgical procedure called circumcision to prevent phimosis (tightness of the prepuce of the penis that prevents retraction of the foreskin over the glans).

Three masses of erectile tissue, the corpus spongiosum and two copora cavernosa, contain numerous sinuses that fill the shaft of the penis. With sexual stimulation the sinuses fill with blood, causing the penis to become erect. Sexual stimulation concludes with ejaculation, which is brought about by peristalsis of the reproductive ducts and contraction of the prostate gland. After ejaculation, the penis returns to a flaccid state.

Sperm

Spermatogenesis (the process of developing spermatozoa) begins at puberty and continues throughout life. Mature sperm consist of three distinct parts: (1) the head; (2) the midpiece; and (3) the tail, which propels the sperm. Once deposited in the female reproductive system, mature sperm live approximately 48 hours (or in some cases up to 5 days). If they come in contact with a mature egg, the enzyme on the head of each sperm bombards the egg in an attempt to break down its coating (see Figure 12-2). It takes thousands of sperm to break the coating, but only one sperm enters and fertilizes the egg. The remaining sperm disintegrate. Once fertilization takes place, a chemical change occurs making the ova impenetrable for other sperm.

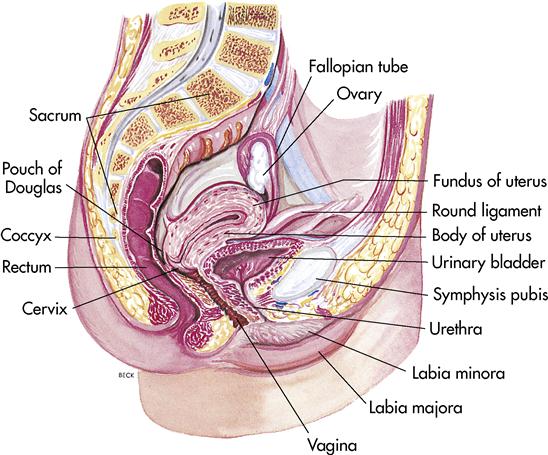

Female reproductive system

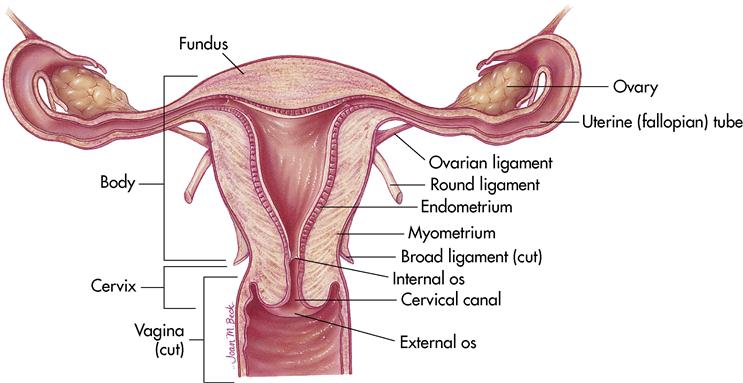

The organs of the female reproductive system include the ovaries, the uterus, the fallopian tubes, and the vagina (Figure 12-3). These organs, along with a few accessory structures, produce the ovum, house the fertilized egg, maintain the embryo, and nurture the newborn infant. The ability to conceive and nurture this new human being requires the intricate balance of many hormones and the menstrual cycle.

Ovaries

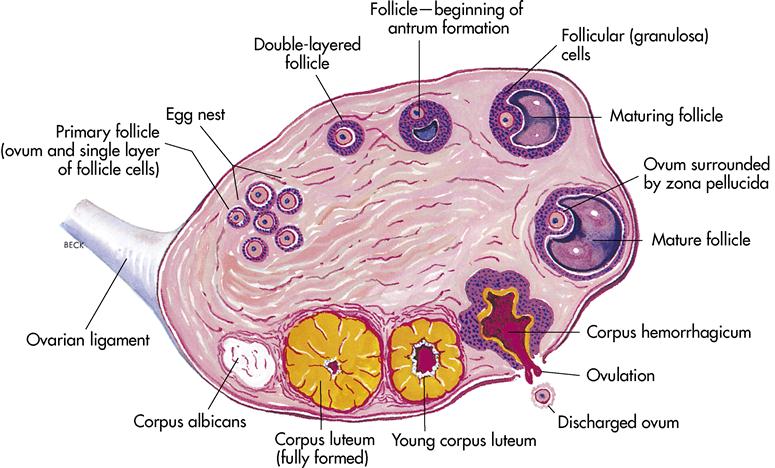

The paired ovaries (gonads) are the size and shape of almonds. They are located bilateral to the uterus immediately inferior to the fallopian fimbriae. At puberty they release progesterone and the female sex hormone estrogen, and they release a mature egg during the menstrual cycle. Each ovary contains 30,000 to 40,000 microscopic ovarian follicles.

Fallopian tubes (oviducts)

The fallopian tubes are a pair of ducts opening at one end into the fundus (upper portion of the uterus) and at the other end into the peritoneal cavity, over the ovary. They are approximately 4 inches (10 cm) long with the fimbriae at the distal ends. The entire inner surface of the tubes is lined with cilia. When the graafian follicle of the ovary ruptures and releases the mature ovum, the fimbriae sweep the ovum into the fallopian tube. Fertilization takes place in the outer third of this tube, and the fertilized ovum (zygote) is moved through the tube by a combination of muscular peristaltic movements and the sweeping action of the cilia. If the mature ovum is not fertilized, it disintegrates.

Uterus

The uterus is shaped like an inverted pear and measures 3 × 2 × 1 inches (7.5 × 5 × 2.5 cm) in the nonpregnant state (Figure 12-4). It is located between the urinary bladder and the rectum and consists of three layers of tissue: (1) endometrium, the inner layer; (2) myometrium, the middle layer; and (3) perimetrium, the outer layer. The uterus is divided into three major portions (see Figure 12-4). The fundus (upper, rounded portion) is the insertion site of the fallopian tubes. The larger midsection is the corpus (body). The smaller, narrower lower portion of the uterus is the cervix, part of which actually descends into the vaginal vault. During pregnancy the uterus is capable of enlarging up to 500 times.

Vagina

The vagina is a thin-walled, muscular, tubelike structure of the female genitalia, approximately 3 inches (7.5 cm) long. It is located between the urinary bladder and the rectum. The superior portion articulates with the cervix of the uterus; the inferior portion opens to the outside of the body. The vagina is lined with mucous membrane, responsible for lubrication during sexual activity. The walls of the vagina normally lie in folds called rugae. This enables the vagina to stretch to receive the penis during intercourse and to allow passage of the infant during birth.

The external opening of the vagina is covered by a fold of mucous membrane, skin, and fibrous tissue called the hymen. For centuries the hymen was a symbol of virginity, but it is now known that rigorous exercise or the insertion of a tampon may tear the hymen. If the hymen does remain intact, it is ruptured by coitus (intercourse).

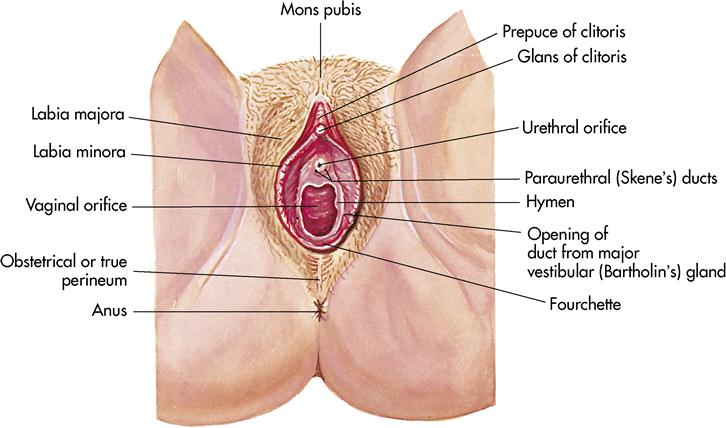

External genitalia

The reproductive structures located outside the body are the external genitalia, or vulva. These structures include the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, and vestibule (Figure 12-5).

Located superior to the symphysis pubis is a mound of fatty tissue, covered with coarse hair. This structure is the mons pubis. Extending from the mons pubis to the perineal floor are two large folds called the labia majora (large lips). These protect the inner structures and contain sensory nerve endings and an assortment of sebaceous (oil) and sudoriferous (sweat) glands. Directly under the labia majora lie the labia minora (small lips). These are smaller folds of tissue, devoid of hair, that merge anteriorly to form the prepuce of the clitoris. The clitoris is comparable to the male penis and is composed of erectile tissue that becomes engorged with blood during sexual stimulation.

The space enclosing the structures located beneath the labia minora is called the vestibule. It contains the clitoris, the urinary meatus, the hymen, and the vaginal opening.

Accessory glands

Bilateral to the urinary meatus lie the paraurethral, or Skene’s, glands, the largest glands opening into the urethra. These glands secrete mucus and are similar to the male prostate gland. Bilateral to the vaginal opening are two small, mucus-secreting glands called the greater Bartholin’s glands (vestibular), which lubricate the vagina for sexual intercourse.

Perineum

The area enclosing the region containing the reproductive structures is referred to as the perineum. The perineum is diamond shaped and starts at the symphysis pubis and extends to the anus.

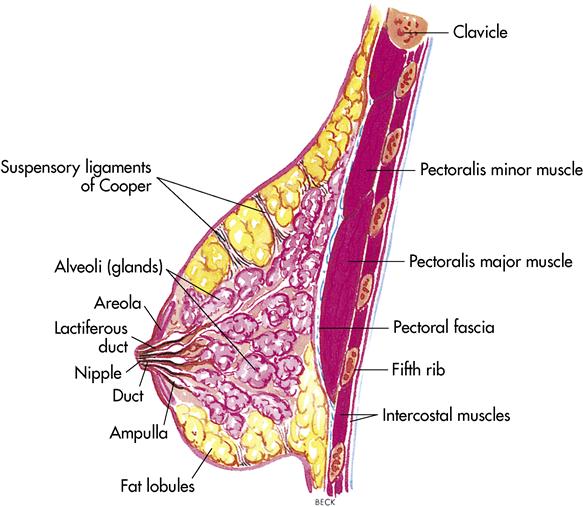

Mammary glands (breasts)

The breasts are attached to the pectoral (chest) muscles. Breast tissue is identifiable in both sexes. During puberty, the female breasts change their size, shape, and ability to function. Each breast contains 15 to 20 lobes that are separated by adipose tissue. The amount of adipose tissue is responsible for the size of the breast. Within each lobe are many lobules that contain milk-producing cells; these lobules lead directly to the lactiferous ducts that empty into the nipple (Figure 12-6).

The nipple is composed of smooth muscle that allows it to become erect. The dark pink or brown tissue surrounding the nipple is called the areola. Milk production does not start until a woman gives birth. At this time, under the influence of prolactin, the milk is formed. The hormone oxytocin allows milk to be released.

Menstrual cycle

Menarche, the first menstrual cycle, usually begins at approximately 12 years of age. Each month, for the next 30 to 40 years, an ovum matures and is released about 14 days before the next menstrual flow, which occurs on average every 28 days. If fertilization occurs, menstrual cycling subsides and the body adapts to the developing fetus.

Generally, the menstrual cycle is divided into three phases: (1) menstrual, (2) preovulatory, and (3) postovulatory. This discussion uses the example of a 28-day cycle. On days 1 through 5 of the cycle, the endometrium sloughs off, accompanied by 1 to 2 ounces of blood loss. The anterior pituitary gland begins to release follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH); as the level of FSH increases, the egg matures within the graafian follicle (a pocket or envelope-shaped structure where the ovaries prepare the ovum [Figure 12-7]). From days 6 through 13 (preovulatory phase), estrogen is released from the maturing graafian follicle. This estrogen causes vascularization of the uterine lining. On day 14, the anterior pituitary gland releases luteinizing hormone (LH), which causes the rupture of the graafian follicle and release of the mature ovum. The fingerlike projections of the fallopian tubes (fimbriae) sweep the ovum into the fallopian tube. Once this mature ovum has been expelled, the follicle is transformed into a glandular mass called the corpus luteum. During days 15 through 28 (postovulatory phase), the developing corpus luteum releases estrogen and progesterone. If pregnancy occurs, the corpus luteum continues to release estrogen and progesterone to maintain the uterine lining until the placenta is formed, which then takes over the job of hormonal release. If pregnancy does not occur, the corpus luteum lasts 8 days and then disintegrates. Normally the corpus luteum shrinks and is replaced by scar tissue called corpus albicans. At this point the hormone level decreases over several days and menstruation starts again.

Effects of normal aging on the reproductive system

Menopause usually occurs in women between 35 and 60 years of age. The average age is 51. Whether it occurs earlier or later, menopause should not be considered abnormal. Cigarette smoking and living at high altitudes are associated with early menopause. During menopause the menstrual flow ceases and hormone levels decrease. A woman may experience “hot flashes” (sudden warm feelings), which are caused by the decrease in estrogen production. Changes also occur in the reproductive organs. The vagina loses some of its elasticity, and the breasts and vulva lose some adipose tissue, resulting in decreased tissue turgor. The bones may also become brittle and prone to osteoporosis.

Men have no menopausal period. Sperm production decreases but does not cease. In later years, testosterone production decreases, but not dramatically.

Basically, as long as the older individual is healthy, nothing in the aging process prohibits normal sexual function (see Life Span Considerations box).

Human sexuality

Sexuality and sex are two different things. Sexuality is often described as the sense of being a woman or a man. It has biologic, psychological, social, and ethical dimensions. Sexuality influences life experiences, and sexuality is influenced by life experiences. The term sex has a more limited meaning. It usually describes the biologic aspects of sexuality such as genital sexual activity. Sex may be used for pleasure or reproduction. As a result of life’s changes or by personal choice, sexual activity may be absent from a person’s life for brief or prolonged periods. Some persons may choose to remain celibate.

The process by which people come to know themselves as women or men is not clearly understood. Being born with female or male genitalia and subsequently learning female or male social roles seem to be factors, though these do not explain differences of sexuality and sexual behavior. Such variations are more understandable if the nurse remembers that sexuality is intertwined with all aspects of self.

Sexual identity

Biologic identity, or the differences between men and women, is established at conception and further influenced at puberty by hormones. Gender identity is the sense of being feminine or masculine. As soon as the infant is born (and sometimes before), the outside world labels the child as a girl or boy. Adults adjust their behavior to relate to a female or male infant. These varied patterns of interaction influence the infant’s developing sense of gender identity.

Children explore and seek to understand their own bodies. Combining this information with the way in which they are treated, they begin to create an image of themselves as a boy or as a girl. By 3 years of age, children are aware that they will remain boys or girls and that no outward change in their appearance will alter this. This understanding is part of the development of self-concept.

Gender role is the manner in which a person acts as a woman or man. Many believe that society influences female and male behavior and is thus the primary source of femaleness or maleness. Because society encourages certain behaviors according to one’s gender, differences between individuals’ sexual behaviors develop. Most likely, as with other human behaviors, sexual behavior is a combination of many interacting biologic and environmental factors.

Cultural factors can be key ingredients in defining sex roles. Some cultures tightly dictate roles as feminine or masculine (e.g., the man is the breadwinner, and the woman is the caregiver). Other groups have more flexible role definitions and encourage men or women to explore a variety of roles without labeling the behavior as feminine or masculine.

Sexual orientation is the clear and persistent erotic desire of a person for one sex or the other. There are heterosexual, homosexual, lesbian, and bisexual individuals, but the origins of sexual orientation are still not understood. Biologic theorists describe orientation in genetic terms, meaning it is determined at conception. Psychological theorists attribute orientation to early learning experiences, believing that cognitive processes are the determining factor. Still other theorists state that genetics and environment both play roles in the development of sexual preference.

For some people the inward sense of sexual identity does not match the biologic body. These people are known as transgenders. Researchers do not clearly understand how this mismatch occurs. Transgenders do not see their sexual identity as a choice; it is a clear and persistent orientation dating back to early childhood. In contrast, most homosexual men and women define themselves as satisfied with their gender and social roles; they simply have a persistent desire for their same sex.

A transvestite is most often a heterosexual man who periodically dresses like a woman; however, a transvestite may be a homosexual. Cross-dressing is usually done in private and kept secret even from those who are closest to him.

Because sexuality is linked to every aspect of living, any sexual choice involves personal, family, cultural, religious, and social standards of conduct. Ideas about ethical sexual conduct and emotions related to sexuality form the basis for sexual decision making. The range of attitudes about sexuality extends from a traditional view of sex only within marriage to a point of view that allows individuals to determine what is right. Sexual choices that overstep a person’s ethical standard may result in internal conflicts.

Some people may judge sexual decisions as moral or immoral solely on religious standards; others view any private sexual act between consenting adults as moral. People will always have differing beliefs about sexual ethics. The debate over sexuality-related issues such as abortion, contraception, sex education, sexual variations, and premarital or extramarital intercourse will continue. Nurses must maintain a nonjudgmental attitude while caring for all patients.

Taking a sexual history

Because overall wellness includes sexual health, sexuality should be a part of the health care program. Yet health care services do not always include sexual assessment and interventions. The area of sexuality can be an emotional one for nurses and patients (see Health Promotion box).

Giving patients information about sexuality does not imply agreement with specific beliefs. Patients need accurate, honest information about the effects of illness on sexuality and the ways that it contributes to wellness. Nurses need to provide this information without influencing patient choices. Professional behavior must guarantee that patients receive the best health care possible without diminishing their self-worth. Promotion of self-education and honest examination of sexual beliefs and values can help in reducing sexual bias.

Although there is no single approach to taking a sexual history, certain principles make it more comfortable for both the patient and the nurse (Box 12-1):

• Avoid overreacting or underreacting to a patient’s comments; this aids in truthful data collection.

• Move from the less sensitive to the more sensitive areas. This will promote nurse-patient comfort.

• At the end of the sexual history, ask if the patient has additional questions or concerns.

A brief sexual history assessment can be made and included in the nursing history through the use of three questions (Box 12-2). The questions may be adapted to address illness, hospitalization, life events, or any other relevant matter that influences or interferes with sexual health. The questions may also be adjusted to find out what the patient expects to happen as a result of procedures, medications, or surgery. Often the nurse does not need to ask the last two questions because many patients voice their concerns about masculinity, femininity, and sexual functioning without further encouragement.

Nurses may intervene in sexual problems among patient populations through four strategies: (1) educating patient groups likely to have sexual concerns, (2) providing anticipatory guidance throughout the life cycle, (3) promoting a milieu conducive to sexual health, and (4) validating normalcy about sexual concerns.

Several self-help groups and other organizations publish easy-to-read pamphlets on sexuality (see Health Promotion box). These pamphlets can often be purchased for a nominal fee and given to patients. Most pamphlets can be obtained directly from state or local chapters. Contact chapters of other self-help groups about the availability of resources for patients, such as newsletters that address sexuality.

Nurses can also write their own pamphlets for patients. Although this requires some effort, it may provide additional incentive for staff to address sexuality.

Illness and sexuality

Illness may change a patient’s self-concept and result in an inability to function sexually. Medications, stress, fatigue, and depression also affect sexual functioning. Alcohol abuse can lead to a reduced sex drive and inadequate sexual functioning.

Lack of interest or desire for sexual activity often occurs when patients are preoccupied with symptoms of illness. Most often these sexual symptoms disappear as patients recover from the acute phase of illness and resume sexual activity. However, some illnesses—such as diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal disease, prostate cancer, certain types of prostate surgery, spinal cord injuries, and heart disease—may cause patients concern or may result in actual inabilities with sexual function.

Changes in the nervous system, circulatory system, or genital organs may lead to sexual health problems. Spinal cord injuries can interrupt the peripheral nerves and spinal cord reflexes that involve sexual responses. But spinal cord–injured men and women also have reported having satisfying orgasms in spite of complete denervation of all pelvic structures.

Sexual dysfunction of a patient with diabetes mellitus can occur when the disease is not well controlled, but the dysfunction generally disappears when the lack of control is diagnosed and treated. Approximately half of the men who have diabetes mellitus are impotent, generally because of poor control. Sexual counseling is important to (1) provide accurate information about the sexual aspects of the disorder, (2) dispel the patient’s incorrect assumptions and expectations, and (3) give advice to improve the patient’s sexual self-esteem and dispel the guilt frequently found in both partners.

A mastectomy results in both physical and emotional trauma. In addition to the resultant disfigurement, a patient must also grapple with (1) how to cope with cancer, (2) how the operation will affect her relationship with her spouse or significant other, (3) how to relate to the strangeness of her own body, and (4) how her sex life will be affected. Problems that arise with pelvic irradiation for cancer of the cervix are much harder to treat than those of mastectomy; the entire physiology of the vagina is altered by the radiation, causing a true loss of function. With a mastectomy the only function lost is the ability to nurse an infant. The goal for the patient and her partner is to face the issue in a straightforward manner, acknowledging the diagnosis and discussing their true feelings. If feelings are repressed rather than shared, both the patient and her significant other may suffer. Therapeutic counseling before surgery can aid the patient’s and partner’s acceptance and recovery after surgery.

Laboratory and diagnostic examinations

Diagnostic tests for women

A physician performs the pelvic examination, which involves visualization and palpation of the vulva, the perineum, the vagina, the cervix, the ovaries, and the uterine surfaces. During the pelvic examination, specimens are frequently obtained for diagnostic purposes. The bimanual pelvic examination progresses from the visualization and palpation of the external genital organs for edema and irritations to an inspection for abnormalities of the internal organs. To visualize internal organs, the physician inserts a vaginal speculum. The physician may perform a rectovaginal examination to evaluate abnormalities or problems of the rectal area and the posterior internal organs (Box 12-3).

Colposcopy

Colposcopy (colpo, vagina or vaginal; and scopy, observation) provides direct visualization of the cervix and vagina. Prepare the patient for a pelvic examination and explain the purpose of the procedure. The physician inserts the vaginal speculum, followed by insertion of the colposcope for inspection of the area. The color of the tissue, presence of growths and lesions, and condition of the vascularity are observed and specimens obtained as necessary.

Culdoscopy

Culdoscopy is a diagnostic procedure that provides visualization of the uterus and adnexa (uterine appendages, i.e., the ovaries and fallopian tubes). Explain the purpose and the method of procedure. Prepare the patient for the vaginal operation with preoperative instructions. The patient is given a local, spinal, or general anesthetic. After the anesthetic is administered, the patient is assisted to a knee-chest position. The culdoscope is passed through the vaginal wall in back of the cervix. The area is examined for tumors, cysts, and endometriosis. During the procedure, conization (removal of eroded or infected tissue) may be done. This procedure is generally done on an outpatient basis. After the operation, assess for bleeding, assess vital signs, and monitor voiding.

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy (examination of the abdominal cavity with a laparoscope through a small incision made beneath the umbilicus) provides direct visualization of the uterus and the adnexa. Preparation of the patient includes insertion of a Foley catheter to maintain bladder decompression for an open view. The procedure is done with a general anesthetic. The physician grasps the cervix with forceps and inserts a lighted laparoscope through the incision. Carbon dioxide may be introduced to distend the abdomen for easier visualization. If a biopsy is to be done or organs are to be manipulated, a second incision may be made in the lower abdomen to allow for instrument insertion. The ovaries and fallopian tubes are observed for masses, ectopic pregnancy, adhesions, and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Tubal ligations may be done using this procedure. Instruct the patient of the probability of shoulder pain afterward because of carbon dioxide introduced into abdomen.

Papanicolaou (pap) test (smear)

Papanicolaou (Pap) test (smear) (a simple smear method of examining stained exfoliative peeling and sloughed-off tissue or cells) is most widely known for its use in the early detection of cervical cancer. Scrapings of secretions and cells are taken from the cervix and spread on a glass slide. The slide is sprayed with a fixative and sent to the laboratory for analysis. It is important that slides be properly labeled with the date, time of the last menstrual period, and whether the woman is taking estrogens or birth control pills. Instruct patients not to douche, use tampons, use vaginal medications, or have sexual intercourse for at least 24 hours before the examination. Collect careful menstrual and gynecologic history.

The American Cancer Society (ACS) (2009a) highly recommends that every woman begin annual Pap tests within 3 years after becoming sexually active or no later than 21 years of age. Women should be tested every year (regular Pap test) or every 2 years (thin prep Pap test). Women age 30 years or older who have had three normal Pap tests in a row may choose to be screened every 2 to 3 years instead of annually. Women age 70 years or older who have had three or more normal Pap tests in a row and no abnormal test results in the past 10 years may decide to stop having cervical screenings altogether. Also, women who have had a hysterectomy may stop having cervical cancer screenings (unless their surgery was done as a treatment for cervical cancer or precancerous cells).

Thin prep Pap tests may slightly improve the detection of cancers and greatly improve the detection of cervical precancers. Thin prep Pap tests also reduce the number of tests that need to be repeated.

The physician may recommend more frequent testing for women with a history of multiple sexual partners or sexually transmitted infections (STIs), a family history of cervical cancer, or those whose mothers used diethylstilbestrol (DES) during pregnancy.

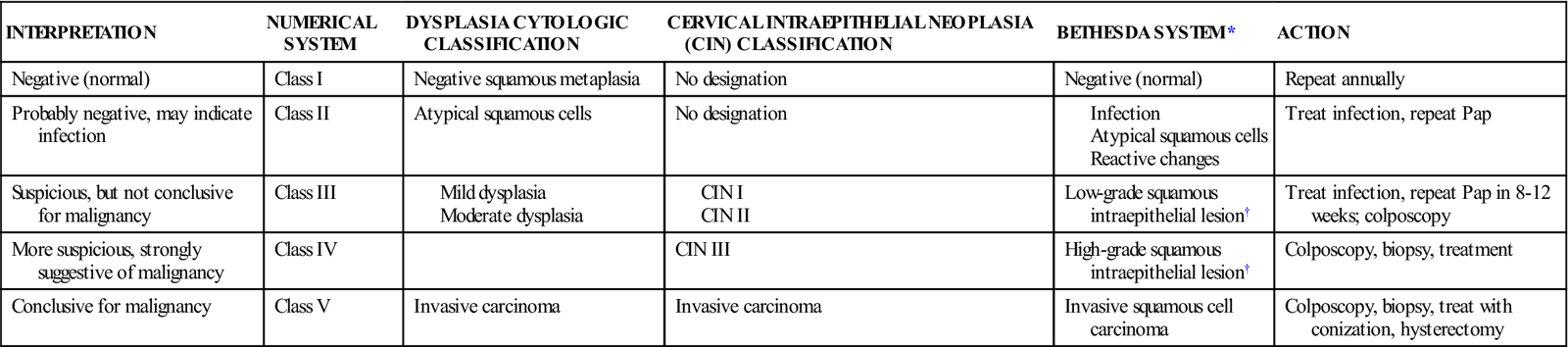

Table 12-1 provides a comparison of interpretation classifications of the cytologic findings and treatment recommendations. The Bethesda system is preferred because it allows better communication between the cytologist and the clinician. The Bethesda system evaluates the adequacy of the sample (e.g., satisfactory or not satisfactory for interpretation) and provides a general classification of normal or abnormal and a descriptive diagnosis of the Pap smear. Although the classification system may vary, clinicians agree it is important to monitor Pap smears and ensure proper follow-up, including treatment of vaginal infections and colposcopy if necessary.

Table 12-1

Pap Test Interpretation Classifications and Action

| INTERPRETATION | NUMERICAL SYSTEM | DYSPLASIA CYTOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION | CERVICAL INTRAEPITHELIAL NEOPLASIA (CIN) CLASSIFICATION | BETHESDA SYSTEM* | ACTION |

| Negative (normal) | Class I | Negative squamous metaplasia | No designation | Negative (normal) | Repeat annually |

| Probably negative, may indicate infection | Class II | Atypical squamous cells | No designation | Treat infection, repeat Pap | |

| Suspicious, but not conclusive for malignancy | Class III | Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion† | Treat infection, repeat Pap in 8-12 weeks; colposcopy | ||

| More suspicious, strongly suggestive of malignancy | Class IV | CIN III | High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion† | Colposcopy, biopsy, treatment | |

| Conclusive for malignancy | Class V | Invasive carcinoma | Invasive carcinoma | Invasive squamous cell carcinoma | Colposcopy, biopsy, treat with conization, hysterectomy |

*The Bethesda system is the preferred system.

†The Bethesda Working Group suggests that “these two new terms encompass the spectrum of terms currently used to delineate the squamous cell precursors to invasive squamous carcinoma, including the grades of CIN, the degree of dysplasia, and carcinoma in situ.”

Pap tests have long been used to look for cervical cancer and precancerous cells. Cervista 16/18 and Cervista HPV HR are recently introduced tests for detecting the high-risk types of human papillomavirus (HPV) that are most likely to cause cervical cancer by looking for pieces of their deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) in cervical cells. These DNA-based tests, in conjunction with the Pap test, have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (2009b) for women ages 30 and over with slightly abnormal Pap test results to find out if more testing or treatment may be needed.

Biopsy

Biopsies are procedures in which samples of tissue are taken for evaluation to confirm or locate a lesion. Tissue is aspirated by special needles or removed by forceps or through an incision.

A breast biopsy is performed to differentiate benign or malignant tumors. Breast biopsy is indicated for patients with palpable masses; suspicious areas appearing on mammography; and persistent, encrusted, purulent, inflamed, or sanguineous discharge from the nipples. The biopsy is performed by fine-needle aspiration (FNA); stereotactic or ultrasound core biopsy, under local anesthetic; or surgical biopsy, with general or local anesthetic. In an FNA, fluid is aspirated from the breast and expelled into a specimen bottle. Pressure is placed on the site to stop bleeding, then an adhesive bandage is applied. In an open surgical biopsy, an excisional biopsy is usually performed in a portion of the breast to expose the lesion and then remove the entire mass (Lewis et al., 2007). Another procedure called stereotactic and ultrasound core biopsy is a reliable diagnostic technique to obtain breast biopsy if an abnormal mass is seen on mammogram. A mammogram is used to find the lesion, the skin is anesthetized, and a small superficial incision is made. A biopsy gun device is fired into the lesion and removes a core sample of the mass. Compared with an open surgical biopsy, this procedure produces less scarring, uses only a local anesthesia, has reduced costs, and is done on an outpatient basis (Cleveland Clinic, 2009). Specimens of selected tissue may be frozen and stained for rapid diagnosis. The wound is sutured and a bandage applied. Observe the incision site for bleeding, tenderness, and erythema.

A cervical biopsy is done to evaluate cervical lesions and to diagnose cervical cancer. The biopsy is generally done without anesthesia. The colposcope is inserted through the vaginal speculum for direct visualization, the cervical site is selected and cleansed, and tissue is removed. The area is then packed with gauze or a tampon to check the blood flow.

An endometrial biopsy is performed to collect tissue for diagnosis of endometrial cancer and analysis for infertility studies. The procedure is generally performed at the time of menstruation when the cervix is dilated and cells are more easily obtained. The cervix is locally anesthetized, a curette is inserted, and tissue is obtained from selected sites of the endometrium.

Other diagnostic studies

Conization of the cervix is used to remove eroded or infected tissue or confirm cervical cancer. A cone-shaped section is removed when the mass is confined to the epithelial tissue. After surgery the area is packed with gauze to control bleeding. The patient is observed for bleeding and generally discharged from the hospital the same day.

Dilation and curettage (D&C) (scraping of material from the wall of a cavity or other surface; performed to remove tumors or other abnormal tissue for microscopic study) is a procedure used to obtain tissue for biopsy, to correct cervical stricture, and to treat dysmenorrhea. The patient is placed under general anesthesia, the cervix is dilated, and the inside of the uterus scraped with a curette. Packing may be inserted for hemostasis, and a perineal pad is applied for absorption of drainage. After vaginal packing is removed, instruct the patient to monitor for excessive vaginal bleeding or malodorous drainage.

Cultures and smears are collected to examine and identify infectious processes, abnormal cells, and hormonal changes of the reproductive tissue. Specimens collected for smears are prepared by spreading the collected smear on a glass slide and covering it with a second slide or spraying it with a fixative. Handle specimens with aseptic techniques and take care to avoid the transfer and spread of organisms. Cultures are taken from exudates of the breast, the vagina, the rectum, and the urethra. STIs and mastitis are diagnosed by isolation of the causative organisms. Treatment is prescribed according to the results of the culture.

Schiller’s iodine test is used for the early detection of cancer cells and to guide the physician in doing a biopsy. An iodine preparation is applied to the cervix, and glycogen, which is present in normal cells, stains brown. Abnormal or immature cells do not absorb the stain. Unstained areas may be biopsied. This method of detection is valuable but not entirely reliable, since normal cells sometimes lack glycogen and malignant tissue sometimes contains glycogen. After the procedure the patient should wear a perineal pad to avoid stains on the clothing.

Radiographic examinations are performed to detect abnormal tissue, locate abnormal structures, and observe patency of ducts.

Hysterograms and hysterosalpingograms are studies for visualizing the uterine cavity to confirm (1) tubal abnormalities (adhesions and occlusions), (2) the presence of foreign bodies, (3) congenital malformations and leiomyomas (fibroids), and (4) traumatic injuries. The patient is placed in the lithotomy position. A speculum is inserted into the vagina, a cannula is inserted through the speculum into the cervical cavity, and a contrast medium is injected through the cannula. As the contrast medium progresses through the cavity, the uterus and fallopian tubes are viewed by a fluoroscope and films are taken.

Mammography is radiography of the soft tissue of the breast to allow identification of various benign and neoplastic processes, especially those not palpable on physical examination. Digital mammography is a newer technique that allows a clear and more accurate image; it involves digitally coding x-ray images into a computer (Lewis et al., 2007). It is believed that the average breast tumor is present for 9 years before it is palpable. Digital mammography is helpful as a screening procedure. The ACS (2009a, b) recommends baseline mammograms for women between ages 35 and 39, with annual mammograms after age 40.

When the mammography procedure is scheduled, advise the patient to refrain from using body powders, deodorants, and ointments on the breast areas, since this could cause false-positive results. Before the procedure give the patient a gown and ask her to remove jewelry and upper garments. The technician asks the patient to sit or stand in an upright position and rest one breast on the radiographic table. A compressor is placed on the breast, and the patient is asked to hold her breath as an anterior view is taken. The machine is rotated, the breast is again compressed, and a lateral view is taken. This procedure is repeated on the other breast. The patient may be asked to remain until the radiographic films are read.

Because of the greater density of breast tissue, mammography is less sensitive in younger women, which may result in more false-negative results. About 10% to 15% of all breast cancers can only be detected by palpation and cannot be seen on mammography. Even if mammogram findings are unremarkable, all suspicious masses should be biopsied.

Ultrasound is a helpful diagnostic tool to differentiate a benign tumor from a malignant tumor. It is useful in women who have dense breasts with fibrocystic changes. Unlike a mammogram, an ultrasound will not detect microcalcifications (Lewis et al., 2007).

The ACS (2007b) recommends, in addition to annual screening with mammography, the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for women with a 20% to 25% or greater lifetime risk of developing breast cancer. An MRI is not recommended as a routine screening for all eligible women due to its high cost and greater risk of false positives as compared to mammograms.

In pelvic ultrasonography, high-frequency sound waves are passed into the area to be examined, and images are viewed on a screen; this is similar to a radiographic film. Ultrasound is useful in detecting foreign bodies (such as intrauterine contraceptive devices [IUDs]), distinguishing between cystic and solid tumor bodies, evaluating fetal growth and viability, detecting fetal abnormalities, and detecting ectopic pregnancy. Generally it is noninvasive, safe, and painless. Encourage the patient to drink fluids beforehand. Explain that a full bladder is essential to the accuracy of the test.

Tubal insufflation (Rubin’s test) involves transuterine insufflation of the fallopian tubes with carbon dioxide. The procedure enables evaluation of the patency of the fallopian tubes and may be part of a fertility study. Tubal insufflation takes approximately 30 minutes and is usually performed on an outpatient basis. If the tubes are open, the gas enters the abdominal cavity. A high-pitched bubbling is heard through the abdominal wall with a stethoscope as the gas escapes from the tubes. The patient may complain of shoulder pain from diaphragmatic irritation. In this case a radiographic film shows free gas under the diaphragm. If the tubes are occluded, gas cannot pass from the tubes, and the patient will not report pain.

All pregnancy tests, regardless of method, are based on detection of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which is secreted in the urine after the fertilization of the ovum. Regardless of method, it is important to know that the tests do not indicate whether the pregnancy is normal. False-positive results may occur.

Serum CA-125 is a tumor antigen associated with ovarian cancer, since it is positive in 80% of such cases. CA-125 antigen levels in the blood decrease as the cancer cells decrease. CA-125 has been touted as a way to detect primary ovarian cancer, but unfortunately it does not do so. CA-125 is useful mainly to signal a recurrence of ovarian cancer and to follow the response to chemotherapy treatment. If chemotherapy causes a progressive decline in CA-125, it is an accurate indicator of a good response and is a good prognostic sign. Other conditions—such as endometriosis, PID, pregnancy, gynecologic cancers, and cancer of the pancreas—may result in an elevation of serum CA-125.

Diagnostic tests for men

Testicular biopsy

Testicular biopsy is a means to detect abnormal cells and the presence of sperm. The testing can be done by aspiration or through an incision. The anesthetic used depends on the technique. Postbiopsy care measures consist of scrotal support, ice pack, and analgesic medications. Warm sitz baths for edema may also be helpful. Instruct the patient to call the physician if bleeding or elevated temperature occurs.

Semen analysis

Semen analysis can be performed to substantiate the effectiveness of a vasectomy, to detect semen on the body or clothing of a suspected rape victim, and to rule out or determine paternity. The procedure is generally one of the first tests performed on men to evaluate fertility. Semen can be collected for testing by manual stimulation, coitus interruptus, or the use of a condom.

Prostatic smears

Prostatic smears are obtained to detect and identify microorganisms, tumor cells, and even tuberculosis in the prostate. The physician massages the prostate by way of the rectum, and the patient voids into a sterile container prepared with additive preservative. The specimen is collected and a smear is prepared in the laboratory.

Cystoscopy

In cystoscopy a man’s prostate and bladder can be examined by passing a lighted cystoscope through the urethra to the bladder. Before the procedure, obtain a signed consent form and educate the patient concerning the procedure. The procedure is usually performed without anesthesia, but a local anesthetic may be instilled into the bladder. After the cystoscopy the patient may have pink-tinged urine and frequency and burning on urination. Provide comfort by warm sitz baths, heat, and a mild analgesic (Lewis et al., 2007). Cystoscopy can be done for both men and women to detect bladder infections and tumors.

Other diagnostic studies

Other diagnostic studies for men include the rectal digital examination and the prostate-specific antigen (PSA), a highly sensitive blood test. PSA, which is normally secreted and disposed of by the prostate, shows up in the bloodstream in cancer of the prostate and in a harmless condition called benign prostatic hyperplasia or prostate enlargement. The normal PSA is less than 4 ng/mL. Elevated PSA levels in the bloodstream mean something needs to be checked. Even a slight increase in PSA level needs to be closely monitored; referral to a urologist for a biopsy is recommended. Still another study is the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) test. The normal ALP is 35 to 142 units/L for men, and 25 to 125 units/L for women. These specific tests are useful in diagnosing benign prostatic hypertrophy, prostatic cancer, bone metastasis in prostatic cancer, and other disease conditions (Box 12-4).

-m

-m n-

n- -R

-R –

– ,

,  NG-k

NG-k r,

r,  S-t

S-t -l

-l ,

,  n-

n- -R

-R -j

-j ,

,  -M

-M -s

-s s,

s,