CHAPTER 3. Quality Management

Grace P. Sierchio, RN, MSN, CRNI®, CPHQ

The Impetus for Change, 23

Defining and Perceiving Quality, 23

Leaders in Quality Management, 24

Approaches to Quality Management, 27

Standards: Statements of Expected Quality, 30

Methods of Measuring Performance, 32

Methods of Displaying and Analyzing Data, 36

Methods (Cycles) for Improving Performance and Quality, 38

Tools for Planning Improvements, 41

Tools for Documenting Improvement Actions, 43

Integrating Quality Management, 44

Future Opportunities and Challenges, 45

Summary, 47

Quality management is an organizational culture committed to achieving excellence. It is not a singular activity or a singular department or project team. Instead, it is an ongoing set of processes that are the very “fabric” of an organization. The National Association of Healthcare Quality defines “total quality” as “an attitude, an orientation that permeates an entire organization, and the way that an organization performs internal and external business” (Claflin, 1998).

In health care, quality management seeks to improve customer outcomes by improving the processes of patient care. Many “models” or approaches to quality management exist. New conceptual models are developed and new tools and methodologies wax and wane in popularity. In the end, they all strive to achieve the same goal: they seek to improve customer satisfaction and outcomes by producing products or services that are consistent, reliable, free of defects, safe, and effective. They also seek to improve the operational and financial health of the organization by improving internal processes and minimizing cost while maximizing potential profitability.

When studying quality management, the reader must consider that the provision of a health care service to a patient is distinctly different from the manufacture of a health care product. The number of variables is greatly increased. As a result of patient condition, co-morbidities, and the complexity of health care programs, the process of producing a service for a patient is much less consistent and predictable than the production of a product for a patient. The ordering, planning, insertion, and monitoring of a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) are markedly different than the manufacture of the PICC.

With that said, the ultimate goal in the management of service quality is to reduce inconsistency, and to strive for achieving a “perfect” service, free of defects (errors) and resulting in the desired patient outcome without causing complication or harm.

Infusion nursing is a service. It is a service grounded in evidence-based professional nursing practice that seeks to contribute to the overall desired patient outcome. That outcome might be the consistent maintenance of a continuous subcutaneous infusion site so that pain is successfully treated, or the successful completion of chemotherapy resulting in health status improvement. It might be the successful initiation of home parenteral nutrition resulting in a return to an ideal body weight, or the successful completion of intravenous antibiotics resulting in the elimination of cellulitis. Whatever the ultimate patient goal might be, the infusion nurse’s contribution is to provide services coordinated with other disciplines towards that goal. The infusion nurse’s goal is to provide quality care (services) so that the patient can meet his or her goal.

An organization with a true quality management culture involves every discipline, organizational level, and department in the process of improvement. The infusion nurse must act as the advocate for patient outcomes and safety related to infusion equipment and therapies by actively participating in the process. The infusion nurse is the “SME” or “subject matter expert” when an improvement study or project involves infusion therapy. No one is better equipped and experienced to provide expertise in the improvement of infusion services.

This chapter seeks to educate the infusion nurse about common models and methods for quality management. It provides an overview of basic quality improvement techniques. Practitioners who are interested in learning more are encouraged to contact quality and health care related organizations, such as the National Association of Healthcare Quality (NAHQ), for additional information and resources.

Throughout this chapter, there are numerous references to The Joint Commission (TJC). Quality management requirements have always been part of TJC’s accreditation process and TJC standards are one of several national and international benchmarks for quality in health care. There are a growing number of organizations that can accredit hospitals and alternative site organizations. All have standards related to the improvement of services. TJC standards are only one method of achieving improvement. However, since many hospitals and home care organizations maintain TJC accreditation, their quality improvement standards still serve as an industry standard, and their published guidelines for quality improvement will be described frequently in this chapter.

THE IMPETUS FOR CHANGE

It has been acknowledged that for decades the quality of health care in the United States has been greatly mismanaged. Patient morbidity and mortality continued to rise through the 1980s and 1990s, while at the same time the national expenditures for health care skyrocketed (Institute of Medicine, 2000). Health care industry leaders, reacting to adverse events occurring to patients in hospitals and in other health care settings, called for immediate research to determine the degree of our nation’s health care quality crisis. In 2000 the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published the first of a set of groundbreaking papers entitled To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. The study results provided a sober look at the overusage, underusage, and misusage of health care services in the United States. In 2001 the IOM published Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. It described strategies that might be used to effectively “fix” what was perceived as a “broken” health care delivery system (Institute of Medicine, 2001). The Joint Commission’s publication of its Agenda for Change drastically shifted the focus in accredited organizations from structural issues (e.g., written policies) to process and outcome consistency and included the development of accreditation standards mandating effective quality management programs (TJC, 1990). These papers created a ripple effect through the health care industry, resulting in increased attention being given to quality assurance and quality improvement. The publication of these documents proved to be a turning point in the history of health care quality in the United States.

DEFINING AND PERCEIVING QUALITY

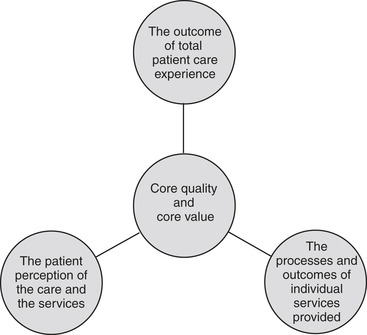

While health care leaders agreed that quality needed to be improved, the concept of quality as it pertains to health care services remained difficult to define. Quality has been broadly described by many as the comprehensive positive outcome to a product. In health care, however, the service is multifaceted and multidimensional, which contributes to different perceptions of quality. Five patients and five clinicians might all be asked, “What is a high-quality venipuncture?” and you might receive seven different responses. Our perception of quality is frequently influenced by our own expectations of outcome, needs, prior experiences, and emotional and cognitive status at the time the question was asked. A precise definition of quality health care attempts to acknowledge these differences and includes the services delivered and their perceived value to the consumer (Figure 3-1).

|

| FIGURE 3-1 Elements of health care quality. |

PATIENT CARE

Quality of care has been described as the effective technical application of medical science to prevent, diagnose, treat, and cure disease. This is the simplest description of quality because it concentrates on the technical aspects of patient care. Theoretically, “care” is a product or process that can be observed, measured, tested, and controlled through statistical methodologies.

Any discussion of quality principles can become confusing since different organizations, authors, and quality improvement methods define and describe terms differently. This chapter defines the term “patient care” as the total sum experience provided to a patient by the health care system. The system might be one facility (e.g., a hospital), or it might be coordinated home care organizations (e.g., a home care agency coordinating with a home infusion pharmacy). Patient care can include both services and products. It can include both products that are “consumed,” such as dressing kits, and products that are durable medical equipment, such as an infusion pump. It can include educational, technical, and support processes. An example would be a patient that receives patient education about self-administering IV antibiotics, instructions concerning IV equipment and supplies; and financial counseling regarding the funding for the home infusion services.

Many departments, disciplines, and organizational “layers” contribute to the patient care provided. In the example in the previous paragraph, nurses, equipment managers, pharmacists, and delivery staff each contributed services and/or products that were part of the total patient care experience. Taking the example one step further, different layers of organizational structure contributed to the patient care. From the CEO that approved the purchase of new infusion pumps, to the project team that designed new patient education materials, to the first-line providers of care that packed and delivered the supplies, every layer of the organization contributed their “service” to the total patient care experience.

To measure the “quality” of patient care, the optimal method would somehow measure how the coordinated services of everyone involved resulted in the intended patient outcome and did not result in any complications or adverse event. Likewise, it would measure not only the clinical outcome but also the patient’s perception of the total patient care experience.

It is significant to note that, since services provided by different departments or disciplines make up the total patient care experience, the failure by one service to deliver “quality” can influence the patient’s perception of the whole experience. A classic example is the patient that is provided the most technologically advanced medical care by the most caring and professional staff, but that has a negative perception of the entire hospitalization experience because his or her food plate always arrives cold. It is the classic “weak link in the chain” concept.

PERCEIVED QUALITY OF SERVICES

As stated, multiple services make up “patient care.” Each service provided by an individual clinician or department, in turn, has its own desired procedure outcome based on established practice standards and protocols or pathways developed by consensus.

When the infusion nurse provides a peripheral IV catheter insertion (service) to a patient, the intended outcome is to insert the catheter aseptically, on the first attempt, with minimal discomfort, in an appropriate catheter site. These procedure outcomes are based on researched and published performance standards for the specific procedure (service) provided.

Quality patient care is the major product delivered in health care, but service is the subjective aspect that influences the consumer’s perception of quality. Each service provided must meet two basic goals to be successful. The service must be provided correctly in terms of the technical aspect, and the service must be provided in a way that leaves the patient with the sense that it was performed correctly, with professionalism and care. The nursing procedure may be technically correct, but the patient judges the care according to how the service was delivered. In the previous example, the nurse can insert the catheter, meeting all of the listed criteria (such as aseptic placement and first attempt, for example), but if done so in an unfriendly or brusque manner the patient’s perception of the quality of that service will be influenced.

TJC refers to this as patient perception of care. Measuring patients’ perceptions of the care they receive is an important component in the performance improvement program of any health care organization.

PERCEIVED VALUE OF SERVICES

Perception of “quality” and perception of “value” are intertwined but are different. “Value” is a function of the quality of the service in relation to its cost. Historically, patients might have been insulated from the cost of their health care because their health insurance provider paid the cost and the patient’s portion was minimal or waived. In today’s health care arena, patients are responsible for an increasingly larger portion of their health care costs. Because of larger deductibles, heftier co-payments, and a growing list of noncovered services and medications, consumers are becoming increasingly analytical about their health care options, the perceived value, and their out-of-pocket costs. Therefore consumers are now more conscious of the value of the care they receive, and they expect the highest caliber care in relation to the cost. Taking this concept a step further, the “customer” in today’s health care is frequently not just the patient, but also the insurance company or payment source. Third-party payers that are accredited by the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA) must maintain quality control and quality management standards. They, in turn, expect the same of the providers of care that bill for the services. This is the basis of managed care, which attempts to create a balance of acceptable value and a controlled cost of health care.

Governmental payers have spoken loudly in the past several years by establishing long awaited quality standards. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) published quality standards for Part B Suppliers in 2006. The document clearly demonstrates the government’s dedication to controlling the cost of health care while, at the same time, assuring the quality of the care provided to Medicare beneficiaries. Specific standards within that document mandate the establishment of formal quality management programs that include mandatory third-party accreditation and patient outcome monitoring (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2006).

“Pay for Performance” or (P-4-P in quality management terms) is another quality/value concept that is currently being studied by governmental payers and may some day be used by public and private sector payers of health care services in both hospitals and alternative settings. The concept of P-4-P is simply that providers of health care are reimbursed in accordance to how well they provide the care. Financial incentives are provided to organizations that achieve clinical and other benchmarks of performance (DeBoer, Iyenger, Dudhela, 2008). It is, basically, a patient outcome–based sliding scale for payments. Although at first this might seem bizarre, remember that health care in the United States is one of the few industries where a provider can bill and be entitled to payment even if the service was provided in an incorrect manner and resulted in poor outcomes and adverse events. Instinctively, we as an industry know this has to change. As part of the P-4-P concept the health care industry has taken on the mission of developing performance measures that can be used to compare the performance of one organization to that of another. To accurately and validly compare performance and establish the benchmarks, all organizations must collect the same performance measures in the same way. These measures are known as “core performance measures” (TJC, 2008d). Further discussion of core measures and performance measures follows later in this chapter.

LEADERS IN QUALITY MANAGEMENT

Three names often mentioned in discussions of quality are Juran, Crosby, and Deming. These leaders defined, refined, and popularized the concept of quality in the manufacturing world, but their teachings serve as the groundwork for the quality initiative in health care. These “thought” leaders were historically the founders of the quality movement in the United States as well as in other countries. Many new “thought” leaders have expanded upon their work in recent years, creating industrial and service models. Some of these new “thought” approaches to quality will be reviewed as well as the “foundation” theories.

J. M. JURAN

Dr. Juran was among the first to recognize that product quality requires careful planning, control, and improvement. These basic managerial processes are known as the Juran trilogy. Although his teachings were initially applied to Japanese business, Juran’s principles of quality planning, quality control, and quality improvement have since been used in American industry (Juran, 1989).

Quality planning

Quality does not occur by accident; it is the result of meticulous preparation. The major aspects of planning are determining customer needs and developing products that meet those needs. The primary emphasis is on external customers, who are the end users of the product, but consideration must also be given to the internal customers, who assist in product development.

Quality control

The process of quality control requires that product performance be evaluated and compared with product goals, and that the differences between performance and goals be resolved. To achieve quality control, all employees must be accountable and make use of a feedback loop.

Quality improvement

Quality improvement requires organized change to attain unprecedented levels of performance. It represents a transition from little q (a narrow scope of quality limited to clients and products) to big Q (a broad concept of quality that defines customers as those who are affected and products as all goods and services). In addition, it exchanges the reactionary practices of “putting out fires” and “ready, fire, aim” for a proactive, systematic process that concentrates on improving all aspects of business. One of the best known methods for achieving quality improvement is by means of quality councils, also known as quality circles.

Juran’s teachings regarding the involvement of every level of worker in the improvement process are carried forward today in many new models of quality management. It is a foundation of every successful quality system.

PHILIP B. CROSBY

Crosby is a management consultant who worked his way up through the ranks of business. He introduced the philosophy of “do it right the first time,” which conveys his belief that quality is free; it is the nonquality products that cost money because they require rework. To explain the concept, Crosby used the phrase zero defects. This expression emphasizes that compliance with defined standards and specifications is necessary to achieve quality; poor quality is the result of lack of compliance and nonconformance. However, it was also Crosby’s contention that conformance requirements must be based on input from the workers who produce the product (Crosby, 1979).

Most quality experts in health care agree that the concept of zero defect is not easily applicable to health care services. As stated earlier, providing health care services is, by its nature, very different from manufacturing a product. Although the latter can be controlled by specifications and procedures to the degree that a 100% perfection rate can be attained, the unpredictability of human physiology, psychology, and circumstances make this a challenge in health care, including infusion nursing.

However, “thought” leaders in health care have been reexamining some of Crosby’s teachings and adapting them for use in health care. Six Sigma, a growing model for quality improvement in health care, is based on Crosby’s foundational teachings and will be described later.

To place Crosby’s teachings in the context of infusion nursing, we can use the example of a PICC insertion program. When planning the program, the team manager faced the decision of purchasing task lighting for the procedure rooms. She selected lighting (Lamp B) that was significantly less expensive than the recommended lamp (Lamp A). She perceived that Lamp B was a better value because it was 40% less expensive. When purchasing six lamps, the “savings” were significant. However, 4 months into the program the lamps began to fail, producing flickering during the procedures. The infusion nurses or their technical assistants frequently needed to interrupt the insertion to replace the lamp or reposition it to provide adequate light. In eight situations, the interruption required restarting the procedure with a new insertion kit. The team manager quickly realized that the “value” of the lamps was poor, and the rework needed to correct the problem cost more than the reduced lamp prices.

W. EDWARDS DEMING

Dr. Deming, the “guru” of quality, is best known for helping the Japanese achieve world-class quality in product manufacturing, but many American industries have since adopted his teachings. Like Crosby, Deming’s philosophy of quality is based on the premise that problems with quality reside predominantly in an organization’s systems and processes, not in its employees (Deming, 1989). Deming’s strategy stresses continuous quality improvement and is based on the 14-point system for managing quality (Box 3-1).

Box 3-1

DEMING’S 14-POINT SYSTEM FOR MANAGING QUALITY

1. Create consistency of purpose for product improvement. The vision of the organization must be directed at continual refinement of the product. For an organization to become and remain competitive, there must be a strategy for achieving continuous improvement.

2. Adopt the new philosophy. Mistakes and negativism cannot be tolerated. Instead, the philosophy of the organization must be dedicated to improving quality.

3. Cease dependence on inspection. Quality is the result of improved production processes, not the identification of defective products. Prevention reduces the need for inspection to produce a quality product.

4. Avoid awarding business on price alone. If the concentration is on quarterly dividends alone, quality and productivity suffer.

5. Constantly improve. Quality improvement is a continual process, not a one-time activity. Improvement is the result of a never-ending pursuit to reduce waste and improve systems.

6. Institute training. Workers must be properly trained to perform effectively and efficiently. The organization must invest in training; failure to do so may be detrimental to survival of the organization.

7. Institute leadership. Management and leadership are different. Managers tell the worker what to do; leaders create a vision and guide the workers in achieving progressively improved outcomes.

8. Drive out fear. Fear inhibits innovation. If workers are fearful of expressing their ideas or asking questions, the job may continue to be done ineffectively or incorrectly.

9. Break down barriers between staff areas. Competition and rivalry between departments stem from conflicting goals. A unity in mission and promotion of teamwork within and among departments help identify opportunities for improvement.

10. Eliminate slogans, extortions, and targets for workforce. Quality is not a management-defined slogan and is not achieved by coercing workers to achieve optimal results. Workers must be involved in identifying methods to improve quality and determining how these expectations are communicated to others.

11. Eliminate numerical quotas. Quotas are counterproductive because they concentrate on numbers instead of processes that can be improved.

12. Remove barriers to pride of workmanship. Workers need to be empowered to have pride in the quality of their work. To accomplish this, the organization must eliminate barriers, such as defective materials, that hinder the quality of the product.

13. Institute vigorous program of education. Quality improvement activities require that both managers and workers be educated about statistical techniques and team-building exercises.

14. Take action to achieve transformation. All workers must be involved in the change from quality control to quality improvement. The change must be led by a dedicated team of those in top management who have established a precise plan of action to improve quality.

“14-Point System,” from Deming Management at Work by Mary Walton, ©1990 by Mary Walton. Used by permission G.P Putnam’s Sons, a division of Penguin Putnam, Inc.

Using our PICC program example to illustrate some of Deming’s philosophy, the team manager, through quality control, detects that the incidence of unsuccessful first attempts is increasing. She evaluates the problem and sees that it is not limited to one particular nurse but to several. By meeting with the staff and using quality improvement methods (e.g., root cause analysis, brainstorming, and process mapping, to be described later), the team manager realizes that the increase is not due to nursing error, but is due to a combination of a recent change in PICC insertion kits ( materials), poor task lighting ( materials), and a change in how patients are positioned in the procedure chairs ( methods or procedures).

BILL SMITH

Bill Smith is frequently referenced in quality management literature as a new thought leader in quality management. Bill Smith is considered to be the “Father of Six Sigma.” Six Sigma is loosely based on the work of Crosby and the concept of “zero defect.” Smith, who was the quality assurance director for the Land Mobile Products Sector of Motorola, developed this method of quality management. Its premise is that, through the proper control of variables and the consistent application of internal processes, you can limit the number of defects in the products you produce to less than 3.4 per 1 million opportunities. For example, you could manufacture 1 million IV catheters and less than 3.4 in the million would be defective. Six Sigma uses statistical models to measure and analyze defects. It is rapidly becoming one of the most commonly used quality management models in industries internationally (George et al., 2005 and Gygi et al., 2005; Pande, Neuman, Cavanagh, 2000). Jack Welch (then the well-known and respected industry leader and CEO of General Electric) and others quickly recognized the potential value and profitability of using Six Sigma techniques and helped make them mainstream in industry. There are many authors and quality leaders who have examined how to adapt Six Sigma for health care, and many feel its use will grow in health care over the next decades.

FREDERICK WINSLOW TAYLOR

F. W. Taylor was a mechanical engineer. His contribution to quality management thought was the principle of increased efficiency and reduced waste through the use of standardized procedures. This concept of increasing both quality and profitability by using standards and by reducing waste was coined the “Efficiency Movement” (Carreira, 2005). It was adopted by industry leaders such as John D. Rockefeller and Henry Ford. Ultimately it served as a foundation for a current quality management philosophy known internally as “lean manufacturing.”

Lean manufacturing has recently been popularized by the Toyota Motor Corporation through its use of the Toyota Product System (TPS). It emphasizes the improvement of the quality of a product through the most efficient manufacturing processes that emphasize standardization, minimal waste, and constant measurement and monitoring. Lean manufacturing principles are often connected to Six Sigma principles, creating a hybrid that is called “Lean Six Sigma.”

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR STANDARDIZATION (ISO)

Lastly, a discussion of quality management history and theories would be incomplete without discussion of ISO standards. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is an international organization that publishes standards for a large scope of manufacturing and service industries. To become ISO registered, a company must apply the principles of ISO standardization in the workplace, and use the standards to continually improve the products and services provided to its customers (Anton and Anton, 2006).

ISO 9000 and ISO 9001 registration are internationally accepted symbols of good quality management practices within a company. Throughout the world, ISO has been commonly used in manufacturing. Although a small number of health care organizations in the United States are ISO certified, the U.S. health care sector still has not fully embraced the use of ISO 9001 to improve patient care. However, its impact has been seen in improving products and equipment manufactured for patients.

NATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AND ACCREDITING BODIES

The interest in improving health care in the United States and in controlling the escalating costs of health care has lead to a tremendous growth in the number, size, and activity of organizations and public and private institutions that aim to improve health care outcomes and efficiencies. Some aim to educate practitioners and consumers, while others aim to develop theories, strategies, and tools for quality management.

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) is an example. IHI is an independent not-for-profit organization whose mission is to improve health care globally through research and education. This organization holds conferences that bring together some of the most progressive thought leaders in health care quality, and strives to teach organizations how to use quality improvement tools to improve outcomes while controlling costs. Additional information is available at www.ihi.org.

The National Quality Forum (NQF) is another highly active and visible organization in health care improvement. The NQF is a not-for-profit membership that seeks to improve outcomes, stabilize or reduce costs, and improve efficiencies in our health care industry. The NQF has also been very involved in the review and evaluation of core performance measures for various health care sectors, including home care. This organization was established as a public-private partnership organization. Its membership includes representatives from consumers, practitioners, employers/purchasers, labor unions, health care associated industries, and national, regional, and local health care organizations. Additional information is available at www.qualityforum.org.

The value of third-party accreditation was underscored in 2006 when the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) established a mandatory requirement for accreditation in order to participate in the CMS Part B Supplier program (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2006). This program provides payment for durable medical equipment for enrolled Medicare beneficiaries with Part B coverage. Included in Part B is reimbursement for infusion therapy pumps and other infusion-related devices. Organizations providing these products now must be accredited by a third-party accreditor that has been granted deemed status by CMS. Accreditors include The Joint Commission (TJC), Accreditation Commission for Health Care (ACHC), Community Healthcare Accreditation Program (CHAP), and others. The accrediting agencies work to develop meaningful patient care standards for health care organizations, as well as to educate practitioners and consumers regarding health care quality and effectiveness.

APPROACHES TO QUALITY MANAGEMENT

With the increasing emphasis on quality in health care, organizations have initiated programs to control, ensure, assess, improve, and manage quality. The leadership team will select a quality management model based on a variety of factors including cost, the availability of local expertise, and possibly the quality “trend” at the time. Regardless of which model of quality management is selected, the end result should be that the organization embraces methods that continually improve patient care. Defining some of the terms used is a challenge because of the different models. The same term might be used differently by two different quality management (QM) models. This section will offer typical definitions and descriptions of the various terms. The terms quality control, quality assurance, quality assessment, continuous quality improvement, and total quality management are not synonymous but may appear to “overlap,” much like circles in a Venn diagram.

QUALITY CONTROL

Quality control (QC) is the evaluation of the production of a product or a service, by means of statistical methodologies. This approach consists of “on-line” inspection that compares a random sample of products with a predetermined, acceptable level of defects. Primary components of QC include data collection and statistical analysis of data. It was originally used for the inspection of manufacturing equipment and manufactured products, and has been referred to as statistical quality control. Six Sigma, described earlier in this chapter, is based on the principles of quality control.

Using the PICC program example to illustrate quality control, two elements of the program can be reviewed. The first is the PICCs used, and the second is the average wait time for insertion (one product and one service). Quality control principles would take a random sampling of catheters from the assembly line and would test the internal diameter French size. The aggregate, or averaging of the French sizes for the sample of catheters, would be calculated and would yield statistics used by the factory’s quality manager. Using quality control for the service component is similar. The PICC program for this large facility places 60 PICCs per day, and an average (statistical mean) of 280 per week. The acceptable standard set by the PICC team for an insertion wait time was 5.5 hours. The program’s quality committee meets weekly and randomly audits 30 insertion records per week. The results show that the statistical average for the week was 4.3 hours. The quality circle discusses the results, evaluates that there is no need for further action, and documents the result on an ongoing trend chart.

The major disadvantages of QC are its emphasis on statistical methods and the “pass/fail” nature of the process. Data analysis should serve as the basis for decision making, but in quality control, there is a tendency for the statistical tools to become an end in themselves. Results are monitored and reported after goods or services have been produced, without emphasis on improving outcomes. In this case, the PICC team is happy with a wait time of 4.3 hours and no discussion ensues on how to, over time, gradually reduce the wait time to improve patient care.

Hence, this tool-oriented approach is being replaced by problem-oriented and results-oriented techniques (Juran, 1989).

QUALITY ASSURANCE

It was once assumed that most health care was of high quality, so the primary objective of “traditional” quality assurance was to ensure that the acceptable level of care was maintained. Quality assurance (QA) may be defined as the determination of the degree of excellence through monitoring and evaluation. Before the publication of the IOM reports, quality assurance typically meant retrospective chart reviews by a dedicated quality assurance staff member. The reviews focused on the documentation of certain specific aspects of care. “Thresholds” of compliance were arbitrarily set, and typically no activity was taken to move the threshold to improve quality. A PICC program at that time might have audited 10% of 3 months of charts to see if the catheter length was documented. A threshold of 95% would have been set, and the program would “pass” or “fail.” In reality, what was being assessed was not the patient care, or even the specific PICC service, but instead the documentation of a particular element of a PICC insertion.

When the IOM reports were published, health care industry thought leaders accepted that a major change in how we manage quality must occur. The industry began to adopt components of the industrial models of quality management. During the transition, quality programs in health care progressed from quality assurance to quality improvement, and have now progressed towards total quality management in progressive organizations.

In 1990 TJC developed the Agenda for Change, which initiated the transition from QA to continuous quality improvement. The goal was to create outcome monitoring and evaluation processes to help organizations improve the quality of care provided (JCAHO, 1990). Consistent with this change, TJC began the paradigm shift by renaming their chapter on quality Quality Assessment and Improvement. TJC explained that the underlying rationale for the shift to assessing and improving quality was to overcome several weaknesses inherent in QA practices. First, QA is often focused solely on one specific aspect of a service provided by one particular department or discipline. It does not tend to focus on the total patient care experience. It does not reflect the interdisciplinary or cross-service nature of patient care, and the interrelated managerial, governance, support, and clinical processes that affect patient care outcomes. Each of these tendencies inhibits the organization’s ability to improve processes and thus improve patient care outcomes. Table 3-1 highlights the differences between QA and quality improvement (QI).

| Quality assurance | Quality improvement |

|---|---|

| Problem oriented | Results oriented |

| Focuses on inspection | Focuses on identification and correction |

| Uses “snapshot” data to evaluate performance | Uses “trend” data to identify appropriate areas for action |

| Focuses on negative aspects of care | Focuses on positive aspects of care |

| Monitors nursing tasks | Monitors patient processes and outcomes |

| Retrospective | Concurrent |

| Evaluates documentation | Evaluates care, services, and outcomes |

| Random monitoring | Planned, systematic monitoring |

| May be unrelated to standards | Based on standards and benchmarks |

| Fixed process | Dynamic process |

| Reactionary | Proactive |

| Responsibility of QA coordinator/designee | Organization-wide commitment and involvement |

The term quality assurance might still be used by individuals as a “trailing remnant of earlier days,” but it does not accurately convey the intent of the current quality management paradigm. Quality cannot be ensured; it can only be assessed, managed, or improved.

QUALITY ASSESSMENT AND IMPROVEMENT

Changing from quality “assurance” to quality “improvement” was much more than a renaming of a hospital or home care department. It was a major paradigm shift in health care culture. Through the continued work of the Institute of Medicine and the creation of private and governmental work groups focused on changing quality management processes, the health care system has survived the paradigm shift. Although much more work needs to be done, it is commonly accepted among providers that organizations must always strive to improve quality in order for health care facilities to survive and thrive. The antiquated cliché of “If it ain’t broke don’t fix it” is rarely heard in health care today. Instead, what is heard is, “If it ain’t broke, let’s see how we can make sure it never breaks.” To do so, the two steps of quality assessment and improvement methods must be used.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment is the first component of the two-step concept. It consists of data collection and data analysis. Quality assessment can be a highly complex process. It requires extensive planning and expertise to develop a successful quality assessment process. Many facilities hire professionals certified in health care quality as internal staff or as consultants to help design an assessment program. As discussed earlier in the chapter, because patient care is multifaceted, and because “quality” can be a very subjective term, quality assessment is challenging.

As nurses, there is an understanding of assessment; it is a basic component of the nursing process. Assessment requires observation and measurement of a problem or condition, and in quality assessment, the quality of care is observed and measured.

Imagine that the PICC program quality committee meets to discuss quality assessment. The question of whether or not absence of postinsertion phlebitis is a sign of a “quality” procedure is debated. Some felt it reflects more than just the performance of the team. It could be impacted by actions taken by the home care nurse or the medical unit staff. Patients with certain co-morbidities might be predisposed to phlebitis. After extensive debate, the group agreed to collect data on phlebitis. Discussion then ensued on which definition of phlebitis to use, and what severity or phlebitis rating would be considered a “defect” and counted. Further discussion (argument) ensued on what the appropriate time frame was for monitoring the site for phlebitis, and what to do if the patient had already been discharged to home. Ultimately, the team, with the help of the hospital’s QI director, develops the phlebitis data collection including the procedure, sample size, rating scale, paper logs, and desired graphics display.

Quality improvement

Quality improvement is the process necessary to initiate corrective actions or seize opportunities to improve the effectiveness and efficacy of services through the ongoing monitoring and assessment of a performance measure. It is the second step of the QA/QI model. It is the step (or phase) during which action steps are planned and performed. A critical point is that improvement cannot occur without valid and reliable assessment. “One cannot manage what one cannot measure” is a common phrase used by quality managers. It is not appropriate for a quality committee or team to embark on an improvement study based on anecdotal stories or situations. In order for true improvement and quality management to occur, the level of quality must be assessed first. Once assessment has been completed, improvement can take place.

Imagine that the PICC program studies postinsertion mechanical phlebitis rates. Based on a 100% sample size monitored 48 hours postinsertion, the phlebitis rate was 24 PICCs out of 280 PICCs inserted, or 8.6%. The industry benchmark found in the literature was 8.3%. (This is not an evidence-based statistic. Rather, it is a hypothetical statistic used for the purposes of this example.) The PICC team asks the QI director if a problem exists based on the data. By using statistical techniques, the QI director informs them that their slightly higher percentage is not statistically significant. In other words, they are within acceptable limits if only comparing to the benchmark.

However, the PICC team asks itself what it could do to lower the phlebitis rate the following month. Ideas are shared, strategies are planned and implemented, and over the course of the next 14 days changes are made in the postinsertion procedures. The only step remaining is to assess whether the steps taken lowered the phlebitis rate (improvement). To do so, the team used the same data collection study, and found the phlebitis rate decreased to 7.8%.

CONTINUOUS QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

We have described quality assessment and quality improvement (QA/QI), but what is “ continuous quality improvement” (CQI)? CQI builds on the foundation of QA/QI. CQI broadens the focus from only the clinical aspects of care to all the facets of the organization that affect patient outcomes. It sometimes requires a change in management philosophy and organizational culture, because there must be a visible commitment to CQI for the process to be effective. Current Joint Commission standards emphasize that managers and leaders in the organization contribute to the process by establishing expectations, providing necessary resources, and fostering communication and coordination of activities (TJC, 2008a).

The scope of CQI is more extensive than the activities of quality assessment and improvement. CQI considers processes by determining how well they are performed, coordinated, and integrated and by developing strategies for further improvement; it recognizes both internal customers (all employees) and external customers (patients, physicians, third-party payers) and values their perceptions of the care and services delivered; and it promotes the pursuit of objective data to evaluate and improve patient outcomes. In other words, CQI includes a broad organizational assessment of the total patient care experience.

An essential characteristic of CQI is that it is a continuous process. Quality is not achieved and then discarded; quality is the result of long-term commitment to the ongoing evaluation and improvement of patient outcomes. CQI is based on the assumption that outcomes are never optimized but may be constantly improved.

Another distinctive feature of CQI is that it emphasizes improvement in the interdisciplinary processes involved in patient care delivery, not just individual activities. Applying this concept to infusion nursing requires that all factors contributing to the quality of care be examined. An example is the administration of IV medication. Steps involved in this process in the hospital setting include receipt of a prescription for the medication by the physician, transcription of the order on the nursing unit, preparation and delivery of the medication by the pharmacy, and administration of the scheduled dose(s) by the nurse. Coordination of these various steps affects the quality of the desired outcome, which is efficient and effective administration of IV medication. Therefore with CQI, monitoring IV medication administration entails all functions contributing to the actual nursing procedure.

PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT

TJC continues to influence how organizations design and implement quality management programs. As a result, terminology and theoretical models recommended by TJC have significant impact, much like the ripples on a pond’s surface.

With the publication of their hospital and home care standards for 1999 and 2000, TJC introduced the term performance improvement. Its standards on quality referred to the “assessment and improvement of organizational performance” rather than on the assessment and improvement of quality.

Once again, the shift from “quality improvement” to “performance improvement” was not just another retitling of a hospital or home care company department. It was another shift in quality management philosophy. Although not as revolutionary as the shift from QA to QI, this shift focused on the difference between improving “quality” and improving “performance.” One must first differentiate between the two. Earlier in the chapter “quality” was defined, including a description of how “quality” is difficult to assess because it is highly subjective. On the other hand, “performance” is much more discreet. It is a specific aspect of the patient’s experience that can more clearly be defined, described, and measured.

Using the PICC team as an example, the overall “quality” of the program might be difficult to define and measure in a way that takes into consideration technical aspects as well as customer perceptions. However, the “performance” of the PICC team can be more easily measured. The number of PICCs inserted per day is measurable. The average wait time until insertion is measurable, and the incidence of infection per 1000 catheter days is measurable. One can see that performance, compared to quality, lends itself more easily to data collection and analysis.

The challenge facing hospitals and other providers of care is determining which discreet aspects of performance are most important. That is, which measurements of performance have the greatest ability to describe the overall patient care experience and which measurements have the ability to create the most positive improvements in patient care (Harrington and White, 2008)? Consensus groups continue to work diligently to determine what “core performance measures” should be collected and analyzed in every organization so that performance improvement can have the greatest impact.

Other than shifting the conceptual framework toward evaluating performance versus quality, the elements of assessment, analysis, improvement, and reassessment remain relatively unchanged from CQI. In addition, like CQI, performance improvement is leadership driven; crosses all key functional areas of an organization, including clinical, managerial, and support; and recognizes both internal and external customers.

TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT

With the shift from QA to CQI and now performance improvement (PI), health care organizations have recognized that quality is not a fixed commodity defined by health care professionals but is a strategic mission that must be shared by the entire organization. As a result, several health care organizations have adopted a management system that fosters continuous improvement at all levels and for all functions by focusing on maximizing customer satisfaction. This system is aptly named total quality management (TQM).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access