Elaine Oden Kockrow and Barbara Lauritsen Christensen

Care of the surgical patient

Objectives

1. Identify the purposes of surgery.

2. Distinguish among elective, urgent, and emergency surgery.

3. Explain the concept of perioperative nursing.

4. Discuss the factors that influence an individual’s ability to tolerate surgery.

5. Discuss considerations for the older adult surgical patient.

6. Describe the preoperative checklist.

7. Explain the importance of informed consent for surgery.

9. Differentiate among general, regional, and local anesthesia.

10. Explain conscious sedation.

11. Describe the role of the circulating nurse and the scrub nurse during surgery.

13. Identify the rationale for nursing interventions designed to prevent postoperative complications.

14. List the assessment data for the surgical patient.

15. Identify the information needed for the postoperative patient in preparation for discharge.

16. Discuss the nursing process as it pertains to the surgical patient.

Key terms

ablation ( b-L

b-L -sh

-sh n, p. 18)

n, p. 18)

anesthesia ( n-

n- s-TH

s-TH -z

-z –

– , p. 37)

, p. 37)

atelectasis ( -t

-t -L

-L K-t

K-t -s

-s s, p. 49)

s, p. 49)

catabolism (k -T

-T B-

B- -l

-l sm, p. 52)

sm, p. 52)

conscious sedation (s -D

-D -sh

-sh n, p. 40)

n, p. 40)

evisceration ( -v

-v s-

s- r-

r- -sh

-sh n, p. 48)

n, p. 48)

incentive spirometry ( n-S

n-S N-t

N-t v sp

v sp -R

-R M-

M- -tr

-tr , p. 28)

, p. 28)

intraoperative ( n-tr

n-tr –

– P-

P- r-

r- -t

-t v, p. 18)

v, p. 18)

paralytic ileus (p r-

r- -L

-L T-

T- k

k  L-

L- –

– s, p. 52)

s, p. 52)

perioperative (p r-

r- –

– P-

P- r-

r- -t

-t v, p. 18)

v, p. 18)

postoperative (p st-

st- P-

P- r-

r- -t

-t v, p. 18)

v, p. 18)

preoperative (pr –

– P-

P- r-

r- -t

-t v, p. 18)

v, p. 18)

prosthesis (pr s-TH

s-TH -s

-s s, p. 41)

s, p. 41)

singultus (S NG-g

NG-g l-t

l-t s, p. 52)

s, p. 52)

surgical asepsis ( -S

-S P-s

P-s s, p. 44)

s, p. 44)

Surgery is defined as that branch of medicine concerned with diseases and trauma requiring operative procedures. Surgery became a medical specialty in the mid-nineteenth century. It enabled physicians to treat conditions that were difficult or impossible to manage only with medicine. However, early surgeons had little knowledge of the principles of asepsis, and anesthetic techniques were primitive and unsafe. Indeed, a surgeon’s success was based on speed. In the 1840s the discovery of anesthesia allowed surgeons to operate on a patient who was pain free. Nurses working in the first operating rooms (ORs) cleaned the rooms and equipment, performed technical tasks such as obtaining supplies, and occasionally accompanied the patient to the surgical ward to deliver nursing care.

With the advent of antiseptic and later aseptic practices, surgery became a treatment of choice for many conditions. Safer anesthetic gases allowed surgeons to conduct longer operative procedures. All surgery was conducted in hospital settings. Although modern-day suites have moved surgery from the Dark Ages, patients still often view the surgical process as mysterious and frightening.

Surgery is classified as elective, urgent, or emergency. Elective surgery is not necessary to preserve life and may be performed at a time the patient chooses. Urgent surgery is required to keep additional health problems from occurring. Emergency surgery is performed immediately to save the individual’s life or preserve the function of a body part. Surgical procedures may also be labeled as either major or minor, although all surgeries have an element of risk.

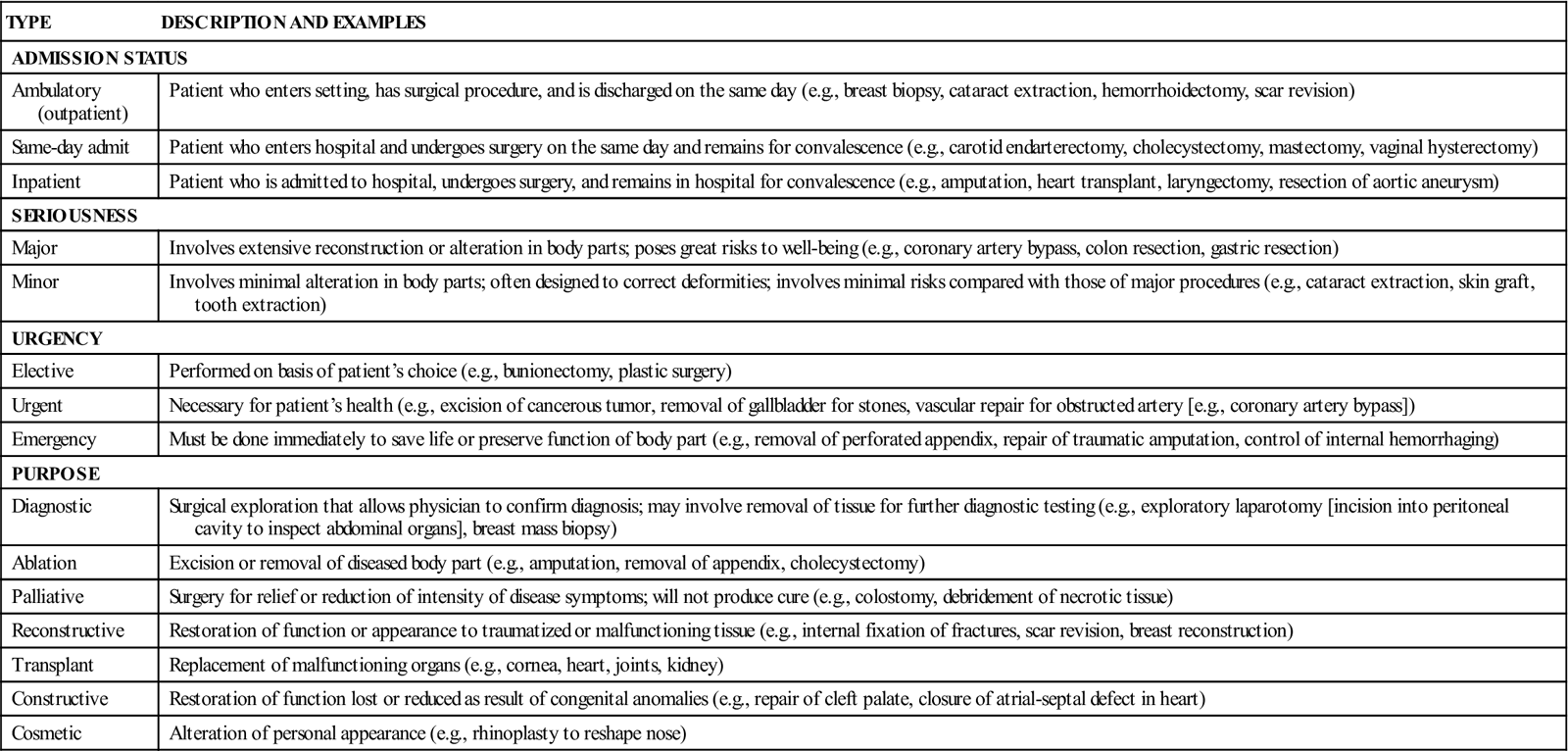

Surgery is performed for various purposes, including diagnostic, ablation (amputation or excision of any body part or removal of a growth or harmful substance), palliative (therapy to relieve or reduce uncomfortable symptoms without cure), reconstructive, transplant, constructive, and cosmetic (Table 2-1). See Table 2-2 for frequently used surgical terminology.

Table 2-1

Classification for Surgical Procedures

| TYPE | DESCRIPTION AND EXAMPLES |

| ADMISSION STATUS | |

| Ambulatory (outpatient) | Patient who enters setting, has surgical procedure, and is discharged on the same day (e.g., breast biopsy, cataract extraction, hemorrhoidectomy, scar revision) |

| Same-day admit | Patient who enters hospital and undergoes surgery on the same day and remains for convalescence (e.g., carotid endarterectomy, cholecystectomy, mastectomy, vaginal hysterectomy) |

| Inpatient | Patient who is admitted to hospital, undergoes surgery, and remains in hospital for convalescence (e.g., amputation, heart transplant, laryngectomy, resection of aortic aneurysm) |

| SERIOUSNESS | |

| Major | Involves extensive reconstruction or alteration in body parts; poses great risks to well-being (e.g., coronary artery bypass, colon resection, gastric resection) |

| Minor | Involves minimal alteration in body parts; often designed to correct deformities; involves minimal risks compared with those of major procedures (e.g., cataract extraction, skin graft, tooth extraction) |

| URGENCY | |

| Elective | Performed on basis of patient’s choice (e.g., bunionectomy, plastic surgery) |

| Urgent | Necessary for patient’s health (e.g., excision of cancerous tumor, removal of gallbladder for stones, vascular repair for obstructed artery [e.g., coronary artery bypass]) |

| Emergency | Must be done immediately to save life or preserve function of body part (e.g., removal of perforated appendix, repair of traumatic amputation, control of internal hemorrhaging) |

| PURPOSE | |

| Diagnostic | Surgical exploration that allows physician to confirm diagnosis; may involve removal of tissue for further diagnostic testing (e.g., exploratory laparotomy [incision into peritoneal cavity to inspect abdominal organs], breast mass biopsy) |

| Ablation | Excision or removal of diseased body part (e.g., amputation, removal of appendix, cholecystectomy) |

| Palliative | Surgery for relief or reduction of intensity of disease symptoms; will not produce cure (e.g., colostomy, debridement of necrotic tissue) |

| Reconstructive | Restoration of function or appearance to traumatized or malfunctioning tissue (e.g., internal fixation of fractures, scar revision, breast reconstruction) |

| Transplant | Replacement of malfunctioning organs (e.g., cornea, heart, joints, kidney) |

| Constructive | Restoration of function lost or reduced as result of congenital anomalies (e.g., repair of cleft palate, closure of atrial-septal defect in heart) |

| Cosmetic | Alteration of personal appearance (e.g., rhinoplasty to reshape nose) |

Table 2-2

| TERM | INTERPRETATION WITH EXAMPLE |

| Anastomosis | Surgical joining of two ducts or blood vessels to allow flow from one to another; to bypass an area (e.g., Billroth I, joins stomach and duodenum) |

| -ectomy | Surgical removal of (e.g., cholecystectomy, removal of the gallbladder) |

| Lysis | Destruction or dissolution of (e.g., lysis of adhesions, removal of adhesions) |

| -orrhaphy | Surgical repair of (e.g., herniorrhaphy, repair of a hernia) |

| -oscopy | Direct visualization by a scope (e.g., cystoscopy, direct visualization of the urinary tract by means of a cystoscope) |

| -ostomy | Opening made to allow the passage of drainage (e.g., ileostomy, formation of an opening of the ileum onto the surface of the abdomen for passage of feces) |

| -otomy | Opening into (e.g., thoracotomy, surgical opening into the thoracic cavity) |

| -pexy | Fixation of (e.g., cecopexy, fixation or suspension of the cecum to correct its excessive mobility) |

| -plasty | Plastic surgery (e.g., mammoplasty, reshaping of the breasts to reduce, lift, reconstruct) |

Traditionally, surgical procedures were performed in hospitals. With the discovery of new technologies and today’s emphasis on decreasing health care costs, the surgical suite may now be in a variety of settings. Although facilities use different terms for surgical settings and processes, some common variations exist (Box 2-1).

Perioperative nursing

Perioperative nursing refers to the nurse’s role during the preoperative (before surgery), intraoperative (during surgery), and postoperative (after surgery) phases of a surgical experience. Perioperative nursing stresses the importance of providing continuity of care for the surgical patient using the nursing process. In many hospitals, perioperative nurses assess a patient’s health status preoperatively, identify specific patient needs, teach and counsel, attend to the patient’s needs in the OR, and then follow the patient’s recovery. However, in other institutions, different nurses care for the patient during each phase. Nurses also may delegate certain aspects of perioperative nursing to appropriate personnel (Box 2-2). The nurse’s major responsibility is safe, consistent, and effective nursing interventions during each phase of surgery.

Influencing factors

Regardless of the surgical procedure, the process is stressful for the patient. Observing a patient’s mannerisms and listening to questions help identify the patient’s feelings and concerns. By helping patients express their concerns, the nurse can offer support, reassurance, and information—the best way to address fear of the unknown.

Numerous factors affect the individual’s ability to tolerate surgery.

Age

The young and the old do not tolerate major surgical treatment as well as those in other age-groups. Their altered metabolic needs may not respond to physiologic changes quickly. Specific concerns center on the body’s response to temperature changes, cardiovascular shifts, respiratory needs, and renal function. To assist patients in returning to their optimal level of health, nursing assessments and appropriate interventions should be ongoing (see Life Span Considerations box).

Physical condition

Healthy patients have smoother and faster recovery periods than patients who have coexisting health problems. Assess each body system to identify actual and potential problems, then select measures to prevent postsurgical complications (Box 2-3).

Nutritional factors

The body uses carbohydrates, proteins, and fats to supply energy-producing glucose to its cells. Carbohydrates and fats are the primary energy producers, and protein is essential to build and repair body tissue. During stressful conditions, the body’s need for energy and repair increases. Nutritional needs are affected by a patient’s age and physical requirements; patients who maintain a sound, nutritional diet tend to recover more quickly.

A complete diet history identifies the patient’s usual eating habits, nutritional patterns, and food preferences. Dietary practices are influenced by a patient’s ethnic, cultural, religious, and socioeconomic background. With this information, offer the patient appropriate foods that are high in energy-producing nutrients. Surgery may decrease a patient’s appetite and alter metabolic functions, so observe the patient for signs of malnutrition. If malnutrition is promptly identified, tube feedings, intravenous (IV) therapy, or parenteral hyperalimentation can be initiated (see Chapter 21 in Foundations of Nursing).

Psychosocial needs

As patients and families plan for surgery, they frequently express concern and fears about possible outcomes (Box 2-4). Preoperative fear has been linked to postoperative behavior. The preoperative anxiety level influences the amount of anesthesia required, the amount of postoperative pain medication needed, and the speed of recovery from surgery. Determine each patient’s perceptions, emotions, behavior, and support systems that may help or hinder their progress through the surgical period. Patiently and actively listening to the patient, the family, and significant others invites confidence and helps reduce anxiety levels (Figure 2-1).

While the patient attempts to understand the approaching surgery, family members and support people are also trying to cope. Families may have additional burdens, such as financial obligations, living changes, and added personal responsibilities. In addition to nursing and medical personnel, ministerial staff, social workers, or patient advocates can provide support for patients and families during this stressful time (see Patient Teaching box).

Socioeconomic and cultural needs

The United States is a nation of diverse individuals from different social, economic, religious, ethnic, and cultural origins. Even geographic location affects the way a patient responds to surgery. Therefore it is important to allow patients and families to express themselves openly.

Patients from different cultures (see Chapter 8 in Foundations of Nursing) may react to the preoperative experience in different ways. A multicultural perspective helps nurses approach patients with respect and individually tailor care that promotes recovery (see Cultural Considerations box).

Medications

Review of the patient’s current medication regimen is essential. Polypharmacy (concurrent use of multiple medications) occurs in all age-groups but is more common with older adults. Studies have shown that patients age 65 and older use an average of two to six prescribed medications and one to three over-the-counter medications. The use of multiple medications can lead to adverse drug reactions and interactions with other medications in the perioperative setting.

During the surgical experience, health care providers use medications in a number of pharmacologic categories, including anesthesia agents, antimicrobials, anticoagulants, hemostatic agents, oxytocics, steroids, diagnostic imaging dyes, diuretics, central nervous system agents, and emergency protocol medications. A seriously ill patient may receive as many as 20 medications in a perioperative setting at one time. Large numbers of medications increase the chance of interactions.

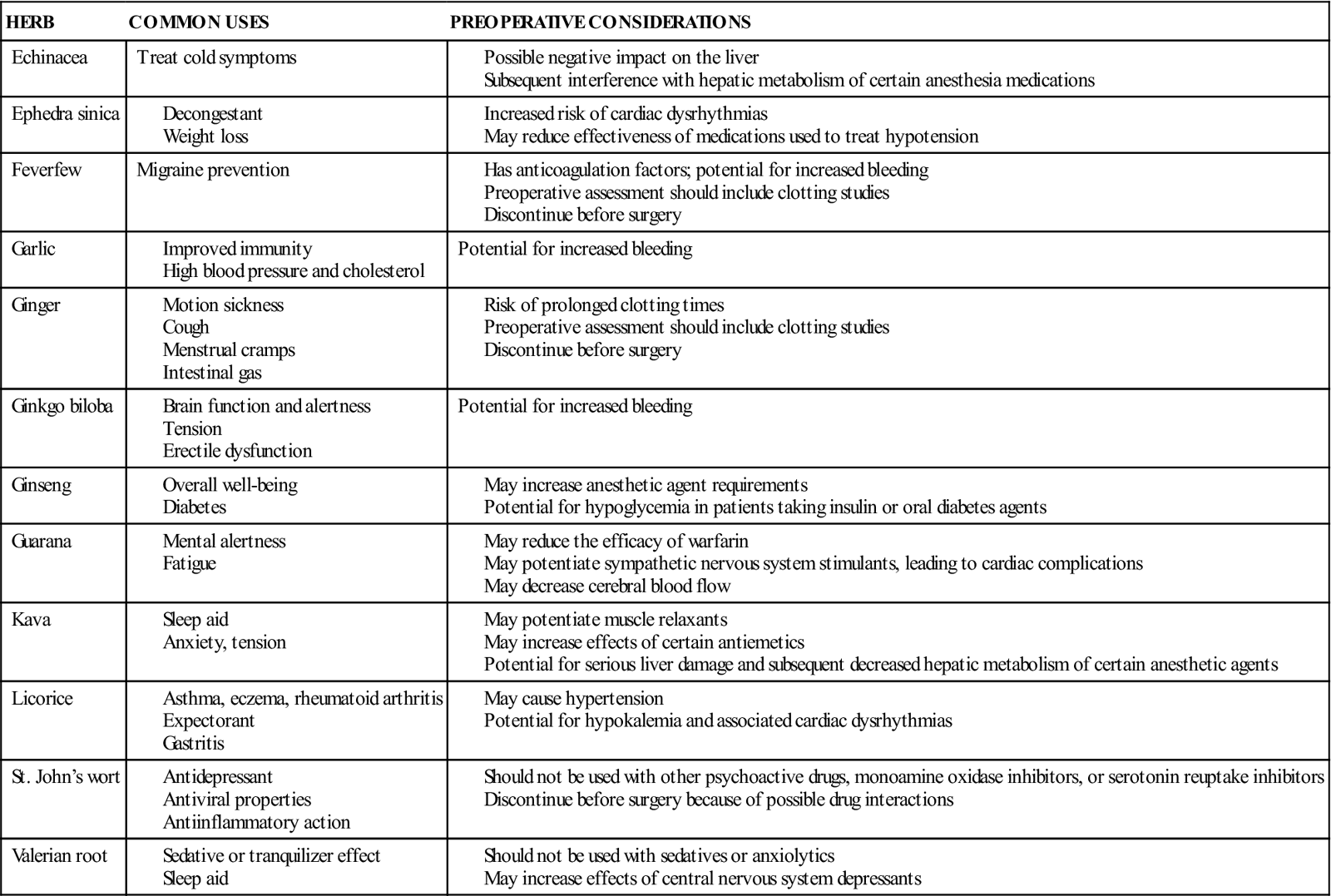

Patients also frequently use herbal remedies as alternative or complementary medicines. Ask patients about their use of herbal remedies, either as dietary supplements or as medicines. Unless specifically asked, some patients may not consider their natural remedies as medicines. Even though herbs are natural products, they act like medications and may interact with or potentiate other medications or interfere with surgical procedures (Table 2-3).

Table 2-3

Preoperative Considerations for Commonly Ingested Herbs

Some medications may be stopped when a patient goes to surgery. However, it is important to know the purposes and actions of drugs, since they may be critical for patients with diseases such as diabetes. The anesthesiologist, in collaboration with the patient’s physician and surgeon, determines whether these medications should be taken the day of surgery and postoperatively.

Remember to assess for allergies to drugs that may be given during any phase of the surgery. If patients say they are allergic to a drug, ask them exactly what happened when they took it. Also ask about nondrug allergies, including allergies to foods, chemicals, pollen, antiseptics used to prepare the skin for surgery, and latex rubber products. Patients with a history of allergic responsiveness are more likely to have hypersensitivity reactions to anesthesia agents. Many facilities require such patients to wear an allergy identification band during surgery. Flag the front of the patient’s chart to alert all health care providers to the allergy status.

Education and experience

As individuals age, life experiences influence problem-solving abilities and coping methods. Tailoring information to a patient’s educational level enables understanding to replace fear. Encourage patients to repeat or summarize what has been presented. This process double checks what patients heard and how they interpreted it.

Preoperative phase

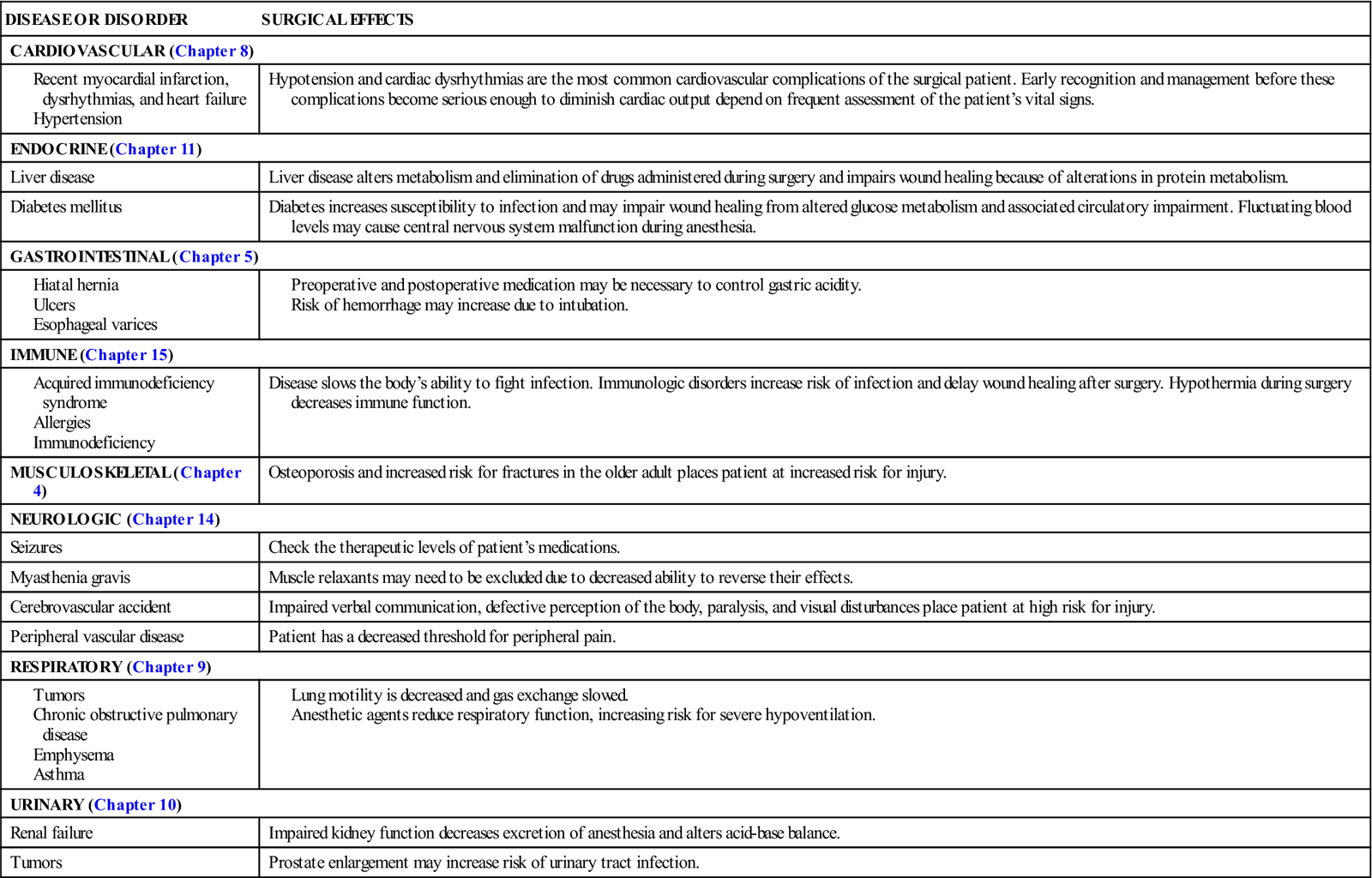

Before surgery, patients require a thorough health assessment. Acute or chronic diseases hinder the body’s ability to repair itself or adjust to surgical treatment. Disorders of the systems identified in Table 2-4 present high-risk conditions for surgery. Each system is further affected by the patient’s age, health, nutritional status, and mental state. Assessment questions regarding the patient’s use of chemicals, alcohol, and recreational substances help the health team select medications. Postoperative care is also adjusted, when possible, to prevent potential complications. For example, a patient who smokes cigarettes may have impaired alveoli and reduced lung capacity. Mucus and anesthesia by-products may be trapped in the lung, causing atelectasis and pneumonia. After surgery, breathing exercises and treatments for the smoker aid in lung expansion and decrease the risk of respiratory complications.

Table 2-4

Surgical Effects on Body Systems

| DISEASE OR DISORDER | SURGICAL EFFECTS |

| CARDIOVASCULAR (Chapter 8) | |

| Hypotension and cardiac dysrhythmias are the most common cardiovascular complications of the surgical patient. Early recognition and management before these complications become serious enough to diminish cardiac output depend on frequent assessment of the patient’s vital signs. | |

| ENDOCRINE (Chapter 11) | |

| Liver disease | Liver disease alters metabolism and elimination of drugs administered during surgery and impairs wound healing because of alterations in protein metabolism. |

| Diabetes mellitus | Diabetes increases susceptibility to infection and may impair wound healing from altered glucose metabolism and associated circulatory impairment. Fluctuating blood levels may cause central nervous system malfunction during anesthesia. |

| GASTROINTESTINAL (Chapter 5) | |

| IMMUNE (Chapter 15) | |

| Disease slows the body’s ability to fight infection. Immunologic disorders increase risk of infection and delay wound healing after surgery. Hypothermia during surgery decreases immune function. | |

| MUSCULOSKELETAL (Chapter 4) | Osteoporosis and increased risk for fractures in the older adult places patient at increased risk for injury. |

| NEUROLOGIC (Chapter 14) | |

| Seizures | Check the therapeutic levels of patient’s medications. |

| Myasthenia gravis | Muscle relaxants may need to be excluded due to decreased ability to reverse their effects. |

| Cerebrovascular accident | Impaired verbal communication, defective perception of the body, paralysis, and visual disturbances place patient at high risk for injury. |

| Peripheral vascular disease | Patient has a decreased threshold for peripheral pain. |

| RESPIRATORY (Chapter 9) | |

| URINARY (Chapter 10) | |

| Renal failure | Impaired kidney function decreases excretion of anesthesia and alters acid-base balance. |

| Tumors | Prostate enlargement may increase risk of urinary tract infection. |

Additional preoperative questions identify allergies, past surgeries, and infection and disease history. Ask the patient to name prescription drugs currently taken, over-the-counter drugs, and home remedies. Also record the patient’s vital signs, height, and weight before surgery to have a baseline for postoperative comparison.

Preoperative teaching

Patient teaching before surgery helps decrease the patient’s stress associated with fear of the unknown. Preoperative information helps reduce (1) anxiety, (2) the amount of anesthesia needed, (3) postsurgical pain, and (4) corticosteroid production. Decreasing postsurgical complications through preoperative teaching speeds wound healing.

In providing preoperative teaching, include the patient and family and remember that basic terminology and information are easier to understand than complex explanations. Stop frequently to verify the patient’s understanding of information, ask questions, and encourage responses. Avoid questions that can be answered “yes” or “no.” For example, “Do you have any questions?” is not as good as “What questions do you have?” If printed materials or videotapes are routinely used in preoperative teaching sessions, document what the patient read, heard, or saw. Older adults may have difficulty reading small print or hearing taped messages. If the patient does not understand English, an interpreter can explain information presented. Also emphasize that a nurse will be with the patient throughout the entire surgical experience.

For surgical procedures that have potential long-term effects, support groups can offer support preoperatively. Cancer organizations, amputation support groups, and enterostomal therapist associations are examples of large national organizations that offer peer support for surgical and nonsurgical patients.

Ideally, preoperative teaching is provided 1 or 2 days before surgery, when anxiety is not as high. In some instances, the patient may not be admitted to the hospital until early on the day of surgery. Most institutions have an established teaching program, often with a systematic preoperative teaching plan and checklist. Begin by clarifying the sequence of preoperative and postoperative events. Generally, instruct the patient about the surgical procedure, informed consent, the method of skin preparation, and the gastrointestinal (GI) cleanser to be used. Clarify what the physician has explained. Review the time of the surgery and information about the recovery area (e.g., previously assigned units, intensive care, specialty units, or outpatient area). If a transfer is planned, it is helpful to take the patient and family on a tour of the new unit. Reinforce that vital signs, dressings, and tubes are assessed every 15 to 30 minutes until the patient is awake and stable.

Preoperative preparation

Preparation for surgery depends on the patient’s age and physical and nutritional status, the type of surgery, and the surgeon’s preference. For surgery in a short-stay or ambulatory setting, the workup normally occurs a few days in advance. If the patient is admitted to the hospital, testing may be conducted to assess for potential problems. Preparation frequently includes both in-hospital testing and evaluation of test results that were completed in the physician’s office.

Laboratory tests and diagnostic imaging

Testing before surgery depends on the institution’s policies, the physician’s directives, and the patient’s condition. Follow standing orders in completing this overall process. Laboratory tests commonly reviewed before surgery include a urinalysis; a complete blood count; and a blood chemistry profile to assess endocrine, hepatic, renal, and cardiovascular functions. Serum electrolytes are evaluated if extensive surgery is planned or the patient has associated problems. One essential electrolyte examined is potassium; if not enough potassium is available, dysrhythmias can occur during anesthesia and the patient’s recovery may be delayed by general muscle weakness. A chest x-ray evaluation and electrocardiogram are used to identify disease processes or existing respiratory or cardiac damage. Additional tests are conducted to assess the organ involved in surgery. Blood chemistry profile (lactate dehydrogenase, γ-glutamyltransferase, alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin) and urine bilirubin levels are used to assess hepatic function.

Informed consent

The Patient’s Bill of Rights affirms that patients must give informed consent (permission to perform a specific test or procedure) before the beginning of any procedure. In signing the consent form, the patient must be competent and agrees to have the procedure that is stated on the form. Information must be clear, the risks explained, expected benefits identified, and consequences or alternatives for the presenting problem stated. Witnesses are required to meet the state’s legal requirements. A witness only verifies that this is the person who signed the consent and that it was a voluntary consent. The witness (often a nurse) does not verify that the patient understands the procedure. Ideally, the surgeon discusses the surgical procedure with the patient in advance. In some institutions, the surgical consent is completed in the physician’s office or in the admissions department before the patient is admitted to the unit. Informed consent should not be obtained if the patient is disoriented, unconscious, mentally incompetent, or, in some agencies, under the influence of sedatives. Know agency policy (see Chapter 2, Figure 2-1 in Foundations of Nursing).

If the patient does not see or hear well, allow additional time to explain the surgery. For patients who do not understand English or are deaf, an interpreter may be necessary. Never coerce a patient into signing a consent that he or she does not understand or that contains information different from that originally given. If necessary, contact the physician and indicate that the patient does not understand the procedure.

In an emergency, the patient may not be able to give consent for surgery. Every effort is made to locate family members to assume this responsibility. Occasionally telephone permission may be obtained. Hospitals have standard guidelines for obtaining verbal consent. If the patient’s life is in danger and family members cannot be located, the surgeon may legally perform surgery. If family members object to surgery that the physician believes is essential, a court order may be obtained for the procedure. This practice is used only in extreme circumstances, however (e.g., when a child’s life is in danger). Know agency policy.

Gastrointestinal preparation

At midnight before surgery, the patient is usually placed on nothing by mouth (NPO) status; this ensures the GI tract is empty when the patient is anesthetized, thereby decreasing the chance of vomiting or aspirating emesis after surgery. An NPO sign is posted over the patient’s bed, and all fluids are removed from the room. Reinforce with both the patient and the family the importance of not ingesting foods or fluids. If the patient fails to comply with the NPO order, notify the physician. An order for NPO after midnight should apply to solid foods for patients scheduled for surgery in the morning. An early light breakfast is allowed for afternoon procedures. Clear liquid may be taken up to 3 hours before surgery.

Patients can have oral care while NPO, but caution them not to swallow fluids used. A wet cloth on the lips helps relieve dryness. If patients need to be hydrated or require special IV medications, the physician may order parenteral fluids or medication. Depending on the surgery, many patients resume foods and fluids the same day after surgery.

Because anesthesia relaxes the bowel, a bowel cleanser may be ordered to evacuate fecal material and lessen postoperative GI problems (nausea and vomiting). A cleansing enema or a general laxative is frequently used. A GI lavage solution, GoLYTELY (an isosmotic solution), rapidly evacuates the bowel. GoLYTELY is contraindicated, however, in patients with GI obstruction, gastric retention, bowel perforation, toxic colitis, or megacolon. If a bowel preparation is used, chart the type of preparation used, the patient’s tolerance to the procedure, and results. Before bowel surgery, medication (neomycin, sulfonamides, erythromycin) may be given over a period of days to detoxify and sterilize the GI tract. This lessens the chance of fecal contamination during surgery.

Skin preparation

Before surgery the patient may have hair removed at the surgical site. The operative site must be shaved carefully to remove the hair without injuring the skin (Skill 2-1). However, surgeons generally order hair removal only if it might interfere with exposure, closure, or dressing of the surgical site. Shaving the hair before surgery creates microscopic cuts that increase the risk of surgical site infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention strongly recommends not removing hair at all unless it would interfere with the surgery (Nichols, 2001).

There is debate about the best method to remove hair. A lower rate of infection occurs with either no shave or use of electric clippers than with any other method. Use of a depilatory agent (a substance or procedure that removes hair) also has a low wound infection rate. In some cases, the patient showers after hair removal, unless contraindicated, using an antiseptic soap such as Hibiclens. If the surgical procedure involves the head, neck, or upper chest area, the patient also shampoos the hair.

If shaving is used, it should be performed close to the actual time of the surgical procedure to decrease the time for growth of bacteria and lower the potential for infection. Some surgical departments prepare the patient either in a surgical holding room or in the OR itself. Each agency or facility should have policies and protocols regarding the timing, the method, and the people responsible for the preoperative skin preparation of surgical patients.

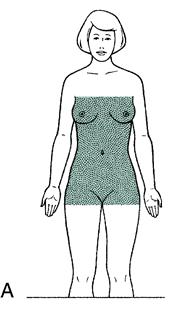

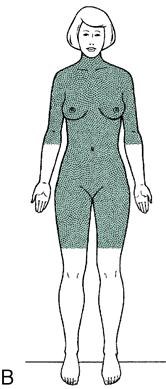

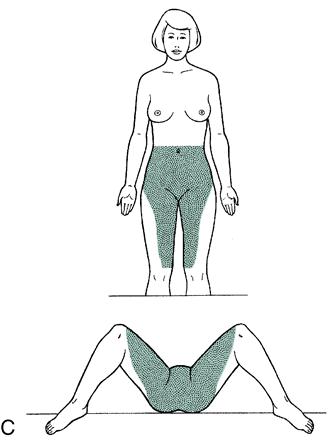

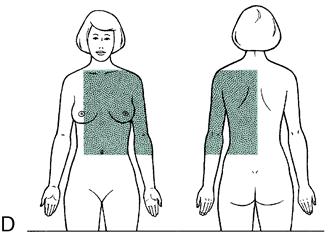

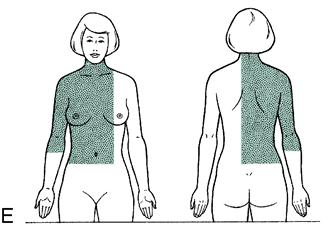

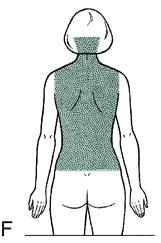

Hospital policies differ regarding the description of skin areas to be prepped, or the surgeon may give specific orders. Review agency policy and the patient chart to determine the area to be shaved (Figure 2-2). Before the skin preparation, carefully assess the surgical site for skin impairment (e.g., infection, irritation, bruises, or lesions). Assess the patient for allergies. Record anything unusual and report it to the surgeon.

Once the patient is in the OR, scrub the skin thoroughly with a detergent solution and then apply an antiseptic solution to kill more adherent and deeper-residing bacteria. The surgeon may place a transparent sterile drape directly over the skin before making an incision.

Special concerns for patients undergoing a surgical skin preparation are as follows:

• Small children may be easily frightened by this procedure, and it may need to be done in the OR.

• Older adults need a detailed explanation to relieve their anxiety.

Latex allergy considerations

Focused assessment of risk factors helps identify patients with the nursing diagnosis of risk for latex allergy response. Assessing the patient’s experience helps identify those at risk for a systemic reaction; for example, patients may relate stories of complicated anesthesia events, hives from blowing up a balloon, or severe swelling of the labia with a urinary catheterization.

With the advent of Universal Precautions (now called Standard Precautions) in the late 1980s, the use of latex gloves dramatically increased, and latex allergies became much more common. Basically, every health care worker wears gloves. Most gloves are powdered to make them easier to put on. The powder absorbs protein allergens from the latex and deposits them on skin and into surgical wounds; it also aerosolizes the protein allergens. Aerosolized latex allergens are carried in ventilation systems, requiring further preventive measures.

Latex allergy is classified in three categories: irritant reaction and types IV and I allergic reactions. The irritant reaction, which is most commonly seen, is actually a nonallergic reaction. The type IV allergic reaction to latex is a cell-mediated response to the chemical irritants found in latex products. The true latex allergy is the type I allergic reaction, and it occurs shortly after exposure to the proteins in latex rubber. The type I reaction is an immunoglobulin E–mediated systemic reaction that occurs when latex proteins are touched, inhaled, or ingested.

Factors influencing the risk for latex allergy response are the person’s susceptibility and the route, duration, and frequency of latex exposure. Risk factors include the following:

• History of anaphylactic reaction of unknown etiology during a medical or surgical procedure

• Multiple surgical procedures (especially from infancy)

• Food allergies (specifically kiwi, bananas, avocados, chestnuts)

• A job with daily exposure to latex (health care, food handlers, tire manufacturers)

• History of reactions to latex (balloons, condoms, gloves)

• Allergy to poinsettia plants

To provide a latex-safe environment for susceptible patients, all surgical patients should be screened for the risk for latex allergy response before admission. Identification of patients at risk is the first step in preventing a reaction.

When a patient with a suspected or known latex allergy is scheduled for surgery, all latex use is avoided and the patient is admitted directly to the OR as the first case of the day, if possible. Many facilities have converted isolation rooms into latex-safe environments for patients with latex allergy. Ensure that everyone on the health care team is aware that a patient is, or may be, latex allergic. Place a medical alert or allergy band around the patient’s wrist, and clearly flag the patient’s status on the chart. Remove all natural rubber latex products from the area. Use latex-free measures to prepare the patient’s medication. Have a crash cart standing by stocked with latex-free equipment, supplies, and drugs for treating anaphylaxis. As ordered, give preoperative prophylactic treatment with glucocorticoid steroids and antihistamines. Box 2-5 lists interventions for the perioperative care of patients with risk for latex allergy response.

Respiratory preparation

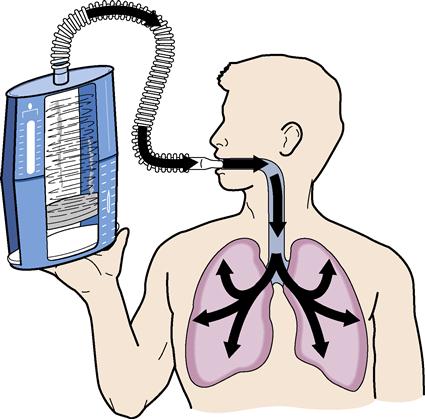

If a general anesthetic is administered, it is essential to ventilate the lungs postoperatively to prevent or treat atelectasis, improve lung expansion, improve oxygenation, and prevent postoperative pneumonia. Because the lungs do not expand fully during surgery, mucus and gases remain in the lungs until expelled. Pulmonary exercises can assist in expanding the lungs and removing these by-products. Preoperative introduction to the use of the incentive spirometer is of great value to the patient.

In spirometry, referred to as incentive spirometry, the patient uses a device (spirometer) at the bedside at regular intervals to promote deep breathing (Skill 2-2). The amount of air inspired is measured and the patient encouraged to attain the established goal. The respiratory therapist calculates the patient’s maximum inspiratory capacity based on height, age, and sex, taking into consideration the type of surgery performed. At rest, the usual tidal capacity is 500 mL of inspired air. In a tall, healthy young man, a tidal capacity of 4300 mL is not uncommon. Because of postoperative pain, a postoperative inspiratory capacity of one half to three fourths of the preoperative volume is acceptable.

-K

-K K-s

K-s –

– ,

,  -H

-H S-

S- ns,

ns,  M-b

M-b -l

-l s,

s,  ks-T-b

ks-T-b t,

t,  KS-

KS- -d

-d t,

t,  n-S

n-S ZH-

ZH- n,

n,  N-f

N-f hrkt,

hrkt,  L-

L- –

– -t

-t v,

v,  M-b

M-b s,

s,