CHAPTER 28. Documentation

Brenda Dugger, MSHA, RN, CRNI®, CNA-BC

Historical Overview, 540

Purpose and Scope, 540

Documentation Guidelines, 541

Acute Care Documentation, 543

Home Care Documentation, 544

Non–Acute Nursing Facilities, 546

Infusion Therapy Documentation, 546

Communication, 548

Patient Teaching and Understanding, 548

Nursing Responsibilities, 548

Reimbursement, 549

Summary, 549

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

Documentation of the nursing process has always been viewed as a necessary but time-consuming chore. Over the past 20 years, nursing documentation has become more important and has changed to respond to the requirements of state and federal regulatory agencies, changes in nursing practice, determination of reimbursement fees, and legal ramifications.

Until around 3000 bc, when a system of writing was developed in Egypt, no formal records were kept by attendants to the sick. With the advent of Christianity, patient care records of nursing became organized and continuous. No one person contributed more to nursing than Florence Nightingale (1986). Documentation in 1820 to 1910 was used primarily to communicate the implementation of physicians’ orders. Nursing notes were not viewed as an important part of the patient’s medical record and were often discarded when the patient was discharged from the hospital.

In the 1930s a written plan of care was developed. In 1951 nursing standards became formalized, and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (now The Joint Commission) was formed. In the mid-1960s documentation in nurses’ notes evolved as an essential method of evaluating nursing care that met the requirements of regulatory agencies, provided evidence in litigation, and delineated professional responsibility. When diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) were implemented in the early 1980s, documentation in the medical record served as a mechanism for determining reimbursement guidelines. In the 1990s the emphasis was on quality improvement, with a focus on evaluating organizational and clinical performance outcomes. In the 2000s documentation emphasizes outcomes. It is important to emphasize activities that improve clinical performance and facilitate the continuous collection and evaluation of statistical data to improve care. Quality and outcomes will be tied to reimbursement. Publicly reported data will be available and health care providers and consumers will expect cost-effective positive outcomes. Documentation plays a key role in providing the information necessary to track and evaluate quality and patient care outcomes.

Electronic documentation offers many benefits to health care providers for data retrieval, avoidance of duplicate documentation, and analysis of care, interventions, and outcomes. Documentation systems should be designed in consultation with the nursing staff and their concerns should be addressed before the system is implemented. Entry and retrieval processes should be user friendly and help nurses think more critically to improve patient outcomes. This information would include the nursing-sensitive indicators such as patient falls, pressure ulcers, staff mix, nursing hours per patient day, job satisfaction, and nurse education (Monarch, 2007).

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) made additional recommendations in 2003 that all clinicians gain competency in delivering patient-centered care, working in interdisciplinary teams, practicing evidence-based medicine, focusing on quality improvement, and in using information technology (Chiverton and Witzel, 2008). They cited the need to expand use of bedside clinical testing technologies, electronic medical records, personal health records, and telehealth programs for which improved skills of documentation are imperative.

PURPOSE AND SCOPE

Documentation in the medical record is the best evidence that appropriate care was done and that the care was reasonable under the circumstances. Standards of care are based on the skill, care, and judgment used by an average health care provider under similar situations (Ferrell, 2007). Standards of care are determined by practice acts, state and federal regulatory agencies, The Joint Commission, organizational policies, and specialty organizations. Documentation validates that these standards are followed and assists with continuity of care among the health care team.

The Infusion Nursing Standards of Practice, published by the Infusion Nurses Society (2006), states that nursing documentation shall contain complete information regarding infusion therapy and vascular access in the patient’s permanent medical record. Specific documentation is required by state statutes and regulatory agencies and must include the documentation of invasive procedures such as infusion therapy. The underlying reason for these regulations is to protect the health care consumer by delineating professional responsibility and accountability. Nurses are responsible for assessment of the patient, development of the nursing plan of care to reach established goals, and evaluation of the effectiveness of the care given. This process along with determination of best practices to achieve quality outcomes constitutes evidence-based practice.

Nurses are responsible for data collection and for the documentation process. A coherent record of the patient care event or encounter should be evident through the medical record. Objective assessments use the nurses’ senses of sight, touch, hearing, and smell (Austin, 2006). Documentation provides the pathway to continuity of care. Each specialty or point of service reveals a part of the patient’s clinical picture or story. Documentation should clearly include the following:

• Diagnosis

• Assessment of the patient’s condition

• Care given to the patient

• Any unusual circumstances or complications

• Interventions performed to correct the situation

• Interactions with the physician, supervisor, or other health care professionals

• Evaluation of all interventions

• Outcomes

The necessity of effective documentation is an integral part of prudent patient care. The medical record is proof of the nursing process and the steps used to reach the resulting outcomes. Studies have shown that nurses often spend up to 30% of their time in the documentation process (Ferrell, 2007). As nursing responsibilities expand, professional roles and accountability increase. With this expanded role, critical thinking becomes essential to improve positive patient outcomes (INS, 2006). Hospital nurses often work by protocol to treat certain symptoms. For example, a protocol may direct the nurse to titrate a medication to obtain a certain effect. Home health nurses may work according to specific physicians’ orders, such as medication dosage ranges. While working alone in the community, home health nurses must make independent decisions about the patient’s condition and determine when a change in condition merits physician notification. Infusion nurses are called on to lead other health care professionals in recommending catheter selection or improving catheter function. These activities are orchestrated by good communication and should be evidenced throughout the documentation.

No longer are episodes of illness viewed as separate. A focus on wellness chooses to look at the life of the individual in its entirety and all of the influences that affect the health of the individual. Comprehensive documentation of care in all settings provides invaluable information to guide future treatment.

DOCUMENTATION GUIDELINES

Documentation should contain only factual information pertaining to the patient’s condition, diagnosis, and treatment. Speculation, conjecture, or demeaning comments are inappropriate and may be damaging to the patient, nurse, and the organization. Charting should never cover up an incident or document care that was not given. Inappropriate bias should be avoided, such as describing a patient as obnoxious, belligerent, hostile, or rude. Personal opinions should not be referenced. The medical record is confidential and is protected by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Access to this documentation should be monitored and controlled according to organizational policy.

WRITTEN DOCUMENTATION

Written documentation in the medical record should be legible and concise. Illegible writing may become the focal point for a plaintiff’s attorney, even if a mistake or error was not made. Scribbling, writing over another word or statement, and erasing an incorrect entry are unacceptable practices that can lead to disciplinary action in some organizations. In addition, writing over another word or statement or erasing an incorrect entry admits fault and can lead to serious consequences if the case is litigated. Errors should be corrected by drawing a line through the incorrect word or words and writing “error” or “mistaken entry” (Austin, 2006). The entry should be accompanied by the initials of the individual making the entry.

Common terminology, approved by the organization and written into policy, defines the accepted terms and clarifies misconceptions about meanings or interpretations. Abbreviations should be used only if accepted as the standard for the organization. The Joint Commission (2007c) has a Do Not Use list of abbreviations that should never be used because of their potential for confusion or misinterpretation (Table 28-1).

| Write out | Avoid |

|---|---|

| Unit, International Unit | Using U or IU |

| Daily, every other day | Q.D., QD, qd, Q.O.D., QOD, q.o.d., qod |

| Write X mg or 0.X mg | X.0 mg, .X mg |

| Morphine sulfate, magnesium sulfate | MS, MSO 4, MgSO 4 |

All observations should be recorded accurately. The date and the organization’s accepted method of keeping time (military or regular) should be used for every entry. Liability cases have used the documented time of treatment to determine the appropriateness of nurse response time and judgment relative to patient care.

The propensity for accurate documentation often arises from fear of litigation. Charting should always be written with potential legal review in mind. Investigation, deposition, and testimony often occur months or several years after the questionable event. Failure to appropriately document nursing assessment, interventions, or outcomes may cast doubt on the nurse’s actions. Comprehensive documentation often shows that the nurse is competent and cognizant of good nursing practice.

Documentation may be the difference in accusation of negligence or malpractice. The Joint Commission (2007d) defines negligence as “failure to use such care as a reasonably prudent and careful person would use under similar circumstances,” and malpractice as “improper or unethical conduct to unreasonable lack of skill by a holder of a professional or official position” (Box 28-1).

Box 28-1

DOCUMENTATION ISSUES THAT RISK PROFESSIONAL NEGLIGENCE CLAIMS

• Lack of informed consent, treatment, patient teaching, or discharge instructions

• Delays, substandard or inappropriate treatment

• Charting inconsistencies, late entries, improper alterations of the record

• Reference to an unusual occurrence report, conflicting documentation

• Missing records or destruction of records

A signature is mandatory after every entry. Chart reviews are difficult when entry ownership is not established or difficult to read. Initials are acceptable if the complete signature is on the bottom of the page or at the end of the documentation segment.

Flow sheets are often used for IV therapy records. They offer a concise list of IV fluids and medications given and the dates and time of IV catheter insertion and site checks. The flow sheet should include the type, length, gauge, removal, replacement, or rotation of the vascular access device. Degrees of phlebitis should be documented within the medical record each time a device is removed because of phlebitis. The degree of infiltration should also be documented in the medical record each time a device is removed when an infiltration has occurred. Considering the potency and venous irritability of many medications, charting observations about a discontinued device may help identify a postinfusion phlebitis.

COMPUTERIZED DOCUMENTATION

Most organizations are moving to electronic systems because of legibility and the ease of storage and retrieval of information. Along with enormous initial investment costs, concerns about moving to computerized documentation systems include fears that rapidly changing technology will make the system obsolete after only a few years. These systems are continually improved for easier user access, such as touch screens, handwriting interpretation, bar coding, and voice recognition.

Other considerations include the extensive hours required to build the screens and dictionaries, the variability of employee computer expertise, the reluctance of staff and physicians to learn the system, the amount of education and training needed for staff, and the maintenance of the system to meet changing regulatory requirements, new medications, or terminology changes. The availability of information is improved and easily attainable from episode to episode, whether inpatient or outpatient, to improve care through the continuum. When the patient’s entire clinical history is available, treatment can be more effective. Past illnesses may show trends and help reveal patterns of positive or negative outcomes from different courses of treatment. Online nursing documentation potentially improves overall documentation requirements because of the ability to halt screen progression until missing mandatory information is included (Langowski, 2005). Point of care technology keeps documentation data near the patient yet accessible by multiple parties in different locations at the same time. Opportunity for errors can be reduced and reduction of data entry can be accomplished (Box 28-2). Ease of implementation and the success of a computerized system are dependent upon the acceptance by the physicians and clinicians. It is essential that they understand the benefits for them, their organization, and their patients (Geibert, 2006).

Box 28-2

BENEFITS OF AN ELECTRONIC MEDICAL RECORD (EMR)

• Instant access to patient data

• Secure information

• Multiple end users

• Smooth flow inside and outside of hospital

• Data retrieval through report writing

• Reduction of medical errors

• Reduction of paperwork

From Doyle M: Promoting standardized nursing language using an electronic medical record system, AORN 83(6):1336, 2006; Wolf DM et al: Community hospital successfully implements eRecord and CPOE, Comput Inform Nurs 24(6):307-316, 2006.

The nurse’s signature is attached to the record by an individual password that the nurse uses to gain access to the system. The password should never be shared or used by anyone other than the person to whom it is assigned. Passwords should be changed often to prevent misuse and protect the system. Confidentiality must be emphasized so that the information is not used in an illegal or inappropriate manner. Entrance to the medical record can usually be tracked and an unauthorized chart entry may result in disciplinary action.

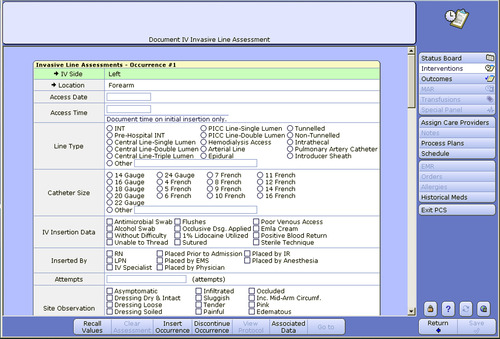

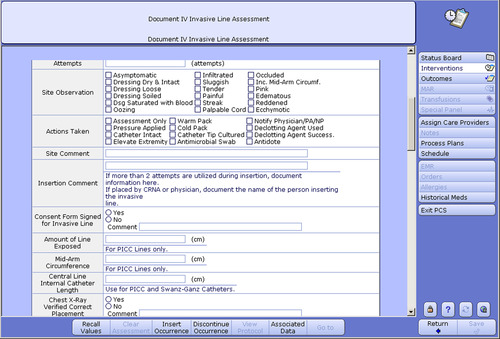

Using a computer is usually a simple process to document the selection of the insertion site and catheter gauge, purpose of therapy, degree of phlebitis or infiltration, and time of device removal (Figure 28-1). Such documentation can usually be accomplished by selecting the appropriate key words or phrases already programmed on the screen or by typing them onto the screen (Figure 28-2). The system should always allow options to add narrative notes to further explain or describe abnormal or unusual events or situations. Home care nurses may use handheld, tabletop, or laptop computers to document in the home setting. Although computerized records are more legible than handwriting, the format is not always clearly delineated, especially when the record is not printed in color. Computerized systems take time to master, but will be faster to use and accessed more quickly after several weeks of practice.

|

| FIGURE 28-1 Computerized charting IV invasive line assessment screen. (From Meditech PCS documentation system, St. Mary’s Health Care System, Athens, Ga.) |

|

| FIGURE 28-2 Computerized charting IV invasive line assessment screen. (From Meditech PCS documentation system, St. Mary’s Health Care System, Athens, Ga.) |

Some infusion pumps are computer-driven and have downloading capabilities that record information directly into the patient’s electronic health record. These systems have drug libraries that match the patient’s name, patient’s medical record number, physician’s order, drug name, drug dose, and nurse’s name to ensure verification of the right patient, the right drug, and the right dose.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access