Data reporting, interpretation and use

Kay Clements and Shannon Houser

Objectives

• Describe various registries and their purposes.

• Discuss the uses of registry data.

• Describe and develop data collection methods.

• Discuss the importance and methods of formulating a data dictionary for a health information system.

Key words

Abstracting

Active case ascertainment surveillance systems

Applied research

Attribute

Basic research

Benchmarking

Bioterrorism

Case

Case eligibility

Case finding

Clinical case definition

Clinical decision support

Comorbidity

Core measure

Data

Data dictionary

Data element

Data warehouse

Differentiation

Domain

Emergency Response

Entities

Epidemiologic case definitions

Etiology

External users

Field

Follow-up

Grading

Healthcare data users

Hospital cancer data system

Incidence

Internal users

Logical data model

Major birth defects

Metadata

Morphology

Outcome

Passive case ascertainment surveillance systems

Pay-for-performance

Population-based cancer registry

Primary data/Primary Source of Health Data

Public Health

Public Health Informatics

Record

Reference date

Registry

Research

Secondary data/Secondary Source of Health Data

Stage

Surveillance

Table

Topography

Value/coding

Abbreviations

AAFP—American Academy of Family Physicians

ACG—Adjusted Clinical Group

ACIP—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

ACS—American College of Surgeons

ACSCOT—American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma

AHRQ—Agency for Health Care Research and Quality

AIS—Abbreviated Injury Scale

AJCC—American Joint Committee on Cancer

ANSI—American National Standards Institute

APACHE—Acute Physiology, Age, and Chronic Health Evaluation

APR-DRG—All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups

ASTM—American Society for Testing and Materials

CCS—Clinical Classification Software

CDC—Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CHCA—Child Health Corporation of America

CHDA—Certified Health Data Analyst

CMS—Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

CoC—Commission on Cancer

CPT—Current Procedural Terminology

CTR—Certified Tumor Registrar

DCE—Distributed Computing Environment

DCG—Diagnosis Cost Group

DHHS—Department of Health and Human Services

EHR—Electronic health record

EMS—Emergency medical system

FIGO—International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

FORDS—Facility Oncology Registration Data Standards

HCUP—Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

HEDIS—Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set

HIM—Health Information Management

HISPP—Healthcare Informatics Standards Planning Panel

HITSP—Healthcare Information Technology Standards Panel

HL7—Health Level 7

HOI—Health Outcomes Institute

ICCS —International Classification of Clinical Services

ICD-10-CM—International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification

ICD-9-CM—International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

ICD-O-3—International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition

IDDM—Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus

IWG—Informatics Working Group

MACDP—Metropolitan Atlanta Congenital Defects Program

MHCA —Mental Health Council of America

NAACCR—North American Association of Central Cancer Registries

NACHRI —National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions

NCDB—National Cancer Data Base

NCI—National Cancer Institute

NCQA—National Committee for Quality Assurance

NCRA—National Cancer Registrars Association

NIDDM—Non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

NIH—National Institute of Health

NOTA—National Organ Transplant Act

NTDB—National Trauma Data Bank

NVAC—National Vaccine Advisory Committee

OPTN—Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

OSF —Open Systems Foundation

PEPPER —Program for Evaluating Payment Patterns Electronic Reports

ROADS—Registry Operations and Data Standards

SEER—Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

SQL —Standard Structured Query Language

TJC—The Joint Commission

TNM—Tumor, Lymph Node, and Metastases

UHC —University HealthSystem Consortium

UNOS—United Network for Organ Sharing

WHO—World Health Organization

XML—Extensible Markup Language

Student Study Guide activities for this chapter are available on the Evolve Learning Resources site for this textbook. Please visit http://evolve.elsevier.com/Abdelhak.

When you see the Evolve logo  , go to the Evolve site and complete the corresponding activity, referenced by the page number in the text where the logo appears.

, go to the Evolve site and complete the corresponding activity, referenced by the page number in the text where the logo appears.

This is a revision of the chapter in the previous edition authored by Sue Watkins, RHIA, CTR.

Significant portions of Chapter 13 related to data dictionaries and decision support were adapted from chapters by Maida Herbst and Kathleen Aller in Electronic Health Records: Changing the Vision.

Health care data

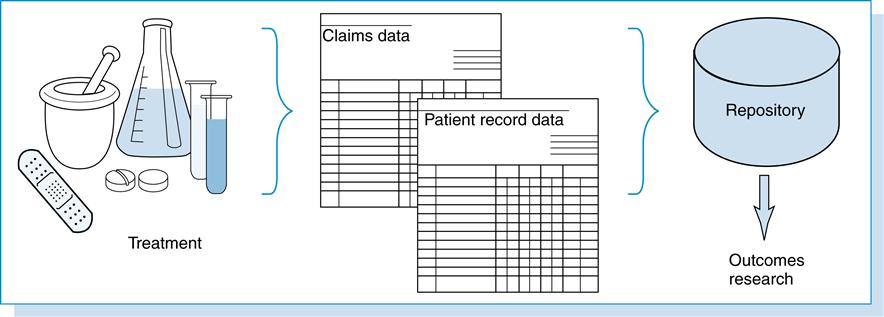

Data can be defined simply as “factual information, especially information organized for analysis.”1 Health care data are created from a patient’s health-related event as depicted in Figure 13-1.

This figure illustrates, in the health care environment, a patient receiving services in the form of prescribed medications, diagnostic testing, treatment, and/or medical care. From these encounters, health care data are recorded in the patient’s health record, and pertinent information is coded and abstracted for reimbursement. The patient’s health record is considered a primary source of health data. Data generated from these individual health care encounters can be stored in databases, aggregated, and used by various health care individuals, organizations, and agencies for multiple purposes. These databases represent secondary sources of health data.

Health care data users

Health care data users range from individual patients, health care providers, and organizations to epidemiologists, researchers, health care payers, grants funding organizations, politicians, and public agencies. Data users can be divided into two groups, internal users and external users. Individuals who are affiliated with the organization are referred to as internal users. Users from outside the organizations are considered external users.

Health care data reporting and uses

The uses vary as much as the users. The primary purpose of health care data is to document the care and treatment provided to the patient. Secondary uses include validation of medical services for reimbursement by health care payers, evaluation and planning related to health care services, surveillance and prevention of disability and disease, health policy analysis, measurement and tracking outcomes of treatment, and assisting individuals and communities in achieving better health.

Health care data are often used in the form of coded data that translate narrative prose into numerical or alphanumerical codes (numbers and letters). This information can be recoded or translated into other coding schemes beyond the original through a mapping process. Coded data are discussed in depth in Chapter 6.

Given the importance of these data, attention to quality is paramount. The accuracy of coded data is based on how well the codes match the clinical information they represent. The quality of the data can be affected by several factors, including how it is generated, the training of the individuals who are assigning the codes, and the supporting documentation that is available for review. Coded data are compiled from individual health encounters into large databases. Within databases, it is possible to generate a variety of descriptive reports from the aggregate data, including the number of each type of diagnosis patients have during a given time period, the number and type of procedures, and provider statistics and demographics. These summary reports are indices of the types of diagnoses treated, procedures performed, and providers who treated the patients in a given setting during a given time period.

As previously mentioned, information contained in the actual patient record is considered primary data, whereas the information that is generated from the record is considered secondary data. Both primary and secondary data are stored in databases. This chapter highlights important uses of health data to include an overview of selected registries currently tracking patient information and defines public and private users of health data. The development of data dictionaries and standards is also discussed.

Health care organizations generate so much health care data (administrative, clinical and financial) that without tools for analysis and interpretation, the data in its raw form cannot be used in decision making or performance improvement. The health information management (HIM) practitioner is responsible for monitoring and auditing HIM operations to ensure that accurate data is abstracted, coded, and entered by HIM personnel. In addition to the HIM department, other areas in the health care facility (quality, performance improvement, etc.), abstract and enter data into various databases, and the organization may submit data to organizations externally for the purposes of analysis, interpretation, benchmarking, and reporting. Reports that are generated from such efforts can be categorized by organization and purpose.

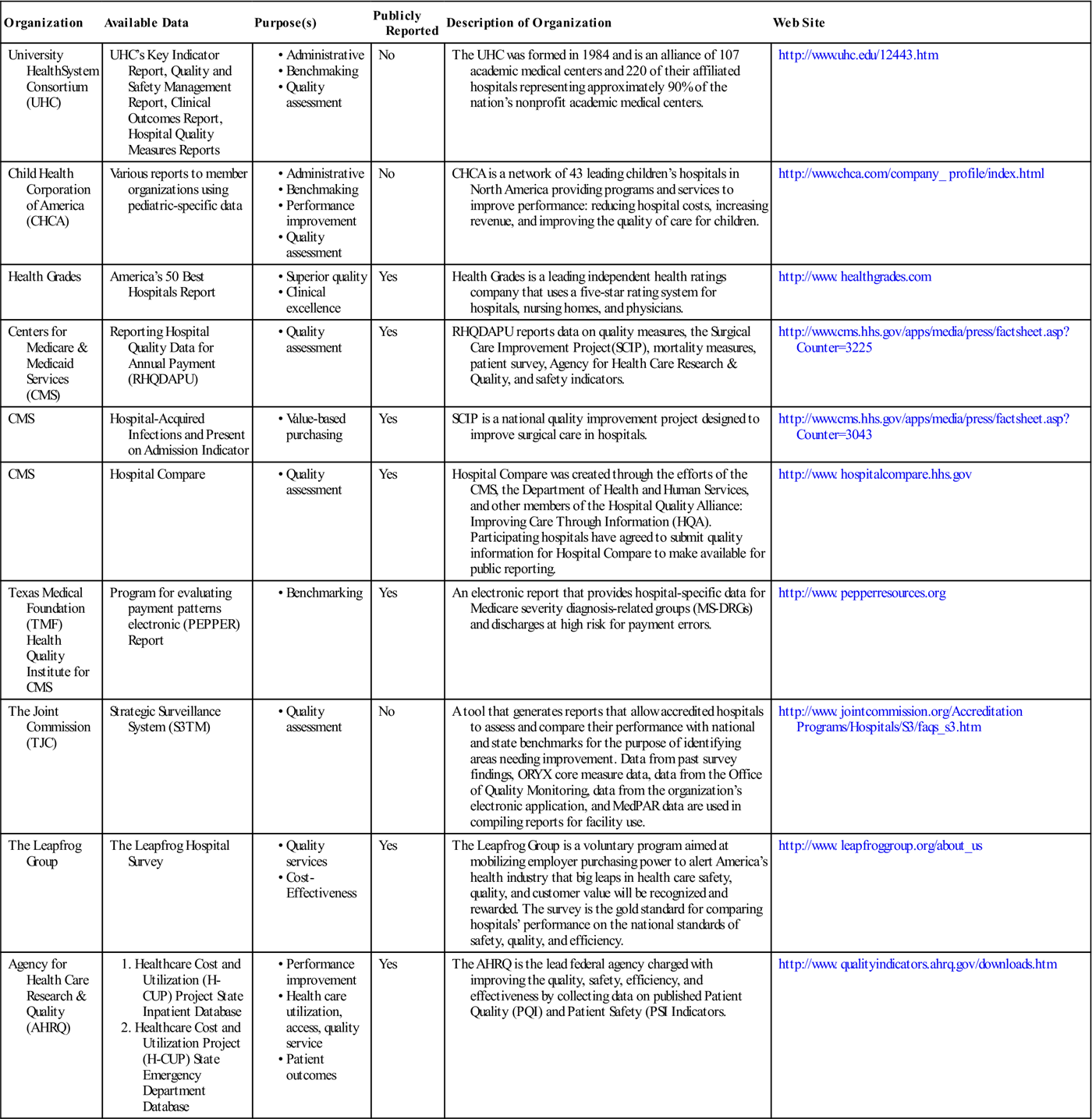

See Table 13-1 for examples of the private and public organizations for which data analysis, interpretation, and reporting requirements need to be well known by HIM practitioners.

Table 13-1

EXAMPLES OF PUBLIC AND PRIVATE USERS OF HEALTH CARE DATA

| Organization | Available Data | Purpose(s) | Publicly Reported | Description of Organization | Web Site |

| University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC) | UHC’s Key Indicator Report, Quality and Safety Management Report, Clinical Outcomes Report, Hospital Quality Measures Reports | No | The UHC was formed in 1984 and is an alliance of 107 academic medical centers and 220 of their affiliated hospitals representing approximately 90% of the nation’s nonprofit academic medical centers. | http://www.uhc.edu/12443.htm | |

| Child Health Corporation of America (CHCA) | Various reports to member organizations using pediatric-specific data | No | CHCA is a network of 43 leading children’s hospitals in North America providing programs and services to improve performance: reducing hospital costs, increasing revenue, and improving the quality of care for children. | http://www.chca.com/company_ profile/index.html | |

| Health Grades | America’s 50 Best Hospitals Report | Yes | Health Grades is a leading independent health ratings company that uses a five-star rating system for hospitals, nursing homes, and physicians. | http://www. healthgrades.com | |

| Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) | Reporting Hospital Quality Data for Annual Payment (RHQDAPU) | Yes | RHQDAPU reports data on quality measures, the Surgical Care Improvement Project(SCIP), mortality measures, patient survey, Agency for Health Care Research & Quality, and safety indicators. | http://www.cms.hhs.gov/apps/media/press/factsheet.asp?Counter=3225 | |

| CMS | Hospital-Acquired Infections and Present on Admission Indicator | Yes | SCIP is a national quality improvement project designed to improve surgical care in hospitals. | http://www.cms.hhs.gov/apps/media/press/factsheet.asp?Counter=3043 | |

| CMS | Hospital Compare | Yes | Hospital Compare was created through the efforts of the CMS, the Department of Health and Human Services, and other members of the Hospital Quality Alliance: Improving Care Through Information (HQA). Participating hospitals have agreed to submit quality information for Hospital Compare to make available for public reporting. | http://www. hospitalcompare.hhs.gov | |

| Texas Medical Foundation (TMF) Health Quality Institute for CMS | Program for evaluating payment patterns electronic (PEPPER) Report | Yes | An electronic report that provides hospital-specific data for Medicare severity diagnosis-related groups (MS-DRGs) and discharges at high risk for payment errors. | http://www. pepperresources.org | |

| The Joint Commission (TJC) | Strategic Surveillance System (S3TM) | No | A tool that generates reports that allow accredited hospitals to assess and compare their performance with national and state benchmarks for the purpose of identifying areas needing improvement. Data from past survey findings, ORYX core measure data, data from the Office of Quality Monitoring, data from the organization’s electronic application, and MedPAR data are used in compiling reports for facility use. | http://www. jointcommission.org/Accreditation Programs/Hospitals/S3/faqs_s3.htm | |

| The Leapfrog Group | The Leapfrog Hospital Survey | Yes | The Leapfrog Group is a voluntary program aimed at mobilizing employer purchasing power to alert America’s health industry that big leaps in health care safety, quality, and customer value will be recognized and rewarded. The survey is the gold standard for comparing hospitals’ performance on the national standards of safety, quality, and efficiency. | http://www. leapfroggroup.org/about_us | |

| Agency for Health Care Research & Quality (AHRQ) | Yes | The AHRQ is the lead federal agency charged with improving the quality, safety, efficiency, and effectiveness by collecting data on published Patient Quality (PQI) and Patient Safety (PSI Indicators. | http://www. qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/downloads.htm |

Benchmarking

Health care organizations benchmark or compare their organizations against peer organizations that are known for their excellence. In today’s competitive environment with the focus on patient safety and the required reporting of patient safety and quality indicators, benchmarking has become a common tool in health care organizations. Benchmarking is discussed in more detail in Chapter 12.

Clinical decision support

Clinical decision support is typically presented as a system that brings knowledge to caregivers to assist them in making decisions about patient care. The system may generate an alert for an abnormally high laboratory test result or for a patient taking two medications that may interact negatively. The caregiver is then given the opportunity to review the situation and determine the appropriate course of care. The system can also automatically provide time-based reminders (i.e., this patient is due to have a routine bone density screening). Clinical decision support systems may provide links to the caregiver to other resources. These resources may be clinical guidelines or reference materials that can be accessed online. The overall objective is to bring knowledge resources to the caregiver in real time during the delivery of care process. A clinical decision support system includes a controlled vocabulary, a central data repository with appropriately structured clinical data, a knowledge representation scheme, an inference engine, and output mechanisms such as the electronic health record (EHR).

Consumer education

Through the efforts of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Department of Health and Human Resources, and members of the Hospital Quality Alliance (HQA), data on the quality of health care services has been made available to the public with the purpose of making the public a better informed consumer of health care services. This quality tool was developed for Medicare beneficiaries to locate information on how well patients with specific medical condition or undergoing specific procedure are taken care in hospitals but is available publicly for use.2

Performance management

The Joint Commission uses data from core measures to evaluate the quality improvement process. The data are transmitted to the Joint Commission from the accredited health care organizations. After transmission and evaluation, the quality data are provided to the public. It is also used to assess the Joint Commission accreditation and by health care organizations to internally analyze areas that can be improved.3 Performance measurement is used by health care organizations to evaluate and support performance. It is also used externally, to show accountability to consumers, payers, and accreditation organizations. It provides statistically valid, data-driven information. This enables a health care organization to evaluate itself. This type of information is particularly beneficial to consumers, enabling them to make critical decisions about where to seek quality health care.

For example, a section of the Joint Commission Web site discusses the derivation and reporting of core measures. The Specifications Manual for National Implementation of Hospital Core Measures, Version 2.0, provides information about how the care provided for patients with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, pneumonia, pregnancy and related conditions, and surgical infection prevention are measured. Information about these areas are continuously monitored and reported to the Joint Commission. The statistics derived from these data is one area of focus that the Joint Commission uses to prepare for an accreditation visit. The CMS is also using core measures to monitor the quality of care for its Medicare beneficiaries.

The Joint Commission’s Web site has a section called “Quality Checks” where anyone can locate the accreditation status of accredited organizations. Consumers can search for accredited organizations to find information about the services provided and the organization’s performance on the basis of various measures, including the core measures.4

Planning and assessment

As discussed earlier in the chapter, information from the various disease registries can be used by organizations to assess services and quality of care as well as to assist in planning. For example, American College of Surgeons (ACS)–approved cancer programs publish an annual report that provides summary information about the treatment provided to cancer patients and how that care compares with the care in other ACS-approved programs throughout the country. The data from the annual analysis can also help determine future patient needs for expansion of facilities and services.

Similarly, hospital discharge data can be used for strategic planning and outcome analysis. For example, the Intermountain Heath Care System, a nonprofit integrated health system in Salt Lake City, uses statewide data to compare itself with other organizations. Further, the New Hampshire Hospital Association develops an annual market share report. This allows hospitals to evaluate their market position and to determine how to position themselves and reallocate resources in a way that is beneficial to both the institution and the patient population it serves.5

Regulatory reporting

The health care industry is highly regulated, and health care organizations are required to report data to federal, state, and county agencies, as well as voluntarily reporting to accrediting bodies, such as the Joint Commission. As Chapter 1 mentions, the data reported by health care facilities are focused on access, quality, utilization management, patient outcomes, and cost of care. With the federal government’s emphasis on educating the public and making people informed consumers of health care services, it is in the health care facility’s best interest to report accurate data. Public reporting of data from public and private Web sites such as Hospital Compare6 and Health Grades7 allow consumers to identify facilities with lowest average length of stay, the lowest cost for performing specified services, and the mortality rate of medical and surgical services in the health care facility. Health care organizations also join consortia and share data for benchmarking within their peer groups. This information is not publicly available but is accessible to members only.

Registries overview

A registry is a systematic collection of data specific to a type of disease (e.g., cancer, acquired immune deficiency syndrome), exposure to hazardous substances or events (such as Agent Orange), or trauma and treatment (such as implanted medical devices). The data collected, methods of data collection, reports generated, and the uses vary with the kind of registry. Registries provide surveillance (collection, collation, analysis, and dissemination of data) mechanisms and, for some, incidence (occurrence) measures. A registry can be established for any disease; an overview of the characteristics of well-known registries will be provided in this chapter. Registries can also vary by location or type of agency. Some are specific to an organization such as a hospital.8 Others are operated by a governmental agency and collect data for a geographic area such as a city, county, or state.

Case definition and eligibility

A case is defined as a person with a given disease or condition that will be included in the registry. Criteria for the disease or condition are established to determine who should be included. The decision to enter the person into the registry is based on the established set of criteria. Some definitions are defined as reportable conditions by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as epidemiologic case definitions. These are diseases that must be reported to a public health agency. Epidemiologic analysis is then undertaken on the basis of the specific issues of interest regarding the disease being studied.

A clinical case definition may be established as well. A clinical definition is a list of signs and symptoms that establish a clinical diagnosis. A clinical case may be reported as a reportable disease if it meets the epidemiologic case criteria. In addition to the clinical diagnoses, other criteria may need to be met for the condition to meet the epidemiologic definition. A patient may have the clinical signs and symptoms requiring treatment and yet may not meet the strict definition for reporting designated by the CDC.9

Case definitions are provided for all reportable diseases, and the case definitions for specific types of registries are discussed later in applicable sections of the chapter.

Case finding

Case finding is the method through which all the eligible cases to be included in the registry are identified, accessioned into the registry, and abstracted. Case finding mechanisms should be redundant and include multiple methods to identify all the cases. This may result in the same patient being identified more than once; care should be taken only to include a patient once in the database. For example, receiving information from multiple data sources such as the pathology department or laboratory, the HIM department, the radiology department, the operating suite, and outpatient departments that may interact with the patients who are served by the registry will likely result in identifying several episodes of care for the patient. Depending on the type of registry, the various treatments will be denoted for the patient, or the patient is simply accessioned, and the abstract is completed and reported to the registry involved.

Abstracting

Generally, a set of predetermined data is obtained from the patient record and related sources through a process called abstracting. These data items are collected because of their relevance to the disease or condition addressed in the registry. Abstracts are prepared for each case and then form the information included in the database. Abstracting this information provides a succinct summary characterizing various issues including demographic information about the patient, diagnostic information, treatment data, outcome of treatment, and follow-up information.

Follow-up

An important function in the cancer registry is the follow-up conducted on patients after they are accessioned and entered into the database. Tracking the continued well-being of the patient and determining patient status at specified intervals is a major focus for Certified Tumor Registrars (CTRs). The ACS also requires a minimum percentage of follow-up for the cancer registry to maintain their approved status.

Registry quality control

Visual and computerized checks on data entered into the database should be performed by the personnel responsible for the database of the registry. This may be required by the organization external to the registry or simply to ensure that the database has consistent, complete, accurate data. Accuracy and completeness of data are important to ensure data integrity. The value of registry data is directly related to the validity of the data collected. Generally, to ensure data validity, a systematic quality control sampling of 5% to 10% of all cases in the registry should be reviewed for data quality.10 The linkage of computerized information may allow cross-referencing of data to ensure that all cases have been included and that the data elements in the records match other records.

Confidentiality of registry information

Registries contain patient-identifiable information that is derived from primary patient record information. All information in the registry must be kept confidential. Confidentiality policies and procedures are required in all phases of registry operations and should address protection of the privacy of individual patients, facility information, and the privacy of the physicians and health care providers who report the cases. They should also provide public assurance that the data will not be abused and that all confidentiality-protecting legislation or administrative rule(s) will be enforced. As a result of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, health care organizations are required to track patient registry information that is reported externally to state agencies to provide an accounting of disclosures to a patient, if requested.11

Cancer registries

Cancer registries are described in this chapter in more detail than other registries because they are the most common type of registry. These registries are often located within the HIM department, and many Certified Cancer Registrars have a HIM education or HIM credentials. Cancer registries are located in hospitals of all sizes and in every region of the country. In addition, all states have central or population-based cancer registries. Understanding the fundamentals of cancer registries provides the reader with an excellent foundation for developing other types of registries. The collection, retrieval, and analysis of cancer data by cancer registries are important to physicians, epidemiologists, and researchers concerned with assessing cancer incidence, treatment, and end results.

The purpose of the hospital cancer data system is to collect and maintain information on every patient with cancer from the initial date of diagnosis or treatment until death. The information collected furnishes the health care team with outcome data that enable them to see the results of their diagnostic and therapeutic efforts and provide them with the tools to improve patient care.

Hospital-based cancer registries or their equivalents have existed in the United States for many decades. Reports on cancer experience were issued in the late 1800s from such institutions as the American Oncologic Hospital in Philadelphia, the General Memorial Hospital in New York City, the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, and Charity Hospital in New Orleans.12 In the 1920s, the ACS asked its members to submit information on living patients with bone cancer. Subsequent requests were made later in the same decade for data collection on cancer of the cervix, breast, mouth and tongue, colon, and thyroid. In 1930, the ACS’s Commission on Cancer developed standards for hospital cancer clinics and began surveying facilities. By 1937, there were 240 approved cancer clinics, but it was not until 1956 that a cancer registry providing lifelong follow-up of cancer patients became a requirement for an approved cancer program.13

The first central registry was established in Connecticut when a group of New Haven physicians began compiling data that showed a steady increase in the cancer rates in their community. The physicians proceeded to start cancer clinics in their hospitals and to maintain uniform records. The Connecticut Medical Society formed a Tumor Study Committee and was instrumental in getting legislation passed that created the Division of Cancer and Other Chronic Diseases in 1935. In 1941, statewide cancer surveillance began when a team from the division visited each hospital and abstracted data from the records of all patients with cancer for the period 1935 through 1940.13

The National Cancer Act of 1971 mandated the collection, analysis, and dissemination of data for use in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer. This mandate led to the establishment of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, a continuing project of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The SEER Program operates population-based cancer registries in various geographic areas of the country covering about 14% of the U.S. population. The selection of demographic areas is based primarily on the areas’ epidemiologically significant subgroups to provide a sampling of the U.S. population. Trends in cancer incidence, mortality rates, and patient survival in the United States are derived from this database.14

With the passage of the Cancer Registries Amendment Act (Public Law 102-515) in 1992, a national program of population-based cancer registries was created. Funding of $16.83 million was allocated by Congress for 1994 to set up statewide registries in states where none existed and to enhance existing registries. Today, there are more than 2000 hospital-based cancer registries, and all states have population-based registries. The categories of cancer registries are generally defined as hospital based or population based.13

Hospital cancer registries

The primary goal of hospital-based cancer registries is to improve patient care. The cancer registry provides a system for monitoring all types of cancer diagnosed or treated in an organization. The data collected are used to optimize care for patients with cancer, to compare the institution’s morbidity and survival rates with regional and national statistics, to determine the need for professional and public education programs, and to help allocate resources.8

Hospital-based registries may be in single-institution or multi-institution settings, military hospitals, managed care programs, or free-standing treatment facilities. The patient care-oriented goal usually dictates the type of data collected. Data items collected include patient identification and demographic information, cancer diagnosis, treatment rendered, prognostic factors, and outcome.

A hospital cancer registry is one of the components of a cancer program approved by the ACS Commission on Cancer (CoC). The latest edition of the Cancer Program Standards, available on the CoC’s Web site, delineates the total program requirements.

Go to the Evolve Web site and view the latest edition of the Cancer Program Standards available from the ACS Commission on Cancer.

Hospitals are required by law to report cancer cases to a state registry but not to have an ACS-approved cancer registry. A hospital-based registry may be associated with a population-based registry (such as a registry operated by the state government); the latter often supports and facilitates the hospital’s efforts as a major source of its data. Support from the population-based registry may consist of analyzing data, generating reports that allow comparison of data, providing data collection software, assisting in quality improvement activities, and providing professional training to the hospital cancer registry staff.

The case eligibility for most cancer registries is defined by all the organization’s patients diagnosed (clinically or histologically) or treated for active diseases on or after the reference date or beginning of the registry are eligible for inclusion. For example, patients who were diagnosed and are being treated at the hospital, patients diagnosed at autopsy, patients who were diagnosed elsewhere and are receiving all or part of their first course of therapy or whose therapy was planned at the hospital, and patients who were diagnosed at the hospital and are receiving all their first course of therapy elsewhere should be included in the registry. The registry’s policy and procedure manual will define specifically the types of cases to be included.

Accessioning

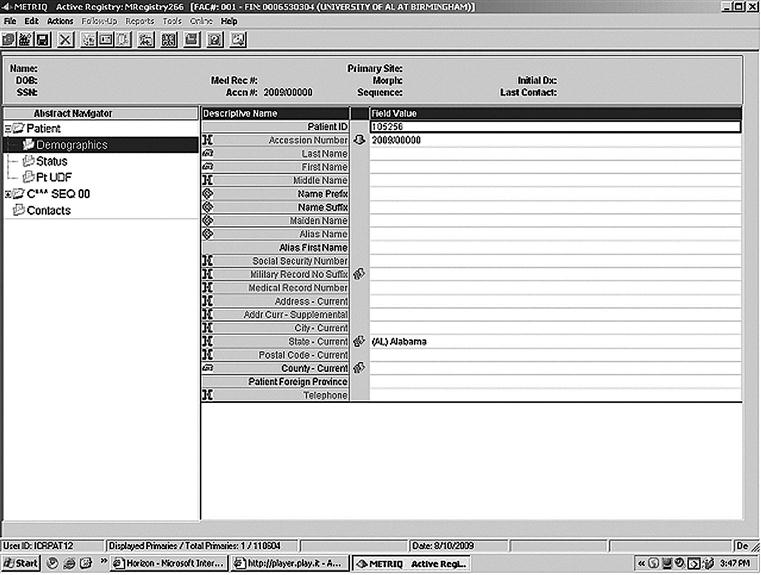

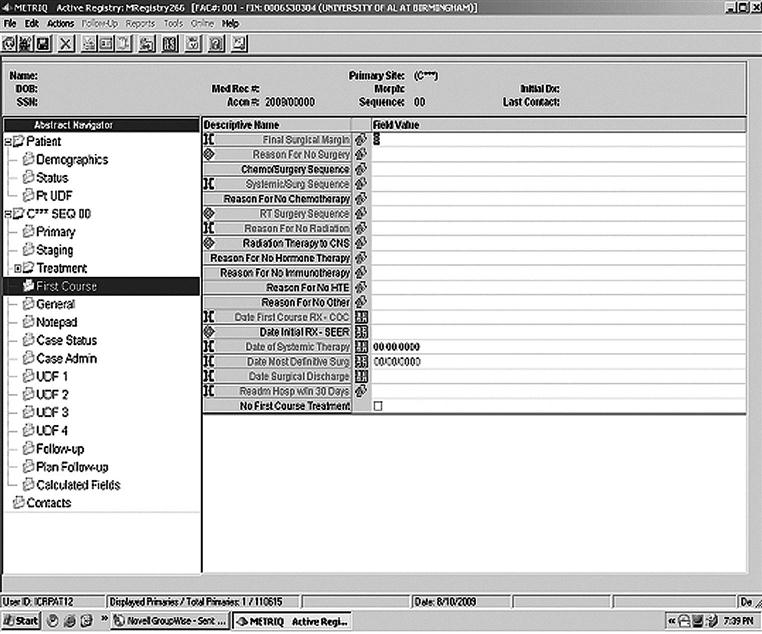

When patients are determined eligible and are added to the registry, they are said to be accessioned into the registry. A screen print used to accession a patient is shown in Figure 13-2.

The ability to identify every reportable case of cancer is essential to the success of a cancer registry system.15 The case finding system must include all points of service from when patients enter the health care delivery system for diagnostic or therapeutic services for the management of cancer.16 The primary case finding sources are the pathology department, HIM department information, and outpatient services areas. As a key resource, cancer registry personnel examine the reports from the pathology department for all pathologic diagnoses of cancer. The types of reports include surgical specimen, autopsy, bone marrow, hematology, and cytology reports. The second most common source is the organization’s database of diagnosis codes. Logs of patients seen in radiation therapy and other outpatient departments are also examined to ensure all cancer patients are identified for inclusion in the registry.

Population-based cancer registries

There are three types of population-based cancer registries. These include incidence only, cancer control, and research. Most incidence-only registries are operated by a government health agency and are designed to determine cancer rates and trends in a defined population. Monitoring cancer incidence is legislatively mandated in most states. The mandate usually outlines the duties of the registry system and the data to be collected, targets the sources from which data are to be obtained, details the confidentiality policies of the system, provides protection from any liability, and in many states defines the penalties for noncompliance. Data collected are typically limited to patient and cancer identification.

Cancer control population-based registries serve a broader function, often combining incidence, patient care, and end results reporting with various other research and cancer control activities, such as cancer screening and smoking cessation programs. Their data set is often the same as that of their reporting hospitals, including treatment and outcome data and incidence-only information.

Many universities operate research-oriented registries to conduct epidemiologic research focused on etiology (study of the causes of disease). Research requirements commonly include rapid case ascertainment so that patients can be identified and contacted as soon as possible after diagnosis. Research data are typically defined and collected on a project-specific basis by an ad hoc mechanism of chart review, patient contact, or some other special procedure. For example, a study of the incidence of cancer in twins may include sibling identification, chart review of a twin with cancer, and patient and family interviews. Another study may be conducted to determine the risk factors of women younger than age 30 years with breast cancer (a population with a low incidence of this disease).

Conversely, a cancer-control type of registry is operated primarily to support the targeting and evaluation of control programs, such as cancer screening for early detection and education. The registry may be limited to specific types of cancer for which distinctive intervention strategies have been established. The data collected are limited to what is needed for an intervention strategy or to evaluate the intervention effect. Data are used to assess areas of high risk, plan education programs, and focus resources aimed at reducing or eliminating the incidence of cancer. Information is shared with public officials and health care providers and often published in medical and research journals.

Many population-based registries are, in effect, combinations of all three types. The legislative mandate and funding sources normally dictate the effort expended in any one particular area—incidence monitoring, research, or cancer control.13

The case definition for cancer registries consists of neoplasms that are to be reported to the registry. The best classification system for developing a reportable list for a cancer registry is based on the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3).14 This publication includes the listing of codes for the anatomical site and the behavior of the tumor. The ACS requires that all tumors with a morphology behavior code of 2 or higher, indicating an in situ or a malignant tumor in the ICD-O-3, be included for approved cancer programs.8 The medical or research staff associated with the registry may request that other cases be included (e.g., nonmalignant meningiomas, villous adenomas of the colon, benign liver tumors).

Central registries that collect data for the states in the United States each have a cancer registry manual that describes the case definition and case eligibility. For example, in New Jersey, all cases of cancer that were diagnosed after October 1, 1978, are reportable. The exceptions to this requirement are localized skin cancers. In addition, benign and borderline tumors of the brain and central nervous system are also reportable.

Cancer registry abstracting

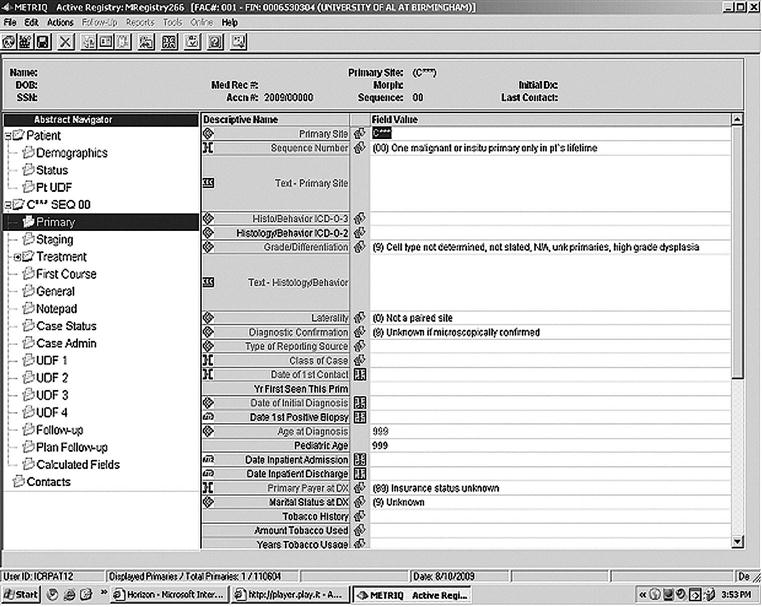

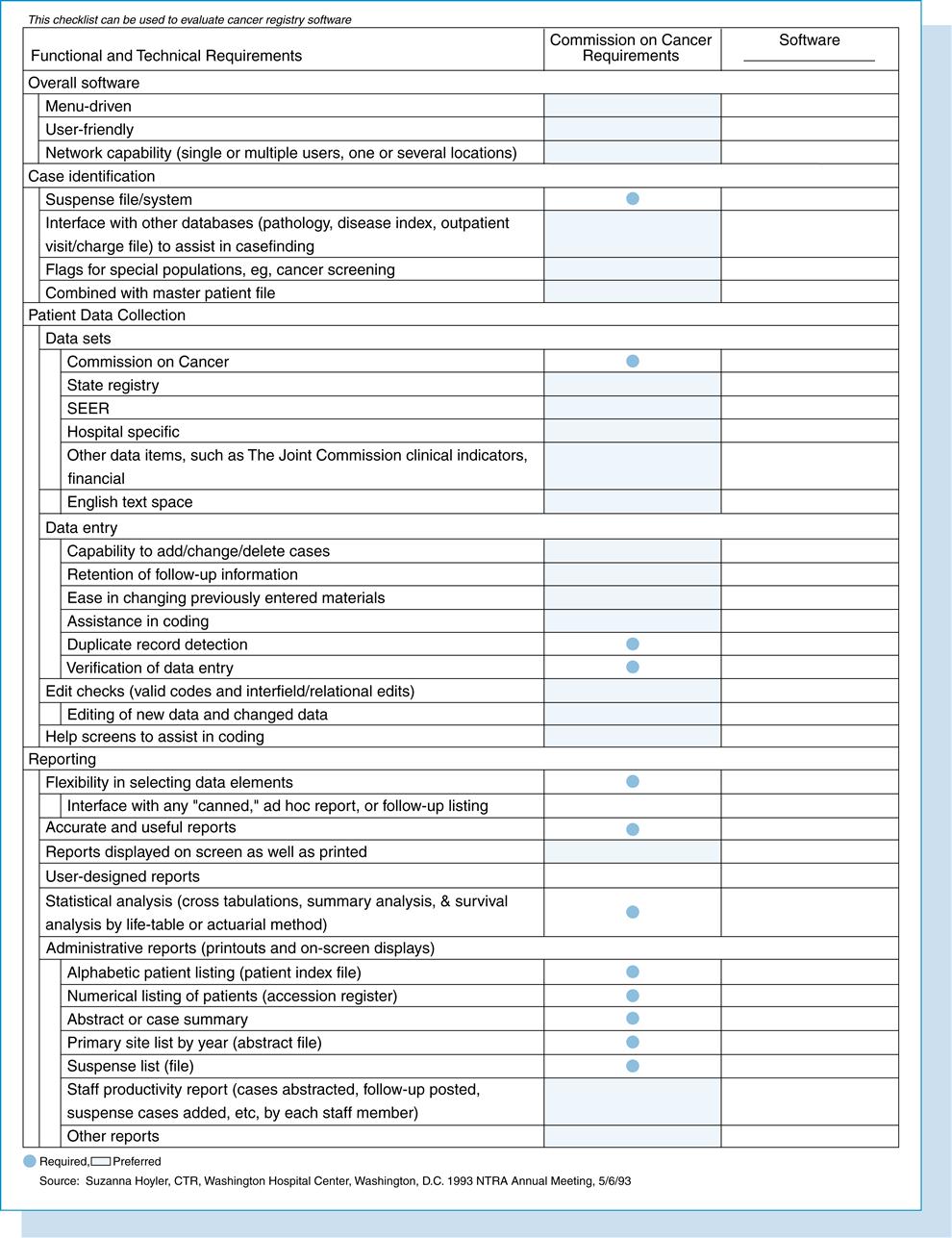

The cancer abstract must permit recording of all relevant data in a logical and uniform manner. Abstracting guidelines are provided in the Self Instructional Manual for Tumor Registrars, Book 5, SEER Program,17 and the Registry Operations and Data Standards (ROADS), CoC, ACS, 2004.16 In addition, most state and regional registries have established abstracting requirements. The amount of data collected is dictated by the CoC for approved cancer programs, policies established by the health care facility’s cancer committee, and the limitations inherent in a specific computer software system (see CoC Data Set). A screen print used in abstracting is shown in Figure 13-3.

Cancer registry coding

The coding scheme traditionally used by cancer registries is the ICD-O-3, published by the World Health Organization (WHO). This coding scheme is recommended by the CoC8 and is used by the National Cancer Registrars Association, Inc. (NCRA) in its annual certification examination.

The ICD-O-3 represents a more detailed extension of the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) chapter on neoplasms. ICD-O-3 permits coding of all neoplasms to include topography (site), morphology (cell structure and form), grading (variation from normal tissue), and differentiation (another term for variation from normal tissue).15

Cancer registry staging

The extent of the spread of cancer or stage at the time of initial diagnosis and treatment is recorded for every case included in the registry.18 Numerous staging systems have been developed for use by the medical community. Some are site-specific (e.g., Dukes A–D Stage Grouping for Colorectal Cancer) or system specific (e.g., International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics [FIGO] classification for gynecologic sites). Others are general and may be applied to almost all sites.

Historically, the staging system most commonly used was developed in 1977 by the SEER Program of the NCI, Self Instructional Manual for Tumor Registrars, Book 6, or the Summary Staging Guide. This system is used to stage cases as in situ, localized, regional spread to lymph nodes or adjacent tissue, or distant spread to lymph nodes in other areas of the body or distant sites. In addition, the CoC requires that all sites, excluding pediatric tumors, be staged according to the current edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Manual for Staging of Cancer.8,19 Registries have the option of using either the AJCC staging scheme for pediatric tumors or nationally accepted protocol staging systems. In the AJCC staging system, the extent of disease is categorized according to tumor size (T), lymph node involvement (N), and metastases (M). Frequently referred to as the TNM system, it brings together information on staging of cancer at various anatomic sites in cooperation with the TNM Committee of the International Union Against Cancer. The proper classification and staging of cancer allow physicians to determine appropriate treatment, evaluate results of case management, and compare outcome with worldwide statistics reported from various institutions on a local, regional, state, and national basis.

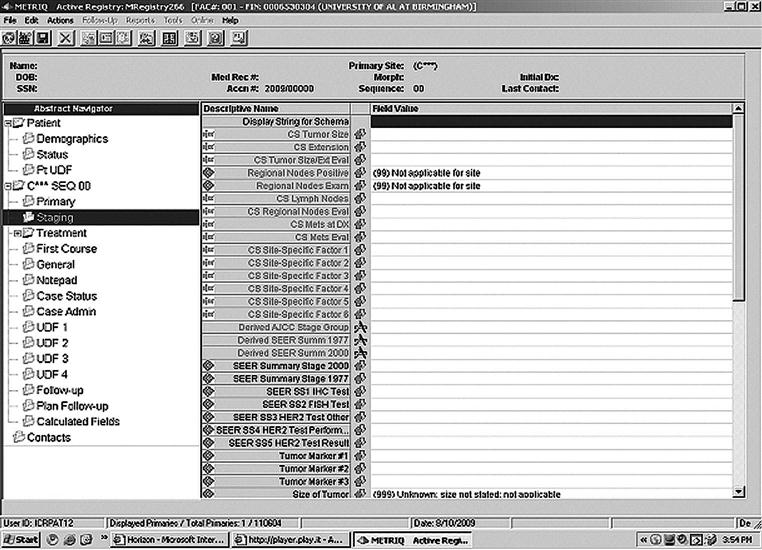

Although the TNM system was designed for use by physicians, in some hospitals, staging is performed by the registry staff.15,20 A working knowledge of both the SEER and the AJCC staging systems is necessary. A patient staging is shown in Figure 13-4.

Figure 13-5 shows the screen print where data from the first course of therapy are entered into the electronic application.

Box 13-1 shows key points regarding staging from NCI.

Quality management of the cancer program and registry data

To be effective, the quality management program must be multidisciplinary and must include four components: quality planning, measurement, evaluation, and improvement. The quality management plan details the roles and responsibilities of the cancer committee and members of the health care team. Some of the outcomes assessed in a quality management program include appropriate and timely diagnosis, appropriate and timely consultations and referrals, accessibility of available health care services, evaluating patient outcomes, and absence of clinically unnecessary diagnostic or therapeutic procedures.

The cancer committee is responsible for establishing the quality improvement priorities of the cancer program and for monitoring the effectiveness of quality improvement activities.8 The cancer committee is required to identify at least two important issues related to cancer patient care to evaluate annually. At least one priority should be related to site-specific patient survival rates. Sources to be used in selecting quality improvement priorities include comparison of local experience with regional and national survival and outcome data. This benchmarking provides insight into whether the care given at the hospital meets or exceeds that given elsewhere. These measures should be used to evaluate compliance with treatment. The cancer committee evaluates the results of the measurement activities to assess current performance and to evaluate the need for interventions aimed at reducing or eliminating poor performance.

The usefulness of the data collected by a registry depends on the quality of the data. Quality control procedures are important to ensure the completeness, accuracy, and timeliness of the data collected. The CoC places accountability for quality control of registry data with the cancer committee because it is responsible for the overall supervision of the cancer registry.8

It is the policy of many registries to perform visual inspection on 100% of their cases. In large registries, a review or reabstracting of a portion of the cases by another member of the registry staff ensures consistent recording and interpretation of information. In the latter instance, the two abstracts are compared, and discrepancies are noted and discussed.15

Computerized registries have quality management tools for edits and computer-assisted coding. Registry staff must not rely solely on the electronic tools for quality management because, as of yet, computers are unable to read the documentation to determine completeness, accuracy, and support for the coded data.

The data collection component encompasses the data items required by the CoC for approved hospital programs. Optional data fields might include hospital-specific, financial, and the Joint Commission clinical indicators. Other features available from some vendors consist of multiple-user networks, hospital mainframe interface, expanded statistical applications, and graphics. Some hospital software vendors maintain national databases that contain aggregate data submitted by their users. The Tumor Registry Software Checklist presented at the 1993 annual meeting of the National Cancer Registrars Association, Inc., can be used by hospitals to evaluate cancer registry software (see Figure 13-6).

The North American Association of Central Cancer Registries, Inc. (NAACCR) has developed a national standard for data exchange. The NAACCR Record Layout provides a common standard record layout that can be used for the electronic exchange of data.21 The NAACCR Record Layout has been used by the ACS Commission on National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) Call for Data. Participation in the NCDB became a mandatory standard of the ACS Approvals Program beginning with the 1996 data year.

Use of cancer registry data

Cancer registry data are used for performance improvement projects, cancer conferences, administrative reports, and marketing. Hospitals with ACS-approved cancer programs are required to publish and distribute an annual report. Approved cancer programs are also required to track the use of cancer registry data.

The cancer registrar profession

The Council on Certification of the NCRA approved the definition of the cancer registry field.

Go to the Evolve Web site to learn more about the NCRA.

Individuals working in or supervising cancer registry and organizations or companies that actively support cancer registration.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree