CHAPTER 2. Evidence-Based Practice

Mary E. Hagle, PhD, RN, AOCN® and Patricia Senk, BSN, RN

Standards of Practice, 10

Definition of Evidence-Based Practice, 11

Components of Evidence-Based Practice, 11

EBP at the Point of Care: Nurse and Patient, 18

Models of EBP, 18

EBP Support and Opportunities, 18

Summary, 19

Nursing practice requires current best evidence to provide care that meets our standards, partners with patients, and is effective and efficient. Nurses must question their personal beliefs, health care myths, and traditional practices that are not based on research and current best evidence. How many nurses continue to lock a peripheral IV with heparin because this is the way “it has always been done” or the order is written for this? It has been more than 17 years since two meta-analyses were published with the practice recommendation that 0.9% sodium chloride is an effective locking solution for peripheral IVs (Goode et al., 1991 and Peterson and Kirchhoff, 1991). Seventeen years is the time it takes to translate research findings into practice; based on this fact, all peripheral IVs in adults in acute care settings with nonthrombogenic catheters should be locked with 0.9% sodium chloride. Is your practice research based? An interesting survey would be to validate this research-based practice in the United States and in other developed countries. Unfortunately, most nursing practice assessments or interventions do not have a meta-analysis, let alone two, as their current best evidence. Thus obtaining current best evidence is a process composed of key steps for the individual nurse, the health care organization, professional nursing organizations, and nursing as a profession.

The use of best evidence in practice is now a measurable goal, as identified by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). They set a goal that by 2020, “90% of clinical decisions will be supported by accurate, timely, and up-to-date clinical information, and will reflect the best available evidence” (IOM, 2007, p. ix). This goal is the result of a 2001 recommendation that care needs to be effective and based on the best available scientific knowledge (IOM, 2001). There is also acknowledgment that evidence is more than expert consensus-based guidelines yet not necessarily only randomized controlled trials. Current best evidence is just that—the synthesized knowledge a nurse has at the time to provide effective care. As the body of evidence is synthesized and gaps are identified, research is justified to provide support for our care. The knowledge loop is closed when new evidence is integrated into current systems in a way that is timely and efficient.

Evidence needs to be transparent for both nurses and patients. Nursing practice is the care of patients or clients; patients are one half of the partnership. Every nursing theory involves a nurse and a patient. Current best evidence is implemented with the patient’s decision and is tempered by the patient’s personal knowledge and skills, beliefs, preferences, and values in the context of the situation. It is the nurse’s knowledge, skill, experience, and expertise that integrate these components for a quality health care outcome.

STANDARDS OF PRACTICE

The standards of both the American Nurses Association (ANA) and the Infusion Nurses Society (INS) recognize the importance of incorporating best current evidence into nursing. Standard 13 of the ANA’s Scope and Standards of Practice (ANA, 2004) requires that “the registered nurse integrate research findings into practice” (p. 40). Nurses practice according to this standard by using the best evidence available to guide their decisions and actively participate in research activities. A continuum of research activities can include the following: identifying a clinical problem; participating in data collection; using research in policies, procedures, and standards of practice; and critically appraising and interpreting research for use in the practice setting (ANA, 2004). Nursing’s Social Policy Statement (ANA, 2003) identifies the nurse’s relationship with, and obligation to, the patient. It calls upon the nurse to (1) use research to expand the science of nursing; (2) use evidence-based knowledge when assessing, planning, implementing, and evaluating care; and (3) use evidence to improve care (ANA, 2003). The Infusion Nursing Standards of Practice (INS, 2006) promote evidence-based practice and research. Standard 18 specifically addresses the utilization of research “to expand the base of nursing knowledge in infusion therapy, to validate and improve practice, to advance professional accountability, and to enhance evidence-based decision making” (INS, 2006, p. S24). This is accomplished by participating in research activities, critically appraising research outcomes, and implementing research findings into clinical practice.

DEFINITION OF EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

The components of current best evidence with the patient’s decision-making and personal knowledge carried out by nurses with expertise have been espoused by medical and nurse authors as comprising evidence-based practice (EBP). The Institute of Medicine (2001, p. 147) legitimized EBP for all health care practitioners with their definition:

Evidence-based practice is the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values. Best research evidence refers to clinically relevant research, often from the basic health and medical sciences, but especially from patient-centered clinical research into the accuracy and precision of diagnostic tests (including the clinical examination); the power of prognostic markers; and the efficacy and safety of therapeutic, rehabilitative, and preventive regimens. Clinical expertise means the ability to use clinical skills and past experience to rapidly identify each patient’s unique health state and diagnosis, individual risks and benefits of potential interventions, and personal values and expectations. Patient values refer to the unique preferences, concerns, and expectations that each patient brings to a clinical encounter and that must be integrated into clinical decisions if they are to serve the patient.

EBP provides a framework and culture for quality health care. Each component needs to be supported in the full sense of the word by the organization and by a culture of daily practice by the individual nurse. The micro level of EBP is at the nurse-patient relationship. In daily practice, the current best evidence needs to be integrated through computerized clinical decision support information for access by nurses and into care plans that are patient-centered and based on appropriate assessments and risk factors (Hook, Devine, Lang, 2008; Institute of Medicine (IOM), 2007 and O’Neill et al., 2006). Unnecessary traditional practices need to be eliminated based on current best evidence. Imagine a nurse at 2 am faced with an unusual and unique patient situation. In an EBP environment, the nurse is able to rapidly access research-based resources and has the skills and knowledge to evaluate the evidence at hand to effectively care for his/her patient. In addition, the current best evidence is provided for the patient in language the patient understands with content to aid his or her decisions (Figure 2-1).

|

| FIGURE 2-1 EBP in action. (From Aurora Health Care, Milwaukee, Wis.) |

At the system or organizational level, EBP is supported and expected. Financial and human resources are available to obtain and appraise evidence, translate it into practice, and evaluate effectiveness. Current best evidence is incorporated into policies, procedures, professional standards, protocols, care plans, and computerized clinical decision support. Education is widespread and easily available for all health care personnel and patients/families to understand EBP and the processes that support it. System level outcomes are transparent for nurses and patients.

There are two additional levels, meso and macro, for EBP that are gaining attention. The meso level involves negotiations between health care organizations and payers. “In the future, the implementation of evidence-based procedures will become an important criterion for the financial reimbursement of nursing provision by health-insurance funding” plans, which may lead to high-quality nursing care that is effective and cost-efficient (Hasseler, 2006, p. 222). The political machinations or strategies are at the macro level, that is, the level where health policy, health care funding, and other measures are decided (Hasseler, 2006, p. 223): “If the nursing profession fails to become involved in the debate on drawing up and developing evidence-based nursing procedures and standards in the new programs, other professional groups will step in and take over the fields of activity….”

Using current best evidence can be an automatic and an active process. By accessing EBP policies, procedures, professional standards, protocols, and care plans that are already in place, nurses are incorporating best evidence into practice through an automatic mechanism. For example, because fluoride is added to drinking water, tooth decay in children and adults is prevented without active participation at the time. Nurses also may be actively involved in EBP through any of the steps, such as identification of the key clinical question, the initial evidence review, appraisal, or integration into organizational processes. EBP also engages nurses through the triggers, alerts, decisions, or tasks within a computerized clinical decision support mechanism. Regardless of the practice setting (long-term care, acute care, home health, primary care, or elsewhere), it is critical that EBP is the culture of daily practice for nurses.

COMPONENTS OF EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Having a culture of EBP involves, at a minimum, understanding each component of EBP. Expertise develops as nurses and teams become more familiar with EBP. The following sections address the components of EBP: best evidence; clinician experience and expertise; and patient beliefs, preferences, and values in the context of the practice setting and current patient situation.

BEST EVIDENCE

Evidence is defined as “a thing or things helpful in forming a conclusion or judgment”; it is the proof. As such, evidence may come from a variety of sources including published and unpublished reports, internal quality improvement project summaries, and expert opinion.

The best evidence is not necessarily a research report, because research may not have been done or reported in your area of interest. Best evidence can be evaluated against objective criteria and categorized into a hierarchy of usefulness. The body of evidence is synthesized for the practice recommendation. The steps to identify, obtain, evaluate, and synthesize the evidence are important to ensure reaching the best evidence for the topic.

Asking the clinical question

The search for evidence begins with asking a clinical question. Nurses’ clinical questions come from a variety of sources, which may include a newly published study or clinical guideline, a novel clinical experience, an unexpected outcome, a questioning of tradition, or unclear benchmarking data. A structured format during question formation assists nurses, novice to expert, in including the key elements in their question. These elements are the study population, which is similar to your patients, the intervention of interest and the comparison intervention, and the outcome of interest. One method to aid in forming the question is the “PICO” ( Patient population; Intervention; Comparison; Outcome) method (Nollan, Fineout-Overholt, Stephenson, 2005), as outlined in Table 2-1. This format for the clinical question also assists in identifying the key terms that might be used during the literature search.

| PICO method | Explanation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Patient population | Individual or groups of individuals you are interested in studying | Adults in acute care setting with short-term central venous access device |

| Intervention | The intervention in which you are interested | Saline solution for locking |

| Comparison | The intervention that you want to use for comparison | Heparin for locking |

| Outcome | The effect of the intervention | The length of time the catheter is patent with both locking solutions |

The patient population identifies the group of individuals who are the focus of the question and about whom information is needed. The population may be individuals with a specific disease or condition, or of a certain age, gender, or ethnicity. For example, your clinical interest is the adult population in the acute care setting with a short-term central venous access device (CVAD). If the pediatric population were included in the search, the evidence obtained would not be useful to answer the clinical question. Knowing the population helps to narrow down the potentially large amount of literature to be reviewed and will allow the focus to be on what is important to the clinical practice area. For example, if the interest is in the effect of an intervention on adult males and the study included only adult females, the results may not pertain to the question. Including additional words commonly used to describe a disease, treatment, or device is also helpful when searching for evidence. A CVAD is sometimes called a subclavian catheter in clinical practice; both of these terms could be used when performing a literature search. Of course, using the accepted subject heading is recommended as well, and each nurse and librarian has their own method for doing searches. As a result, directions on doing literature searches are beyond the scope of this chapter.

The specific intervention or interventions of interest should be identified, and may include a treatment, a screening assessment, risk factor, or prevention strategy. In the preceding example, the interest was in the locking solution for a CVAD. Your institution uses saline solution, but several articles have been reviewed related to the use of heparin when locking a CVAD. Identifying this intervention will help exclude literature that examines the recommended replacement time for a CVAD. While this may be a clinically important question, the desired clinical question is focused on the recommended locking solution. Use only literature that addresses the desired clinical question; if it is not related, exclude it from the list of evidence to consider.

A comparison group can be a group that receives no treatment or several groups in which each receives a different treatment or intervention. The comparison group in the example is the patient group receiving the heparin solution for locking.

The outcome of interest is the effect of the treatment. In the preceding example, the outcome or effect is patency of the CVAD; the treatment option is either saline solution or heparin. In the example, identifying this specific outcome will exclude literature that examines the infection rate of the CVAD. After identifying the appropriate content for each element of PICO, the clinical question is developed: Should saline solution or heparin be used when locking a CVAD in adult patients in the acute care setting?

Searching for evidence

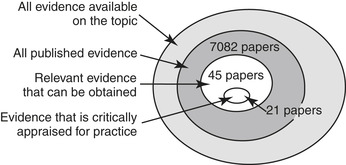

Once the key clinical question is identified, it is used to guide the evidence search. Working with a librarian is advised, especially if there is a lack of previous experience in completing a literature search. An overwhelming amount of evidence is often available; many times there are thousands of papers. The reality of how difficult it can be to find relevant evidence that answers a clinical question is demonstrated in Figure 2-2. The outer ring identifies all the evidence that is available on a topic or problem of interest. This includes both published and unpublished evidence, ranging from rigorous studies, to expert opinion, to internal quality improvement reports. Only a portion of the evidence that exists is published. Published sources include journals, conference proceedings, a dissertation or thesis, and textbooks. When a literature search is completed, only a portion of all available published evidence is obtained; this may be due, in part, to the specific search words that were used. Additionally, only some of the available evidence may be obtained; costs of retrieving dissertations or requesting articles may be a deterrent, along with the time lag to obtain such evidence.

|

| FIGURE 2-2 Finding the evidence. |

Once the available evidence is obtained, an initial review is done. Although an article may be identified when using specific search terms, it does not mean that the sample, tool, or disease state is the same as the patient population or area of interest. Each article needs to be examined for its relevance to answering the clinical question. If interested in the rate of phlebitis for peripheral intravenous infusions (PIVs) with routine catheter replacement every 96 hours in adults in the acute care setting, one search would yield 7082 papers. When limiting this search to the last 10 years, papers only in English, with adults, and human populations, then the evidence that can be obtained and reviewed would include 45 papers. These papers would be reviewed for pertinence to the topic, population, and setting; for example, several papers are eliminated since the catheters in the study were peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) and not PIVs. The 21 remaining papers are then critically appraised, content is abstracted onto an evidence table, and the quality of the evidence is rated. High-quality applicable evidence would be synthesized and used in a practice recommendation.

A database of guidelines or systematic reviews is a good place to start searching for evidence (Box 2-1). Many of the databases have tutorials to assist clinicians in searching for information on their topic. These databases are easily accessible via the Internet and the guidelines are free and downloadable. Other databases contain citations and abstracts for journals specific to a discipline, such as CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) for nurses and allied health professionals. The published papers can be purchased by individuals or through a library subscription. The school, hospital, or local library can help locate articles and may have subscriptions to journals that are unfamiliar to the nurse or researcher. Often, university alumni have access to the school’s library and search services, as another means to obtain resources.

Box 2-1

SAMPLE DATABASES FOR A LITERATURE SEARCH

| Database | Subject matter |

|---|---|

| National Guideline Clearinghouse www.guideline.gov/ | Provides guidelines on health care topics; initiative of U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) |

| Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews www.cochrane.org/reviews | Provides systematic reviews on health care topics; independently supported; based in U.K. |

| National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence www.nice.org.uk/ | Provides national guidelines (guidance) on health promotion and treatment; an independent organization based in U.K. |

| PubMed www.pubmed.gov | Includes citations from MEDLINE and other journals; service of U.S. National Library of Medicine |

| Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) | Includes journals from nursing and allied health; by subscription |

| MEDLINE | Includes journals from medicine, nursing, and dentistry; by subscription |

| PsycINFO | Includes literature from psychology and related disciplines; by subscription |

National organizations interested in health care quality and patient safety are another source for evidence. Several national organizations, as well as professional clinical organizations, have websites with additional sources of evidence and may provide practice guidelines they have endorsed (Box 2-2). These lists are not all-inclusive and other summaries sometimes are published (Dee, 2005). More organizations are taking responsibility to support practice with best evidence. As quality and safety become major outcomes, bodies of evidence and synthesis are needed to identify best practice and stop ineffective or possibly harmful practices.

Box 2-2

ORGANIZATIONS PROVIDING EVIDENCE SUMMARIES, STANDARDS, AND OTHER EVIDENCE

| National organizations | Website address |

|---|---|

| Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) | www.ahrq.gov |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | www.cdc.gov |

| Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) | www.ihi.org |

| National Quality Forum (NQF) | www.qualityforum.org |

| TRIP Database: Turning Research into Practice | www.tripdatabase.com |

| Sample professional nursing organizations | Website address |

| American Association of Critical-Care Nurses | www.aacn.org |

| American Nurses Association | www.nursingworld.org |

| Infusion Nurses Society | www.ins1.org |

| Oncology Nursing Society | www.ons.org |

Critical appraisal and rating the evidence

Each paper, report, or quality improvement project can be a type of evidence. The evidence that is used depends on the body of evidence available and the quality of each piece of evidence. A health care organization may have results from a quality improvement project or benchmarking data that also can be used to support the use of a specific intervention. Initially, evaluate the available evidence by considering the following questions. Some papers will be put aside after this review.

• What are the setting, sample, and interventions used in the article? Are the setting and sample the same, or similar, to the subject of interest? There would be no need to review articles from the home care setting if the population of interest is in the acute care setting. The interventions of interest or technology need to be similar to the clinical question.

• Is the article from a peer-reviewed journal? Articles in a peer-reviewed journal have gone through a rigorous content review for scientific and statistical accuracy, which usually involves individuals who are experts in the field.

• Who are the authors, and what are their credentials? Are the author’s experts in the field? While not every author has to be an expert, what are the individuals’ credentials? If it is a research study, is one author an individual with the education to perform research?

• Are there any conflicts of interest? Did a group or corporation that may have an interest in the results sponsor the study?

When the evidence is pared after this initial review, it is sometimes helpful to sort the evidence chronologically and determine what is the most recent information on the topic. Another way of becoming familiar with the evidence is to sort by a hierarchy of research design, which is the plan for conducting the study. It is the manner of selecting the sample and administering the intervention. Generally, evidence such as a meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are considered the highest rank of research design; however, these are also the fewest types of evidence available. Evidence such as a case study has a low ranking in the hierarchy of research design. Because research used to support nursing practice encompasses a variety of research designs, it is important to include qualitative design in a hierarchy (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2005). A common hierarchy of research designs and their definitions are outlined in Box 2-3.

Box 2-3

HIERARCHY OF RESEARCH DESIGNS AND THEIR DEFINITIONS

| Research design | Broad definition |

|---|---|

| Meta-analysis | A specific statistical analysis to combine findings of several studies examining the same phenomenon to determine the overall effect of an intervention |

| Systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) | A methodology to identify, appraise, and synthesize RCTs on the same phenomenon |

| Randomized controlled trial (RCT) | A study where subjects are randomly assigned to groups; one group receives a treatment and the other group does not; the groups are blinded to the treatment, or in other words, they do not know which treatment they are receiving |

| Correlational design | A study that focuses on the relationship between two variables in the same population |

| Case control design | A study of two matched samples at the same time; one sample has the characteristic or variable of interest and one does not |

| Cohort design | A study of one sample that is followed over time to describe and identify a relationship between a variable and an outcome |

| Descriptive design | An examination of a phenomenon as it naturally occurs; there is no manipulation of variables. Data collected may include: Quantitative, such as a survey: descriptive analysis of numerical dataQualitative: analysis of verbal or written data, such as interviews, textbooks, or observational notes |

| Case study | An exploration and description of a single unit, such as a person, organization, community, or group at one point in time or over time |

Data from Collins S et al: Finding the evidence. In DiCenso A, Guyatt G, Ciliska D, editors: Evidence-based nursing: a guide to clinical practice, St Louis, 2005, Mosby; and Burns N, Grove S: The practice of nursing research: conduct, critique, and utilization, ed 5, St Louis, 2005, Saunders.

Research studies are only one type of evidence. Other evidence high in the rating hierarchy, but not a research design, is a clinical practice guideline based on a systematic review or a systematic review of one phenomenon using studies and other evidence on the topic. A systematic review is a rigorous methodical search, review, and critical appraisal of research evidence, by two or more researchers to answer a specific clinical question (Collins et al., 2005 and Guyatt et al., 2008). Other review types are available too, such as an integrative review or a narrative review, all having varying levels of evidence and rigor in their development. These types of evidence may be available on a topic when a meta-analysis or systematic review of RCTs is not. The benefit of these types of evidence is that they merge findings from several studies and other sources on the same clinical topic. A variety of practice guidelines are available, and it is important to determine how the recommendations were developed. A guideline may be based on a rigorous systematic review or it may be based on consensus of experts. If none of these evidence types are available, then look for a single RCT. If an RCT is not available, then look for correlational, case control, descriptive, qualitative, or other studies. Last, examine expert opinions, reports, or quality improvement projects.

Once the main pieces of evidence are identified and sorted, a critical appraisal is done of each piece. A critical appraisal, or a quality analysis, of the evidence examines the study or paper for three domains: design, methodology, and how it was analyzed, all to minimize bias (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2002). Criteria in each of these domains may include, for example, blinding, adequate sample size, and preciseness of the results (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), 2002, Ebell et al., 2004 and Schünemann et al., 2008). Often a checklist is used to rate each criterion, such as whether the subjects were randomized or if appropriate statistical analysis was used. As part of the critical appraisal system, a value may be assigned to each piece of evidence, or a hierarchy of quality is established, so that some evidence is more valuable as compared to the remaining evidence. This is helpful when looking at the final body of evidence. There are many systems for the critical appraisal and rating of individual evidence, especially quantitative studies, as well as available systems for guidelines and qualitative evidence (Box 2-4). When selecting a system, consider one that is clear, concise, reproducible among various research teams, and understandable to clinicians as well as researchers. This is an opportunity for professional nursing organizations to adopt or develop a common system that crosses specialties.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access