Young and Middle Adults

Objectives

• Discuss developmental theories of young and middle adults.

• List and discuss major life events of young and middle adults and the childbearing family.

• Describe developmental tasks of the young adult, the childbearing family, and the middle adult.

• Discuss the significance of family in the life of the adult.

• Describe normal physical changes in young and middle adulthood and pregnancy.

• Discuss cognitive and psychosocial changes occurring during the adult years.

• Describe health concerns of the young adult, the childbearing family, and the middle adult.

Key Terms

Braxton Hicks contractions, p. 163

Climacteric, p. 164

Doula, p. 159

Infertility, p. 162

Lactation, p. 163

Menopause, p. 164

Millennial generation, p. 157

Prenatal care, p. 163

Puerperium, p. 163

Sandwich generation, p. 164

![]()

Young and middle adulthood is a period of challenges, rewards, and crises. Challenges may include the demands of working and raising families, although there are many rewards with these as well. Adults also face crises such as caring for their aging parents, the possibility of job loss in a changing economic environment, and dealing with their own developmental needs and those of their family members.

Classic works by developmental theorists such as Levinson et al (1978), Diekelmann (1976), Erikson (1963, 1982), and Havighurst (1972) attempted to describe the phases of young and middle adulthood and related developmental tasks (see Chapter 11 for an in-depth discussion of developmental theories).

Traditional masculine roles include providing and protecting. However, these roles are now shared with women. Faced with a societal structure that differs greatly from the norms of 20 or 30 years ago, both men and women are assuming different roles in today’s society. Men were traditionally the primary supporter of the family. Today many women pursue careers and contribute significantly to their families’ incomes. In 2006 60% of women participated in the U.S. labor force and constituted 46% of all U.S. workers in the U.S. labor force. Thirty-eight percent of employed women worked in management or professional and related occupations, 34% worked in sales and office occupations; and another 20% worked in service occupations (Business and Professional Women’s Foundation, 2007). However, according to the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) (2008) workers’ union, women in the United States are paid 77.6 cents for every dollar men receive for comparable work.

Developmental theories provide nurses with a basis for understanding the life events and developmental tasks of the young and middle adult. Patients present challenges to nurses who themselves are often young or middle adults coping with the demands of their respective developmental period. Nurses need to recognize the needs of their patients even if they are not experiencing the same challenges and events.

Young Adults

Young adulthood is the period between the late teens and the mid to late 30s (Edelman and Mandle, 2010). In recent years young adults between the ages of 18 and 29 have been referred to as part of the millennial generation. In 2009 young adults made up approximately 33% of the population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). According to the Pew Research Center (2010), today’s young adults are history’s first “always connected” generation, with digital technology and social media major aspects of their lives. They adapt well to new experiences, are more ethnically and racially diverse than previous generations, and are the least overtly religious American generation in modern times. Young adults increasingly move away from their families of origin, establish career goals, and decide whether to marry or remain single and whether to begin families; however, often these goals may be delayed (e.g., because of the economic recession of recent years).

Physical Changes

The young adult usually completes physical growth by the age of 20. An exception to this is the pregnant or lactating woman. The physical, cognitive, and psychosocial changes and the health concerns of the pregnant woman and the childbearing family are extensive.

Young adults are usually quite active, experience severe illnesses less commonly than older age-groups, tend to ignore physical symptoms, and often postpone seeking health care. Physical characteristics of young adults begin to change as middle age approaches. Unless patients have illnesses, assessment findings are generally within normal limits.

Cognitive Changes

Critical thinking habits increase steadily through the young- and middle-adult years. Formal and informal educational experiences, general life experiences, and occupational opportunities dramatically increase the individual’s conceptual, problem-solving, and motor skills.

Identifying an occupational direction is a major task of young adults. When people know their skills, talents, and personality characteristics, educational preparation and occupational choices are easier and more satisfying. A bachelor’s or associate’s degree is the most significant source of postsecondary education for 12 of the 20 fastest-growing occupations.

An understanding of how adults learn helps you to develop patient education plans (see Chapter 25). Adults enter the teaching-learning situation with a background of unique life experiences, including illness. Therefore always view adults as individuals. Their adherence to regimens such as medications, treatments, or lifestyle changes such as smoking cessation involves decision-making processes. When determining the amount of information that an individual needs to make decisions about the prescribed course of therapy, consider factors that possibly affect the individual’s adherence to the regimen, including educational level, socioeconomic factors, and motivation and desire to learn.

Because young adults are continually evolving and adjusting to changes in the home, workplace, and personal lives, their decision-making processes need to be flexible. The more secure young adults are in their roles, the more flexible and open they are to change. Insecure persons tend to be more rigid in making decisions.

Psychosocial Changes

The emotional health of the young adult is related to the individual’s ability to address and resolve personal and social tasks. The young adult is often caught between wanting to prolong the irresponsibility of adolescence and assume adult commitments. However, certain patterns or trends are relatively predictable. Between the ages of 23 and 28, the person refines self-perception and ability for intimacy. From 29 to 34 the person directs enormous energy toward achievement and mastery of the surrounding world. The years from 35 to 43 are a time of vigorous examination of life goals and relationships. People make changes in personal, social, and occupational areas. Often the stresses of this reexamination results in a “midlife crisis” in which marital partner, lifestyle, and occupation change.

Ethnic and gender factors have a sociological and psychological influence in an adult’s life, and these factors pose a distinct challenge for nursing care. Each person holds culture-bound definitions of health and illness. Nurses and other health professionals bring with them distinct practices for the prevention and treatment of illness. Knowing too little about a patient’s self-perception or beliefs regarding health and illness creates conflict between the nurse and the patient. Changes in the traditional role expectations of both men and women in young and middle adulthood also lead to greater challenges for nursing care. For example, women often continue to work during the childrearing years, and many women struggle with the enormity of balancing three careers: wife, mother, and employee. This is a potential source of stress for the adult working woman. Men are more aware of parental and household responsibilities and find themselves having more responsibilities at home while achieving their own career goals (Fortinash and Holoday Worret, 2008). An understanding of ethnicity, race, and gender differences enables a nurse to provide individualized care (see Chapter 9).

Support from a nurse, access to information, and appropriate referrals provide opportunities for achievement of a patient’s potential. Health is not merely the absence of disease but involves wellness in all human dimensions. The nurse acknowledges the importance of the young adult’s psychosocial needs and needs in all other dimensions. The young adult needs to make decisions concerning career, marriage, and parenthood. Although each person makes these decisions based on individual factors, a nurse needs to understand the general principles involved in these aspects of psychosocial development while assessing the young adult’s psychosocial status.

Lifestyle

Family history of cardiovascular, renal, endocrine, or neoplastic disease increases a young adult’s risk of illness. Your role in health promotion is to identify modifiable factors that increase the young adult’s risk for health problems and provide patient education and support to reduce unhealthy lifestyle behaviors (Sanchez et al., 2009).

A personal lifestyle assessment (see Chapter 6) helps nurses and patients identify habits that increase the risk for cardiac, malignant, pulmonary, renal, or other chronic diseases. The assessment includes general life satisfaction, hobbies, and interests; habits such as diet, sleeping, exercise, sexual habits, and use of caffeine, tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs; home conditions and pets; economics, including type of health insurance; occupational environment, including type of work and exposure to hazardous substances; and physical or mental stress. Military records, including dates and geographical area of assignments, may also be useful in assessing the young adult for risk factors. Prolonged stress from lifestyle choices increases wear and tear on the adaptive capacities of the body. Stress-related diseases such as ulcers, emotional disorders, and infections sometimes occur (see Chapter 37).

Career

A successful vocational adjustment is important in the lives of most men and women. Successful employment not only ensures economic security, but it also leads to friendships, social activities, support, and respect from co-workers.

Two-career families are increasing. The two-career family has benefits and liabilities. In addition to increasing the family’s financial base, the person who works outside the home is able to expand friendships, activities, and interests. However, stress exists in a two-career family as well. These stressors result from a transfer to a new city; increased expenditures of physical, mental, or emotional energy; child care demands; or household needs. To avoid stress in a two-career family, partners should share all responsibilities. For example, some families may decide to limit recreational expenses and instead hire someone to do routine housework. Others set up an equal division of household, shopping, and cooking duties.

Sexuality

The development of secondary sex characteristics occurs during the adolescent years (see Chapter 12). Physical development is accompanied by the ability to perform sex acts. The young adult usually has emotional maturity to complement the physical ability and therefore is able to develop mature sexual relationships and establish intimacy. Young adults who have failed to achieve the developmental task of personal integration sometimes develop relationships that are superficial and stereotyped (Fortinash and Holoday Worret, 2008).

Masters and Johnson (1970) contributed important information about the physiological characteristics of the adult sexual response (see Chapter 34). The psychodynamic aspect of sexual activity is as important as the type or frequency of sexual intercourse to young adults. To maintain total wellness, encourage adults to explore various aspects of their sexuality and be aware that their sexual needs and concerns change. As the rate of early initiation of sexual intercourse continues to increase, young adults are at risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Consequently there is an increased need for education regarding the mode of transmission, prevention, and symptom recognition and management for STIs.

Childbearing Cycle

Conception, pregnancy, birth, and the puerperium are major phases of the childbearing cycle. The changes during these phases are complex. Education such as Lamaze classes can prepare pregnant women, their partners, and other support persons to participate in the birthing process (Fig. 13-1). A current trend in some health care agencies is to provide either professional labor support (Sauls, 2006) or a lay doula, a support person to be present during labor to assist women who have no other source of support (Campbell et al., 2006). The stress that many women experience after childbirth has a significant impact on postpartum women’s health (Box 13-1).

Types of Families

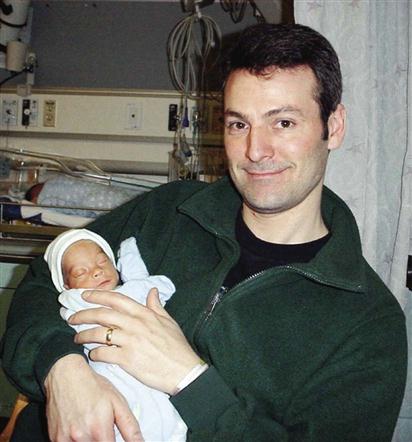

During young adulthood most individuals experience singlehood and the opportunity to be on their own. Those who eventually marry encounter several changes as they take on new responsibilities. For example, many married couples choose to become parents (Fig. 13-2). Some young adults choose alternative lifestyles. Chapter 10 reviews forms of families.

Singlehood

Social pressure to get married is not as great as it once was, and many young adults do not marry until their late 20s or early 30s or not at all. For young adults who remain single, parents and siblings become the nucleus for a family. Some view close friends and associates as “family.” One cause for the increased single population is the expanding career opportunities for women. Women enter the job market with greater career potential and have greater opportunities for financial independence. More single individuals are choosing to live together outside of marriage and become parents either biologically or through adoption. Similarly many married couples choose to separate or divorce if they find their marital situation unsatisfactory.

Parenthood

The availability of contraception makes it easier for today’s couples to decide when and if to start a family. Social pressures may encourage a couple to have a child or influence them to limit the number of children they have. Economic considerations frequently enter into the decision-making process because of the expense of childrearing. General health status and age are also considerations in decisions about parenthood because couples are getting married later and postponing pregnancies, which often results in smaller families.

Alternative Family Structures and Parenting

Changing norms and values about family life in the United States reveal basic shifts in attitudes about family structure. The trend toward greater acceptance of cohabitation without marriage is a factor in the greater numbers of infants being born to single women. In addition, approximately 1.5 million parents are gay or lesbian. More than one third of lesbians have given birth, and one in six gay men have fathered or adopted a child. Gay and lesbian parents are raising 3% of foster children in the United States (Gates et al., 2007). The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), in recognizing the needs of gay and lesbian parents and their children, published a policy statement supporting adoption of children and the parenting role by same-sex parents (AAP, 2002). However, many times parents from alternative family structures still feel a lack of support and even bias from the health care system (Makadon, 2006; McManus et al., 2006).

Hallmarks of Emotional Health

Most young adults have the physical and emotional resources and support systems to meet the many challenges, tasks, and responsibilities they face. During psychosocial assessment of young adults, assess for 10 hallmarks of emotional health (Box 13-2) that indicate successful maturation in this developmental stage.

Health Risks

Health risk factors for a young adult originate in the community, lifestyle patterns, and family history. The lifestyle habits that activate the stress response (see Chapter 37) increase the risk of illness. Smoking is a well-documented risk factor for pulmonary, cardiac, and vascular diseases in smokers and the individuals who receive secondhand smoke. Inhaled cigarette pollutants increase the risk of lung cancer, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis. The nicotine in tobacco is a vasoconstrictor that acts on the coronary arteries, increasing the risk of angina, myocardial infarction, and coronary artery disease. Nicotine also causes peripheral vasoconstriction and leads to vascular problems.

Family History

A family history of a disease puts a young adult at risk for developing it in the middle or older adult years. For example, a young man whose father and paternal grandfather had myocardial infarctions (heart attacks) in their 50s has a risk for a future myocardial infarction. The presence of certain chronic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus in the family increases the family member’s risk of developing a disease. Regular physical examinations and screening are necessary at this stage of development.

Personal Hygiene Habits

As in all age-groups, personal hygiene habits in the young adult are risk factors. Sharing eating utensils with a person who has a contagious illness increases the risk of illness. Poor dental hygiene increases the risk of periodontal disease. Individuals avoid gingivitis (inflammation of the gums) and periodontitis (loss of tooth support) through oral hygiene (see Chapter 39).

Violent Death and Injury

Violence is a common cause of mortality and morbidity in the young-adult population. Factors that predispose individuals to violence, injury, or death include poverty, family breakdown, child abuse and neglect, drug involvement (dealing or illegal use), repeated exposure to violence, and ready access to guns. It is important for the nurse to perform a thorough psychosocial assessment, including such factors as behavior patterns, history of physical and substance abuse, education, work history, and social support systems to detect personal and environmental risk factors for violence. Death and injury occur from physical assaults, motor vehicle or other accidents, and suicide attempts. In 2007, homicides occurred at a higher rate among men and people ages 20 to 24 years than other violent deaths (USDHHS, CDC, 2010a).

Intimate partner violence (IPV), formerly referred to as domestic violence, is a global public health problem. It exists along a continuum from a single episode of violence to ongoing battering (USDHHS, CDC, 2009a). IPV often begins with emotional or mental abuse and may progress to physical or sexual assault. Each year women in the United States experience approximately 4.8 million intimate partner–related physical assaults and rapes, and men are the victims of approximately 2.9 intimate partner–related physical assaults. Physical injuries from IPV range from minor cuts and bruises to broken bones, internal bleeding, and head trauma. IPV is linked to such harmful health behaviors as smoking, alcohol abuse, drug use, and risky sexual activity. Risk factors for the perpetration of IPV include using drugs or alcohol, especially drinking heavily; unemployment; low self-esteem; antisocial or borderline personality traits; desire for power and control in relationships; and being a victim of physical or psychological abuse (El-Bassel et al., 2007; Gil-Gonzalez et al., 2008). The greatest risk of violence occurs during the reproductive years. A pregnant woman has a 35.6% greater risk of being a victim of IPV than a nonpregnant woman. Women experiencing IPV may be more likely to delay prenatal care and are at increased risk for multiple poor maternal and infant health outcomes such as low maternal weight gain, infections, high blood pressure, vaginal bleeding, and delivery of a preterm or low-birth-weight infant (NACCHO, 2008).

Substance Abuse

Substance abuse directly or indirectly contributes to mortality and morbidity in young adults. Intoxicated young adults are often severely injured in motor vehicle accidents, resulting in death or permanent disability to other young adults as well.

Dependence on stimulant or depressant drugs sometimes results in death. Overdose of a stimulant drug (“upper”) stresses the cardiovascular and nervous systems to the extent that death occurs. The use of depressants (“downers”) leads to an accidental or intentional overdose and death.

Caffeine is a naturally occurring legal stimulant that is readily available in carbonated beverages; chocolate-containing foods; coffee and tea; and over-the-counter medications such as cold tablets, allergy and analgesic preparations, and appetite suppressants. It is the most widely ingested stimulant in North America. Caffeine stimulates catecholamine release, which in turn stimulates the central nervous system; it also increases gastric acid secretion, heart rate, and basal metabolic rate. This alters blood pressure, increases diuresis, and relaxes smooth muscle. Consumption of large amounts of caffeine results in restlessness, anxiety, irritability, agitation, muscle tremor, sensory disturbances, heart palpitations, nausea or vomiting, and diarrhea in some individuals.

Substance abuse is not always diagnosable, particularly in its early stages. Nonjudgmental questions about use of legal drugs (prescribed drugs, tobacco, and alcohol), soft drugs (marijuana), and more problematic drugs (cocaine or heroin) are a routine part of any health assessment. Obtain important information by making specific inquiries about past medical problems, changes in food intake or sleep patterns, or problems of emotional lability. Reports of arrests because of driving while intoxicated, wife or child abuse, or disorderly conduct are reasons to investigate the possibility of drug abuse more carefully.

Unplanned Pregnancies

Unplanned pregnancies are a continued source of stress that may result in adverse health outcomes for the mother, infant, and family. Often young adults have educational and career goals that take precedence over family development. Interference with these goals affects future relationships and parent-child relationships.

Determination of situational factors that affect the progress and outcome of an unplanned pregnancy is important. Exploration of problems such as financial, career, and living accommodations; family support systems; potential parenting disorders; depression; and coping mechanisms is important in assessing the woman with an unplanned pregnancy.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

STIs are a major health problem in young adults. Examples of STIs include syphilis, chlamydia, gonorrhea, genital herpes, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). STIs have immediate physical effects such as genital discharge, discomfort, and infection. They also lead to chronic disorders, infertility, or even death. They remain a major public health problem for sexually active people, with almost half of all new infections occurring in men and women younger than 24 years of age (USDHHS, CDC, 2009b). In 2008 20- to 24-year-old men had the highest rate of chlamydia among men (1056.1 per 100,000 population); chlamydia rates in men of this age-group increased by 12.6% from the previous year.

Environmental or Occupational Factors

A common environmental or occupational risk factor is exposure to work-related hazards or agents that cause diseases and cancer (Table 13-1). Examples include lung diseases such as silicosis from inhalation of talcum and silicon dust and emphysema from inhalation of smoke. Cancers resulting from occupational exposures may involve the lung, liver, brain, blood, or skin. Questions regarding occupational exposure to hazardous materials should be a routine part of your assessment.

TABLE 13-1

Occupational Hazards/Exposures Associated with Diseases and Cancers

| JOB CATEGORY | OCCUPATIONAL HAZARD/EXPOSURE | WORK-RELATED CONDITION/CANCER |

| Agricultural workers | Pesticides, infectious agents, gases, sunlight | Pesticide poisoning, “farmer’s lung,” skin cancer |

| Anesthetists | Anesthetic gases | Reproductive effects, cancer |

| Automobile workers | Asbestos, plastics, lead, solvents | Asbestosis, dermatitis |

| Carpenters | Wood dust, wood preservatives, adhesives | Nasopharyngeal cancer, dermatitis |

| Cement workers | Cement dust, metals | Dermatitis, bronchitis |

| Dry cleaners | Solvents | Liver disease, dermatitis |

| Dye workers | Dyestuffs, metals, solvents | Bladder cancer, dermatitis |

| Glass workers | Heat, solvents, metal powders | Cataracts |

| Hospital workers | Infectious agents, cleansers, latex gloves, radiation | Infections, latex allergies, unintentional injuries |

| Insulators | Asbestos, fibrous glass | Asbestosis, lung cancer, mesothelioma |

| Jackhammer operators | Vibration | Raynaud’s phenomenon |

| Lathe operators | Metal dusts, cutting oils | Lung disease, cancer |

| Office computer workers | Repetitive wrist motion on computers; eyestrain | Tendonitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, tenosynovitis |

From Stanhope M, Lancaster J: Foundations of nursing in the community, ed 3, St Louis, 2010, Mosby.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree