Women’s Health Care

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Explain examinations and screening procedures that are recommended to maintain the health of women.

• Discuss osteoporosis and measures to reduce severity.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch

Women are not pregnant the majority of their lives, and some are never pregnant. However, they often consider their primary care provider for their unique preventive health care to be the same person they saw for obstetrics or annual Papanicolaou (Pap) tests. Many obstetricians continue to provide gynecology care after retiring from obstetrics. Certified nurse-midwives usually provide preventive health care to nonpregnant women. The advanced practice women’s health nurse practitioner (WHNP) provides basic reproductive system care to women in many settings. Therefore the provider that a woman sees for her well-woman examination (WWE) must be prepared to examine her for nonreproductive problems to determine referrals that she may need. A nurse in the outpatient setting plays varied roles in routine assessments, screening procedures, and management of the woman’s specific health concerns acting as educator and advocate for the woman. Nurses explain screening and diagnostic procedures, clarify options so that women can make informed decisions about care, and provide support to women when they experience disruptions in their health.

Women’s Health Initiative

The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) began in 1991 by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NHLBI) as a 15-year national study focusing on best prevention of four diseases that have a major effect on postmenopausal women of all races and socioeconomic backgrounds. The study was extended to 2010 adding research findings for these diseases:

Breast cancer, cardiovascular disease, and osteoporosis are covered in this chapter. For additional nursing information about these three diseases and about cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer, see a medical-surgical nursing text.

Information about clinical trials, observational studies, and community prevention measures that are now finished can be found at www.nhlbi.nih.gov/whi/.

Healthy People 2020

Healthy People 2020 has now been released with a total of 13 new topics with objectives. Several goals in Healthy People 2020 that are relevant to women’s health include:

Information on many other topics and updates as they occur can be found at www.healthypeople.gov.

Health Maintenance

Health maintenance refers to measures that can be taken for prevention or early detection of specific diseases. Unfortunately, many women do not take advantage of recommended health maintenance procedures. Some seek care only when they have a problem. For others, the only health care they receive comes from a gynecologist or nurse practitioner, often with their annual checkup. Therefore it is important that those who provide health care for women are familiar with principles of screening and counseling in areas that are not traditionally associated with gynecology, such as assessing risk factors for colon cancer and heart disease.

Health History

The health history is most important in determining risk factors for a variety of conditions. The woman’s health history may also help her identify what she does that may strengthen her health. The focus of a health history depends on the woman’s age, but some topics need to be discussed with all women. Box 32-1 provides a summary of information that should be obtained.

Family history is essential to assess risk profiles to identify risks that cannot be modified. Family and/or personal history of hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, osteoporosis, and thyroid disease suggests screening tests, and examinations are needed. A list of family members who have had cancer, its type, and their ages when it was discovered provides important information about the risk of cancer, particularly breast and colon cancer.

Discussions of drug use, prescribed, over-the-counter (OTC), and illicit, should be done, including use of any complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) that many people do not think are medical therapy.

Physical Assessment

A thorough physical examination is necessary to detect general health problems. Vital signs and weight are measured at each visit. Height is taken at the initial examination and yearly after that. Loss of height and abnormal curvature of the vertebral column (dorsal kyphosis or scoliosis) are important observations in evaluating osteoporosis.

The heart is auscultated at the initial visit to determine whether the rate and rhythm are normal and to detect heart murmurs. The extremities are observed for varicosities or edema, and pedal pulses are palpated. Palpation of the abdomen for tenderness, masses, or distention is an important part of the physical examination.

Additional assessments are necessary if the woman is at higher risk for disease. For example, if the woman has a family history of diabetes mellitus, an oral glucose tolerance test or glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) may be indicated. If she has a history of multiple sexual partners or a sexual partner with multiple contacts, she may require testing for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing.

Preventive Counseling

Physical examination provides an excellent opportunity to counsel women about preventive care. Major preventable problems are obesity, inactivity, and smoking. About one third of adults in the United States were overweight and about two thirds were overweight or obese in 2007-2008. Obesity often begins in childhood and almost one in five children 5 years or older was obese in the 2007-2008 statistics. A normal adult body mass index (BMI) is from 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2. BMI of 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2 is overweight, 30.0 to 34.9 kg/m2 is obese, while grade 2 obesity is a BMI of 35.0 kg/m2 or higher, and grade 3 is a BMI of 40.0 kg/m2 or higher. A BMI higher than 30.0 kg/m2 correlates with higher mortality in women. Obesity in women has continued to increase from 25% of women in 1988 to 35% in 2008. Percentage of obese women in the 2008 population varied by race and ethnicity (National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS], 2010):

Obesity is associated with diabetes, hypertension, and other chronic diseases, including breast, endometrial, and colon cancers. Inactivity associated with obesity brings other problems such as osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, dyslipidemia (abnormal amount of cholesterol and other fats in the blood), stroke, and coronary artery disease (CAD). Gynecologic conditions may include abnormal menses or infertility (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011b).

Infections, often STDs, are a source of many health problems that should be reinforced in the nursing care of women. Chlamydia and gonorrhea are the two most frequently reported STDs. Use of latex condoms provides some protection against transmission of viruses, such as HIV and human papillomavirus (HPV), which is a risk factor for cervical cancer (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2010a; CDC, 2010a, 2010c).

The history or physical examination may indicate other areas for which counseling or screening should be provided. These include the dangers of malignant melanoma with repeated exposure to ultraviolet rays of the sun. In addition, the health risks associated with alcohol and other substance abuse may be particularly important for some women. Domestic violence may be discovered, requiring counseling for the woman to deal with this complex social problem.

Screening Procedures

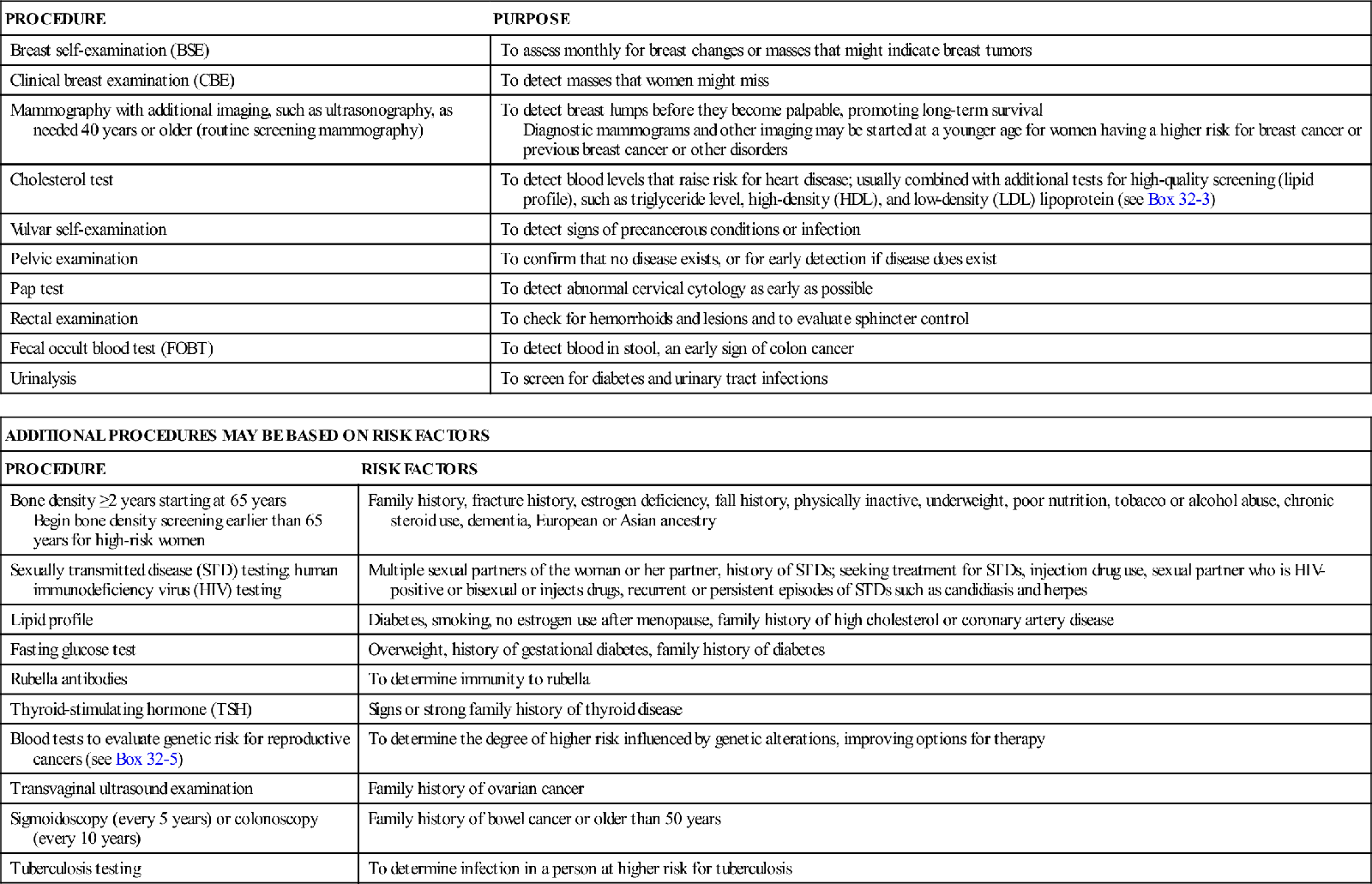

Screening procedures are important because early diagnosis allows early therapy while the pathologic process is still treatable. A variety of screening procedures are recommended for all women, including three screening procedures for early detection of breast cancer as well as vulvar self-examination and screening for cervical cancer. Other procedures are based on the woman’s age and risk status. Table 32-1 summarizes purposes for common screening procedures for women.

TABLE 32-1

| PROCEDURE | PURPOSE |

| Breast self-examination (BSE) | To assess monthly for breast changes or masses that might indicate breast tumors |

| Clinical breast examination (CBE) | To detect masses that women might miss |

| Mammography with additional imaging, such as ultrasonography, as needed 40 years or older (routine screening mammography) | To detect breast lumps before they become palpable, promoting long-term survival Diagnostic mammograms and other imaging may be started at a younger age for women having a higher risk for breast cancer or previous breast cancer or other disorders |

| Cholesterol test | To detect blood levels that raise risk for heart disease; usually combined with additional tests for high-quality screening (lipid profile), such as triglyceride level, high-density (HDL), and low-density (LDL) lipoprotein (see Box 32-3) |

| Vulvar self-examination | To detect signs of precancerous conditions or infection |

| Pelvic examination | To confirm that no disease exists, or for early detection if disease does exist |

| Pap test | To detect abnormal cervical cytology as early as possible |

| Rectal examination | To check for hemorrhoids and lesions and to evaluate sphincter control |

| Fecal occult blood test (FOBT) | To detect blood in stool, an early sign of colon cancer |

| Urinalysis | To screen for diabetes and urinary tract infections |

| ADDITIONAL PROCEDURES MAY BE BASED ON RISK FACTORS | |

| PROCEDURE | RISK FACTORS |

| Bone density ≥2 years starting at 65 years Begin bone density screening earlier than 65 years for high-risk women | Family history, fracture history, estrogen deficiency, fall history, physically inactive, underweight, poor nutrition, tobacco or alcohol abuse, chronic steroid use, dementia, European or Asian ancestry |

| Sexually transmitted disease (STD) testing; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing | Multiple sexual partners of the woman or her partner, history of STDs; seeking treatment for STDs, injection drug use, sexual partner who is HIV-positive or bisexual or injects drugs, recurrent or persistent episodes of STDs such as candidiasis and herpes |

| Lipid profile | Diabetes, smoking, no estrogen use after menopause, family history of high cholesterol or coronary artery disease |

| Fasting glucose test | Overweight, history of gestational diabetes, family history of diabetes |

| Rubella antibodies | To determine immunity to rubella |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) | Signs or strong family history of thyroid disease |

| Blood tests to evaluate genetic risk for reproductive cancers (see Box 32-5) | To determine the degree of higher risk influenced by genetic alterations, improving options for therapy |

| Transvaginal ultrasound examination | Family history of ovarian cancer |

| Sigmoidoscopy (every 5 years) or colonoscopy (every 10 years) | Family history of bowel cancer or older than 50 years |

| Tuberculosis testing | To determine infection in a person at higher risk for tuberculosis |

∗American Cancer Society. (2011). Breast cancer: Early detection. Retrieved from www.cancer.org.

Breast Self-Examination

Most breast cancers are discovered by the woman herself. Yet only about half of all women examine their breasts each month. Breast self-examination (BSE) (Box 32-2) is ideally done monthly by a woman starting at 20 years. A good time is about 1 week after the onset of menses, when hormonal influences on the breasts are at a low level. If the woman no longer menstruates, choosing a day that is easy to remember and perform her BSE that month is ideal. An example is the first day of the month.

Clinical Breast Examination

Clinical breast examination (CBE) performed by a health care professional may detect questionable areas that the woman misses during BSE. It should be routinely performed every 3 years for women ages 20 to 39 years and yearly for those 40 years or older. Some conditions need more frequent examinations because they are associated with a higher risk for breast cancer

than the general population. The examination includes inspection and palpation.

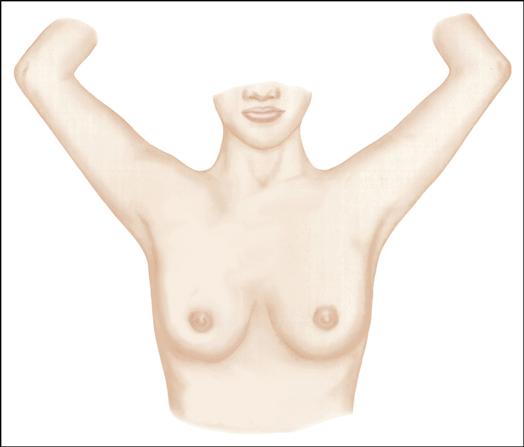

Inspection

Follow these steps for breast inspection:

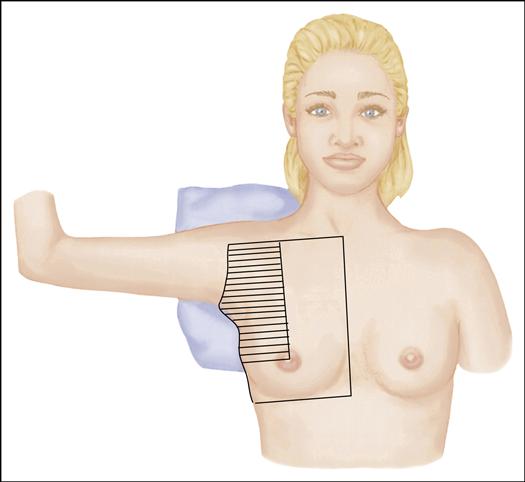

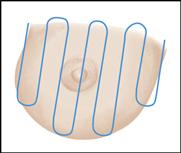

Palpation

Follow these steps for breast palpation:

Mammography

Mammography may be used either to screen for cancer or assist in the diagnosis of a palpable mass in the breast. Mammography is the primary screening tool that can detect breast lumps long before they are large enough to be palpated. This procedure, often accompanied by ultrasound studies, allows early diagnosis and treatment and thus increases the chance of long-term survival.

ACS (2011a) recommends yearly mammography to screen for breast cancer in women starting at age 40 years. Women at higher risk for breast cancer or with a suspicious growth in the breast may need mammography and other diagnostic studies at a younger age. Despite the value of screening mammography, many women have never had a mammogram (study of breast tissue using very-low-dose-radiography). Reasons for this include expense, fear that x-ray exposure will cause cancer, fear of pain, and reluctance to hear “bad news.”

Nurses provide information and reassurance to help the woman overcome her objections to the use of this valuable screening tool. Although mammography is relatively expensive, the cost is often covered by health insurance or Medicaid and Medicare, and screening mammograms are frequently offered by the community at low cost. It is important to acknowledge that some discomfort occurs when the breast is compressed between two plates while the radiograph is taken. One measure that reduces discomfort is scheduling the mammography after a menstrual period, when the breasts are less tender. Knowledge that the risk of mammography is minimal to nonexistent because of the very-low-dose x-rays used may help women overcome some of their fear. Digital mammography, although more expensive, may provide clearer imaging. Ultrasound images or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be used if needed.

No screening test is 100% accurate. Therefore nurses must emphasize that the mammogram should be performed in conjunction with a monthly BSE and recommended frequency of CBEs.

Vulvar Self-Examination

Vulvar self-examination should be performed monthly by all women older than 18 years and by those younger than 18 years who are sexually active. Chronic HPV is a risk factor for vulvar cancer and can spread to other parts of the body. Vulvar self-examination is visual inspection and palpation of the female external genitalia to detect signs of precancerous conditions or infections (ACS, 2011f).

The woman should sit in a well-lighted area and use a hand-held mirror to see her external genitalia. She is taught to examine the vulva in a systematic manner, starting at the mons pubis and progressing to the clitoris, labia minora, labia majora, perineum, and anus. Palpation of the vulvar area should accompany visual inspection. The woman should report new moles, warts or growths of any kind, ulcers, sores, changes in skin color, or areas of inflammation or itching should be reported to her health care provider as soon as possible.

Pelvic Examination

The gynecologic assessment includes a pelvic examination. The woman is advised to schedule the examination about 2 weeks after her menstrual period and not to douche or have sexual intercourse for at least 48 hours before the examination. She is advised to avoid vaginal medications, douches, sprays, or deodorants that may interfere with a Pap test or other specimens obtained during the examination.

Before the examination, the procedure is carefully explained and the woman empties her bladder. She is placed in a lithotomy position, with a pillow under her head. If she wishes, she may assume a semi-sitting position and use a hand mirror so that she can observe the external genitalia and the examination. She is draped so that only the parts being examined are exposed.

Equipment needed for the pelvic examination includes gloves, a speculum of appropriate size, plus equipment to obtain test specimens needed, including a Pap test, also called a Pap smear. Additional equipment for collecting tissue specimens for the Pap test may include slides, cotton swabs, a fixative agent, and a cytobrush and spatula. Newer equipment for the Pap test transfers cervical cells to a liquid preservative. A stool specimen may be obtained by the examiner during the rectal examination, and a slide for this specimen should also be available. Equipment to obtain specimens for suspected infection should also be available.

External Organs

The pelvic examination is conducted systematically and gently. The external organs are scrutinized for the degree of development or atrophy of the labia, the distribution of hair, and the character of the hymen. Any cysts, tumors, or inflammation of Bartholin’s glands are noted. The urinary meatus and Skene’s glands are inspected for purulent discharge. Perineal scarring caused by childbirth is noted.

Speculum Examination

A bivalve speculum of the appropriate size is used to inspect the vagina and cervix. If a metal speculum is used, it is usually warmed with tap water or a low-temperature electric warmer (heating pad) to reduce chilling and is gently inserted into the vagina. To avoid interference with test accuracy, vaginal lubrication with a water-based lubricant may be delayed until specimens, such as those for the Pap test or a culture and sensitivity for infection, are obtained. The size, shape, and color of the cervix are noted. A sample is taken for the Pap test. In addition, a sample of any unusual discharge is obtained for microscopic examination or culture.

Bimanual Examination

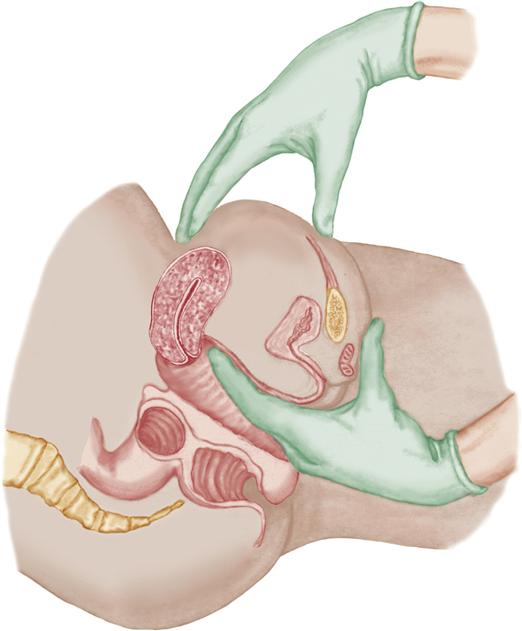

The bimanual examination provides information about the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. The labia are separated, and the gloved, lubricated index finger and middle finger of the examiner’s hand are inserted into the vaginal introitus.

The cervix is palpated for consistency, size, and tenderness to motion. The uterus is evaluated by placing the other hand on the abdomen with the fingers pressing gently just above the symphysis pubis so that the uterus can be felt between the examining fingers of both hands. The size, configuration, consistency, and motility of the uterus are evaluated (Figure 32-1).

The ovaries are palpated between the fingers of both hands. Because ovaries atrophy after menopause (permanent cessation of menstruation), it is often impossible to palpate the ovaries of a postmenopausal woman.

Pap Test

Purpose

Changes occur in cells of the cervix before cervical cancer develops. Cervical cytology, or the Pap test, is the most useful procedure for detecting precancerous and cancerous cells that may be shed by the cervix. Because infection with HPV may contribute to cervical neoplasms, testing for this virus is usually done during the pelvic examination.

Procedure

With the speculum blades open and the cervix in view, samples of the superficial layers of the cervix and endocervix are obtained. Samples are best obtained with a spatula and a cytobrush or with a broom-type sampling device. A sample is taken where most lesions develop, at the squamocolumnar junction (the border where developing squamous tissue meets the immature columnar epithelium).

Cervical tissue is placed on slides that are then sprayed with or immersed in a fixative solution before being sent to the laboratory for analysis if the older Pap test technique is used. Specimens obtained with the broom-type device, such as those in the liquid-based Thin-Prep or AutoCyte tests for cervical cancer, are rotated in the liquid that preserves the cells for analysis. The liquid-based tests use image processing to select the slides that need additional reading by a technician for best analysis.

Classification of Cervical Cytology

The widely used Bethesda system describes standard terminology for results of both the conventional Pap test and the liquid preparation. The most recent (2001) Bethesda system consists of three elements: (1) a statement of specimen adequacy, (2) a general category for analysis (normal or abnormal), and (3) a descriptive diagnosis for abnormal cytology, whether results suggest malignancy or another disorder.

Categories for epithelial cell abnormalities include:

1. Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS).

3. Squamous cell cancer that is likely to be invasive.

1. Atypical glandular cells of uncertain significance (AGCUS).

The woman’s follow-up depends on the nature of the abnormality and whether it is persistent. Pap tests that have persistent abnormal findings after a 3- to 6-month interval usually are evaluated by a colposcopy (examination of vaginal and cervical tissue with a colposcope for cell magnification), and biopsy is done for suspicious lesions.

DNA testing for the types of HPV that are most likely to cause cervical cancer is now available. The sample of cervical cells is collected in the same way as the Pap test. HPV cell types most strongly associated with cancers are HPV 16, HPV 18, HPV 31, HPV 33, and HPV 45. About two thirds of cervical cancers are caused by HPV 16 and 18 (ACS, 2011c).

Rectal Examination

The anus is inspected for hemorrhoids, inflammation, and lesions. The lubricated index finger is gently inserted, and sphincter tone is noted. A slide may be prepared to test for the presence of occult blood in stool.

Fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) is a useful screening measure for colorectal cancer. Special instructions are necessary to prevent false test results when materials for FOBT are sent home with the woman. She should be instructed to:

Breast Disorders

Benign Disorders of the Breast

There are four relatively common benign disorders of the breast. The risk for each disorder is related to a specific age.

Fibrocystic Breast Changes

Fibrocystic breast changes are common breast changes during the reproductive years. Fibrosis, or thickening of the normal breast tissue, occurs in the early stages. Cysts may form in the later stages and are felt as multiple, smooth, well-delineated nodules that have a tender, movable character. The lumpy, rubbery, or ropelike nodules often vary in size, from less than 1 cm to several centimeters. Fibrocystic changes are not cancerous, although atypical hyperplasia of the terminal breast ducts or lobules is associated with a greater risk for breast cancer. For women at higher risk for breast cancer, tissue specimens may be obtained to identify malignant changes (ACS, 2011e; Gemignani, 2008).

Pain and tenderness (mastalgia) as the breasts respond to hormonal variations during the menstrual cycle are common. The pain is often bilateral and most apparent during the premenstrual phase of the normal cycle. Women with large pendulous breasts may have pain associated with stretching of breast ligaments.

Treatment for fibrocystic breast changes is based on the woman’s symptoms. NSAIDs may provide adequate pain relief. Some women find that reducing their intake of caffeine and stimulants known as methylxanthines (coffee, tea, chocolate, and many soft drinks helps. Other women may need oral contraceptives for the painful fibrocystic changes (ACS, 2011c; Gemignani, 2008).

Fibroadenoma

Fibroadenomas are the most common benign tumors of the breast usually occurring during the teenage years and the 20s. Fibroadenomas are composed of both fibrous and glandular tissue. They are firm, rubbery, freely mobile nodules that may or may not be tender when palpated. Nodules are usually located in the upper, outer quadrant of the breast, and more than one may be present.

Treatment may involve careful observation for a few months. Persistent symptoms may require mammogram and ultrasound. Because the woman’s risk for breast cancer is increased with fibroadenomas, fine needle aspiration (FNA) or a core biopsy may be done to obtain cells for analysis, particularly if the mass continues to enlarge. The aspiration for cells may also collapse a cystic mass. A woman may prefer to have the mass surgically excised (ACS, 2011a; Gemignani, 2008).

Ductal Ectasia

Ductal ectasia usually occurs as a woman approaches menopause. It is characterized by dilation of the collecting ducts, which become distended and filled with cellular debris. This initiates an inflammatory process resulting in:

These signs and symptoms are similar to those of breast cancer, and accurate diagnosis through biopsy is vital. Although ductal ectasia is benign, the ducts may be excised to prevent further discharge or to remove an abscess that results from infection.

Intraductal Papilloma

Intraductal papilloma develops most often just before or during menopause. It occurs when papillomas (small elevations or protuberances) develop in the epithelium of the ducts of the breasts, often under the areola. As the papilloma grows, it causes trauma and erosion within the ducts that result in serous or serosanguineous discharge from the nipple. Treatment consists of excision of the mass and ductal area, plus analysis of nipple discharge to rule out a malignant tumor. Regular follow-up after the excision is essential to identify any subsequent malignancy early (ACS, 2011a, 2011e; Gemignani, 2008).

Diagnostic Evaluation

When a lesion or lump is discovered in the breast, the physician must determine if it is benign or malignant. Mammography is used to locate and visualize suspicious areas of the breasts. However, mammography is not as effective a screening technique if breasts are dense such as in a younger woman or because of changes associated with any disorder that is present. Digital mammograms are becoming more available and can be adjusted in size and clarity for the reader to better evaluate images. Ultrasound imaging differentiates fluid-filled cysts from solid tissue that is more likely to be malignant. For this reason, mammography and ultrasound examinations are often done together for improved diagnostic imaging. MRI may be used. Variations of these imaging techniques are used to guide biopsy and excision of some small masses.

Options for biopsy vary with the type of lesion. FNA can be performed to remove fluid or small tissue fragments for analysis of the cells. Core needle biopsy uses a larger needle to obtain a cylinder of tissue from an area of abnormal breast tissue. Open, or surgical, biopsy is performed to obtain tissue for analysis and to remove all or part of the lump of breast tissue. Other types of biopsy may be needed to obtain the most accurate tissue sample with minimal trauma. Examples of conditions that may require a biopsy include:

• Suspicious mass that persists through a menstrual cycle

• Bloody fluid aspirated from a cyst

• Failure of the mass to disappear completely after fluid aspiration

• Recurrence of the cyst after one or two aspirations

• Solid dominant mass not diagnosed as fibroadenoma

• Serous or serosanguineous nipple discharge

• Nipple ulceration or persistent crusting

• Skin edema and erythema suspicious for inflammatory breast carcinoma

• Suspicious findings on mammography or other imaging studies

• Known or possible genetic abnormality that increases a woman’s risk for breast cancer

Nursing Considerations

All women feel anxiety when a breast disorder is discovered. The apprehension continues for most women while they await a final diagnosis after biopsy. Some women may find it helpful to learn that most breast disorders are benign. However, as discussed, some benign disorders do increase the risk for later occurrence of cancer. For others, the most helpful intervention is to encourage them to express their concerns such as a genetic risk factor that increases their likelihood of developing cancer.

The nurse should reinforce medical explanations of procedures that are planned to diagnose the woman’s breast disorder, such as ultrasound examination, mammography, needle biopsy, or surgical biopsy. Explanations should include what the procedures entail and how long the woman will have to wait for results to be known.

Malignant Tumors of the Breast

Incidence

The risk for a woman to develop invasive breast cancer at some time in her life is slightly under one in eight. Fewer than 1% of men will develop breast cancer. The incidence of invasive breast cancer among women in the United States was more than 200,000 in 2007. Incidence of invasive breast cancer before age 45 years is 1 in 8 but 2 of 3 women age 55 years or older are likely to have invasive breast cancer when screened. White women have a higher incidence than African-American women, but African-American women have a higher risk of dying from breast cancer because they are more likely to have fast-growing tumors and be diagnosed at a more advanced stage. Asian-American, Hispanic, and Native Indian or Alaska Native women have a lower risk for developing cancer than whites or African-Americans (ACS, 2011a; Gemignani, 2008).

Predisposing Factors

Although the actual cause of breast cancer remains unknown, several factors are known to increase the risk for the development of breast and ovarian cancer or other diseases (see p. 774 [see Box 32-2] and p. 796 [see Box 32-5]). Mutations in two genes (BRCA1 and BRCA2) thought to be responsible for most cases of familial breast cancer have been identified. Mutation of the CHEK-2 gene has shown higher risk for development of breast cancer in both women and men. Study of genetic links to many types of cancers is ongoing. Because research has linked these and other genes to an increased risk for breast or other cancers, testing is offered to the woman having a higher risk or who has developed cancer at a younger age than expected.

Knowing risk factors is important to guide breast cancer screening and treatment processes so that a cancer is diagnosed at the earliest stage possible. It is also important for nurses to convey to women that many breast cancers develop in women with no known risk factors, whereas other women with one or more risk factors do not develop breast cancer.

Pathophysiology

About 65% to 80% of cases of breast cancer are infiltrating (invasive) ductal carcinoma, which originates in the epithelial lining of the mammary ducts. A cancer tumor becomes invasive when it is no longer confined to the duct and spreads to surrounding breast tissue. Another 10% of breast cancer cases are infiltrating lobular cancer, originating in the milk secreting pockets of breast tissue. Uncommon inflammatory cancers account for only 1% to 3% of breast cancers, but these cancers grow rapidly and are highly malignant. Growth of the tumor for common types of breast cancer occurs in irregular patterns and invades the lymphatic channels, eventually causing lymphatic edema and the dimpling of the skin that resembles an orange peel (peau d’orange) (ACS, 2011a; Gemignani, 2008).

Cancer cells are carried by the lymph channels to the lymph nodes, and 40% to 50% of patients have involvement of axillary lymph nodes at the time of diagnosis. By the time a patient consults a physician, breast cancer may be a systemic disease rather than confined to local tissue. Metastasis occurs when malignant cells are spread by blood and lymph systems to distant organs. The most common sites of metastasis are the brain, lungs, liver, and bones.

Manifestations

When breast cancer becomes palpable, the woman or caregiver feels a breast lump, thickening, or distortion. Dimpling, nipple retraction, or changes in the skin or shape of the breast may occur. Most breast pain is benign. Changes on the mammogram or ultrasound images may occur before the cancer is palpable.

Staging

Although confirmation of malignancy is the first step in evaluating the woman with cancer, staging is necessary to understand the severity of the cancer. Staging is generally based on the tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) system used to describe the cancer’s anatomic extent. Stages of breast cancer progress from stage 1, indicating a small tumor without lymphatic involvement or metastases, to stage 4, which indicates spread to lymph nodes and metastases to other organs. The stages are often used to determine treatment, and they are useful guides to prognosis. The type of cancer cell, the presence of hormone receptors, and the proliferative rate of the breast cancer cells are also important factors in the rate of recurrence.

Therapeutic Management

The woman with breast cancer must choose from a variety of treatments with involvement of multiple disciplines. A combination of surgical excision and adjuvant therapy (additional treatment that increases or enhances the action of the primary treatment) is often recommended. Radiation therapy of the breast minimizes chances of recurrence or spread of the cancer.

Surgical Treatment

The surgical procedure depends on the type, stage, and location of the disease. The most common surgeries are as follows (ACS, 2011a; Gemignani, 2008):

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy is a technique to remove a small number of key lymph nodes to evaluate cancer spread rather than removing most nodes in the area (axillary dissection). A radioactive suspension or a dye and often both materials are injected near the tumor site. The dye flows by the lymphatics toward the axillary nodes and is trapped by the first one or two lymph nodes, or the “sentinel” nodes, which are then removed for examination. Sentinel node biopsy may reduce the number of lymph nodes removed, reducing problems caused by lymphedema (see p. 780).

Adjuvant Therapy

Adjuvant therapy is supportive or additional therapy that follows the surgical procedure. Radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and immunotherapy are often recommended. The decision about whether to use adjuvant therapy is based on the woman’s age, the stage of the disease, the woman’s preference, and the hormone receptor status of the lesion. Radiation and chemotherapy are known to improve the chance of long-term survival after surgery for many cancers. Research is ongoing within many centers to determine the best uses for these adjuvant therapies for each individual woman when treating breast cancer. The nurse in oncology nursing must keep up with broad changes in adjuvant therapy as well as changes for each patient.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation uses high-energy rays to destroy cancer cells that remain in the breast, chest wall, and the underarm area after surgery. Skin in the treated area may have a reaction similar to sunburn. Lymphedema is more likely to occur if the axillary nodes are treated. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is a newer technology to deliver precise doses of radiation to the tumor or within the tumor limit adverse effects of radiation on normal tissue.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses a combination of drugs designed to kill proliferating cancer cells. Normal body cells, especially rapidly dividing cells such as those in the mouth, are also killed with chemotherapy but expected to regenerate. The drugs, doses, and schedule of administration are individualized for each woman based on factors such as type of cancer cells, age, hormone receptor status of malignant cells, and medications needed for nonmalignant disorders. Temporary loss of head and body hair is a side effect of many chemotherapeutics. Nausea, anemia, reduced clotting factors, and reduced immunity are other common side effects of many drugs.

Hormonal Therapy

Estrogen-blocking medications are prescribed because many breast tumors are estrogen-receptor positive, meaning that their growth is stimulated by estrogen. Estrogen-receptor–positive tumors may occur in premenopausal as well as postmenopausal women. Risks and benefits of proposed estrogen-blocking medications are discussed with the oncologist, particularly in women who have not reached menopause. Osteoporosis is a greater risk with estrogen-blocking medications.

Tamoxifen (Nolvadex) blocks estrogen by binding to estrogen receptors, thereby suppressing tumor growth by reducing the effects of estrogen. Hot flashes, vaginal dryness or an increased vaginal discharge, nausea, or anorexia may occur with tamoxifen therapy. Anastrozole (Arimidex), exemestane (Aromasin), and letrozole (Femara) are aromatase inhibitors with estrogen-blocking capabilities as they block conversion of androgens to estrogen.

The Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) research by the National Cancer Institute to compare effectiveness of tamoxifen and raloxifene (a drug to reduce osteoporosis) in prevention of breast cancer in high-risk women was completed in 2006. Results of the STAR research showed these drugs to be equally effective in preventing invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Those on raloxifene had a lower incidence of uterine cancer and less likelihood of developing blood clots than those on tamoxifen. See www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials for more information about drug trials for cancer therapy.

Immunotherapy

This is a biologically based therapy that targets specific cell pathways that promote cancer growth. Approximately 25% of women with breast cancer have tumors that overexpress the HER2/neu, a protein that promotes growth of breast cancer cells. Trastuzumab (Herceptin) is a monoclonal antibody given to reduce overexpression by this protein. Others being studied at this text revision are lapatinib (Tykerb), pertuzumab, and neratinib.

Breast Reconstruction

Timing

Breast reconstruction to normalize the body’s appearance is often an option for breast cancer treatment. Reconstruction options are discussed with the woman as other treatment plans are made. Immediate reconstruction appeals to many women because it quickly restores their breast contour and often makes them feel normal again. However, expected therapy for breast cancer may involve aspects for which later breast reconstruction is best. Some women prefer later reconstruction, even if not required, because it allows more time to learn options about reconstruction surgeries and about other ways they may enhance their appearance. The woman is able to physically heal from the mastectomy and to consider her personal values and desires about the added surgery.

Methods

Several methods of breast reconstruction are available. The tissue expansion method uses an empty silicone implant fitted with a valve that can be accessed by percutaneous needle puncture. The bag is filled with saline in small increments to slowly expand the tissue. When the desired volume is attained, the incision is reopened, the device is removed, and the expander is exchanged for the appropriate implant. In some models, only the valve must be removed and the expander serves as the permanent implant (ACS, 2009).

Tissue flap procedures move autogenous tissue from the back, abdomen, or buttocks to create a breast mound. Although these procedures do not always involve implants of a foreign substance as the tissue expansion method does, they involve at least two incisions: one at the breast and one at the site of the donor tissue. All women are not suitable for muscle flap grafts, particularly those with diabetes, connective tissue disorders, or smokers, because these procedures involve altering the blood supply to the transplanted tissue with the possibility of poor wound healing. Thin women may not have sufficient tissue for transplant to the breast (ACS, 2009).

Types of tissue flap procedures include:

Nipple/areola reconstruction improves the natural appearance in the reconstructed breast through a small skin graft. Tissue may be taken from the opposite nipple, from skin that covers the prosthesis mound, or from other body tissue. After the nipple has been reconstructed, tattooing promotes natural coloring to the nipple and areola (ACS, 2009).

Psychosocial Consequences of Breast Cancer

The time from discovery to treatment of breast cancer is the most stressful for many women. Factors that contribute to presurgery distress include a sense of uncertainty, inadequate information, the need to make difficult treatment decisions, and scheduling problems. Treatment usually involves consultations with multiple specialists, including a surgeon, a radiotherapist, a plastic surgeon, and a medical oncologist. When there are scheduling difficulties or conflicting opinions expressed by the health care team, the woman feels frustrated and confused.

Concerns frequently expressed during treatment for breast cancer include fear of recurrence and death, uncertainty about the quality of life, changes in body image, the effect on sexuality, and side effects of therapy. For many women, the knowledge that they will lose their hair as a result of chemotherapy creates one of the most difficult situations in therapy.

Breast cancer can have psychological consequences not only for women but also for their significant others. Difficulties reported include sleep disturbances, eating disorders, and problems with work responsibilities. The marital relationship may be strained, primarily in the areas of sexual relations and communication about matters related to the illness. Women and their partners sometimes differ in regard to how much they want to discuss the illness. Some women have a great need to discuss their diagnosis, treatment, and fears of recurrence. Other women and many men view discussion of such fears as negative thinking that delays adjustment.

Nursing Considerations

The woman who is diagnosed with breast cancer depends on nurses for emotional support and accurate information. The nurse must allow time for the woman to express her feelings and must convey a sense of empathic understanding by quiet presence, touch, and close attention to the woman’s concerns. Many women feel that they have lost control and that their lives have been taken over by cancer and the recommended treatments. They may have concerns about family relationships and how their sexual partner will respond. Each woman should be allowed to express her fears and worries. Use of communication techniques such as clarifying, paraphrasing, and reflecting feelings help the woman participate in her care.

The anxiety that most women experience is reduced when procedures and care are clearly understood. Preoperative teaching should include significant others, to increase their ability to support the woman. Teaching should include the length of the hospital stay and what will happen during that time. The nurse should describe the dressings, drainage tubes, and appearance of incisions for the breast procedure or procedures being planned (lumpectomy, mastectomy, reconstruction). Lymphedema of the arm on the side of the mastectomy is possible because of blocked lymphatic vessels, but it may not appear in the immediate postoperative period. Specific exercises such as arm lifts and pulley exercises may be necessary to promote flexibility in surgical areas.

Discharge teaching focuses on follow-up care and treatment. Some areas of concern are how to minimize the risk of wound infection, side effects of adjuvant therapy, and signs and symptoms that should be reported to the physician. Most women also benefit from support groups such as American Cancer Society’s Reach to Recovery (www.cancer.org) and community support groups often found in health care centers and churches. Survivors may find satisfaction in giving back to support others with breast cancer through these organizations.

Using nursing diagnoses to plan and implement care could ensure that care is complete. Relevant diagnoses might include:

Cardiovascular Disease

Heart disease is the leading cause of death for women in the United States, killing 26% of women who died in 2006 (CDC, 2010d). Cardiovascular diseases include disorders of the heart and blood vessels, such as myocardial infarction (MI), congenital abnormalities, and stroke. Those discussed here primarily relate to diseases of the blood vessels, particularly CAD. The topic is extensive, and only an overview will be presented in this text. A medical-surgical text should be consulted for more extensive information.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree