Drugs for Neurologic Disorders

Parkinsonism and Alzheimer’s Disease

Objectives

• Summarize the pathophysiology of parkinsonism and Alzheimer’s disease.

• Compare the side effects of various antiparkinsonism drugs.

• Apply the nursing process to anticholinergics, dopaminergics, and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.

• Differentiate the phases of Alzheimer’s disease with corresponding symptoms.

Key Terms

acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, p. 322

Alzheimer’s disease, p. 314

bradykinesia, p. 314

dopamine agonists, p. 315

dyskinesia, p. 321

dystonic movement, p. 317

parkinsonism, p. 314

pseudoparkinsonism, p. 315

Parkinsonism (Parkinson’s disease) is a chronic neurologic disorder that affects the extrapyramidal motor tract (which controls posture, balance, and locomotion). It is considered a syndrome (combination of symptoms) because of its three major features: rigidity, bradykinesia (slow movement), and tremors. Rigidity (abnormally increased muscle tone) increases with movement. Postural changes caused by rigidity and bradykinesia include the chest and head thrust forward with the knees and hips flexed, a shuffling gait, and the absence of arm swing. Other characteristic symptoms are masked facies (no facial expression), involuntary tremors of the head and neck, and pill-rolling motions of the hands. The tremors may be more prevalent at rest.

Alzheimer’s disease is a chronic, progressive, neurodegenerative condition with marked cognitive dysfunction. Various theories exist as to the cause of Alzheimer’s disease: neuritic plaques, degeneration of the cholinergic neurons, and deficiency in acetylcholine.

Parkinsonism

In 1817, Dr. James Parkinson described six patients as having “shaking palsy.” Three symptoms were described by Parkinson: (1) involuntary tremors of the limbs, (2) rigidity of muscles, and (3) slowness of movement. In the United States, there are approximately one million persons with parkinsonism, and 50,000 new cases are diagnosed each year. Because parkinsonism generally affects patients 50 years of age and older, many consider the health problem to be part of the aging process caused by loss of neurons. The three cardinal symptoms are rigidity, tremors, and bradykinesia. Normally the symptoms have a gradual onset and are usually mild and unilateral in the beginning.

There are different types of parkinsonism. Pseudoparkinsonism frequently occurs as an adverse reaction to antipsychotic drugs, especially the phenothiazines. In addition, parkinsonism symptoms could result from poisons (e.g., carbon monoxide, manganese), arteriosclerosis, and Wilson’s disease (hepatolenticular degeneration).

Nonpharmacologic Measures

Symptoms of parkinsonism can be lessened through the use of nonpharmacologic measures such as patient teaching, exercise, nutrition, and group support. Exercise can improve mobility and flexibility; the patient with parkinsonism should enroll in a therapeutic exercise program tailored to this disorder. A balanced diet with fiber and fluids helps prevent constipation and weight loss. Patients with parkinsonism and their family members should be encouraged to attend a support group to help cope with and understand this disorder.

Pathophysiology

Parkinsonism is caused by an imbalance of the neurotransmitters dopamine (DA) and acetylcholine (ACh). It is marked by degeneration of neurons of the extrapyramidal motor tract. The reason for the degeneration of neurons is unknown.

There are two neurotransmitters within neurons of the striatum of the brain: dopamine, an inhibitory neurotransmitter, and acetylcholine, an excitatory neurotransmitter. Dopamine is released from the dopaminergic neurons; acetylcholine is released from the cholinergic neurons. Dopamine normally maintains control of acetylcholine and inhibits its excitatory response. In parkinsonism, there is an unexplained degeneration of the dopaminergic neurons, and an imbalance between dopamine and acetylcholine occurs. With less dopamine production, the excitatory response of acetylcholine exceeds the inhibitory response of dopamine. An excessive amount of acetylcholine stimulates neurons that release GABA. With increased stimulation of GABA, the symptomatic movement disorders of parkinsonism occur.

By the time early symptoms of parkinsonism appear, 80% of the striatal dopamine has already been depleted. The remaining striatal neurons synthesize dopamine from levodopa and release dopamine as needed. Before the next dose of levodopa, symptoms (e.g., slow walking, loss of dexterity) return or worsen, but within 30 to 60 minutes of receiving a dose, the patient’s functioning is much improved.

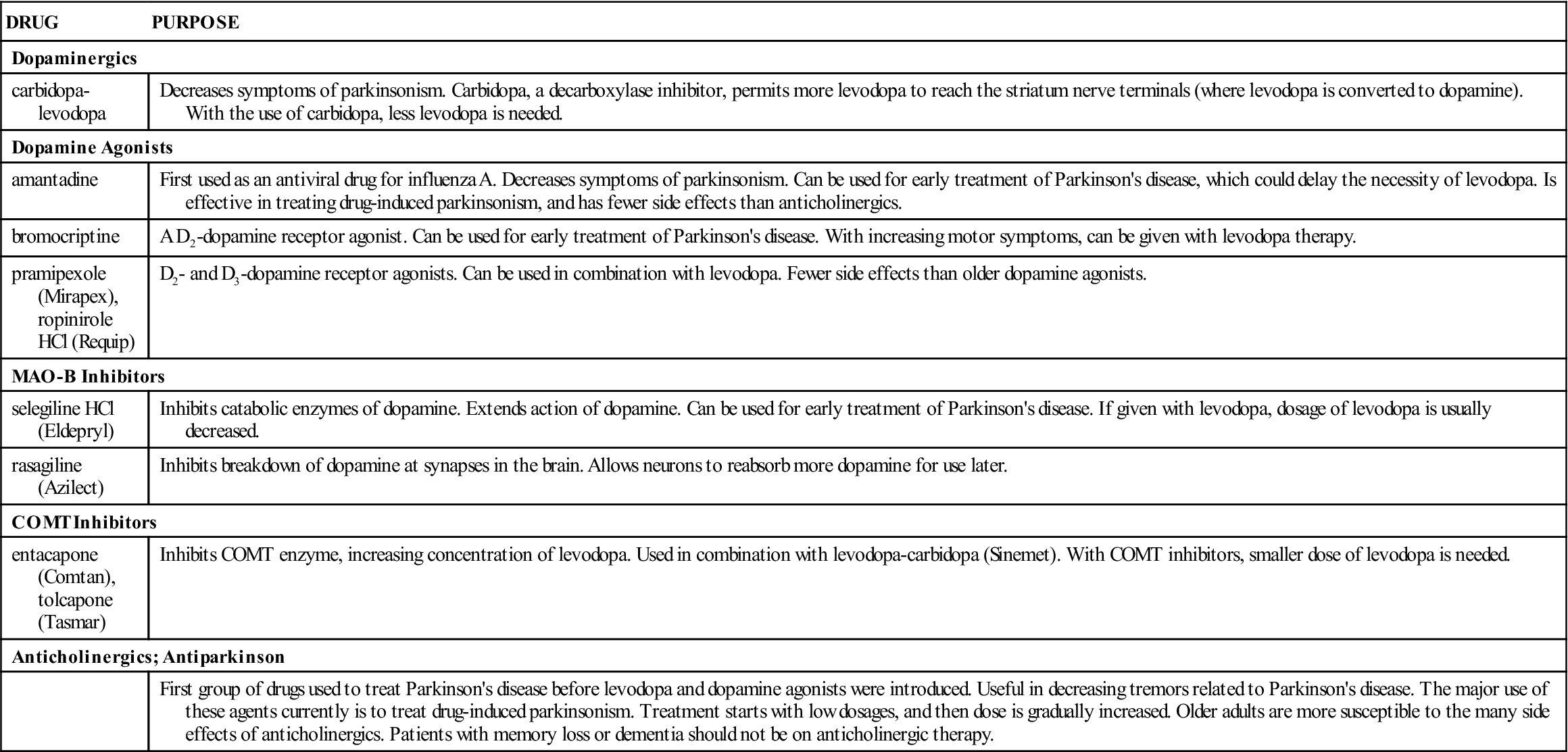

Drugs used to treat parkinsonism reduce the symptoms or replace the dopamine deficit. These drugs fall into five categories: (1) anticholinergics, which block cholinergic receptors; (2) dopamine replacements, which stimulate dopamine receptors; (3) dopamine agonists, which stimulate dopamine receptors; (4) MAO-B inhibitors, which inhibit the monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B) enzyme that interferes with dopamine; and (5) COMT inhibitors, which inhibit the catechol O-methyltransferase enzyme that inactivates dopamine. Table 23-1 compares the various parkinsonism drugs.

TABLE 23-1

COMPARISON OF DRUGS USED TO TREAT PARKINSON’S DISEASE

| DRUG | PURPOSE |

| Dopaminergics | |

| carbidopa-levodopa | Decreases symptoms of parkinsonism. Carbidopa, a decarboxylase inhibitor, permits more levodopa to reach the striatum nerve terminals (where levodopa is converted to dopamine). With the use of carbidopa, less levodopa is needed. |

| Dopamine Agonists | |

| amantadine | First used as an antiviral drug for influenza A. Decreases symptoms of parkinsonism. Can be used for early treatment of Parkinson’s disease, which could delay the necessity of levodopa. Is effective in treating drug-induced parkinsonism, and has fewer side effects than anticholinergics. |

| bromocriptine | A D2-dopamine receptor agonist. Can be used for early treatment of Parkinson’s disease. With increasing motor symptoms, can be given with levodopa therapy. |

| pramipexole (Mirapex), ropinirole HCl (Requip) | D2– and D3-dopamine receptor agonists. Can be used in combination with levodopa. Fewer side effects than older dopamine agonists. |

| MAO-B Inhibitors | |

| selegiline HCl (Eldepryl) | Inhibits catabolic enzymes of dopamine. Extends action of dopamine. Can be used for early treatment of Parkinson’s disease. If given with levodopa, dosage of levodopa is usually decreased. |

| rasagiline (Azilect) | Inhibits breakdown of dopamine at synapses in the brain. Allows neurons to reabsorb more dopamine for use later. |

| COMT Inhibitors | |

| entacapone (Comtan), tolcapone (Tasmar) | Inhibits COMT enzyme, increasing concentration of levodopa. Used in combination with levodopa-carbidopa (Sinemet). With COMT inhibitors, smaller dose of levodopa is needed. |

| Anticholinergics; Antiparkinson | |

| First group of drugs used to treat Parkinson’s disease before levodopa and dopamine agonists were introduced. Useful in decreasing tremors related to Parkinson’s disease. The major use of these agents currently is to treat drug-induced parkinsonism. Treatment starts with low dosages, and then dose is gradually increased. Older adults are more susceptible to the many side effects of anticholinergics. Patients with memory loss or dementia should not be on anticholinergic therapy. | |

COMT, Catechol O-methyltransferase; MAO-B, monoamine oxidase-B.

Anticholinergics

Anticholinergic drugs reduce the rigidity and some of the tremors characteristic of parkinsonism but have minimal effect on bradykinesia. The anticholinergics are parasympatholytics that inhibit the release of acetylcholine. Anticholinergics are still used to treat drug-induced parkinsonism, or pseudoparkinsonism, a side effect of the antipsychotic drug group phenothiazines. Examples of anticholinergics used for parkinsonism include trihexyphenidyl (Artane), benztropine (Cogentin), and biperiden (Akineton).

Diphenhydramine (Benadryl), an antihistamine, has similar anticholinergic properties. It is sometimes used to treat mild parkinsonism and for older adults who may not be able to tolerate the dopamine agonist group of drugs.

Table 23-2 lists the anticholinergics and their dosages, uses, and considerations. Anticholinergics used to treat parkinsonism are also discussed in Chapter 19.

TABLE 23-2

ANTIPARKINSON DRUGS: ANTICHOLINERGICS

| GENERIC (BRAND) | ROUTE AND DOSAGE | USES AND CONSIDERATIONS |

| benztropine mesylate (Cogentin) | Parkinsonism: A: PO/IM: Initially 0.5-1 mg/d h.s. maint: 6 mg/d in 2 divided doses; max: 8 mg/d Extrapyramidal syndrome: A: PO: 1-4 mg q.d./b.i.d. | For parkinsonism and drug-induced parkinsonism to reduce dystonia. May be taken with other antiparkinson drugs. Contraindicated in glaucoma, GI obstruction, severe ulcerative colitis, prostatic hypertrophy, myasthenia gravis. Pregnancy category: C; PB: UK;  : UK : UK |

| biperiden HCl (Akineton) | Parkinsonism: A: PO: 2 mg t.i.d./q.i.d.; max: 16 mg/d EPS: A: PO/IM: 2 mg q.d./b.i.d.; max: 8 mg/d C: IM: 40 mcg/kg, may repeat q30min; max: 4 mg/d | For parkinsonism and drug-induced parkinsonism (EPS). With prolonged use, drug tolerance may occur. Similar contraindications as benztropine. Avoid taking drug with alcohol or CNS depressants. Dry mouth, blurred vision, drowsiness, muscle weakness, and constipation may occur. Pregnancy category: C; PB: UK;  : UK : UK |

| trihexyphenidyl HCl (Artane) | Parkinsonism: A: PO: 1 mg initially, increase by 2 mg q3-5d up to 6-10 mg/d; max: 15 mg/d EPS: A: PO: 1 mg initially, increase to 5-15 mg/d in divided doses | For treating involuntary movement symptoms of parkinsonism and drug-induced pseudoparkinsonism. Does not treat drug-induced tardive dyskinesia. Pregnancy category: C; PB: UK;  : 5-10 h : 5-10 h |

Dopaminergics

Carbidopa and Levodopa

The first dopaminergic drug was levodopa (L-dopa), which was introduced in 1961 but is no longer available in the United States. When introduced, levodopa was effective in diminishing symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and increasing mobility, because the blood-brain barrier admits levodopa but not dopamine. The enzyme dopa decarboxylase converts levodopa to dopamine in the brain, but this enzyme is also found in the peripheral nervous system and allows 99% of levodopa to be converted to dopamine before it reaches the brain. Therefore only about 1% of levodopa taken is available to be converted to dopamine once it reaches the brain, and large doses are needed to achieve a pharmacologic response. These high doses could cause many side effects, including nausea, vomiting, dyskinesia, orthostatic hypotension, cardiac dysrhythmias, and psychosis.

Because of the side effects of levodopa and the fact that so much levodopa is metabolized before reaching the brain, an alternative drug, carbidopa, was developed to inhibit the enzyme dopa decarboxylase. By inhibiting the enzyme in the peripheral nervous system, more levodopa reaches the brain. The carbidopa is combined with levodopa in a ratio of 1 part carbidopa to 10 parts levodopa. Figure 23-1 illustrates the comparative action of levodopa and carbidopa-levodopa.

The advantages of combining levodopa with carbidopa are as follows:

• More dopamine reaches the basal ganglia.

• Smaller doses of levodopa are required to achieve the desired effect.

The disadvantage of the carbidopa-levodopa combination is that with more available levodopa, more side effects may be noted. Side effects may include nausea, vomiting, dystonic movement (involuntary abnormal movement), and psychotic behavior. The peripheral side effects of levodopa are not as prevalent; however, cardiac dysrhythmia, palpitations, and orthostatic hypotension may occur. The carbidopa-levodopa combination is usually not used to treat drug-related pseudoparkinsonism. Prototype Drug Chart 23-1 lists the pharmacologic behavior of carbidopa-levodopa.

, half-life; t.i.d., three times a day; UK, unknown.

, half-life; t.i.d., three times a day; UK, unknown.

: 1-2 h

: 1-2 h