Research and epidemiology

Valerie J.M. Watzlaf

Objectives

• Explain the vsteps necessary for designing a research study or grant proposal.

• Given a specific hypothesis, design a research study to test the hypothesis.

• Determine the most effective methods to use to test validity and reliability.

• Explain how each epidemiologic research study design can be used in health information management.

Key words

Analytic study

Bias

Case

Case finding

Case studies

Case-control study

Censored

Clinical trial

Close-ended questions

Cohort study

Community trial

Confounding variables

Control

Correlation coefficient

Cross-sectional study

Dependent variable

Descriptive study

Double blind

Epidemiology

Experimental epidemiology

Exposure characteristics

Focus groups

Generalizability

Historical prospective study

Hypothesis

Incidence rate

Incidence study

Incident case

Independent variable

Institutional review board

Interobserver reliability

Intraobserver reliability

Life-table analysis

Literature review

Methodology

Nosocomial

Odds ratio

Open-ended questions

Outcome measures

Participant observation

Peer-reviewed journal

Period prevalence rate

Pilot testing

Point prevalence rate

Prevalence rate

Prevalence study

Prospective study

Qualitative research

Relative risk

Reliability

Research question

Response rate

Retrospective study

Risk factors

Sensitivity

Specific aims

Specificity

Subject blind

Survey design

Triple blind

Validity

Abbreviations

ADL—Activities of Daily Living

AHIMA—American Health Information Management Association

ALOS—Average Length of Stay

ASTM—American Society for Testing and Materials

BMI—Body Mass Index

CAD—Coronary Artery Disease

CAI—Community-Acquired Infection

DRG—Diagnosis-Related Group

EHR—Electronic Health Record

FN—False Negatives

FP—False Positives

HIM—Health Information Management

ICD-9-CM—International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification

IRB—Institutional Review Board

IR—Incidence Rate

JCAHO—Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (now The Joint Commission)

K—Kappa Statistic

NI—Nosocomial Infection

PHR—Personal Health Record

r—Correlation Coefficient

RR—Relative Risk

SPSS—Statistical Process for Social Sciences

TN—True Negatives

TP—True Positives

Student Study Guide activities for this chapter are available on the Evolve Learning Resources site for this textbook. Please visit http://evolve.elsevier.com/Abdelhak.

When you see the Evolve logo  , go to the Evolve site and complete the corresponding activity, referenced by the page number in the text where the logo appears.

, go to the Evolve site and complete the corresponding activity, referenced by the page number in the text where the logo appears.

Epidemiology and health information management (HIM) are two fields that complement each other. Validity and reliability of the data managed by HIM professionals are essential to the soundness and integrity of epidemiologic research studies. The epidemiologic research techniques provide a basis for HIM professionals to take part in designing and conducting research studies that examine several clinical, financial, and administrative areas. Epidemiologic techniques aid the HIM professional not only in conducting clinically based research studies but also in the study of specific HIM department functions, such as whether concurrent coding is more beneficial and cost-effective than coding performed at discharge or whether productivity standards developed for HIM employees are effective.

Because HIM professionals oversee a vast array of health data, it is essential that all epidemiologic methods known to examine these data be used. Epidemiology is the study of disease and the determinants of disease in populations; however, it is also the study of clinical and health care trends or patterns and the ability to recognize trends or patterns within large amounts of data. When HIM professionals master the basic epidemiologic techniques, they become premier detectives seeking out the most prominent, logical, and important trends in the data. This is not an easy task and takes a great deal of practice and thought. However, when the epidemiologic techniques are known, used, and understood, the HIM professional becomes more competent.

Overview of research and epidemiology

Leadership in the field of HIM begins with knowledge. Research provides knowledge. It enables individuals to learn something valuable about their profession. Research also provides new ideas to be shared, new methods and systems to be tried, and new infrastructures to be constructed. The purpose of research is to discover or learn something new about a specific area that was not known before. It enables one to take a question, review the literature related to that question, collect data related to that question, analyze the data collected, and then formulate answers to the question. Research is not formulating answers to your question from your own opinions or perceptions without the collection of new data.

This chapter introduces the reader to research methods and epidemiology. It also includes the types of statistical tests that are most appropriate to use when certain types of epidemiologic studies are conducted. This chapter discusses the relationship between epidemiology and outcomes studies and provides an example of an epidemiologic study that is also a clinical outcomes study. The actual database, methods of data collection and data analysis, and areas of future research are explained and discussed. HIM professionals who are actively involved in analysis, interpretation, and complex research study design should continuously supplement their knowledge through coursework, seminars, and in-service training in these areas as well as work closely with a statistician and an epidemiologist.

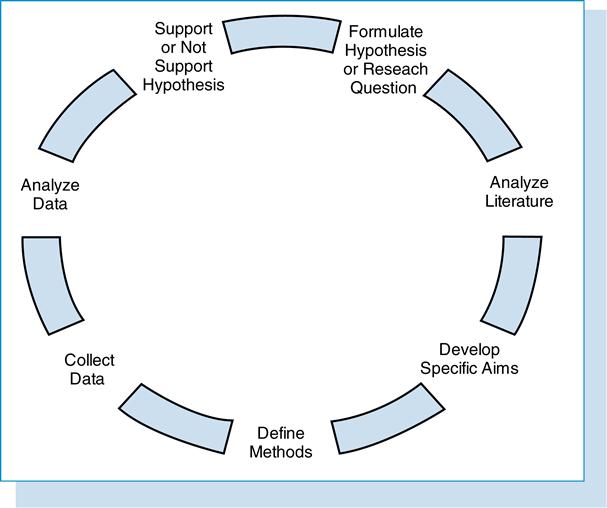

Familiarity with research study protocol (Figure 11-1), including formulating a hypothesis, reviewing and analyzing the literature, developing specific aims, determining the significance of the research, and defining the methodology for collecting and analyzing the data, is necessary for the HIM professional. When the steps of the research design are well formulated and understood, then the data, statistics, and data display are easier to interpret.

Familiarity with the different types of epidemiologic research study designs is necessary to determine whether the health care data generated from a research study are accurate and appropriate. The different epidemiologic research study designs to be examined are the descriptive study (cross-sectional or prevalence), analytic study (case-control or retrospective, cohort or prospective, and historical-prospecive), and experimental study (clinical and community trials). The selection of the study design depends on the hypothesis or research question.

HIM professionals should recognize that every research study involves some degree of bias or error. This may be due to sampling variability, methods of data collection, or confounding variables.

Role of the health information management professional

Medical language and classification expert and domain manager are two roles that are included in the “Report on the Roles and Functions of the e-Health Information Management by the American Health Information Management Association” (AHIMA).1 Do you feel capable of taking on these new roles? Becoming a leader in research in the HIM field and using epidemiologic principles to enhance that research could help you get there.

Becoming a leader in research2 should be a goal of every HIM professional because research leads to advanced knowledge and advanced knowledge leads to advancement of issues that directly affect patient care. The research process can be difficult, and it sometimes takes years before results are established and used. Nevertheless, research enables an individual to test an idea and to determine whether an association between two variables exists. Sometimes this idea has been tossed around for years but, because of priorities given to other aspects of the HIM department, has not been studied. It is important that every HIM professional take the time to perform research on topics that are of interest and relevant to the field.

Healthy People 20103 is a prevention agenda for the nation that identifies the most significant preventable issues related to health and focuses public and private sector efforts to address those issues. It is a comprehensive agenda organized into two major goals that are monitored through 467 objectives in 28 focus areas with 10 leading health indicators. Some of the goals, objectives, and leading health indicators most related to HIM are shown in the following example.

These are national priorities that, when examined through research studies, could make a difference that may affect the world. More specific research goals could also be examined and may include determining the prevalence of specific HIM functions across the country through observation and surveys, determining a national coding accuracy rate, or studying the performance (work) satisfaction levels of HIM employees in different health care settings.

All the areas described are examples of potential research projects. However, choose one that is of great interest to you and proceed. The HIM professional is a leader, and as a leader, he or she should strive to advance the profession. Research provides the avenue for that advancement.

Designing the research proposal

Several steps should be taken when a research or grant proposal is designed that will make the entire process interesting, rewarding, and fulfilling.4 These steps include the following:

1. Identification of a research hypothesis or question

4. Development of the research plan or study design

• Significance and preliminary research

• Experimental design and methods

5. Development of the research budget

Hypothesis and research questions

A hypothesis or research question identifies the goal of the research. The hypothesis is an educated guess about the outcome of the study. It poses an assertion to be supported and may predict a relationship between two or more variables; a research question asks a question to be answered. A hypothesis is not an opinion or value judgment. For example, the statement that every American has the right to health care is a value judgment that cannot be proved right or wrong. Some statements that seem like an opinion on the surface can become a hypothesis with definition of the concepts. The statement “The poor do not have access to health care” can become a testable hypothesis by defining the concept of poor by income level, adequacy by the average in the United States, and health care by the number of physician office visits within a specified period of time. Research questions are used in a new area when not much is known about the topic. Answers to the question will help determine the relationships.5

The concepts in the hypothesis are the variables, which are either independent or dependent. The variable that causes change in the other variables is called an independent variable. A variable for which the value is dependent on one or more other variables but that cannot itself affect the other variables is called a dependent variable. The hypothesized relationship between the variables of interest determines their category. The dependent variable is the variable we wish to explain, and the independent variable is the factor that we believe may explain it. In a causal relationship, the cause is an independent variable and the effect a dependent variable. For example, because smoking causes lung cancer, smoking is an independent variable and lung cancer a dependent variable.5

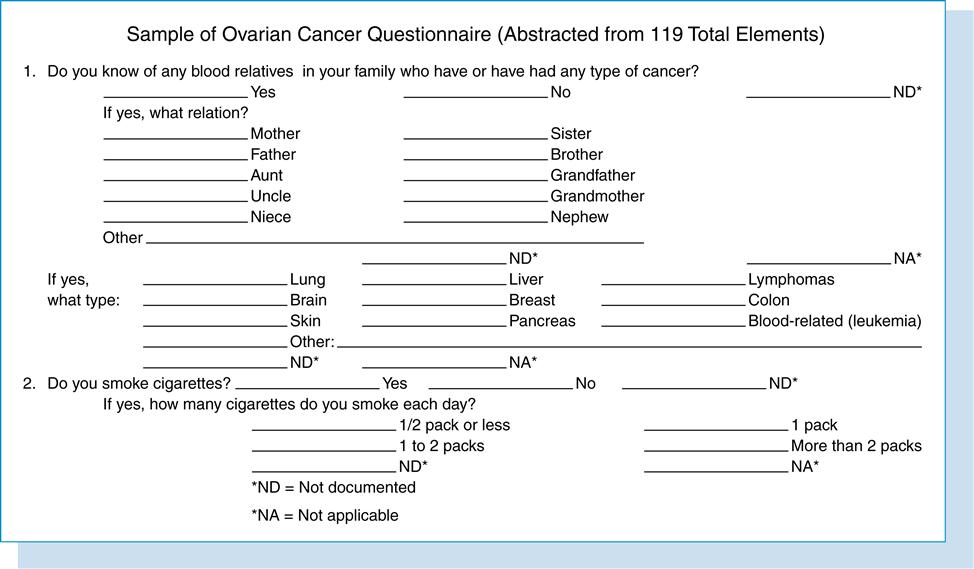

Suppose a researcher wanted to test whether the medical record would prove to be a useful collection tool for factors suspected of being associated with ovarian cancer. Previous research has found that at least 20 factors may be associated with this disease. However, few studies used the medical record alone to collect data pertaining to these factors. Ovarian cancer is a devastating disease that defies early detection. If a link could be made to one or more specific factors, then preventive measures could be taken by women with the factors to decrease the risk of developing ovarian cancer. This study has the following research question:

Is the medical record a useful tool for collecting data pertaining to factors suspected of being associated with ovarian cancer?

and the following hypothesis:

An association exists between risk factors suspected of being linked with ovarian cancer. The ovarian cancer is the dependent variable and the risk factors are the independent variables.

How do you propose an effective hypothesis or research question? Often, a researcher proposes a hypothesis or research question on the basis of ideas that are generated by reading the literature. Other times a researcher has an idea that is generated from personal experiences and then through the review and analysis of the literature develops an insightful hypothesis or research question. Either way, an extensive review of the literature is necessary.

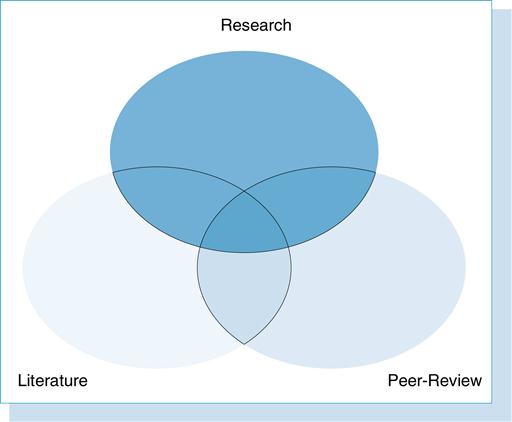

Review of literature

Once the hypothesis or question is established, the second step of a sound research study design is to conduct an extensive literature review (Figure 11-2). A review must be conducted to determine the research that has already been performed in this area. The best way to accomplish this task is to conduct a literature search. Most librarians can conduct a literature search by entering key words and phrases into a computer that then searches through journals, books, and other publications. How far back in time to search must also be specified. A literature search can also be performed independently by searching the Internet or by using other online sources such as MEDLINE. Depending on the type, the search will produce a list that includes the title, author’s name, and journal title and an abstract, if one is available, summarizing each article.

The key words and phrases that are used can make or break the literature search, so they should be chosen with care. If there is uncertainty about which key words to choose, the wording should be discussed with the reference librarian. For example, the key words chosen for the ovarian cancer study included epithelial ovarian cancer, risk factors, epidemiology, and medical record. The Internet is also an excellent resource for conducting the literature search; however, care should be taken because some articles that are found through the Internet may not be peer reviewed (as discussed subsequently). Even so, the Internet can link you to many peer-reviewed articles through MEDLINE, Ovid, and other excellent online searches. Ovid is an international resource of electronic medical, scientific, and academic research information. It supports researchers, students, and others by providing methods on how to search for specific information relevant to a specific research topic.

When the literature search is concluded, it must be carefully examined and any articles of interest should be collected and reviewed. An important step here is to determine whether a particular article is valuable for your research study. For example, the type of journal should be examined. Some journals are peer reviewed, and others are not. Peer reviewed means that peers within the specific research area have extensively reviewed the article and provided comments and feedback to the authors to incorporate into their revision of the article before publication. Some journals, editorials, government reports, and so forth may not be peer reviewed, and although the information in the report may still be important and useful, it did not go through the extensive review process just described.

A critical review of a research article through a peer-review process normally focuses on the following areas:

1. Content is of value, interest, and importance to the reader

2. Hypothesis or research question is clear and appropriate

3. Review of the literature supports the study

4. Study design chosen is appropriate for the hypothesis/research question

5. The methods are appropriate and support the specific aims

6. Statistical analysis is appropriate for the study design

7. The discussion and conclusions are appropriate on the basis of the results

8. Writing, illustrations, tables, and so forth are clear, well organized, and accurate

9. Replication of the methods described could be performed by the reader

It is also important when collecting information for the literature review to distinguish among the citations, references, and bibliographies that are contained in some research articles. Citations provide information about the source of the written material in the body of the article. The citation, which is usually depicted as a number or author’s last name, depending on the style manual used, does not provide much information by itself. You need to go to the reference list or bibliography to get the exact title, author, journal name, and so forth. The reference list is usually at the end of the article and includes only the articles cited within the body of the article. The bibliography is like a list of references; however, it includes additional articles and books not cited in the text but that were reviewed to prepare to write the article and are included for further reading. Therefore, the bibliography may contain many more articles and books than are cited in the article itself.

The purposes of the literature review are:

• To develop a solid foundation in the particular field through study of that topic

• To determine what it is about one’s idea or hypothesis that makes it worth carrying out

Another important task to incorporate into the literature review is to organize all the articles selected into a table that includes the following:

1. Title of the article and journal, book, or report

2. Author(s)

5. Advantages of the article specific to study design for your research topic

By developing a table such as this, the researcher will be better able to determine the gaps of previous research studies and will then know where to focus the research study design.

Methodology (draft)

At this point, the researcher should begin to think about how to design the study so that the hypothesis can be properly tested. The methodology can be the most difficult task and, therefore, should be started as soon as possible. The methodology should include a step-by-step process of what is done in the research study and why this process is necessary to test the hypothesis properly. A rough draft of the methodology should be developed to determine whether the study is feasible. It also allows the researcher to realize how much is known about the subject matter and to think about what the research involves.

Research plan

When a draft of the method has been written and the feasibility of the study confirmed through the literature review, the research plan should be written. It includes the following:

• Significance (review of literature or preliminary research)

• Population under study-sample selection

• Human subjects (if applicable)

Specific aims

The specific aims should briefly describe the project’s goals or objectives. The goals, objectives, aims, or purposes should be enumerated for better clarification. The list should include both short- and long-term goals. For example, the specific aims in the ovarian cancer study are as follows:

Significance (review of literature and preliminary research)

This section should detail the importance of the research project by including a review of past research studies on the same subject (literature review) and preliminary research or pilot studies (if any) performed by the researcher. It should state why the research study must be performed, how it is different from previous research studies, and who the research will benefit. This section should also demonstrate the researcher’s knowledge by including a discussion of existing research that has been performed in the same area and showing the gaps in that research. When these deficiencies are discussed in detail, this part of the plan should reveal how the current research will address these deficiencies.

The key to this section is to be succinct, clear, and organized to convey why the research is important. If the preliminary research is brief, it can be included in the significance section, particularly if it adds to the study’s importance. If the preliminary research is extensive, it should be included in a separate section titled “Preliminary Studies” or “Preliminary Research.”

An excerpt of the significance section is shown in the example to demonstrate how the preliminary research is used to show the importance of the proposed study.

Methodology

The method should include a research design in relation to time, place, and persons. It should consist of the following:

The method should also include a step-by-step plan of how the study is to be performed. This is called the “Procedures” and can include the following:

An excerpt from an actual methodology section is described in the following example.

After the data are collected, a telephone interview will be performed using the pretested data collection instrument to collect any data not found in the medical record and to assess the validity of the data in the medical record.

Analysis of the Data: The data will be entered into a personal computer, and statistical analysis will include frequency distribution, chi-square, and odds ratios. Because the examination of risk factors from medical records may vary from one abstractor to another, various members of the research team will repeat the abstracting of another member, levels of agreement will be determined, and a kappa (κ) statistic will be computed.

Human subjects

The human subjects section is necessary only if human subjects are used in the research or if there are any risks to a human subject. The following should be included in this section:

• How informed consent will be obtained

• If necessary, how confidentiality (risk of privacy) will be safeguarded

• Potential risks and benefits of the study to the people enrolled

Any letters validating IRB approval should be placed in this section to show that the facility where the research will be conducted has approved the study methodology.

Literature referenced

All literature discussed or reviewed in any section of the research proposal should be numbered or cited in that section and a full reference listed at the end of the proposal. Different formats for references are used depending on the preference of the funding agency. Use the format that the funding agency specifies. The general format for a journal reference includes the author(s), year of publication in parentheses, title, name of journal, volume, and page numbers. For a book, it generally includes the author(s), year of publication in parentheses, title, and place and name of publishing company.

Budget development

A detailed budget is necessary to determine the actual costs of the research project and is required for most funding agencies. The budget can include the following:

• Salary and fringe benefits for personnel

• Supplies

• Travel

• Patient care costs, if applicable to the research problem

• Contractual costs, such as including another agency or organization to assist with the study

• Paper

Justification is essential in the budget and should include the specific functions of the personnel, consultants, and collaborators. At times, incentives to study subjects may be necessary to encourage them to participate in the research study. If that is done, the amount of dollars or the specific health care benefit should be listed in the budget as well.

An outline of the budget for the ovarian cancer study if it were carried out today is shown in the example.

Appendix design

The appendix can comprise tables, figures, laboratory tests, data collection forms, and letters of support. It can include anything that is important and relative to the research study or that better clarifies a topic described in the study but that may be too voluminous to include in the body of the proposal. Information such as research articles reviewed or a sample of a database from a preliminary study is not pertinent to the research project and should be excluded. For the ovarian cancer study, the data collection instrument was included in the appendix section of the grant application.

Additional considerations

Most research proposal guidelines have page-length limitations for each of the sections just discussed. It is important to adhere to any page limitations or any other instructions because failure to do this may make the research application ineligible for review by the funding agency.

Validity and reliability

Validity

Validity assesses relevance, completeness, accuracy, and correctness. It measures how well a data collection instrument, laboratory test, medical record abstract, or other data source measures what it should measure. Validity can assess, for example, whether a thermometer truly measures temperature or whether an IQ test really measures intelligence.

It is crucial that the HIM professional be aware of validity problems in specific types of studies. The data collection instrument and the method of data collection have a great impact on the validity of data. To determine whether the validity of a research study is upheld, specific methods should be used. One such method includes gaining confirmatory information from different sources to determine whether the information collected for the study is correct. For example, information recorded in the medical record regarding the patient’s method of payment or insurance carrier can be validated by further examining financial records, physicians’ office records, and pharmacy records. Brief interviews with family members can further confirm or validate the accuracy of correctness of the insurance type.

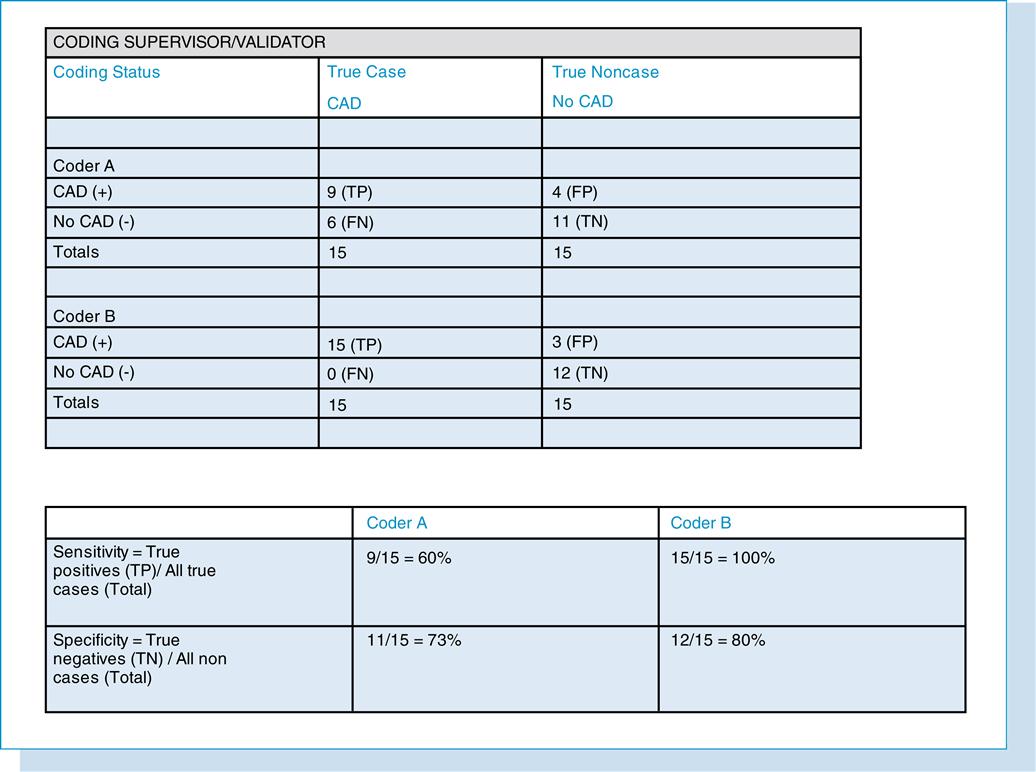

Sensitivity and specificity

Validity also refers to correct measurement or correct labeling. Assessments of methods used to test whether a person has a disease are considered tests of validity regarding the correctness of measurement or labeling. Two measures of this are sensitivity and specificity. To use sensitivity and specificity, one must know the following definitions:

• True positives (TP) correctly categorize true cases as cases—valid labeling.

• False negatives (FN) incorrectly label true cases as noncases—not valid.

• True negatives (TN) correctly label noncases as noncases—valid.

• False positives (FP) incorrectly label noncases as cases—not valid.

Sensitivity is the percentage of all true cases correctly identified—TP/(TP + FN) or TP/Total positives (or total cases).

Specificity is the percentage of all true noncases correctly identified—TN/(TN + FP) or TN/Total negatives (or total noncases).6,7

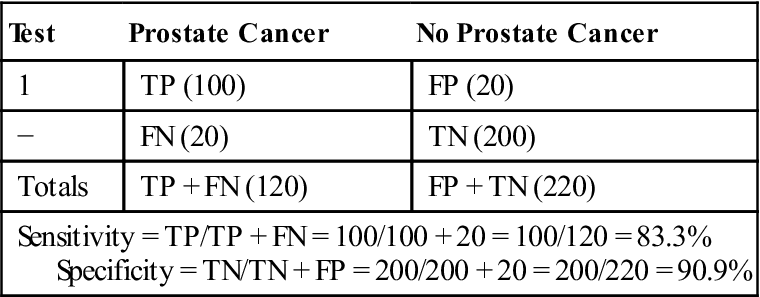

Analysis and discussion

Table 11-1 shows the accuracy of a specific blood test in detecting prostate cancer. The specificity rate of 91% suggests that this blood test correctly labels noncases 91% of the time and misses the noncases 9% of the time. The sensitivity rate of only 83% suggests that the blood test misses 17% of the true cases, or patients with prostate cancer. This blood test could pose serious health problems when true cases may be missed, and therefore diagnosis and treatment may be delayed or missed. Each researcher must determine when the sensitivity and specificity levels are accurate enough to use the test.

Table 11-1

SENSITIVITY AND SPECIFICITY: ACCURACY OF BLOOD TEST TO DETECT PROSTATE CANCER

| Test | Prostate Cancer | No Prostate Cancer |

| 1 | TP (100) | FP (20) |

| − | FN (20) | TN (200) |

| Totals | TP + FN (120) | FP + TN (220) |

| Sensitivity = TP/TP + FN = 100/100 + 20 = 100/120 = 83.3% Specificity = TN/TN + FP = 200/200 + 20 = 200/220 = 90.9% | ||

TP, true positives; FP, false positives; FN, false negatives; TN, true negatives.

Coding validity is a major area of research in the field of HIM. However, there is a paucity of literature in the area of coding accuracy or validity of HIM professionals. Often it is difficult to assess the validity of a principal diagnosis, ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification) code, or diagnosis-related group (DRG) because the basis of the categorization may be subjective. However, the accuracy or validity of coding can be established when a “gold standard” is determined. The gold standard is used as the correct code when conducting research studies. However, one must be aware of the limitations in using such a standard and must strive to lessen the error. The correct diagnosis, code, or DRG can be determined on the basis of coding standards and agreement by expert coders. For example, the validity of coding quality can be determined by having the coding supervisor recode a random sample of records of patients with a principal diagnostic code of coronary artery disease (CAD; Figure 11-4). Two coders—coder A and coder B—did the coding. The recoding performed by the coding supervisor can be considered the gold standard. The validity (sensitivity and specificity) could then be recorded as shown in Figure 11-4. Coder B’s coding is more accurate than coder A’s in accurately coding true cases of CAD (100% vs. 60%) and in accurately coding noncases as noncases (80% vs. 73%).

Specific factors cause incorrect or inaccurate labeling. In the coding example, these factors can include inexperience and lack of knowledge regarding the disease (CAD), ICD-9-CM coding principles, and proper review and analysis of the medical record. Other factors may be related to the equipment, such as outdated coding books. Also, it is obvious that validity is influenced by the gold standard that is selected. When results of such studies are assessed, it is important to consider the subjectivity of the standard.

Reliability

Reliability refers to consistency between users of a given instrument or method. In many research studies, more than one research assistant collects the data. For example, in the ovarian cancer study, an abstract was used to collect the information from the medical records for both cases and controls. Because different research assistants were used to abstract the medical records to collect the data, the classification of the results might differ from one assistant to another. Reproducibility or reliability between more than one research assistant or observer is called interobserver reliability. However, even one individual observer’s response may vary over time. Reliability within one research assistant or observer is called intraobserver reliability.

To test for the reliability of risk factors that were collected from the medical record between research assistants in the ovarian cancer study (described in more detail later in the chapter), each medical record was abstracted three times to determine levels of agreement. Levels of agreement ranged from 71% to 100% for all the characteristics or risk factors collected for the study. A kappa statistic (κ) was also calculated. This statistic enables the researcher to determine whether the agreement levels that are seen are real or are due to the result of chance. A statistic can range from 0.00 to 1.00. A kappa statistic greater than 0.75 equals excellent agreement or reproducibility; 0.4 = κ = 0.75 denotes good agreement; and 0 = κ < 0.4 denotes marginal agreement. After deliberation with our statistician and review of the literature, a statistic of 0.60 was chosen as the standard level for this study; therefore, anything below 0.60 was determined not to be real and caused by chance or sampling variability. Therefore, the usefulness of the agreement levels for those risk factors could be limited.

Another method of testing interobserver reliability when interviewing is to use different research assistants on the first and second interviews of the same subject. One can then measure consistency of recall and variations of response to different research assistants. To measure intraobserver reliability, the same research assistant can be used at different times while measuring consistency of the subject’s response.

Sometimes reliability is measured and reported in the form of a correlation coefficient (r) rather than a proportion or percentage. A correlation coefficient is a statistic that shows the strength of a relationship between two variables. A correlation coefficient, when used to measure degrees of reliability, can range from −1 to +1. The closer r approaches −1 or +1, the stronger the reliability or the relationship between two variables. The closer r approaches zero, the weaker the relationship or reliability.8 For example, if an HIM professional was interested in the correlation between the number of health care providers attending medical record documentation seminars and the number of complete medical records received in the HIM department on discharge of the patient 1 week after the seminar was conducted, a correlation coefficient can be used. A high positive score, such as 0.91, means that as the number of health care providers attending the seminar increased, the number of completed medical records at discharge increased. A high negative score, such as −0.91, means that as the number of health care providers attending the seminar increased, the number of completed medical records decreased.