Introduction to the Laboratory and Safety Training

Objectives

After completing this chapter you should be able to:

Introduction to the Clinical Laboratory

1. List the reasons why laboratory tests are ordered, and describe how specimens are analyzed.

2. Describe the organization and function of medical laboratories.

4. Identify the educational credentials of various personnel who work in laboratories.

5. Describe the necessary attributes required of the laboratory professional.

6. Identify and use laboratory requisitions and reports with proper documentation and confidentiality.

7. Interpret common metric system values used in laboratory test reporting.

Safety Training

3. Identify waste classified as biohazardous, and select appropriate containers for disposal.

4. Describe the proper actions to take after exposure to bloodborne pathogens.

5. List and explain the safety rules that must be observed in the laboratory.

6. Successfully complete a posttest on safety training.

9. Perform a medical hand wash followed by application of PPE and proper removal of PPE.

10. Complete a mock exposure incident report in the workbook appendix.

Key Terms

ambulatory setting outpatient facility versus hospital or bedridden setting

analyte the substance being tested, such as glucose or cholesterol in a blood specimen

biohazard danger related to exposure to infectious and bloodborne pathogens

bloodborne pathogens infectious microorganisms that are transmitted by the blood or bloody body fluid from an infected host into the blood of a susceptible host

Bloodborne Pathogens Standard (BBPS) rigorous standard of policies and procedures developed by OSHA to protect employees who work in occupations where they are at risk of exposure to blood or other potentially infectious materials (i.e., other body fluids that may contain blood)

chemical hazard danger related to exposure to toxic, unstable, explosive, or flammable substances

chronic disorders long-lasting, debilitating conditions

CLIA-waived tests tests that provide simple, unvarying results and require a minimum amount of judgment and interpretation

clinical laboratory a facility or an area within a medical setting in which materials or specimens from the human body are examined or analyzed

coagulation clotting ability of blood

contaminated an area that has been in contact with infectious materials or surfaces where infectious organisms may reside

C-reactive protein (CRP) protein associated with myocardial infarctions (heart attacks)

critical value a test result far from the reference range indicating a threat to a patient’s health (also referred to as “panic value”)

cross-contamination transmitting a pathogen from one individual to another

diabetes mellitus disease caused by the lack of insulin or the inability to regulate blood sugar levels

don to put on

engineering controls efforts and research toward isolating or removing bloodborne pathogens from the workplace (i.e., biohazard disposal containers, safety devices on needles, and sharps containers)

ergonomic practices proper movements and conditions that make a worker less prone to work-related injuries

exposure control plan documented plan provided by a facility to eliminate or minimize occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens

glucose sugar

Hazard Communication Standard federal law protecting employees’ “right to know” about the dangers of all the hazardous chemicals they may be exposed to under normal working conditions

hepatitis A virus (HAV) highly contagious virus that enters the body through the gastrointestinal tract and attacks the liver

hepatitis B virus (HBV) most prevalent bloodborne virus that attacks the liver: an individual can build a protective resistance against this virus by prior immunization or vaccination

hepatitis C virus (HCV) bloodborne virus that attacks the liver and is very likely to reach the chronic stage later in life

homeostasis steady state of internal chemical and physical balance

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) retrovirus that attacks the immune system by destroying the white blood cells known as CD4+ T lymphocytes

laboratory reports results of laboratory tests that have been ordered

laboratory requisitions laboratory orders indicating what tests are to be performed

medical assistants multiskilled professionals dedicated to assisting in patient care management in medical offices, clinics, and ambulatory care centers

nosocomial infection disease spread within a health care facility (also referred to as HCAIs [health care associated infections])

occupational exposure occurs when blood or other potentially infectious material comes in contact with open skin, eye, or mucous membrane or parenterally in the workplace

opportunistic infections infections that occur because of the body’s inability to fight off pathogens normally found in the environment

panels/profiles a series of tests associated with a particular organ or disease

parenteral contact when blood enters the body through the skin or mucous membrane by means of a needle stick, bite, cut, or abrasion

pathogen disease-causing microorganism

patient compliance a patient’s willingness to follow a treatment plan and take an active role in his or her health care

percutaneous through the skin

physical hazards dangers related to electricity, fire, weather emergencies, bomb threats, and accidental injuries

polydipsia excessive thirst

polyphagia excessive hunger

polyuria excessive urination

portal of entry a body opening or break in the skin through which an infectious agent enters the body

portal of exit the route by which an infectious agent leaves the host’s body, such as through the mouth, broken skin, rectum, or body fluids

reagent substance or ingredient used in a laboratory test to detect, measure, examine, or produce a reaction

reference range the range of analyte values with which the general population will consistently show similar results 95% of the time

reservoir host an infected person who is carrying an infectious agent (pathogen)

Standard Precautions CDC recommendations for infection control within health care facilities

susceptible host an individual who is unable to defend herself or himself against a pathogen

transient microorganisms organisms from contaminated objects or infectious patients that adhere to the skin and can be transmitted to others

Universal Precautions assumption that blood or other potentially infectious material from any patient or test kit could be infectious

venipuncture removal of blood from a vein

Abbreviations

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

HCAIs health care associated infections

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

HMIS hazardous materials information system

MSDS material safety data sheets

NFPA National Fire Protective Association

OPIM other potentially infectious material, such as bloody body fluids

OSHA Occupational Safety and Health Administration

PEP postexposure prophylaxis; preventive treatment after exposure to blood or OPIM

POL physician’s office laboratory

PPE personal protective equipment

FUNDAMENTAL CONCEPTS

FUNDAMENTAL CONCEPTS

To enter the investigative world of medical laboratories, a general understanding of the various laboratories that perform medical tests on specimens is needed. Before laboratory procedures can be performed in the ambulatory setting (outpatient facility versus hospital or bedridden setting), a solid foundation is required in laboratory safety issues and government regulations regarding which tests can be performed and how to perform them.

Overview of the Laboratory

The medical laboratory plays a critical role in patient care. This section provides information on the following:

• Why and how laboratory tests are performed

• Where the tests are performed

• How various medical laboratories are organized

• The people involved in the testing process

• The basic terminology and paperwork used in the laboratory

Purpose of Medical Laboratories

A medical or clinical laboratory is defined as a facility or an area within a medical setting in which materials, or specimens, from the human body are examined or analyzed. The results of the various laboratory tests performed on the specimens give the physician a wealth of information regarding the status of the patient or client. Physicians and health care providers use medical laboratories to collect and test specimens for three basic reasons and in three ways.

Why Laboratory Tests Are Ordered

Physicians order laboratory tests for one or more of the following reasons:

3. To monitor the patient’s condition or treatment. Monitoring test results helps the physician keep track of the patient’s specific medical condition or response to treatment on a periodic basis. The following three medical conditions commonly require routine testing to monitor the effects of medication treatments:

• Patients at risk of heart disease who are taking cholesterol-lowering medications are checked periodically for cholesterol levels and liver enzymes. The medication goal is to bring cholesterol levels below 200 and to determine whether the medication is harming the liver, which would raise the blood enzymes ALT and AST (this will be covered in Chapter 6). They may also be tested for C reactive protein (CRP), which is associated with myocardial infarction (heart attack) and indicates the health status of the patient’s cardiovascular system.

Advances in medical instrumentation have allowed the monitoring of all these patients to take place in an ambulatory setting rather than in a hospital or reference laboratory. This allows the physician to see the results immediately, while the patient waits, and then advise the patient accordingly.

Three General Ways to Analyze Specimens

Medical laboratories analyze specimens in the following three basic ways:

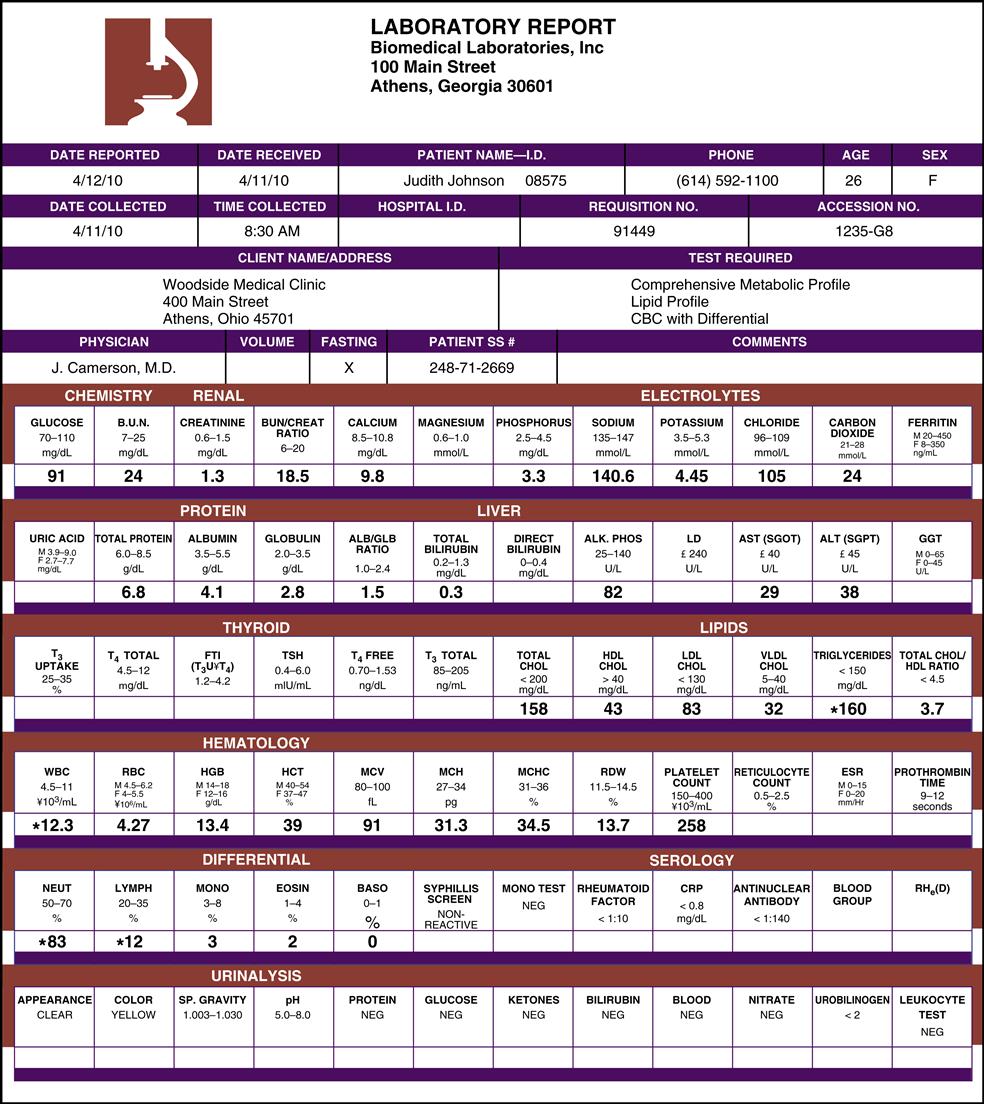

Fig. 1-1 is an example of a reference laboratory’s comprehensive report for blood tests. Note that the reference range for each analyte tested is listed above the patient’s test value. If a test result is far from the reference range, it may be referred to as a critical value or panic value (indicating a threat to a patient’s health). The laboratory report must mark or highlight the critical result requiring immediate attention. In the figure, Judith Johnson does not have any critical values. A variety of laboratory reports (results of laboratory tests that have been ordered) are shown and discussed throughout this text.

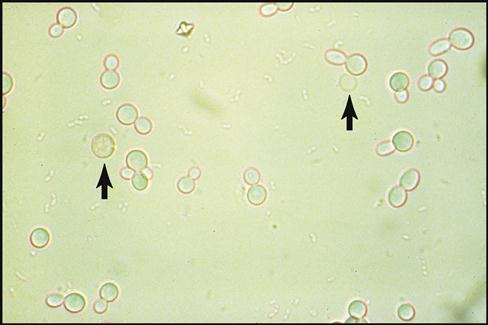

2. Observing and detecting abnormal cells under the microscope. Another way to analyze a specimen is to search for abnormal cells or pathogens (disease-causing microorganisms) under the microscope. In the ambulatory setting this form of testing is generally limited to basic identification of abnormal cells and microorganisms found in urine, blood, or samples taken from infected tissues. Fig. 1-2 shows the abnormal presence of red blood cells and yeast cells in a urine specimen.

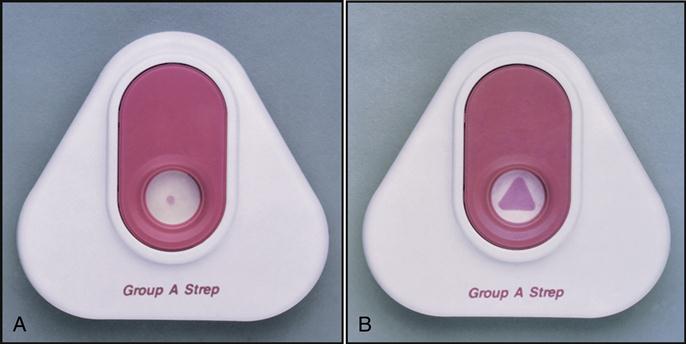

3. Detecting the presence or absence of an infection. The third way to analyze specimens is to test for the presence of pathogens causing an infection. In the ambulatory setting increasing numbers of rapid screening tests are available to help the physician identify the presence of common pathogens. For example, test kits (all components of a test packaged together) are available that can detect the presence of bacteria that cause strep throat, peptic ulcers, and Lyme disease as well as the viruses that cause influenza, mononucleosis, and AIDS. Note the Rapid Strep test results from two throat-swabbed specimens in Fig. 1-3. The left test result is negative for streptococcus A, and the right test is positive for streptococcus A. Further microscopic, chemical, and growth analysis of the pathogen, along with analysis of the pathogen’s sensitivity to antibiotics, is performed by sending the infected swabbed specimen to a microbiology laboratory.

Types of Medical Laboratories and Personnel

The types of medical laboratories range from large, departmentalized institutions to small designated laboratory counters within an ambulatory setting. Personnel in the ambulatory setting interact with staff from all the other types of laboratories and need a basic understanding of how the various laboratories are organized and what types of health care professionals work in each setting.

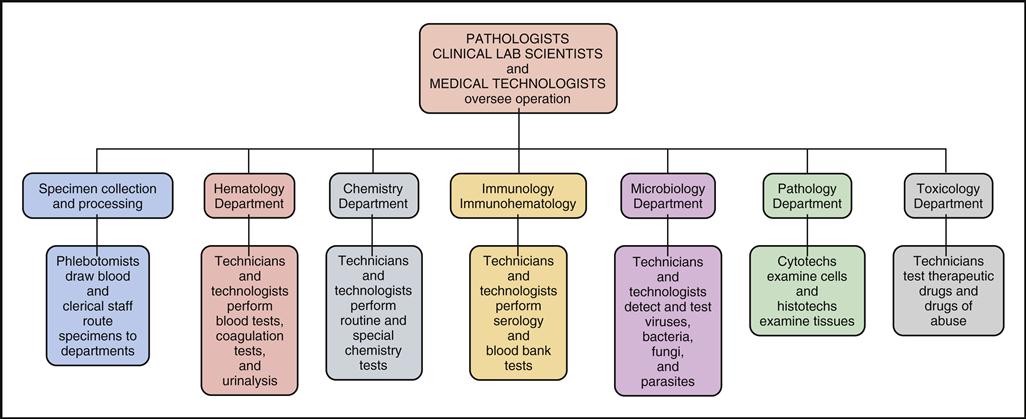

Reference (or Referral) Laboratories

Reference, or referral, laboratories tend to be the largest laboratories, with specialized departments and extensive state-of-the-art equipment. Fig. 1-4 is a sample organizational chart showing the departments typically found in a reference laboratory facility: Specimen Collection and Processing, Hematology, Chemistry, Immunology/Immunohematology, Microbiology, Pathology, and Toxicology.

The reference laboratory is typically staffed with the following trained laboratory professionals:

These teams of laboratory professionals process and evaluate volumes of tests daily and are heavily regulated by the government to ensure that they produce accurate and reliable test results. It is interesting to note that 80% of final definitive diagnoses come from the results of laboratory tests. The testing methods in each department require extensive training in instrument maintenance, problem-solving, test interpretation, and statistical monitoring of test reliability.

Medical offices, health clinics, and hospitals send either their clients or their clients’ specimens along with laboratory requisitions (laboratory orders indicating what tests are to be performed) to the reference lab. Some insurance companies require a specific reference laboratory for their clients. The client’s specimen and requisition must go to the correct reference laboratory for proper insurance reimbursement.

Hospital Laboratories

Hospital laboratories are organized into departments and staffed similarly to reference laboratories. They are involved in diagnostic testing and monitoring the testing of inpatients as well as specimen collection and testing of outpatient specimens from ambulatory settings.

New technology has provided a new approach to patient testing in hospitals called point-of-care testing (POCT). Rather than sending specimens to the laboratory, a testing device can be brought directly to the patient’s bedside and accurate results can be immediately obtained. These user-friendly portable tests are administered by nurses and other health care professionals when a patient’s medical condition, location, or treatment requires immediate results to determine proper medical care. Fig. 1-5 shows a patient’s blood glucose readout of 71 mg/dL on a point-of-care glucometer. Another popular point-of-care instrument is the I-STAT Portable Clinical Analyzer (PCA). It uses disposable cartridges to determine a variety of analytes in whole blood. The analyzer stores up to 50 patient records and permits on-screen viewing of test results. It is capable of transmitting the results to a data management system by using infrared signals. Nonlaboratory hospital personnel must be trained to perform POCT properly.

Ambulatory Care Settings

Unlike the extensive reference laboratories and hospital laboratories, an ambulatory laboratory generally consists of a small, limited space located within a designated area of the physician’s office. Ambulatory care settings generally perform tests that have been designated by the government as CLIA-waived tests (tests that provide simple, unvarying results and require a minimal amount of judgment and interpretation). These government-approved tests provide rapid POCT for screening and monitoring patients in a variety of laboratory areas. The CLIA-waived user-friendly tests most frequently performed in the ambulatory setting that will be presented in this text are the following:

• Routine urinalysis and pregnancy testing

• Basic hematology tests—hemoglobin, hematocrit, sedimentation rate

• Coagulation—prothrombin time and its computed international normalized ratio result

• Immunology/serology—mononucleosis test, Helicobacter pylori test, OraQuick test for HIV

The physician’s office laboratory (POL) has greatly benefited and will continue to benefit from the technical advancements that have improved and simplified so many medical testing methods. A major benefit of POL testing is that ambulatory patients can now obtain their screening and monitoring test results immediately rather than needing to drive to an external laboratory. Also, the physician’s interpretation and therapeutic recommendations can now be given during the same office visit. This has led to better patient care and patient compliance (a patient’s willingness to follow a treatment plan and take an active role in his or her own health care). Many physicians may also perform basic microscopic procedures that have been CLIA approved. NOTE: The CLIA-waived approval process and basic microscopy will be presented in Chapter 2.

Reference and hospital laboratories will continue to provide physicians with the results of the more complex tests. Patient specimens must be sent to these laboratories for the critical test results that provide the doctor with sufficient information to make definitive diagnoses. Because of the complexity of these diagnostic tests, they must be performed by individuals with extensive laboratory training, education, and credentialing. A complete description of such knowledge and training is beyond the scope of this book.

Physician office laboratories are generally staffed by physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and medical assistants. Medical assistants are multiskilled professionals who assist in the patient-care management in medical offices, clinics, and ambulatory care centers. They perform administrative duties and clinical procedures, including the basic CLIA-waived laboratory tests. Medical assistants attend a 1- or 2-year program and are nationally credentialed as CMA (AAMA) or RMA (AMT). There may also be trained laboratory technicians working in the larger POLs that service multiple physicians.

Table 1-1 lists all the health care professionals involved in medical laboratory testing. They are organized by educational credentials, from doctorates to associate degrees and to technical certification. (Nurses are not listed because laboratory training is not part of their education. They are often trained on the job in physicians’ offices.)

TABLE 1-1

Personnel Involved in Laboratory Testing

| Title | Credential | Years of College Training and Degree | Laboratory Setting |

| Board-certified pathologists | MD or DO | 8 or more: doctorate | Reference and hospital laboratories |

| Primary care physicians and specialists | MD or DO or ND (naturopathic doctor) | 6 or more: doctorate | Physician’s office laboratory and health clinics |

| Physician assistants and nurse practitioners | PA, NP | 6 or more: master’s | Physician’s office laboratory and health clinics |

| Clinical laboratory scientist, National Certification Agency for Medical Laboratory Personnel | CLS (NCA) | 4 or more: bachelor’s or master’s | Reference and hospital laboratories |

| Medical technologist, American Society of Clinical Pathologists | MT (ASCP) | 4 or more: bachelor’s | Reference and hospital laboratories |

| Medical technologist, American Medical Technologists | MT (AMT) | 4 or more: bachelor’s | Reference and hospital laboratories |

| Registered medical technologist, International Society for Clinical Laboratory Technology | RMT (ISCLT) | 4 or more: bachelor’s | Reference and hospital laboratories |

| Clinical laboratory technologist, Department of Health and Human Services | CLT (HHS) | 4 or more: bachelor’s | Reference and hospital laboratories |

| Medical laboratory technician, American Society of Clinical Pathologists | MLT (ASCP) ∗ | 2: associate degree | Reference and hospital laboratories and physician’s office laboratories |

| Medical laboratory technician, American Medical Technologists | MLT (AMT) ∗ | 2: associate degree | Reference and hospital laboratories and physician’s office laboratories |

| Clinical laboratory technician, National Certification Agency for Medical Laboratory Personnel | CLT (NCA) ∗ | 2: associate degree | Reference and hospital laboratories and physician’s office laboratories |

| Registered laboratory technician, International Society for Clinical Laboratory Technology | RLT (ISCLT) ∗ | 2: associate degree | Reference and hospital laboratories and physician’s office laboratories |

| Registered phlebotomist | National certification ∗ | 1: technical certificate | All laboratories |

| Certified medical assistant, American Association of Medical Assistants and CAAHEP | CMA (AAMA) ∗ | 1: associate degree or 2: technical certificate | Physician’s office laboratory and ambulatory settings |

| Registered medical assistant, American Medical Technologists | RMA (AMT) ∗ | 1: associate degree or 2: technical certificate | Physician’s office laboratory and ambulatory settings |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree