Newborn Feeding

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Identify the nutritional and fluid needs of the infant.

• Compare the composition of breast milk with that of formula.

• Describe the benefits of breastfeeding for the mother and the infant.

• Explain important factors in choosing a method of infant feeding.

• Explain the physiology of lactation.

• Describe nursing management of initial and continued breastfeeding.

• Explain nursing assessments and interventions for common problems in breastfeeding.

• Describe nursing assessments and interventions in formula feeding.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch/

Helping women choose and feel comfortable using a feeding method are important nursing contributions that require knowledge of the newborn’s nutritional needs and the techniques to meet those needs.

Nutritional Needs of the Newborn

Calories

The full-term newborn needs an average of 85 to 100 kcal/kg (39 to 45 kcal/lb) of body weight each day if breastfed and 100 to 110 kcal/kg (45 to 50 kcal/lb) if formula fed (Blackburn, 2013). Breast milk and formulas used for the normal newborn contain 20 kcal/oz.

During the early days after birth, infants may lose up to 10% of their birth weight because of normal loss of extracellular water and the consumption of fewer calories than needed (Halbardier, 2010; Jones, Hayes, Starbuck, et al., 2011). Newborns have a small stomach capacity and may fall asleep before feeding adequately. Capacity increases rapidly so that many infants take 60 to 90 mL (2 to 3 oz) by the end of the first week.

Infants usually regain the lost weight by 2 weeks of age (Keane, 2011). They should be evaluated for feeding problems if weight loss exceeds 7% to 8%, if loss continues beyond 3 days of age, or if the birth weight is not regained by 2 weeks of age in the term infant (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP] & American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2007). This information should be explained to parents.

Nutrients

The nutrients needed by the newborn are provided by carbohydrates, proteins, and fat in breast milk or formula. Full-term neonates digest simple carbohydrates and proteins well. Complex carbohydrates and fats are less well digested because of the lack of pancreatic amylase and lipase in the newborn. Vitamins and minerals are provided by both breast milk and formula.

Water

Because newborns lose water easily from the skin, kidneys, and intestines, they must have adequate fluid intake each day. The normal full-term newborn needs approximately 60 to 100 mL/kg (27 to 45 mL/lb) during the first 3 to 5 days of life, which should gradually increase to 150 to 175 mL/kg (68 to 80 mL/lb) a day (Halbardier, 2010). Breast milk or formula supplies the infant’s fluid needs. Additional water is unnecessary. See Box 23-1 for daily calorie and fluid needs of the newborn.

Breast Milk and Formula Composition

Breast Milk

Breast milk is species-specific (made for human infants) and offers many advantages over formula. The nutrients in breast milk are proportioned appropriately for the neonate and vary to meet the newborn’s changing needs. Breast milk provides protection against infection and is easily digested. Maternal immunoglobulins, leukocytes, antioxidants, enzymes, and hormones important for growth are present in breast milk but are not available in formula.

Changes in Composition

The composition of breast milk changes in three phases: Lactogenesis (the production of milk) stages I, II, and III.

Lactogenesis I

Lactogenesis I begins during pregnancy and continues during the early days after giving birth. At this time the breast secretes colostrum—a thick, yellow substance. Colostrum is higher in protein and some vitamins and minerals than mature milk. It is lower in carbohydrates, fat, lactose, and some vitamins. It is rich in immunoglobulins, especially secretory IgA, which helps protect the infant’s gastrointestinal tract from infection. Colostrum helps establish the normal flora in the intestines, and its laxative effect speeds the passage of meconium.

Lactogenesis II

Lactogenesis II begins at 2 to 3 days after birth. Transitional milk, milk that gradually changes from colostrum to mature milk, appears over approximately 10 days (Lawrence & Lawrence, 2011). The amount of milk increases rapidly as the milk “comes in.” Immunoglobulins and proteins decrease, and lactose, fat, and calories increase. The vitamin content is approximately the same as that of mature milk.

Lactogenesis III

Mature milk replaces transitional milk during lactogenesis III. Because breast milk is bluish and not as thick as colostrum, some mothers think their milk is not “rich” enough for their infants. Nurses should explain the normal appearance of breast milk. Mature milk contains approximately 20 kcal/oz and nutrients sufficient to meet the infant’s needs. It continues to provide immunoglobulins and other antibacterial components. Discussions of breast milk and its contents refer to mature milk unless otherwise stated.

Nutrients

Protein

The concentrations of amino acids in breast milk are suited to the infant’s needs and ability to metabolize them. Breast milk is high in taurine, which is important for bile conjugation and brain development. Breast milk is low in tyrosine and phenylalanine, corresponding to the infant’s low levels of enzymes to digest them (Lawrence & Lawrence, 2011). The proteins produce a low solute load for the infant’s immature kidneys.

Casein and whey are the proteins in milk. Casein forms a large insoluble curd that is harder to digest than the curd from whey, which is very soft (Riordan, 2010). Breast milk is easily digested because it has a high ratio of whey to casein, especially in early lactation. Commercial formulas must be adapted to increase the amount of whey so the curd is more digestible. Infants use almost all of the protein in human milk but pass a large amount of protein from formulas in the stools (Eiger, 2009).

Allergy to cow’s milk is the most common allergy in infants (Riordan, 2010). Because breast milk is made for the human infant, it is unlikely to cause allergies. Infants with a family history of allergies are less likely to develop them if they are breastfed (Lawrence & Lawrence, 2011). Although breast milk does not cause allergies, allergenic foods the mother has eaten may pass to her milk. If the infant reacts to the mother’s diet, the offending food should be identified and eliminated. Foods in the mother’s diet that may cause a problem for some infants include cow’s milk or milk products, chocolate, cola, corn, citrus fruit, wheat, and peanuts (Bronner, 2010).

Studies have been inconclusive in determining if avoiding common antigens in the mother’s diet will protect against allergies in the infant. General recommendations are that the infant be exclusively breastfed for at least 4 months and that allergic foods be avoided by the mother if her infant younger than 6 weeks of age has colic (List & Vonderhaar, 2010).

Carbohydrate

Lactose is the major carbohydrate in breast milk. It improves absorption of calcium and provides energy for brain growth. Other carbohydrates in breast milk increase intestinal acidity and impede growth of pathogens (Riordan, 2010).

Fat

Fat provides half of the calories in breast milk (Kleinman, 2009). The amount of fat in breast milk varies during the feeding, between feedings, and on the same or different days. More fat is present in the hindmilk—the milk produced at the end of the feeding. Hindmilk helps the infant gain weight.

Triglycerides form the majority of fat content. Cholesterol and essential fatty acids such as long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and arachidonic acid (ARA), important for vision and brain and nervous system development, are also present. The fat in breast milk is more easily digested by the newborn than that in cow’s milk.

Vitamins

Vitamin A, E, and C are high in breast milk. The vitamin D content of breast milk is low, and daily supplementation with 400 IU is recommended within the first few days of life for all infants whether breastfed or formula fed (Kleinman, 2009; Wagner, Greer, & AAP Section on Breastfeeding and Committee on Nutrition, 2008). Breastfeeding infants who are not exposed to the sun and those with dark skin are particularly at risk for insufficient vitamin D. The presence of water-soluble vitamins varies according to the mother’s intake. The infant of a vegan mother may need supplementation with vitamin B12.

Minerals

Although iron in breast milk is lower than that in formula, it is absorbed five times as well, and breastfed infants are rarely deficient in iron (Riordan, 2010). The full-term infant who is breastfed exclusively maintains iron stores for the first 6 months of life (Lawrence & Lawrence, 2011). Generally iron is added when the infant begins solids at 6 months. Preterm infants need iron supplements earlier. All formula-fed infants should receive formula fortified with iron (AAP & ACOG, 2007; Holt, Wooldridge, Story, et al. , 2011).

Like iron, calcium is low in breast milk, but it is absorbed better than that in cow’s milk. Phosphorus is higher in cow’s milk, but this may interfere with calcium absorption. Sodium, calcium, and phosphorus are higher in cow’s milk than in human milk. There is no need to give fluoride supplements to infants younger than 6 months of age. After 6 months, fluoride may be given to formula-fed infants if water supplies do not contain sufficient fluoride (Kleinman, 2009).

Enzymes

Breast milk contains enzymes that aid in digestion. Pancreatic amylase, necessary to digest carbohydrates, is low in the newborn, but present in breast milk. Breast milk also contains lipase to increase fat digestion.

Infection-Preventing Components

Substances in breast milk, such as bifidus factor, leukocytes, lysozymes, and lactoferrin, help prevent infection in the infant. Immunoglobulins are present in highest amounts in colostrum but are present throughout lactation. Secretory IgA produced in the breasts helps prevent viral and bacterial invasion of the intestinal mucosa, resulting in fewer intestinal infections. Infants who are breastfed have an decreased incidence of respiratory, gastrointestinal, and urinary tract infections, otitis media, asthma, diabetes, necrotizing enterocolitis, some cancers, obesity, sudden infant death syndrome, and infant mortality (Lawrence & Lawrence, 2011).

Effect of Maternal Diet

Although the fatty acid content of breast milk is influenced by the mother’s diet, malnourished mothers’ milk has about the same amounts of total fat, protein, carbohydrates, and most minerals as milk from those who are well nourished. Levels of water-soluble vitamins in breast milk, however, are affected by the mother’s intake and stores (Lawrence & Lawrence, 2011). It is important that breastfeeding women eat a well-balanced diet to maintain their own health and energy levels (see Nutrition for the Lactating Mother in Chapter 14 p. 293.)

Formulas

Commercial formulas are produced to replace or supplement breast milk. They are sometimes called “breast milk substitutes” or “artificial breast milk” because manufacturers must adapt them to correspond to the components in breast milk as much as possible. An exact match is impossible, however. A variety of formulas that differ in price and ingredients is available.

Cow’s Milk

Unmodified cow’s milk (whole milk, lowfat milk, or fat-free milk) is not recommended for infants younger than 12 months. It contains too much protein, potassium, chloride, and sodium; lacks enough fatty acids, iron, and vitamin E; and may cause gastrointestinal bleeding and anemia. It also causes the renal solute load to be too high (Kleinman, 2009).

Modified cow’s milk is the source of most commercial formulas. Manufacturers specifically formulate it for infants by making changes in the protein and fat and adding vitamins and other nutrients to simulate the contents of breast milk. Formula with added iron should be used for all infants receiving formula.

Formulas for Infants with Special Needs

Infants with galactosemia, lactase deficiency, or those whose families are vegetarians may receive soy formula. As many as half of infants allergic to cow’s milk are also allergic to soy protein (Nguyen & Kerner, 2009). Protein hydrolysate formulas are better tolerated by infants with allergies. The protein in these formulas is treated to make it less allergenic. The formulas are also used for infants with malabsorption disorders. Amino acid formulas are used for allergic infants who do not thrive on extensively hydrolyzed protein formulas.

Lactose-free formula uses primarily glucose instead of lactose for infants who do not tolerate lactose. Low-phenylalanine formulas are needed for infants with phenylketonuria, a deficiency in the enzyme to digest phenylalanine found in standard formulas. The preterm infant may require a more concentrated formula with more calories in less liquid. Modifications of other nutrients are also made. Human milk fortifiers can be added to breast milk to adapt it for preterm infants.

Considerations in Choosing a Feeding Method

Many women decide on a feeding method well ahead of the birth. Nurses can help undecided parents choose a method and gain confidence in feeding their infants. For those who are undecided, nurses should explain the many benefits of breastfeeding for the mother and the infant.

However, nurses must be sensitive to mothers’ feelings about feeding. Although nurses should encourage breastfeeding as the best method of feeding in most circumstances, they should be supportive of the mother’s chosen method once the decision is made. The early days of parenting are a vulnerable time for new mothers, and the nurse’s encouragement and teaching about the chosen feeding method are essential.

Breastfeeding

Mothers choose breastfeeding because it offers many advantages for the mother and the infant (Box 23-2). The AAP recommends that infants receive only breast milk for approximately the first 6 months. Breastfeeding should continue until the infant is at least 12 months old with the addition of complementary foods (AAP, 2012; Kleinman, 2009). Breastfeeding and support to help mothers achieve it are also recommended by the American Dietetic Association (2009) and the U.S. Surgeon General (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2011).

A goal set by the USDHHS for 2020 is for 81.9% of all infants to be breastfed at some time, for at least 60.5% to be breastfeeding at 6 months, and 34.1% at 1 year. Additional goals are to increase the number of mothers who exclusively breastfeed their infants through 3 months to 44.3% and through 6 months to 23.7% (USDHHS, 2010).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that in 2011, 75% of infants were ever breastfed. The report also reveals that 44% of mothers breastfed their 6-month-old infants, and 24% of mothers continued breastfeeding their 12-month-old infants. Exclusive breastfeeding rates were 35% at 3 months and 15% at 6 months. These statistics show a gradual but steady increase over previous years, but continued improvement is needed (CDC, 2011).

In an effort to promote breastfeeding, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the U.S. Surgeon General advocate that birth facilities become certified as “baby-friendly” hospitals, with policies to actively encourage breastfeeding. Guidelines to becoming certified as a baby-friendly hospital emphasize education of staff and parents about breastfeeding, early initiation of breastfeeding, demand feedings, avoidance of formula and pacifiers, and rooming-in. Unfortunately, less than 5% of U.S. hospitals are certified as baby-friendly (CDC, 2011a; USDHHS, 2011a). (More information is available at http://babyfriendlyusa.org.)

Formula Feeding

Parents choose formula feeding for many reasons. Some women are embarrassed by breastfeeding, seeing the breasts only in a sexual context. Many mothers have little experience with family or friends who have breastfed infants. The woman’s partner or mother may not be supportive of breastfeeding. Occasionally a woman requires medications that might harm the infant. A frequent reason that mothers choose formula feeding instead of breastfeeding is a lack of understanding and education about the two methods.

Combination Feeding

Some parents prefer a combination of breastfeeding and formula feeding. Unless medically indicated, it is best to delay giving formula until lactation has been well established at 3 to 4 weeks of age. Giving breastfeeding infants formula leads to a decrease in breastfeeding frequency and milk production, making successful breastfeeding less likely (AAP & ACOG, 2007). However, if the mother chooses to feed both breast milk and formula, the nurse should educate and support her so the infant receives the benefits of breast milk at least part of the time.

A mother may give a bottle daily or only occasionally, such as when a baby-sitter is with the infant. Some mothers feel this allows them to be away from the infant for longer periods of time yet allows the closeness with the infant they enjoy, as well as the physical advantages of breastfeeding, to continue. Mothers may choose to use breast milk or formula for occasional bottle feedings.

Factors Influencing Choice

Many factors influence a woman’s choice of feeding method. These factors must be considered when educating women about their choices.

Support from Others

The decision to breastfeed is strongly influenced by the woman’s family and friends. She is likely to ask for advice from her partner first, followed by advice from her mother, family, and friends (USDHHS, 2011). The woman with little support or with active discouragement from her family will probably have a more difficult time nursing. Advice from friends who have breastfed may also influence the mother’s decision.

Involvement of the father in infant care is important for some families, and some may feel it is only possible with feedings. Nurses can suggest other infant care measures, such as holding, rocking, and bathing, which fathers can enjoy. Educating family members about the advantages of breastfeeding and how to deal with problems may lead to their encouragement and support.

Prenatal classes that include breastfeeding information may help a woman decide to breastfeed and may help her develop confidence that she will be successful. Educating fathers about the benefits of breastfeeding, as well as techniques for coping with any difficulties that might occur, is important. Fathers should also attend the classes so they can provide increased support based on their knowledge. Both prenatal classes and new mother support groups led by lactation consultants are associated with higher breastfeeding rates at 6 months postpartum (Rosen, Krueger, Carney, et al., 2008).

Encouragement from the woman’s health care provider may be a powerful influence in the woman choosing to breastfeed (Newton, 2007). The support the mother receives from the nursing staff plays a significant part in whether she feels comfortable with her chosen feeding method. Mothers who do not feel confident in their ability to breastfeed before they leave the birth facility are less likely to continue breastfeeding if they encounter difficulties at home.

Other support also may be important. Doulas, trained lay-women who make home visits to assist women with breastfeeding after discharge, have been shown to increase the rate of breastfeeding at 6 weeks postpartum (Nommsen-Rivers, Mastergeorge, Hansen, et al., 2009). One study of African-American women found that breastfeeding self-efficacy, a woman’s belief that she will be able to breastfeed successfully, was associated with a longer period of breastfeeding and more exclusive breastfeeding at 1 and 6 months postpartum (McCarter-Spaulding & Gore, 2009).

Culture

Cultural influences may dictate decisions about how a mother feeds her infant. For example, many Mormon women believe that breastfeeding is an important part of motherhood. Muslim women often breastfeed for the first 2 years. Women who are most likely to breastfeed are Asian, Pacific Islander, or Hispanic. Those with the lowest breastfeeding rates include women who are non-Hispanic Black (USDHHS, 2011).

Immigrants to the United States often would breastfeed infants if they were still in their own countries. For example, in Russia, women are expected to breastfeed, and formula is not available in birth houses (Callister, Getmanenko, Garvrish, et al., 2007). Hispanic women who are new immigrants are more likely to begin breastfeeding and continue for a longer period than more acculturated immigrants (Gill, 2009). Some of these women may think that formula is the preferred method of feeding in the United States because it is available in the hospital. Nurses must emphasize the superiority of breastfeeding and encourage these women to continue their cultural tradition of breastfeeding.

Nurses should be particularly watchful for ways to help mothers from other cultures who might wish to breastfeed but fail to do so because of lack of support. Some Asian and Latina mothers give their infants formula while in the birth facility and do not begin to breastfeed until at home. This practice may be caused by modesty about nursing in front of others in the birth facility, as well as lack of understanding about the value of colostrum. Women in some cultures believe that colostrum may be “spoiled” because it has been in the breasts for a long time. They may express colostrum and discard it before they begin to breastfeed the infant. Education from nurses can help mothers understand the importance of giving colostrum and that much of the milk is produced as the infant is suckling (feeding at the breast).

Rituals may be important in some cultures. In the Philippines, the ritual of lihi, stroking the mother’s breasts with papaya leaves and sugar cane stalks ensures a good supply of rich milk (Riordan, 2010). Hispanic women may believe that they can transmit negative emotions to their breastfeeding infants. Navajo women believe they pass maternal attributes and model good behavior by breastfeeding (Kleinman, 2009).

Employment

Women should be encouraged to continue breastfeeding when they return to work. Because of the decreased incidence of illness in breastfed infants, the mother is less likely to miss work to take care of a sick infant. This is an advantage for the employer as well as the breastfeeding family.

Unfortunately, returning to work or school is a major cause of discontinuation of breastfeeding. The mother may choose formula from the beginning, plan a short period of breastfeeding before weaning the infant to formula, or use a combination of breastfeeding and bottle feeding with breast milk or formula. Nurses who provide practical information about options, breastfeeding and working, breast pumps, and storage of breast milk help a mother continue breastfeeding for a longer period. Referral to a lactation consultant can provide a mother with continued education and support after she goes home.

Staff Knowledge

It is important that all birth facility staff members have education about how to help women breastfeed and do not provide inaccurate or conflicting information to new mothers. Educational programs are effective in helping to ensure that all staff have the same basic knowledge and skills to help breastfeeding mothers. Programs may involve formal classes, protocols, and self-paced learning modules (Bernaix, Beaman, Schmidt, et al., 2010; Mellin, Poplawski, & Gole, 2011).

Other Factors

Other factors may also influence a woman’s decision. Her knowledge and past experience with infant feeding are important. Women who receive assistance from the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), those without some college education, and those who live in the southeastern United States have lower breastfeeding rates than other women (USDHHS, 2011). One study found that women were more likely to breastfeed exclusively in the hospital if they began prenatal care in the first trimester and had expressed an intention during pregnancy to breastfeed exclusively. Women who were overweight or obese were half as likely to breastfeed exclusively during the hospital stay (Tenfelde, Finnegan, & Hill, 2011).

Normal Breastfeeding

Breast Changes during Pregnancy

Breast changes begin early in pregnancy (see Chapters 11 and 13 and Figures 11-8 and 13-3). The ducts, lobules, and alveoli develop in response to estrogen, progesterone, prolactin, and human chorionic somatomammotropin (hCs) (also called human placental lactogen). Prolactin levels are high, but milk production is prevented by estrogen, progesterone, and hCs, which inhibit breast response to prolactin. Changes, such as increase in breast size, indicate that the breasts are responding adequately to hormonal stimulation to prepare for lactation. Colostrum is present from 12 to 16 weeks of pregnancy (Janke, 2008).

Milk Production

Milk is produced in the alveoli of the breasts through a complex process by which materials from the mother’s bloodstream are reformulated into breast milk. The milk is ejected from the secretory cells of the alveoli into the alveolar lumen by contraction of the myoepithelial cells. It travels through the lactiferous ducts to the nipple. The infant compresses the areola during nursing to eject a stream of milk through pores in the nipple. Although there is a small amount of milk in the breasts at the beginning of feedings, most of the milk is made during infant suckling (Brozanski & Bogen, 2007).

Hormonal Changes at Birth

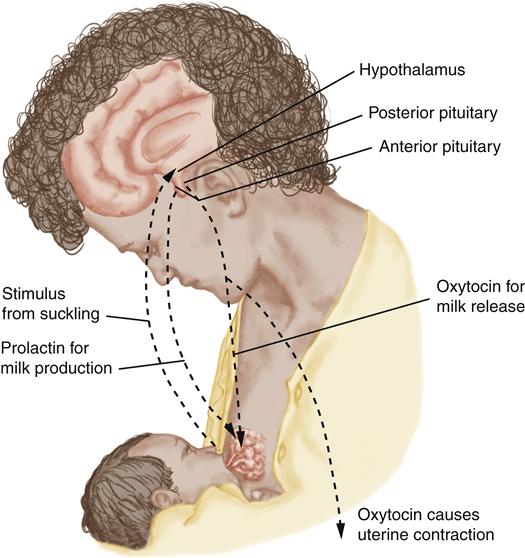

Prolactin

At birth, loss of placental hormones results in increasing levels and effectiveness of prolactin to stimulate milk production. Suckling and the removal of colostrum or milk cause continued increased levels of prolactin. Prolactin is secreted at highest levels with suckling and during the night (Lawrence & Lawrence, 2011). Levels are high during the early months and then gradually decrease until weaning.

Oxytocin

Oxytocin, the pituitary hormone, increases in response to nipple stimulation and causes the milk-ejection reflex, or let-down reflex, the release of milk from the alveoli into the ducts. The milk-ejection reflex occurs intermittently during each feeding. Mothers may have a tingling sensation of the breast when the let-down occurs.

When mothers see, hear, or think about their infants, they often have an increase in oxytocin, bringing about a let-down of milk. Pain or lack of relaxation can decrease oxytocin release. Oxytocin also causes the uterine contractions mothers may feel at the beginning of nursing sessions. These contractions are beneficial because they hasten involution of the uterus (Figure 23-1).

Continued Milk Production

The amount of milk produced depends primarily on adequate stimulation of the breast and removal of the milk. This “supply-and-demand” effect continues throughout lactation—that is, increased demand with more frequent and longer nursing results in more milk available.

If milk (or colostrum) is not removed from the breasts, components in the milk cause a feedback that decreases prolactin secretion and milk production. Milk in the ducts is eventually absorbed, the alveoli become smaller, the secretory cells return to a resting state, and milk production ends.

Preparation of Breasts for Breastfeeding

Little preparation is needed during pregnancy for breastfeeding. The mother should avoid soap on her nipples to prevent removal of the natural protective oils from the Montgomery tubercles of the breasts. The use of creams and nipple rolling, pulling, and rubbing to “toughen” nipples do not decrease nipple pain after birth and may cause irritation or uterine contractions from release of oxytocin.

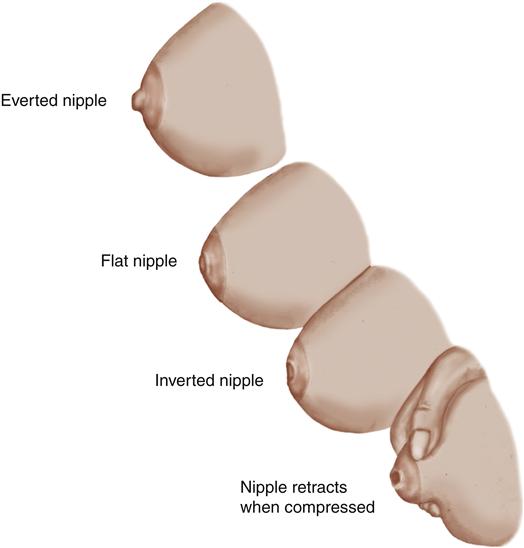

The breasts should be assessed during pregnancy to identify flat or inverted nipples (Figure 23-2). Normal nipples protrude. Flat nipples appear soft, like the areola, and do not stand erect unless stimulated by rolling them between the fingers. Inverted nipples are retracted into the breast tissue. Both conditions may make it difficult for infants to draw the nipples into the mouth. Some nipples appear normal but draw inward when the areola is compressed in the infant’s mouth. Compressing the areola between the thumb and forefinger determines whether the nipple projects normally or becomes inverted. Nipples that appear flat or inverted early in pregnancy may be improved near term (Riordan & Wambach, 2010).

The helpfulness of breast shells for flat or inverted nipples is debated. Some authors find them helpful for some women, and others feel they decrease motivation to breastfeed and do not improve nipple eversion (Lawrence & Lawrence, 2011; Riordan & Wambach, 2010). The dome-shaped devices are worn during the last weeks of pregnancy and between feedings after birth. The shells are placed in the bra with the opening over the nipple. They exert slight pressure against the areola to help the nipples protrude. A breast pump used just before feedings to help bring the nipples out may be more effective.

Nursing Care

Breastfeeding

Assessment

Assess the mother and the infant during the breastfeeding process.

Maternal Assessment

Breasts and Nipples

Assess the condition of the breasts and nipples and the mother’s knowledge about breastfeeding to determine her need for assistance. Examine the breasts and nipples during late pregnancy to identify problems that might interfere with feeding. Assess the protrusion of the nipples to identify flat or inverted nipples.

After birth, palpate the breasts with each postpartum assessment to see if they are soft, filling, or engorged. Soft breasts feel like a cheek. If milk is beginning to come in, the breasts may be slightly firmer, which is charted as “filling.” Engorgement is congestion and increased vascularity, edema from obstruction of drainage of the lymphatics, and accumulation of milk, as lactation is established. Engorged breasts may be hard and tender, with taut, shiny skin. Engorgement often is not seen until after discharge. Note any redness, tenderness, or lumps within the breasts. The nipples may be red, bruised, blistered, fissured, bleeding, or tender. Ask about nipple tenderness. Evaluate breastfeeding techniques if the mother is having problems with her nipples.

Knowledge

The mother breastfeeding for the first time may have many questions and may need substantial guidance during her first attempts. If she has nursed before, she may have a better understanding of breastfeeding but may have forgotten some aspects and have questions.

Assessment of Infant Feeding Behaviors

Before initiating a breastfeeding session, assess the infant’s readiness for feeding (Box 23-3). The infant should be awake and alert. Sucking on the hands, rooting when the cheek or side of the mouth is touched, smacking the lips, and hand-to-mouth movements are hunger cues. Infants should be fed before they begin crying, which is a late sign of hunger. Crying infants must be calmed before they are ready to feed. Continue to assess for signs of problems throughout the feeding.

LATCH Scoring Tool

Assessing the infant’s latch or attachment to the breast is important. The LATCH breastfeeding assessment tool may be helpful (Jensen, Wallace, & Kelsay, 1994). The tool assigns a score of 0 to 2 in five areas. A score of 7 or less indicates the mother needs more assistance in feeding.

Nursing Diagnosis and Planning

Women with and without experience often need information to have a successful breastfeeding experience. A woman’s confidence in her ability to breastfeed may be an important determinant of her success. Therefore nurses should help women increase their confidence and help prevent early weaning by using the nursing diagnosis:

Expected Outcomes

The infant will breastfeed using nutritive suckling for 10 to 15 minutes or more on each breast for most feedings before discharge. The mother will demonstrate breastfeeding techniques as taught and will verbalize satisfaction and confidence with the breastfeeding process before discharge.

Interventions

Interventions are centered on teaching that nurses should provide to all breastfeeding mothers and their support persons. These techniques should be adapted as appropriate for mothers who have some knowledge of breastfeeding but need review or clarification.

Assisting with the First Feeding

The first feeding should take place within the first hour after birth if both mother and infant are in stable condition. Breastfeeding within the first hour is associated with a higher breastfeeding rate at 2 to 4 months after birth than later breastfeeding (Schanler, 2009). Early breastfeeding provides stimulation of milk production and improved suckling and may increase the duration of breastfeeding. The mother may need assistance in positioning herself and the infant and a demonstration of how to hold the breast. Stay with the mother during the first few feedings to help her with problems that may arise. After the first feedings, check back frequently to answer questions.

Teaching Feeding Techniques

Position of the Mother and Infant

Make the mother comfortable before beginning the feeding. Provide pain medications, if necessary. Provide privacy and prevent interruptions so she can concentrate. Breastfeeding mothers most often use the cradle, football or clutch, and cross-cradle holds and the side-lying position (Figures 23-3 through 23-6). To increase her comfort, position pillows behind the mother’s back, over an abdominal incision, or to support her arms. Her shoulders should be relaxed, and she should not be hunched over.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree