Care of Surgical Patients

Objectives

• Explain the concept of perioperative nursing care.

• Differentiate among classifications of surgery and types of anesthesia.

• Describe the assessment data to collect for a surgical patient.

• Design a preoperative teaching plan.

• Prepare a patient for surgery.

• Explain the nurse’s role in the operating room.

• Describe the rationale for nursing interventions designed to prevent postoperative complications.

Key Terms

Ambulatory surgery, p. 1255

American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), p. 1255

American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses (ASPAN), p. 1255

Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN), p. 1255

Atelectasis, p. 1260

Bariatric, p. 1260

Cholecystectomy, p. 1255

Circulating nurse, p. 1271

Conscious sedation, p. 1273

General anesthesia, p. 1272

Graded compression stockings, p. 1272

Informed consent, p. 1267

Laparoscopic, p. 1255

Latex sensitivity, p. 1272

Local anesthesia, p. 1273

Malignant hyperthermia, p. 1278

Moribund, p. 1256

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), p. 1260

Paralytic ileus, p. 1279

Perioperative nursing, p. 1254

Postanesthesia recovery score (PARS), p. 1275

Postanesthesia recovery score for ambulatory patients (PARSAP), p. 1276

Preoperative teaching plan, p. 1265

Regional anesthesia, p. 1273

Scrub nurse, p. 1271

![]()

Perioperative nursing care is nursing care given before (preoperative), during (intraoperative), and after (postoperative) surgery. It takes place in hospitals, surgical centers attached to hospitals, freestanding surgical centers, or health care providers’ offices. Perioperative nursing is a fast-paced, changing, and challenging field. It is based on the nurse’s understanding of several important principles, including:

• High-quality and patient safety–focused care.

• Effective and efficient assessment and intervention in all phases of surgery.

• Advocacy for the patient and the patient’s family.

When you work in a perioperative setting, you need to practice strict surgical asepsis, thoroughly document care, and emphasize patient safety in all phases of care. Effective teaching and discharge planning prevent or minimize complications and ensure quality outcomes. The nursing process provides a basis for perioperative nursing, with the nurse individualizing strategies throughout the perioperative period so the patient has a smooth course from admission into the health care system through convalescence. Continuity of care is stressed in the perioperative model.

Care of the patient having surgery has shifted from hospital-based to home-based convalescence, with responsibility shifting to the patient and/or family. As the length of hospital stay decreases, the educational needs of the patient undergoing a surgical procedure increase. Patients return home with complex medical/surgical conditions that require both education and follow-up. Proper patient education is essential to ensuring positive surgical outcomes.

History of Surgical Nursing

The discipline of surgery progressed as a science in the twentieth century to give physicians the means to treat conditions that were difficult or impossible to manage with medicine alone. In 1956 the Association of Operating Room Nurses (AORN) was formed to gain knowledge of surgical principles and explore methods to improve nursing care of surgical patients. The organization is now known as the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses; however, AORN is still its acronym. AORN is the driving force for the practice of perioperative nursing and has developed standards of nursing practice that outline the scope of responsibility of the perioperative nurse. It was the first nursing organization to develop structure, process, and outcome standards as defined by the American Nurses Association (ANA). Current standards of perioperative professional practice include a patient-centered model of care with focus on (1) clinical practice, (2) professional practice, (3) administrative practice, (4) patient outcomes, and (5) quality improvement (AORN, 2011).

Ambulatory Surgery

During the 1970s the advent of ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs), also referred to as outpatient surgery, short-stay surgery, or same-day surgery, changed the perioperative process. Centers providing these services are hospital-based or freestanding surgical centers. Starting in 1982 Medicare began paying for surgeries performed in ASCs, and now over half of all elective surgical procedures occur on an outpatient basis. This increase is the result of payer changes and advances in medical technology. These procedures include ophthalmic, gastroenterological, gynecological, eye-ear-nose-throat, orthopedic, cosmetic/restorative, and general (Ambulatory Surgery Center Association, 2010). Many patients are discharged the day of surgery following reversal of the anesthetic agent. One-day surgery, in which the patient is admitted the day of surgery and observed overnight (23-hour admission), also occurs.

There are benefits for the patient who has ambulatory surgery. Anesthetic drugs that metabolize rapidly with few aftereffects allow shorter operative times and faster recovery time. Ambulatory surgery also offers cost savings by eliminating the need for hospital stays, thus reducing the possibility of acquiring health care–associated infections (HAIs). For example, many abdominal procedures such as gallbladder removal (cholecystectomy) are now performed using laparoscopic procedures. Laparoscopic surgery involves the use of minimally invasive techniques with small incisions and cameras or scopes for performance of the surgery as opposed to a large incision required for an open surgery. Because of the small incision, a laparoscopic cholecystectomy involves only a few hours to a 24-hour hospital stay and a recovery period of a week. By contrast, an open cholecystectomy involves a larger abdominal incision with a hospitalization of 1 to 3 days and up to a 4-week recovery period. Advances in medical technology have made laparoscopic procedures more commonplace and less risky. Thus many surgeons use them instead of traditional surgical procedures, thereby decreasing the length of surgery, hospitalization, and associated costs.

Scientific Knowledge Base

Classification of Surgery

The types of surgical procedures are classified according to seriousness, urgency, and purpose (Table 50-1). Some procedures fall into more than one classification. For example, surgical removal of a disfiguring scar is minor in seriousness, elective in urgency, and reconstructive in purpose. Frequently the classes overlap. An urgent procedure is also major in seriousness. Sometimes the same operation is performed for different reasons on different patients. For example, a gastrectomy may be performed as an emergency procedure to resect a bleeding ulcer or as an urgent procedure to remove a cancerous growth. The classification indicates the level of care a patient requires. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) assigns classification based on a patient’s physiological condition independent of the proposed surgical procedure (Table 50-2). Anesthesia always involves risks even in healthy patients, but certain patients are at higher risk, including those who are volume depleted or who have poor cardiac function (Rothrock, 2007). ASA physical status classes 1 and 2 and also stable class 3 are now acceptable for ambulatory surgery. Classes 4 and 5 require inpatient surgery.

TABLE 50-1

Classification of Surgical Procedures

| TYPE | DESCRIPTION | EXAMPLE |

| Seriousness | ||

| Major | Involves extensive reconstruction or alteration in body parts; poses great risks to well-being | Coronary artery bypass, colon resection, removal of larynx, resection of lung lobe |

| Minor | Involves minimal alteration in body parts; often designed to correct deformities; involves minimal risks compared with major procedures | Cataract extraction, facial plastic surgery, tooth extraction |

| Urgency | ||

| Elective | Performed on basis of patient’s choice; is not essential and is not always necessary for health | Bunionectomy, facial plastic surgery, hernia repair, breast reconstruction |

| Urgent | Necessary for patient’s health; often prevents additional problems from developing (e.g., tissue destruction or impaired organ function); not necessarily emergency | Excision of cancerous tumor, removal of gallbladder for stones, vascular repair for obstructed artery (e.g., coronary artery bypass) |

| Emergency | Must be done immediately to save life or preserve function of body part | Repair of perforated appendix or traumatic amputation, control of internal hemorrhaging |

| Purpose | ||

| Diagnostic | Surgical exploration that allows health care providers to confirm diagnosis; often involves removal of tissue for further diagnostic testing | Exploratory laparotomy (incision into peritoneal cavity to inspect abdominal organs), breast mass biopsy |

| Ablative | Excision or removal of diseased body part | Amputation, removal of appendix, cholecystectomy |

| Palliative | Relieves or reduces intensity of disease symptoms; does not produce cure | Colostomy, debridement of necrotic tissue, resection of nerve roots |

| Reconstructive/restorative | Restores function or appearance to traumatized or malfunctioning tissues | Internal fixation of fractures, scar revision |

| Procurement for transplant | Removal of organs and/or tissues from a person pronounced brain dead for transplantation into another person | Kidney, heart, or liver transplant |

| Constructive | Restores function lost or reduced as result of congenital anomalies | Repair of cleft palate, closure of atrial septal defect in heart |

| Cosmetic | Performed to improve personal appearance | Blepharoplasty for eyelid deformities; rhinoplasty to reshape nose |

TABLE 50-2

Physical Status (PS) Classification of the American Society of Anesthesiologists

| CLASS | DESCRIPTION | CHARACTERISTICS |

| P1 | A normal healthy patient | No physiological, biological, organic disturbance |

| P2 | A patient with mild systemic disease | Cardiovascular (CV) disease with minimal restriction on activity |

| P3 | A patient with severe systemic disease | Hypertension (HTN), obesity, diabetes mellitus (DM) |

| P4 | A patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life | CV or pulmonary disease that limits activity, severe diabetes with systemic complications, history of myocardial infarction (MI), angina pectoris, or poorly controlled HTN |

| P5 | A moribund patient who is not expected to survive without the operation | Severe cardiac, pulmonary, renal, hepatic, or endocrine dysfunction |

| P6 | A patient declared brain dead whose organs are being removed for donor purpose | Patients may have a wide variety of dysfunctions that are being managed to optimize blood flow to the heart and organs (e.g., aggressive fluid replacement and blood pressure medications) |

Modified from Physical Status (PS) Classification. Reprinted with permission of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, 520 N. Northwest Highway, Park Ridge, Illinois, 60068-2573, http://www.asahq.org/clinical/physicalstatus.htm, 2010.

Nursing Knowledge Base

Nurses made significant contributions demonstrating the benefit of preoperative education and preparation on positive patient outcomes following surgery. Structured preoperative teaching includes the AORN (2011) standards to prevent pulmonary and circulatory complications. Educating a patient before surgery can lead to increased patient satisfaction and decreased anxiety (Rosen, 2008).

Significant evidence-based knowledge is also available for proper wound care interventions. Nursing research contributes to our knowledge of the characteristics of wound healing and the types of applications most likely to be beneficial after surgery. Chapter 48 describes in detail a variety of interventions used to treat wounds, including surgical wounds.

Within the operating room (OR) setting, nursing knowledge improves the standards for infection control and patient safety. Evidence-based practice changes within the OR improve the quality of care for surgical patients and ultimately patient outcomes.

Critical Thinking

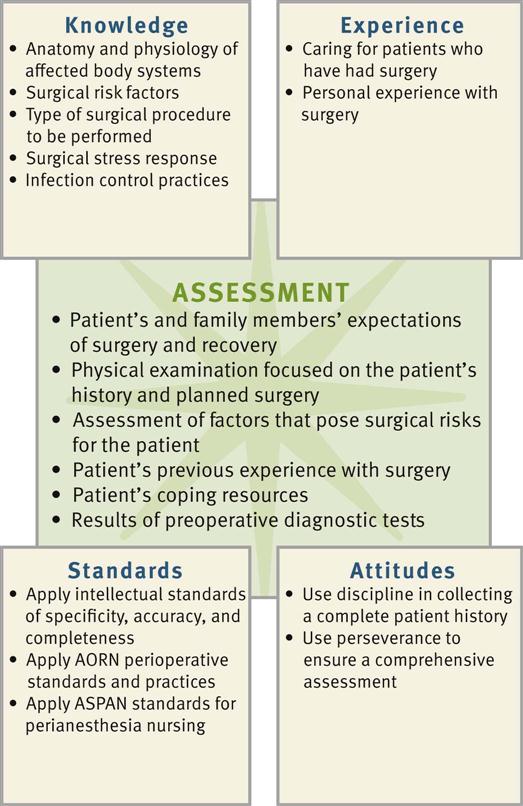

Successful critical thinking synthesizes knowledge, information gathered from patients, previous experience, critical thinking attitudes, and intellectual and professional standards. Clinical judgments require you to anticipate the necessary information, analyze the data, and make decisions about patient care. A patient’s condition is always changing. During assessment (Fig. 50-1) consider all of the elements that build toward making appropriate nursing diagnoses.

When caring for the perioperative patient, integrate knowledge from anatomy and physiology, pathophysiology, and the surgical stress response, along with previous experiences in caring for surgical patients. Apply this knowledge using a patient-centered care approach to making clinical decisions. The use of critical thinking attitudes ensures that a plan of care is comprehensive and incorporates evidence-based principles for successful perioperative care (e.g., airway management, infection control, pain management, and discharge planning). The use of professional standards developed by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ) (http://www.ahrq.gov), AORN (http://www.aorn.org), the American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses (ASPAN) (http://www.aspan.org), and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) (http://www.asahq.org) provides valuable guidelines for perioperative management and evaluation of process and outcomes. Always review these guidelines within the context of new emerging evidence-based practice, agency policies, and the scope of practice of the state in which you practice.

Preoperative Surgical Phase

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop and implement an individualized plan of care.

Patients having surgery enter the health care setting in different stages of health. A patient may enter the hospital or ambulatory surgical center on a predetermined day feeling relatively healthy and prepared to face elective surgery. In contrast, a person in a motor vehicle crash may face emergency surgery with no time to prepare. The ability to establish rapport and maintain a professional relationship with the patient is an essential component of the preoperative phase. You must do this quickly, with compassion and effectiveness.

The patient meets many health care personnel, including surgeons, nurse anesthetists, anesthesiologists, surgical technologists, and nurses. All play a role in the patient’s care and recovery. Family members attempt to provide support through their presence but face many of the same stressors as the patient. You need to effectively communicate with the patient and family because the nurse-patient relationship is the foundation of care (see Chapter 24). Assess the patient’s physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being and cultural heritage; recognize the degree of surgical risk; coordinate diagnostic tests; identify nursing diagnoses and nursing interventions; and establish outcomes in collaboration with the patient and the patient’s family. Communicate pertinent data and the plan of care to the surgical team members.

Assessment

A thorough patient assessment and critical analysis of findings ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care. The aim of the preoperative assessment is to identify the patient’s normal preoperative function to recognize, prevent, and minimize possible postoperative complications. Ambulatory and same-day surgical programs offer challenges in gathering a complete assessment in a short time. A multidisciplinary team approach is essential. Patients are admitted only hours before surgery; thus it is important for you to organize and verify data obtained before surgery and implement a perioperative plan of care. This occurs both in ASCs and with patients who require a hospital stay.

Most assessments begin before admission for surgery—in the health care provider’s office, preadmission clinic, or anesthesia clinic or by telephone. Some patients answer a self-report inventory. Other times a health care provider performs a physical examination or orders laboratory tests. Before surgery nurses begin teaching, answer questions, and begin paperwork. This streamlines the care required by the patient on the day of surgery.

So as not to waste time duplicating information from the preoperative examination, focus on key measurements for all body systems to ensure that no one overlooked any obvious problems. Also make sure that the patient understands any previous education. Even though the surgeon screens the patient before scheduling surgery, preoperative assessment occasionally reveals an abnormality that delays or cancels surgery. For example, consider an infection in a patient with a cough and low-grade fever on admission and notify the surgeon immediately.

Through the Patient’s Eyes

Individualize each plan of care to be patient centered, including the patient’s expectations of surgery and the road to recovery. Does the patient expect full pain relief or simply to have his or her pain reduced? Does the patient expect to be independent immediately after surgery, or does he or she expect to be fully dependent on the nurse or family? These are only a few of the questions that you need to ask to establish a plan of care that matches the patient’s needs and expectations. It is important to consider the patient’s values as they relate to the nature of surgery. Also be sure to incorporate any of his or her previous experiences with surgery (e.g., pain, ability to advance through postoperative exercises, experience with diet) so your current assessment is accurate and relevant. Findings often reveal patient preferences to postoperative care allowing for a more individualized care approach.

Nursing History

Conduct an initial interview to collect a patient history similar to that described in Chapter 30. If a patient is unable to relate all of the necessary information, rely on family members as resources.

Medical History

A review of the patient’s medical history includes past illnesses and surgeries and the primary reason for seeking medical care. The patient’s current medical record and medical records from past hospitalizations are excellent sources of data. Preexisting illnesses influence patients’ abilities to tolerate surgery and nurses’ choices of therapies to help them reach full recovery (Table 50-3). The history of previous surgery influences the level of physical care required after an upcoming surgical procedure. Screen patients scheduled for ambulatory surgery for medical conditions that increase the risk for complications during or after surgery. For example, a patient who has a history of heart failure may experience a further decline in cardiac function during and after surgery. The patient with heart failure in the preoperative period may require beta-blocker medications, intravenous (IV) fluids infused at a slower rate, or administration of a diuretic after blood transfusions. Box 50-1 highlights an example of a focused assessment for a patient with a cardiac history.

TABLE 50-3

Medical Conditions That Increase Risks of Surgery

| TYPE OF CONDITION | REASON FOR RISK |

| Bleeding disorders (thrombocytopenia, hemophilia) | Increase risk of hemorrhage during and after surgery. |

| Diabetes mellitus | Increases susceptibility to infection and impairs wound healing from altered glucose metabolism and associated circulatory impairment. Stress of surgery often results in hyperglycemia (Lewis et al., 2011). |

| Heart disease (recent myocardial infarction, dysrhythmias, heart failure) and peripheral vascular disease | Stress of surgery causes increased demands on myocardium to maintain cardiac output. General anesthetic agents depress cardiac function. |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | Administration of opioids increases risk of airway obstruction after surgery. Patients desaturate as revealed by drop in oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry. |

| Upper respiratory infection | Increases risk of respiratory complications during anesthesia (e.g., pneumonia and spasm of laryngeal muscles). |

| Liver disease | Alters metabolism and elimination of drugs administered during surgery and impairs wound healing and clotting time because of alterations in protein metabolism. |

| Fever | Predisposes patient to fluid and electrolyte imbalances and may indicate underlying infection. |

| Chronic respiratory disease (emphysema, bronchitis, asthma) | Reduces patient’s means to compensate for acid-base alterations (see Chapter 41). Anesthetic agents reduce respiratory function, increasing risk for severe hypoventilation. |

| Immunological disorders (leukemia, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS], bone marrow depression, and use of chemotherapeutic drugs or immunosuppressive agents) | Increases risk of infection and delayed wound healing after surgery. |

| Abuse of street drugs | People abusing drugs sometimes have underlying disease (human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], hepatitis) that affects healing. |

| Chronic pain | Regular use of pain medications often results in higher tolerance. Increased doses of analgesics are sometimes necessary to achieve postoperative pain control. |

Risk Factors

Various conditions and factors increase a person’s risk in surgery. Knowledge of risk factors enables you to take necessary precautions in planning care.

Age

Very young and older adults are at risk for complications because of immature or declining physiological status. Mortality rates are higher in very young and very old surgical patients. During surgery nurses and health care providers are especially concerned with maintaining an infant’s normal body temperature. The infant has an underdeveloped shivering reflex, and often wide temperature variations occur. Anesthesia adds to the risk because anesthetics often cause vasodilation and heat loss.

During surgery an infant has difficulty maintaining a normal circulatory blood volume. He or she has considerably less total blood volume than an older child or adult. Even a small amount of blood loss is serious. A reduced circulatory volume makes it difficult for the infant to respond to increased oxygen demands during surgery. In addition, the infant is highly susceptible to complications associated with dehydration. However, if blood or fluids are replaced too quickly, overhydration may occur. Other unique aspects of a child’s surgical care include airway management, management of temperature alterations, and treatment of emergence delirium or delayed emergence from anesthesia.

With advancing age patients have less physical capacity to adapt to the stress of surgery because of deterioration in certain body functions. Perioperative registered nurses (RNs) should recognize the physiological, cognitive/psychological, and sociological changes associated with aging and understand that age alone puts older adults at risk for surgical complications (AORN, 2010). Despite the risk, the majority of patients undergoing surgery are older adults. Table 50-4 summarizes physiological factors that place older patients at risk during surgery.

TABLE 50-4

Physiological Factors That Place the Older Adult at Risk During Surgery

| ALTERATIONS | RISKS | NURSING IMPLICATIONS |

| Cardiovascular System | ||

| Degenerative change in myocardium and valves | Decreased cardiac reserve puts older adults at risk for decreased cardiac output, especially during times of stress (AORN, 2010) | Assess baseline vital signs for tachycardia, fatigue, and arrhythmias (AORN, 2010). |

| Rigidity of arterial walls and reduction in sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation to the heart | Alterations predispose patient to postoperative hemorrhage and rise in systolic and diastolic blood pressure | Maintain adequate fluid balance to minimize stress to the heart. Ensure that blood pressure level is adequate to meet circulatory demands. |

| Increase in calcium and cholesterol deposits within small arteries; thickened arterial walls | Predispose patient to clot formation in lower extremities | Instruct patient in techniques of leg exercises and proper turning. Apply elastic stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) devices. Administer anticoagulants as ordered by health care provider. Provide education regarding effects, side effects, and dietary considerations. |

| Integumentary System | ||

| Decreased subcutaneous tissue and increased fragility of skin | Prone to pressure ulcers and skin tears | Assess skin every 4 hours; pad all bony prominences during surgery. Turn or reposition at least every 2 hours. |

| Pulmonary System | ||

| Decreased respiratory muscle strength and cough reflex (AORN, 2010) | Increased risk for atelectasis | Instruct patient in proper technique for coughing, deep breathing, and use of spirometer. Ensure adequate pain control to allow for participation in exercises. |

| Reduced range of movement in diaphragm | Residual capacity (volume of air is left in lung after normal breath) increased, reducing amount of new air brought into lungs with each inspiration | When possible, have patient ambulate and sit in chair frequently. |

| Stiffened lung tissue and enlarged air spaces | Blood oxygenation reduced | Obtain baseline oxygen saturation; measure throughout perioperative period. |

| Gastrointestinal System | ||

| Gastric emptying delayed | Increases the risk for reflux and indigestion (AORN, 2010) | Position patient with head of bed elevated at least 45 degrees. Reduce size of meals in accordance with ordered diet. |

| Renal System | ||

| Decreased renal function, with reduced blood flow to kidneys | Increased risk of shock when blood loss occurs; increased risk for fluid and electrolyte imbalance (AORN, 2010) | For patients hospitalized before surgery, determine baseline urinary output for 24 hours. |

| Reduced glomerular filtration rate and excretory times | Limits ability to eliminate drugs or toxic substances | Assess for adverse response to drugs. |

| Decreased bladder capacity | Increases the risk for urgency, incontinence, and urinary tract infections (AORN, 2010) (Sensation of need to void often does not occur until bladder is filled) | Instruct patient to notify nurse immediately when sensation of bladder fullness develops. Keep call light and bedpan within easy reach. Toilet every 2 hours or more frequently if indicated. |

| Neurological System | ||

| Sensory losses, including reduced tactile sense and increased pain tolerance | Decreased ability to respond to early warning signs of surgical complications | Inspect bony prominences for signs of pressure that patient is unable to sense. Orient patient to surrounding environment. Observe for nonverbal signs of pain. |

| Blunted febrile response during infection (AORN, 2010) | Increased risk of undiagnosed infection | Ensure careful, close monitoring of patient temperature; provide warm blankets; monitor heart function; warm intravenous fluids (AORN, 2010). |

| Decreased reaction time | Confusion and delirium after anesthesia; increased risk for falls | Allow adequate time to respond, process information, and perform tasks. Perform fall risk screening and institute fall precautions. Screen for delirium with validated tools. Orient frequently to reality and surroundings. |

| Metabolic System | ||

| Lower basal metabolic rate | Reduced total oxygen consumption | Ensure adequate nutritional intake when diet is resumed but avoid intake of excess calories. |

| Reduced number of red blood cells and hemoglobin levels | Reduced ability to carry adequate oxygen to tissues | Administer necessary blood products. Monitor blood test results and oxygen saturation. |

| Change in total amounts of body potassium and water volume | Greater risk for fluid or electrolyte imbalance | Monitor electrolyte levels and supplement as necessary. Provide cardiac monitoring (telemetry) as needed. |

Nutrition

Before surgery assess if the patient is on a therapeutic diet and if there are any factors influencing food intake such as ability to chew and swallow and the presence of regurgitation after meals. This affects your choice of postoperative foods and liquids. In addition, normal tissue repair and resistance to infection depend on adequate nutrients. Surgery intensifies this need. After surgery a patient requires at least 1500 kcal/day to maintain energy reserves. Increased protein, vitamins A and C, and zinc facilitate wound healing (see Chapters 44 and 48). A patient who is malnourished is prone to poor tolerance to anesthesia, negative nitrogen balance from lack of protein, delayed blood-clotting mechanisms, infection, and poor wound healing. Assess the patient’s weight and height to determine body mass index. Many hospitalized patients display some degree of malnutrition. If a patient has elective surgery, attempt to correct nutritional imbalances before surgery. However, if a patient who is malnourished must undergo an emergency procedure, efforts to restore nutrients occur after surgery.

Obesity

Obesity increases surgical risk by reducing ventilatory and cardiac function. Obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, and heart failure are common in the bariatric (obese) population. Embolus, atelectasis, and pneumonia are common postoperative complications in the patient who is obese. He or she often has difficulty resuming normal physical activity after surgery and is susceptible to poor wound healing and wound infection because of the structure of fatty tissue, which contains a poor blood supply. This slows delivery of essential nutrients, antibodies, and enzymes needed for wound healing (see Chapter 48). It is often difficult to close the surgical wound of a patient who is obese because of the thick adipose layer; thus he or she is at risk for dehiscence (opening of the suture line) and evisceration (abdominal contents protruding through surgical incision).

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a syndrome of periodic, partial, or complete obstruction of the upper airway during sleep. Patients with diagnosed OSA have an increased incidence of postoperative complications, the most frequent being oxygen desaturation (Liao et al., 2009). Assess for a history of diagnosed OSA and use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV), or apnea monitoring. Instruct patients who use CPAP or NIPPV to bring their machine to the hospital or surgery center. Many patients with OSA are undiagnosed; thus it is becoming standard practice to assess for risk of OSA before surgery. It is necessary to ask the patient and sleep partner about symptoms of OSA such as snoring, apnea during sleep, frequent arousals during sleep, morning headaches, daytime somnolence, and chronic fatigue (ASA, 2006; Seet and Chung, 2010).

Immunocompromise

Patients with conditions that alter immune function are more at risk for developing infection after surgery. Examples include patients with cancer, bone marrow alterations, and those who undergo radiation therapy. Radiation is sometimes given before surgery to reduce the size of a cancerous tumor so it can be removed surgically. It has some unavoidable effects on normal tissue such as excess thinning of skin layers, destruction of collagen, and impaired vascularization of tissue. Ideally the surgeon waits to perform surgery 4 to 6 weeks after completion of radiation treatments. Otherwise the patient may face serious wound-healing problems. In addition, the use of chemotherapeutic drugs for cancer treatment, immunosuppressive medications for preventing rejection after organ transplantation, and steroids for treating a variety of inflammatory or autoimmune conditions increases the risk for infection.

Fluid and Electrolyte Imbalance

The body responds to surgery as a form of trauma. Severe protein breakdown causes a negative nitrogen balance (see Chapter 44) and hyperglycemia. Both of these effects decrease tissue healing and increase the risk of infection. As a result of the adrenocortical stress response, the body retains sodium and water and loses potassium within the first 2 to 5 days after surgery. The severity of the stress response influences the degree of fluid and electrolyte imbalance. Extensive surgery results in a greater stress response. A patient who is hypovolemic or who has serious preoperative electrolyte alterations is at significant risk during and after surgery. For example, an excess or depletion of potassium increases the chance of dysrhythmias during or after surgery. If the patient has preexisting diabetes mellitus or renal, gastrointestinal (GI), or cardiovascular abnormalities, the risk of fluid and electrolyte alterations is even greater.

Pregnancy

The perioperative plan of care addresses not one, but two patients: the mother and the developing fetus. The pregnant patient has surgery only on an emergent or urgent basis. Because all of the mother’s major systems are affected during pregnancy, the risk for intraoperative complications is increased. General anesthesia is administered with caution because of the increased risk of fetal death and preterm labor. Psychological assessment of mother and family is essential.

Perceptions and Knowledge Regarding Surgery

A patient’s past experience with surgery influences physical and psychological responses to a procedure. Assess the patient’s previous experiences with surgery as a foundation for anticipating his or her needs, providing teaching, addressing fears, and clarifying concerns. Ask the patient to discuss the previous type of surgery, level of discomfort, extent of disability, and overall level of care required. Address any complications that the patient experienced. It is also important to assess patients for motion sickness and nausea and vomiting during previous surgeries since these factors increase the risk for aspiration (McCaffrey, 2007). Prior anesthesia records are a useful source of information if previous problems occurred.

The surgical experience affects the family unit as a whole. Therefore prepare both the patient and the family for the surgical experience. Understanding of a patient’s and family’s knowledge, expectations, and perceptions allows you to plan teaching and provide individualized emotional support measures.

Each patient fears surgery. Some fears are the result of past hospital experiences, warnings from friends and family, or lack of knowledge. Assess the patient’s understanding of the planned surgery, its implications, and planned postoperative activities. Ask questions such as “Tell me what you think will happen before and after surgery” or “Explain what you know about surgery.” Nurses face ethical dilemmas when patients are misinformed or unaware of the reason for surgery. Confer with the surgeon if the patient has an inaccurate perception or knowledge of the surgical procedure before the patient is sent to the surgical suite. Also determine whether the health care provider explained routine preoperative and postoperative procedures and assess the patient’s readiness and willingness to learn. When a patient is well prepared and knows what to expect, reinforce his or her knowledge.

Medication History

Presence of preexisting co-morbid conditions such as hypertension, renal or heart disease, respiratory disorders, and diabetes increases a patient’s surgical risk. If a patient regularly uses prescription or over-the-counter medications, the surgeon or anesthesia provider may temporarily discontinue the drugs before surgery or adjust the dosages. Certain medications pose greater risks for surgical complications (Table 50-5). Instruct patients to ask the health care provider if they need to take usual medications the morning of surgery. Also ask them if they take any herbal preparations because many patients do not view herbs as medications and often omit them from their medication history (see Chapter 32). Certain herbs interfere with the action of other medications (consult the pharmacist). For hospitalized patients prescription drugs taken before surgery are automatically discontinued after surgery unless the health care provider reorders them. The use of a medication reconciliation process (see Chapter 31) is common practice to ensure that at the time of a patient’s admission a complete list of the medications the patient is taking at home is created and documented. The patient and, as needed, the family needs to be involved to be sure that there is an accurate and current medication list for the patient (TJC, 2011).

TABLE 50-5

Drugs with Special Implications for the Surgical Patient

| DRUG CLASS | EFFECTS DURING SURGERY |

| Antibiotics | Potentiate (enhance action of) anesthetic agents. If taken within 2 weeks before surgery, aminoglycosides (gentamicin, neomycin, tobramycin) may cause mild respiratory depression from depressed neuromuscular transmission. |

| Antidysrhythmics | Medications (e.g., beta blockers) can reduce cardiac contractility and impair cardiac conduction during anesthesia. |

| Anticoagulants | Medications such as warfarin (Coumadin) or aspirin alter normal clotting factors and thus increase risk of hemorrhaging. Discontinue at least 48 hours before surgery. |

| Anticonvulsants | Long-term use of certain anticonvulsants (e.g., phenytoin [Dilantin] and phenobarbital) alters metabolism of anesthetic agents. |

| Antihypertensives | Medications such as beta blockers and calcium channel blockers interact with anesthetic agents to cause bradycardia, hypotension, and impaired circulation. They inhibit synthesis and storage of norepinephrine in sympathetic nerve endings. |

| Corticosteroids | With prolonged use corticosteroids such as prednisone cause adrenal atrophy, which reduces the ability of the body to withstand stress. Before and during surgery, dosages are often temporarily increased. |

| Insulin | Patients’ need for insulin changes after surgery. Stress response and intravenous (IV) administration of glucose solutions often increase dosage requirements after surgery. Decreased nutritional intake often decreases dosage requirements. |

| Diuretics | Diuretics such as furosemide (Lasix) potentiate electrolyte imbalances (particularly potassium) after surgery. |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen) inhibit platelet aggregation and prolong bleeding time, increasing susceptibility to postoperative bleeding. |

| Herbal therapies: ginger, gingko, ginseng | These herbal therapies have the ability to affect platelet activity and increase susceptibility to postoperative bleeding. Ginseng is reported to increase hypoglycemia with insulin therapy. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree