Revenue cycle and financial management

Bryon D. Pickard

Objectives

• Use fiscal terms with understanding.

• Describe the various stages of the revenue cycle.

• List different reimbursement methodologies.

• Explain the differences between financial and managerial accounting.

• Calculate key financial ratios.

• Understand the difference between cash and revenue.

• Explain the role of the health information professional in the budgeting process.

• Recognize that organizational planning drives financial management activities.

• Prepare a business plan and a budget.

• Explain the purpose of each budget type.

• Use capital evaluation methods.

• Describe various cost allocation methods.

• Assist in charge master updates.

• Review and analyze variance reports.

• Define general principles of accounting.

• Review and apply ratios to financial reports.

Key words

Accounting rate of return

Accounts receivable

Accounts receivable turnover ratio

Accrual basis accounting

Action steps

Activity ratio

Assets

Balance sheet

Budgets

Business plan

Capital expenditure

Capital expenditure committee

Capitalization ratios

Capitation

Cash basis accounting

Certificate of need

Charge description master

Charge master

Chart of accounts

Compounding effect

Controlling

Current ratio

Days of revenue in patient accounts receivable ratio

Depreciation

Disclosure

Discounting

Double-distribution method

Entity

Equity

Fee schedule

Financial accountant

Financial accounting

Financial analysis

Flexible budget

Fund balance

Goals

Liabilities

Liquidity ratios

Long-term debt/total assets ratio

Managerial accountant

Managerial finance officer

Master budget

Master charge list

Matching concept

Medicare

Mission

Net

Net operating revenue

Net present value

Objectives

Objectivity

Operating budget

Operating margin ratio

Opportunity costs

Participating provider

Payback method

Per case

Per diem

Performance ratio

Productive time

Profit

Prospective payment system

Ratio analysis

Revenue

Rolling budget method

Simultaneous-equations method

Stable monetary unit

Statement of cash flow

Statement of revenues and expenses

Statistics budget

Step-down method

Third-party payer

Time value of money

Turnover ratio

Variance report

Whole service

Zero-based budget

Abbreviations

AHA—American Hospital Association

AICPA—American Institute of Certified Public Accountants

ANSI—American National Standards Institute

ARRA—American Recovery and Reinvestment Act

CCI—Correct Coding Initiative

CDM—Charge Description Master

CFO—Chief Financial Officer

CLIA—Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment

CMS—Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

COB—Coordination of Benefits

DRG—Diagnosis-Related Group

EDI—Electronic Data Interchange

EFT—Electronic Funds Transfer

EOB—Explanation of Benefits

ERA—Electronic Remittance Advice

FASB—Financial Standards Accounting Board

GAAP—Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

GASB—Government Accounting Standards Board

HCPCS—Health Care Procedure Coding System

HIM—Health Information Management

HIPAA—Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

HMO—Health Maintenance Organization

IRS—Internal Revenue Service

NCQA—National Committee for Quality Assurance

NPI—National Provider Identifier

PCAOB—Public Company Accounting Oversight Board

PHI—Personal Health Information

PPO—Preferred Provider Organization

PPS—Prospective Payment System

PQRI—Physician Quality Reporting Initiative

RAC—Recovery Audit Contractor

RBRVS—Resource-Based Relative Value Scale

RVU—Relative Value Unit

UB-04—Uniform Billing Code of 2004

Student Study Guide activities for this chapter are available on the Evolve Learning Resources site for this textbook. Please visit http://evolve.elsevier.com/Abdelhak.

When you see the Evolve logo  , go to the Evolve site and complete the corresponding activity, referenced by the page number in the text where the logo appears.

, go to the Evolve site and complete the corresponding activity, referenced by the page number in the text where the logo appears.

An explanation of why health information management (HIM) is of widespread interest is that the field itself is so broad. Health information professionals have long been considered experts and industry leaders when it comes to understanding health care information regulations, statutes, data standards, and clinical vocabularies and terminologies. The role of information management and documentation principles is essential to the successful application of technology and ensuring an effective health information infrastructure. It is the assurance of reliable standards, data integrity, and ethical principles and guidelines that makes health care information of use for organizations and individuals. Health information is utilized in clinical decision making, improving quality and safety, consumer empowerment, research, and fulfilling administrative and policy needs. In the same manner, financial management and accounting principles exist to ensure the quality, integrity, and reliability of financial data and information. Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) provide a common set of rules and procedures recognized as the accepted standard for financial management and reporting.

In this chapter, we examine a number of concepts, tools, and decision-making approaches to understand and effectively use health care financial information as a strategic resource. Now more than ever is a time to recognize and make use of these concepts in light of the economic climate we live in and the many challenges facing health care organizations. We also highlight a broad number of roles and responsibilities health information managers may find themselves engaged in pertaining to the management and stewardship of an organization’s financial resources. Financial management principles apply not only to finance department staff and accountants but to an organization’s entire management team. The precise scope and nature of the role of HIM professionals in regard to financial management responsibilities will vary from one organization to another; however, a common theme prevails. First, the information found in health care records is at the core of patient care, clinical decision making, and ultimately delivering quality outcomes. At the same time, the economic aspects of providing health care and being able to communicate financial and monetary matters effectively, covering every facet of health care delivery, are essential. Health information managers have always contributed to the organization’s fiscal viability through productive and proficient data collection and information processing for patient care, reimbursement, research, and by management of the resources under their control. In today’s data-driven health care environment, it becomes increasingly clear that clinical and financial health information go hand in hand, and being able to analyze, interpret, communicate, and use this strategic resource offers even greater opportunities for health information professionals to flourish.

Historical perspective

Financial management in health care has become increasingly complex over the past 25 years. Concurrently, the roles held by the HIM professional and health information services have become pivotal positions in the fiscal success of any health care organization. The dependence on the health record’s content to define accurately and completely the services provided and conditions treated for reimbursement purposes have contributed to this escalation in status. Skilled HIM professionals have the expertise to analyze the health record and interpret for pertinent data and information to maximize reimbursement without compromising the integrity of data quality.

During this dynamically changing period, the financial aspects of health care organizations have become much more important. Health care managers not only must know how to adjust their operations to respond to the dynamics of a shifting economy and constantly changing regulatory requirements but must also understand the many concepts and principles of financial management. To use a sports analogy, a football quarterback must understand the entire play book to throw the football to the exact yard line on the field where the wide receiver is expected to run.

Payment for health care services

Perspectives on the significance of financial management in health care show no signs of a slowdown, especially as reimbursement for health care continues to receive increased focus. One only needs to look back at the substantial change that has occurred over the years. Back in the 1930s, the customary method of paying for health care was direct, out-of-pocket remuneration. Some payments were monetary, others were in goods. When hospitals started being used more often than physician offices or house calls, both hospitals and industry explored ways to insure for the cost of health care. This exploration resulted in the establishment of insuring agents that served as the forerunner for what became Blue Cross and led into multiple private insurance companies, both nonprofit and for profit. These companies provided a new service to the public: coverage for health care expense.

As more people paid health care insurance premiums, they began exercising their “right” to make use of services paid for by their premiums. Health care premiums are the dollars individuals and organizations pay to insurers in return for health care insurance coverage. The increasing use of health care services contributed to rising premiums and greater than anticipated demands on health care providers and organizations. The demand was but one factor leading to building more hospitals and more people seeking training in health care as physicians. Insurance provided an avenue that not only insured the individual but also assured the hospital that it could receive payment for the care provided. Such assurances were atypical before the 1930s. Those insured had no incentive to limit or judiciously seek health care services. Access to full or nearly full payments for services did not encourage hospitals to limit the realm of services provided or control duplication of services within the same community.

By the mid-1960s, social reform required the establishment of a government-subsidized health care program. This program became known as Medicare. The Medicare program further encouraged hospitals to provide services without regard to cost because most costs were reimbursed under the Medicare reimbursement program. Over the past 50 years, the government’s perspective has become one that embodies the philosophy that all citizens have a right to health care. This trend began with the passage of Titles 18 and 19 to the Social Security Act in 1965.

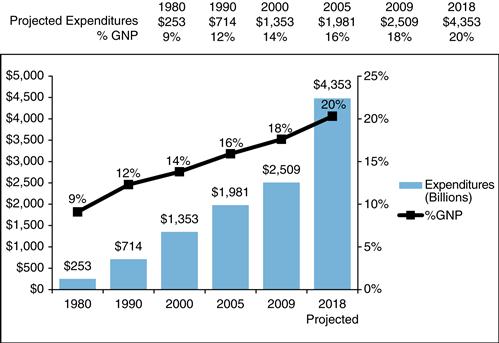

As health care expenditures continued to increase (Figure 17-1), the federal government found it necessary to impose controls on its insurance costs. It was not until the 1980s that the reimbursement formula was modified to restrict reimbursement and control the government’s expenditures for health care. In 1982, the Health Care Finance Administration (since restructured to become the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS]) implemented the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act. The law mandated a prospective payment system (PPS) for most hospital inpatient services. The PPS became effective in 1983. This program attempted to balance the payments made for the same services rendered by different providers and pay the providers on the basis of the diagnosis at a fixed rate. Diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) were established in the United States and case mix groups in Canada.

Reimbursement modifications occurred in the private insurance industry as well. Some contracts established between insurance companies and hospitals paid the hospital a specific rate for care provided to its subscribers (covered insureds). Different reimbursement methods now exist, including prenegotiated amounts, reimbursement based on a discount off billed charges, per diem payments, reimbursement based on audited costs, DRGs, ambulatory care groups, resource utilization groups, and payment for services at full billed or discounted charges. Reimbursement at billed or full charges seldom occurs anymore. Some insurance organizations provide payments directly to the insureds or subscribers, who then must pay the health care provider.

The sequence of events that have occurred over the past 50 years has created the third-party payer concept. A third-party payer (the insurance company) pays for services provided by health care organizations or practitioners to the “insured.” In addition, the “payer” often receives premium payments from the insured’s employer. Health insurance has become entwined with employee benefits rather than insurance purchased by the individual, as is the case for automobile or homeowner insurance. The employers have gained considerable purchasing power in regard to health insurance and, at the same time, have a significant interest in the cost of health care services. The federal government and state governments also cover or insure nonemployees in significant programs such as Medicare and Medicaid.

Reimbursement modifications have extended beyond hospital providers to home health agencies (converted from whole service cost based to discipline cost based), skilled nursing facilities (resource utilization groups), outpatient departments (ambulatory patient classifications), ambulatory surgery centers, rehabilitation facilities (case-mix function-related groups), and pharmacies (prescription drug tiered formularies).

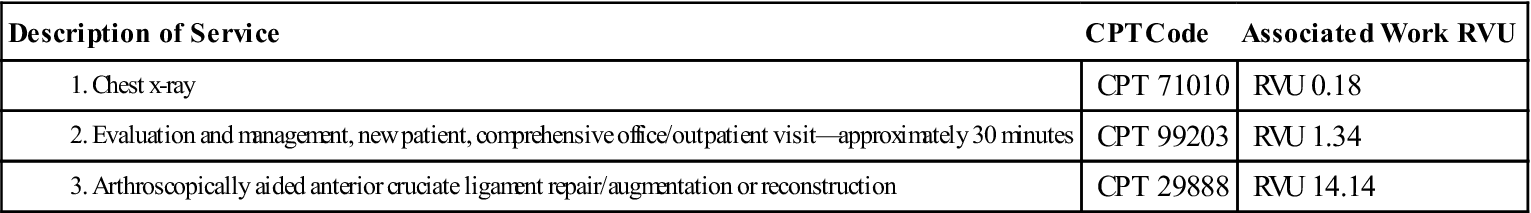

The philosophical change in reimbursement to control costs affected physicians and other independent practitioners as well. The resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS) was implemented in 1992. The intent of the RBRVS was to ensure equity in payment for like services. The scale assigns a certain number of units (or partial units) to each procedure of service. In effect, payments were based on current procedural terminology (CPT)–4 codes, regardless of the practitioner’s specialty.

Other attempts at controlling costs included reducing the options available to a person to obtain health care services. In the 1980s, the growth of managed care programs (e.g., health maintenance organizations [HMOs], preferred provider organizations [PPOs], and prepaid group practice plans) was significant. Growth continued through the 1990s. Some communities had as much as 60% of their insured population enrolled in a managed care program. The programs require the insured person to comply with specified rules of access, obtain approval for routine care, seek services from a preselected directory of providers, and fulfill other utilization requirements. Substantial financial disincentives are imposed on those who choose to receive services outside the predefined network of providers or without obtaining the necessary approvals.

In truth, health care costs increased uncontrollably when health care was paid for “in full.” Controls using a variety of methods, fee structures, prospective rates, access mandates, and so on have slowed the rate of increase in expenditures to some degree. Provider dropout through hospital closure and state-mandated authorization processes such as certificate of need programs to set up new services or purchase expensive equipment has reduced some duplication of services. However, even with the advancements and efforts that have been made in an attempt to control and maintain health care expenditures, most experts agree that the U.S. health care system is still considered to be one of the most costly and inefficient (Box 17-1).3 It is projected that health care expenditures will continue to outpace the rest of the economy and by 2018 will exceed 20% of gross national product (see Figure 17-1).

In 2008, there were more than 46 million individuals with no health insurance coverage, representing 15.4% of the U.S. population.4 One of the principle drivers for the increased numbers of uninsured is the high cost to employers offering health care benefits to employees. In 2008 much of health care insurance continued to be employment based, and businesses found it necessary to share the burden through increased cost to employees. The growth of personal out-of-pocket expenses continued to accelerate through higher employee premiums as well as the expansion of high deductible and consumer driven health plans with greater copayments, coinsurance, and spending caps. Simply put, employers have limited financial resources and seemingly endless competing needs for these same resources. In many cases, employers have even discontinued offering health benefits completely. This is particularly seen in small businesses or companies that are able to use greater numbers of part-time workers—employees who may not qualify for health care benefits.

The high cost of health care and how to make health care more affordable while expanding insurance coverage to all citizens has risen to the top of most business agendas and political policy debates. In 2009, the federal government passed economic stimulus legislation known as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), a big piece of which invests in health information technology initiatives to put into operation a nationwide health information network to assist in lowering health care costs and strengthening the economy. There is widespread consensus that information technology and the ability to deliver health information where and when needed is a centerpiece to answering the question of controlling health care costs. Beyond that, there remains much debate over the value and effectiveness of diverse market-based private insurance practices and government-run health reform proposals.

If past attempts to control costs are any predictor for the future, health care providers should prepare for decreased reimbursements for services rendered. It is essential for health care managers to provide services efficiently and effectively, at a cost lower than or equal to the payment that will be received. The health information manager’s role now includes many different skill sets and disciplines and much more than effective and efficient management practices.

Managing the revenue cycle

Because of the high cost of health care and corresponding financial pressures faced by most health care provider organizations and individual practitioners alike, significant emphasis is placed on generating revenue and maximizing potential sources of revenues. In accounting terms, an organization’s revenues can be classified as either operating revenue or nonoperating revenue. When we speak of accounting terms, we are referring to GAAP mentioned earlier. For the purposes of our discussion of managing the revenue cycle, we focus on operating revenues, which include those revenue sources generated from the actual delivery of clinical patient care activities and services; that is, charges for the services that are provided. Nonoperating revenues can also be important in contributing to the bottom line of health care providers and may include such items as gifts and donations, income from endowment funds, research grants, interest from investments, and other miscellaneous income.

Health information professionals have learned as part of their biomedical education that human beings are complex organisms comprising multiple interrelated systems; without the nourishment of constant blood flow, the human body would stop working. Much in the same manner as red blood cells and white blood cells make up the lifeblood contributing to the growth and overall health of the human body, organizations cannot survive without sufficient streams of revenue. Applying a similar analogy to financial management and specifically to the revenue cycle, without a constant flow of revenues and subsequent cash flow, health care organizations would cease to exist. For most health care organizations or providers, revenues result from performing the services and equate to the charges for services provided. Cash results from the collection of payments for services provided. You can think of revenue as what is earned and cash as what has been collected. A health care organization’s revenue stream and subsequent cash flow enable its ability to acquire and retain sufficient operational and capital resources for providing ongoing patient care services.

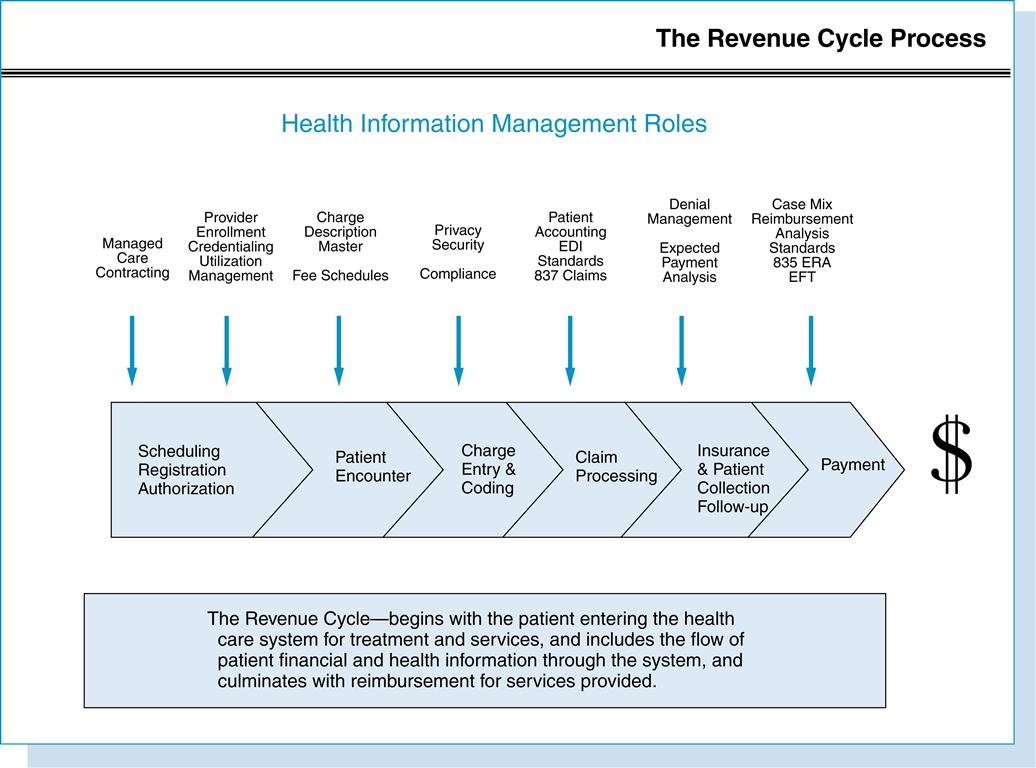

It is well documented that the revenue cycle and the management of an organization’s revenue streams can be a rather complicated process, particularly when striving to keep up with complex and constantly changing regulatory requirements, technology enhancements, and specific detailed reimbursement contracts. The scope and breadth of interrelated functions making up the revenue cycle comprise many essential HIM competencies, making HIM professionals well positioned to step in at almost any point in the revenue cycle. In many cases, HIM professionals may oversee the entire revenue cycle process for an organization.

Front-end activities

Most traditional forms of health care are not cash and carry that is paid for at the time of service but rather a complex network or group of operations and systems interwoven with multiple participants and administrative processes. Movements toward retail health care solutions, consumer-driven health plans, and point of service collection initiatives enabled by technology enhancements are beginning to change this dynamic for some consumer segments. In either case, when revenues are generated, any outstanding accounts receivables (dollar amount owed) that result are often an organization’s largest asset following its physical plant and facilities. The actual makeup of the revenue cycle can vary greatly from organization to organization and often is best described by breaking down into component front-end and back-end activities. The revenue cycle consists of all previsit and postcare activities and systems associated with a patient or consumer entering the health care system, the receipt of services, and eventually the provider being paid for the service (Figure 17-2).

Contracting

Because the major source of revenue for most health care organizations comes not from patients or the consumer but from third-party insurance companies, it is important for providers to understand and negotiate the best reimbursement contract terms up front. Of course, the effectiveness in negotiating payer contracts is often dictated by the power of the major health care players in the local market. Individual physicians in private practice may find it more difficult bargaining with a payer dominating the market. On the other hand, if the payer needs a certain hospital, medical specialty, or provider group in their network, the tables may be turned as far as negotiating. In addition to actual negotiated payment rates, it is important that specified reimbursement rules and such items as technical coding and billing requirements be identified beforehand and agreed to by both parties. Payer contracts are legally binding documents describing the obligations for both providers and payers in providing health care services to patients (e.g., insurance plan members or beneficiaries in the case of government payers). Contract language will typically include essentials for submission and payment of claims, including reimbursement specifics for modifiers, CMS’s Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS), medical necessity determination, services to be carved out (e.g., Behavioral Health, Vision, or Dental), and any contract exclusions. Language provisions will also be included describing provider requirements for granting payer access to confidential patient records and other personal health information (PHI). There are numerous opportunities for health information professionals to lend their expertise as part of the contracting process. Common contracted methods of reimbursement might include the following:

More contemporary methods include pay-for-performance arrangements and evidence-based care rates designed to provide reimbursement directed at improving quality of care rather than based solely on volume, or the amount of services and treatments provided. Both government and non-government payers may make available incentive payments for achieving agreed-on outcomes and levels of reporting for specified quality measures and measures groups, e-prescribing activities, and other evidence-based metrics. Federal legislation called the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008 (MIPPA) authorizes incentive payments to physicians who make use of new e-prescribing technology through 2012, at which time financial penalties accrue for those who have yet to adopt.5

After a provider has come to terms with a payer and is under an approved contractual agreement, the provider is considered a participating provider and agrees to provide services to covered plan members or Medicare beneficiaries and must abide by established payment rates. A nonparticipating (noncontracted) provider is considered out-of-network by the payer, which most frequently results in a reduced payment or nonpayment. Most payers offer out-of-network benefits, enabling the patient to receive care from a nonparticipating provider at a higher rate of coinsurance, which must be collected directly from the patient. In the case of Medicare, if an individual provider is considered nonparticipating, government regulations specify a limit on how much the patient can be charged.

Licensure and provider enrollment

Apart from actual payer contracts, government and nongovernmental commercial payers alike require providers rendering health services to patients to be fully licensed and fulfill rigid credentialing requirements. The credentialing process enables both payers and providers to document a certain standard of quality of care. Provider enrollment documentation must be completed before a payer granting billing privileges to individual providers. The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) establishes accreditation standards that payers and providers use to oversee the credentialing process. The credentialing process essentially provides a screening mechanism for verifying provider education, credentials, licenses, board certifications, clinical experience and practice history, and malpractice coverage and professional claims history. In the case of clinical laboratories, the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment (CLIA) of 1988 mandates completion of a certification process before obtaining billing privileges. Payers also require that a specific tax identification number be included as part of their enrollment information. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) requires health care business organizations and individual provider or group entities conducting business to file an application for obtaining a federal tax identification number. Depending on the terms of payer contracts, delays in completing and submitting provider enrollment licensing and credentialing information to a payer can delay or possibly prevent reimbursement all together. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) requires health care providers to obtain and use a unique National Provider Identifier (NPI) for health care transactions. HIM professionals already engaged in handling medical staff credentialing responsibilities will note that many of the same licensing and credentialing source documents already used in the medical staff office are needed for this integral front-end revenue cycle function.

Charge master—fee schedule

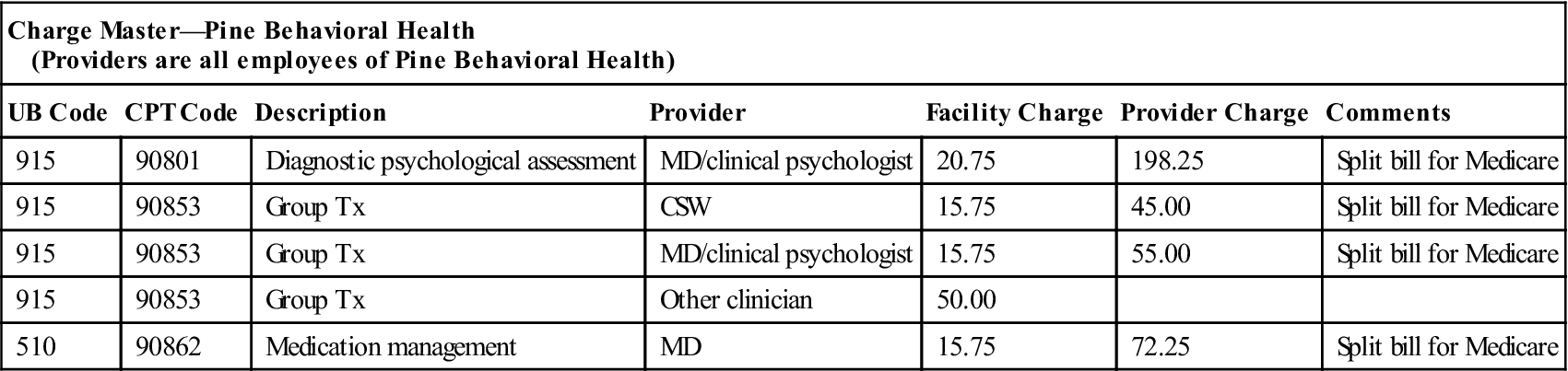

Because health care services rendered generate revenues, it is imperative that services be priced (charged for) effectively and that the price be consistent with the cost to provide the service and at a level above contracted rates for each given service. This requires regular analysis of contracted reimbursement rates and expenses associated with services or product costing. HIM professionals have access to all data associated with various clinical treatment and procedures to resolve health conditions because they have access to the health record. The HIM professional can be key to collecting and classifying tests and procedures performed for the various conditions treated. Likewise, HIM professionals can assess the various expenses (costs) associated with a service. Charges must be assigned so that costs are covered for the various supplies and services used. Each health care organization has a master charge list, sometimes called the charge master, charge description master (CDM), or fee schedule. This list reflects the charge for each item that may be used in the treatment of a patient and the charge for most services—that is, respiratory therapy treatments, physical therapy services, laboratory tests, and so on. The charge description master is most always automated and linked with the billing system. In some organizations, it is also linked with the clinical data system maintained by HIM services and can be used to perform fiscal-clinical analyses (Table 17-1). In many organizations, information system logic may be established to generate both technical and professional charges automatically.

Table 17-1

EXAMPLE FROM PINE BEHAVIORAL HEALTH CHARGE MASTER

| Charge Master—Pine Behavioral Health (Providers are all employees of Pine Behavioral Health) | ||||||

| UB Code | CPT Code | Description | Provider | Facility Charge | Provider Charge | Comments |

| 915 | 90801 | Diagnostic psychological assessment | MD/clinical psychologist | 20.75 | 198.25 | Split bill for Medicare |

| 915 | 90853 | Group Tx | CSW | 15.75 | 45.00 | Split bill for Medicare |

| 915 | 90853 | Group Tx | MD/clinical psychologist | 15.75 | 55.00 | Split bill for Medicare |

| 915 | 90853 | Group Tx | Other clinician | 50.00 | ||

| 510 | 90862 | Medication management | MD | 15.75 | 72.25 | Split bill for Medicare |

CSW, Clinical social worker; MD, medical doctor; Tx, therapy.

Associated with each service is a charge and either a CPT-4 code or a HCPCS code from the CMS Common Procedural Coding System. CPT-4 codes are an industry standard, updated annually by the American Medical Association. HCPCS codes are updated periodically by the CMS. Also, individual charge amounts can be affected by the addition of clinical modifiers. Modifiers are specific numerical or alpha codes that when appended to a given line-item charge can affect the level of reimbursement. The HIM professional’s knowledge of classification systems can be beneficial in ensuring that the master list is accurate and up-to-date at all times. Organizations may also maintain an expanded list of zero-charge house codes to gauge or report certain activities and services that are performed. This expanded list may assist in measuring activity and service volumes or account for resources used. An example of these nonbillable codes might comprise specific CPT Category II codes used for measuring quality indicator usage as part of the physician quality reporting initiative (PQRI) sponsored by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

Registration and admitting—access management

The health care delivery system requires that numerous front-end activities take place before a patient ever receives treatment or health care services. For a patient to be effectively scheduled and registered for admission to a hospital or other health care facility, or for the patient to be seen by an individual medical provider, numerous previsit verification processes are used to capture necessary information for billing purposes. In addition to appropriately handling all the clinical aspects of a patient registration leading up to the actual encounter, the registration function requires the collection of complete and accurate demographic, financial, and insurance information. The actual process of obtaining this information can be cumbersome and may include accessing a multitude of varying sources and systems to effectively gather. Not only must providers verify whether a patient is covered under a given health plan, they must also determine what specific benefits are available. This task becomes even more complex when considering the increasing variations of copayments and deductibles and other complexities coinciding with the growth of consumer-driven health plans. Failure to register a patient accurately and obtain all necessary demographic, financial, and insurance information on the front-end can lead to missed insurance authorizations, costly claim errors, claim denials, and subsequent reimbursement delays later on in the revenue cycle.

Health care payer policies set administrative standards that necessitate that some treatments and services require a referral (formal request) from a physician before the patient can be seen by another specialist provider. Other policies mandate that hospital or physician services be precertified (preapproved) by the payer before the patient receives services. This is particularly true for hospital admissions and surgical procedures and enables the payer to monitor and control potential costs (expenditures) before services are performed.

Utilization management—case management

Because health care is expensive, payers and providers alike expend significant resources and efforts toward determining the medical necessity and appropriateness of patient care. A patient’s insurance and coverage requirements can change quickly, making it essential that services be constantly evaluated and authorized in advance. A payer may deny services or refuse to reimburse providers if a patient’s care or course of treatment does not meet certain clinical protocols and established benchmarks. Services that are not authorized result in lost patient revenues. Using the documentation found in the patient’s health record, utilization management staff can evaluate the appropriateness and necessity of medical services on the basis of established guidelines and clinical criteria. Utilization staff members perform upfront prospective reviews and concurrent and retrospective reviews to evaluate the medical necessity of procedures, admissions, treatment plans, length of stays, and discharge plans.

Patient encounter

Whether it is an admission to the hospital, skilled nursing facility, a surgical procedure, clinical lab test, x-ray examination, physician office visit, home health visit, or any other mode of patient treatment, it is the actual service and corresponding documentation that provide the ability to generate revenue. Not only is documentation of the patient encounter necessary for continuity of care purposes, it also serves as a source document for billing purposes. Source documents may be in the form of electronic health records and automated information systems or traditional paper health records and encounter forms. The adage that “if it is not documented it is not done” holds true. Billable services must be appropriately documented, and failure to do so can result in nonpayment and lost revenue.

Coding-charge capture

In many health care organizations, there can be one distinct information system with billing and financial functions tied seamlessly to the electronic health record. Alternatively, there may be several order entry and ancillary clinical systems interfacing with the core billing system. Many of these information systems may include system logic established to automatically generate both technical facility charges and professional charges. In some organizations, charges may be manually entered from encounter forms decentralized in provider offices or input centrally in data control. In yet other cases, complex manual coding or computer-assisted coding may be required before a charge being released to the billing information system and for a claim or patient bill to be generated. In these cases, a reasonably complete clinical health record must be accessible to coding staff to meet the goal of timely and accurate coding and submission of data for billing. Physicians and other clinicians support this activity by timely, accurate, and complete documentation. Coding staff may also confer with physicians and other practitioners to obtain information to clarify a code assignment.

As we mentioned earlier, cash flow is the lifeblood of any organization. The HIM manager holds an important key to expediting the time lapse between the recording of revenue and the receipt of cash. This key is in the coding and classification function. The health information manager must implement procedures and practices to monitor work flow to ensure the timeliness of work flow through the coding and classification section of the department and identify causes for any delays (Box 17-2).

Because codes are required for proper billing and complete accurate codes are required for optimum reimbursement, the health information manager must ensure that the coding and classification staff members are up-to-date in their work and in the application of coding rules and principles. This holds true whether manually assigning codes from paper or electronic record documentation or functioning to validate and edit codes generated from computer-assisted coding tools.

Back-end activities

Keeping in mind that the revenue cycle is composed of an interwoven system with multiple participants and systems, the actual distinction between front-end and back-end revenue cycle activities will vary depending on such reasons as organizational structures, staffing patterns, historical performance, or information systems within the organization.

Patient accounting

The patient accounting department, patient financial services, or business office typically has primary responsibility for the back-end billing, collection, and cash processing associated with patient accounts. Many patient accounting departments also have responsibility for the front-end registration or patient access function. With the advent of DRGs, a cooperative relationship has evolved between the HIM department and patient accounting. The need to keep each other informed of accounts receivable status requires that each area’s manager and staff work closely and respect the other’s constraints. Each area has expertise that should be shared with the other. The HIM department has a good working relationship with medical staff members. Patient accounting has extensive experience working with patients and insurance companies to collect balances due on the accounts. Sharing techniques with each other on how best to get results from people benefits both departments. Each department receives newsletters, regulatory notices, and other information that can be shared with the other to allow both departments to be more knowledgeable.

Each area works with medical terminology. The staff members in patient accounting are often trained from within. HIM professionals can teach medical terminology to the patient accounting staff and educate them in medicolegal aspects, such as patient confidentiality and proper release rules concerning personal health information (PHI).

Patient accounting is expected to manage billing and collection of revenue earned by the organization, otherwise known as managing the accounts receivable. The HIM department can also support increased reimbursement by ensuring that the organization’s CDM (master listing of services) is kept up-to-date with current CPT-4 codes.

Claims processing

Generating clean and accurate claims has become complex with the number of payers and the variety of administrative and technical reimbursement rules associated with obtaining payment for health care services. Health care providers use secure in-house billing systems and external clearinghouse vendors to define specific claim billing formats and edit checks unique to particular clinical services and individual payers. Example claim edits might include the following:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree