Medication Administration and Safety for Infants and Children

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Describe different methods of administering medications to children.

• List the advantages and disadvantages of each route of administering medication to children.

• Describe the physiologic differences between children and adults that affect medicating a child.

• Describe quality and safety issues associated with medication administration in children.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch

Medicating infants and children is one of the nurse’s most important responsibilities. The nurse plays a key role in administering medications, supporting the child and family during the experience, and teaching the child and parents about pharmacologic aspects of the child’s care. Although physicians or nurse practitioners prescribe medications, the nurse or caregiver is responsible for their administration. The nurse has a legal responsibility to administer medications safely and accurately. Safe administration of medications to children requires an understanding of the dosages of the medications used for children and the expected actions, possible side effects, and signs of adverse reactions or toxicity. Nurses should use reliable sources of information (e.g., pharmacists, drug handbooks, hospital formularies) when administering medications and should ask the prescribing practitioner questions about orders that are unclear, inaccurate, or potentially incorrect before administering the medication.

Giving medications to children requires special skills. To gain the child’s cooperation and to administer the medication in the least traumatic manner, the nurse needs to understand the physical characteristics and psychological needs of children at each developmental level. The nurse should use developmentally appropriate strategies to manage children’s fears, prevent injury, and enhance coping.

It is vitally important to provide parents with information about medications used in their child’s treatment and to encourage parents to support their child during experiences related to medications. Involving parents in the task of eliciting their child’s cooperation not only makes the job easier but also gives the family a sense of self-management and control. If the parents will need to administer medications to their child at home, the nurse ensures that the parents receive complete instructions and correctly demonstrate medication administration techniques before the child is discharged.

Adherence to taking the full course of a medication to treat an acute illness or following a medication regimen for chronic illness management continues to be a challenge for children, adolescents, and their families (Matsui, 2007; Rapoff & Lindsely, 2007). Barriers to effective adherence to medications include cost, medication taste, inability to read or comprehend directions, misunderstanding about the correct dose or number of times to take the medication, and lack of understanding about the illness and need for the medication (Gerald, McClure, Mangan, et al., 2009; Mears, Charlebois, & Holl, 2006).

Factors that improve medication adherence include allowing adequate time for the health care provider to educate the parent and child, continuity of care, availability of the health provider to answer questions about the medication, a medication schedule that fits the family’s lifestyle, low cost, oral route, palatable taste for oral drugs, and low potential for side effects. Any medication regimen should consider the child’s developmental needs. Further, a variety of administration, educational, and behavioral strategies need to be used; these include simple dosing schedules that correlate with daily routine, explanation of treatment goals, negotiation of treatment regimens, teaching ways to minimize side effects, supervised practice of skills by child and family, providing cues for monitoring adherence, promoting adherence through positive reinforcement, and encouraging self-management for older children and adolescents (Kamps, Rapoff, Roberts, et al., 2008; Rapoff & Lindsely, 2007).

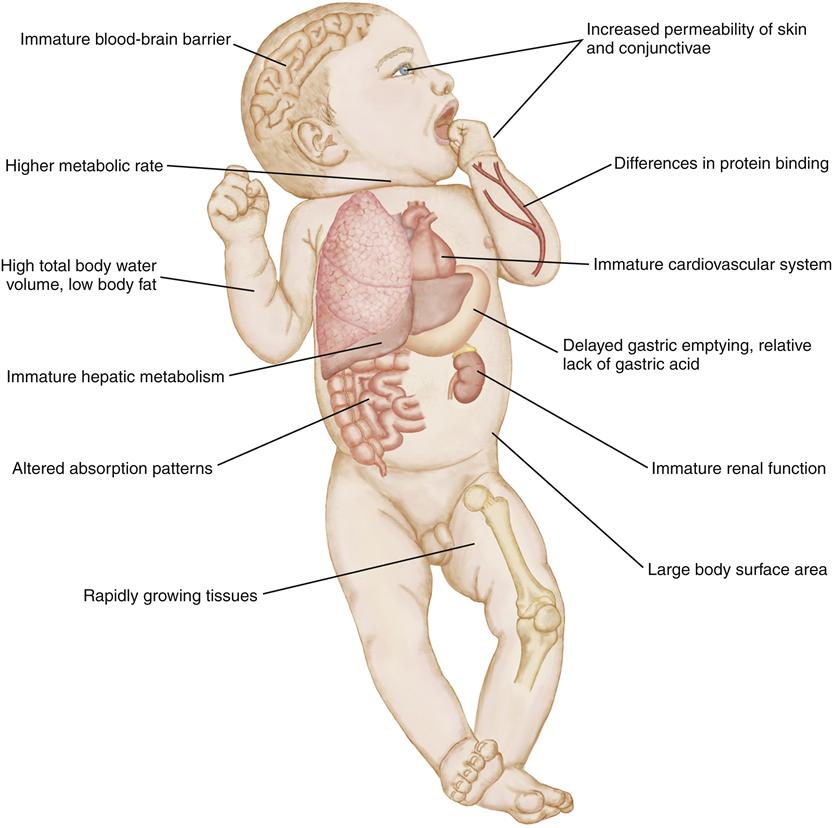

Pharmacokinetics in Children

An understanding of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics guides appropriate interventions in children. Pharmacokinetics refers to the actions of a drug (e.g., movement, biotransformation) within the human body over time, and pharmacodynamics is the behavior of a drug as it interacts with the biochemical and physiologic milieu of the body. The pharmacokinetic actions of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion are influenced by the physiologic environment in which the drug moves, and this environment differs between adults and children (Figure 38-1). The physiologic differences in body systems are most striking in the neonate.

Absorption

Oral Route

When a medication is given orally, several factors influence its absorption along the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Because most medication absorption occurs in the small intestine, the drug must reach that location in a form suitable for maximum absorption. Four factors influence this process.

Gastric Acidity

The gastric secretions of infants are less acidic than those of older children or adults. Secretions slowly increase in acidity during the first 2 years of life. Children, particularly infants and toddlers, tend to eat more frequently than adults and thus often have food and digestive enzymes present in their stomachs. Formula or milk can increase the alkalinity of gastric secretions, decreasing the absorption of medications that require a more acidic environment, and enhancing the absorption of medications that require a more alkaline milieu. These factors can greatly affect serum drug levels.

Gastric Emptying

Gastric emptying is intermittent and unpredictable in infants; it does tend to be slower than in older children. This slower pace can prolong the time it takes a medication to reach the intestinal absorption site.

Gastrointestinal Motility

Depending on whether an infant or young child has eaten recently, peristaltic activity in the intestine can be faster or slower than in an older child or adult. Infants up to 8 months of age tend to have prolonged motility. Certain adverse health conditions, such as diarrhea, can alter intestinal motility by increasing peristalsis. The longer the transit time in the intestine, the more medication that is absorbed. Conversely, a shortened transit time decreases medication absorption.

Enzyme Activity

Pancreatic enzyme activity also is variable in infants for the first 3 months of life as the GI system matures. Medications that require specific enzymes for dissolution and absorption might not be converted to a suitable form for intestinal action.

Other Routes

Adequate absorption of medication administered intravenously (IV) depends on adequate peripheral perfusion. Medications given IV are immediately available for absorption into the child’s bloodstream. When compared to an adult, a child’s peripheral circulation is less reliable and more responsive to environmental changes. As a result, vasoconstriction or vasodilation can occur and alter the absorption of a parenteral medication. Also, the cardiovascular system is less able to accommodate large or rapid changes in volume, and fluid overload can result from poorly controlled IV infusions. A child has a smaller muscle mass than an adult; an infant’s body weight is about 25% muscle, compared to an adult whose body weight is about 40% muscle. Thus, infants have fewer sites available for intramuscular (IM) injections. Further, blood flow to muscle tissue can be erratic in young children, and this can increase or decrease the absorption of IM medications.

Infants and young children have a thinner outer skin layer (stratum corneum) and a larger body surface area (BSA) to weight ratio. Infants have more skin surface area relative to weight than adults and thus the absorption of topical medications is much greater than adults. Skin pH varies with age and can affect the absorption of topical medications as well. Children also tend to be more prone to skin irritation, resulting in more frequent contact dermatitis and other allergic reactions. Irritated or open skin can enhance the absorption of topical medications.

Distribution

Distribution refers to the general and specific concentration of the medication in body fluids and tissues. Medications are distributed to body tissues through blood and body fluids.

Differences in Body Fluids

Fluid differences between children younger than 2 years and older children must be considered when the nurse determines dosages of medication. The body fluid content ranges from 75% of body weight in infants to 60% of body weight in children 2 years and older (see Chapter 40). Because of their greater fluid volume per weight, children need a higher dose per kilogram of a water-soluble medication to achieve the desired distribution effects.

A higher percentage of the young child’s body fluid is located in the extracellular fluid compartment. During certain illnesses, this extracellular fluid can be lost rapidly, causing fluid depletion. It is important to adjust medication dosages accordingly in an ill infant or young child to avoid overdosing or underdosing.

Differences in Fat Percentages

Percentages of fat also change as the child grows. Fat makes up about 16% of an infant’s weight, although total body fat varies from child to child. The percentage of fat per body weight is increased in a 1-year-old as compared to an infant, but then decreases in a preschool child. The percentage of body fat affects the distribution of fat-soluble medications in children. Because body fat must be saturated with a fat-soluble medication before the drug becomes detectable in the blood, dosages often must be varied to achieve desired effects.

Differences in Proteins

Medications bind to plasma proteins, mainly albumin, for distribution. Only free, unbound medication can be absorbed by the body. Because preterm and newborn infants have lower levels of plasma proteins than do older children, more unbound drug circulates. This alters the amount of medication needed to maintain a therapeutic drug level and may increase the infant’s vulnerability to adverse drug effects.

Blood-Brain Barrier

The blood-brain barrier does not fully mature until a child is about 2 years old. This immaturity causes the barrier to be less selective, allowing the distribution of medications into the central nervous system. As a result, encephalopathy can occur with some medications.

The relative immaturity of the neurologic system also can lead to paradoxical effects from certain medications. For example, medications that normally cause sedation in adults may have the opposite effect in some children, causing hyperactivity.

Metabolism

Most medications are metabolized in the liver. Metabolic enzyme systems are less mature in newborn and premature infants, so they may not properly metabolize all the medication in a given dose. Older infants, toddlers, and preschoolers metabolize certain drugs (e.g., pain medications) more rapidly than adults. For this reason, larger dosages or more frequent administration of certain drugs might be needed for young children to achieve desired therapeutic outcomes.

Excretion

Most medications are excreted through the renal system. A newborn’s renal system is immature with a lower glomerular filtration rate and less efficient renal tubular function. Adult levels of renal function are not reached until between 1 and 2 years of age. Infants and young children also are unable to concentrate urine as compared to older children or adults (see Chapter 44).

Because of renal immaturity, adequate quantities of a given medication may not be filtered out of circulating blood and excreted in the urine (the primary method of medication excretion). As a result, a medication can circulate longer and reach toxic levels in the blood. Fluid volume loss (dehydration) can also decrease a child’s ability to excrete medications and can adversely affect serum drug levels.

Concentration

To safely administer medications to children, nurses need to know the concentration of certain medications in the bloodstream. Maintaining serum levels within a safe, therapeutic range maximizes the desired effect of a medication while reducing the risk of toxicity. With certain medications, the physician will order peak and trough serum levels to be measured in order to monitor medication concentration. The peak concentration is not necessarily the highest concentration, but the concentration of the medication after it has been distributed. A medication reaches its peak concentration at a specified time after the medication has been administered.

The medication trough is the level at which the serum concentration is lowest. Trough levels usually are obtained just before the next medication dose is scheduled to be administered. Knowing the peak and trough range for a specific medication will assist the nurse to accurately assess the child’s response, and potential for toxic effects.

Psychological and Developmental Factors

Growth and developmental principles and differences among age-groups must always be considered when medicating a child. Eliciting support from the parents often will help ease the child’s concerns and fears.

Restraints are seldom necessary for administration of medications. It is appropriate to ask a staff member to assist the child to hold still during an injection because the child’s movements could jeopardize safe administration of the medication (see Chapter 37). Parents may help to distract and comfort their child.

Honesty, praise, and reward are important elements of the medication administration process. The nurse should give honest explanations and tell the child if a medication may have an unpleasant taste, when a procedure will be painful or uncomfortable and approximately how long the pain will last, and what the child can do to help during medication administration (e.g., not move, hold the cup). Terminology that is familiar and understandable (e.g., “pinching” or “stinging”) should be used.

Rewards following a procedure often serve to encourage the child and reinforce appropriate behavior. The reward should be safe and appropriate for the child’s age. Stickers are usually a good choice for younger children. For an older child, providing time for a favorite activity, such as watching a video, may serve as a suitable reward.

Infants

Administering medications to young infants can be relatively easy because of their small size. However, use of appropriate administration techniques is essential to prevent aspiration of liquid, oral medications or adverse effects from injections (see Chapter 6). Giving medications safely to a squirming, older infant can pose a great challenge, requiring the nurse to obtain help from other staff members to hold the child. Parents need to be informed about all medications their infant is receiving. Cuddling and comforting the infant before and after the procedure are also important interventions.

Toddlers and Preschoolers

Older toddlers (2 to 3 years of age) are prone to magical thinking and might view the administration of medication (especially if the procedure is invasive) as punishment for “bad” thoughts (see Chapter 7). The nurse prepares toddlers with age-appropriate explanations, using play if possible. Allowing older toddlers to examine the equipment before the procedure may enhance cooperation. Toddlers can prefer to sit on the parent’s lap when receiving medications. Helpful approaches for toddlers include praise and cuddling after procedures as well as giving rewards, such as stickers.

Preschoolers (3 to 5 years of age) continue to use magical thinking. They fear the unknown, and they fear painful procedures (see Chapter 7). This age-group benefits greatly from therapeutic play and participation. The nurse should offer the child as much control over the procedure and as many choices as possible (e.g., “Do you want to take your medication with juice or milk?”). The preschoolers may be able to hold still for an invasive procedure, although it is best to have a staff member ready to assist. Adhesive bandages after an invasive procedure, such as an injection, are important to children in this age-group because many believe a Band-Aid will “make it better’’; an example of magical thinking.

School-Age Children

School-age children fear loss of control, pain, and injury. At this age, a child can understand more complex explanations (see Chapter 8) as to why they need to take medication in order to recover from illness. Offering the child as much choice as possible is of great importance. School-age children often cooperate fully, even with invasive procedures, but often need a source of distraction (e.g., squeezing a person’s hand, listening to music, talking about a subject of interest) and support (see Chapters 37 and 39). School-age children still appreciate receiving praise and rewards.

Adolescents

Adolescents fear separation from peers and loss of control (see Chapter 9). Persons in this age-group understand adult explanations and can assist in making decisions about their nursing care. Often, however, adolescents exhibit a hyper-response to procedures that can seem inconsistent with their age. It is important to praise their cooperation, offer distractions, and help them find outlets for their frustrations (e.g., drawing, writing).

Calculating Dosages

The safe administration of medications to infants and children requires use of added safeguards that are above and beyond those for adult patients (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 2007). Incorrect dosing, which includes errors in dosage calculations and dosing intervals, is the most common type of medication error in pediatrics (AAP, 2007). The nurse must always verify the accuracy of the ordered dose of medication before administration. First, the recommended dosage for the medication in mg/kg/day is checked and a calculation performed based on the child’s weight to ensure that the right dose has been ordered. For example, the recommended dose for amoxicillin is 20 to 40 mg/kg/day; for a 10-kg child, the ordered dose should be between 200 and 400 mg per day. Second, the recommendation for the number of divided doses (e.g., every 4 hours, three times a day, every 12 hours) is confirmed. Last, the nurse ensures that route of administration is correct.

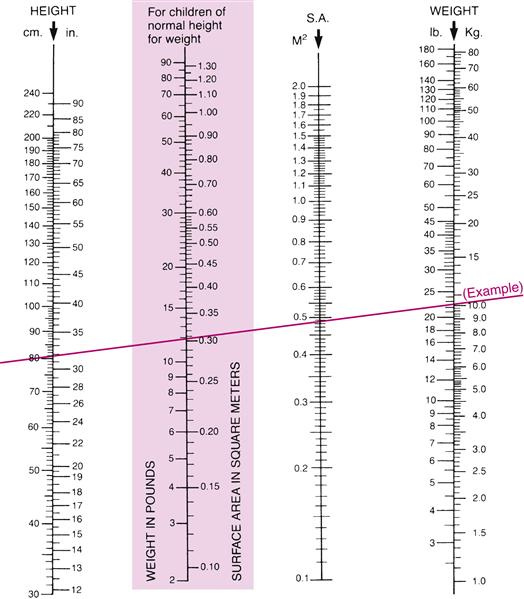

Dosages can also be calculated based on body surface area (BSA) (milligrams per square meter [mg/m2]). Figure 38-2 shows how to use a nomogram to obtain the BSA for a child. To calculate a medication dose on the basis of BSA, use the following formula:

Medication Administration Procedures

To avoid errors in medication administration, follow these general procedures:

• Check the orders to be sure that all information is correctly transcribed. Note any allergies.

• Ask another nurse to perform a second check for the following medications and any others as required by agency policy (Institute for Safe Medication Practices [ISMP], 2008):

• Insulin (subcutaneous and IV)

• Dextrose hypertonic IV solutions (20% or greater)

• Narcotics/opioids (transdermal, IV, and oral)

• Medications administered via epidural/intrathecal route

• Chemotherapeutic agents (oral and parenteral)

• Digoxin or other inotropic medications

• Anesthetic and moderate sedation agents (inhaled and IV)

• Potassium chloride, hypertonic sodium chloride, and magnesium sulfate for injection

Medication Reconciliation

When admitting children to a hospital unit, the nurse obtains a list of all prescription and over-the-counter medications as well as any herbal preparations a child is taking at home. To ensure patient safety, the nurse compares the medications the child has been receiving at home to the list of medications prescribed for the child’s hospital stay, identifying and communicating any discrepancies. This is referred to as medication reconciliation and is a process that is of paramount importance to preventing medication errors (Thompson, 2007). The Joint Commission’s national patient safety goals include an entire section on medication reconciliation listing detailed performance elements designed to ensure that accurate medication information is maintained and communicated among health care team members, patients, and their families (2011).

The nurse must also assess the parents’ knowledge of all the medications (and herbal remedies) the child is taking. This includes the name of the medication, the dose, number of times a day the child is taking the medication, knowledge of side effects, the child’s allergies, any adverse reactions the child might have experienced, and the time the medication was last administered. To facilitate medication reconciliation, parents are encouraged to bring all of their child’s medications to the hospital or a clinic visit. However, one study found that this occurs only about half of the time and that the majority of parents were not able to provide complete information about their child’s medication information, adversely affecting the medication reconciliation process (Riley-Lawless, 2009). At discharge, medication reconciliation includes providing clear, detailed written instructions to parents about all medications to be given at home as well as communicating precise medication information to the next health care provider.

Children are at greater risk than adults for medication errors and adverse drug events causing harm to a child because of pharmacokinetics, dosages by weight or body mass, and narrow therapeutic-to-lethal ranges for many medications (Takata, Taketomo, & Waite, 2008). The Joint Commission (2008) has indicated that a significant percentage of pediatric adverse drug events are preventable. Recommendations to reduce the risk of pediatric medication errors include the following:

• Establish and implement standardized medication procedures and processes for drug administration.

• Limit the number of concentrations and dose strengths of high alert medications.

• Use oral syringes to administer oral medications.

• Enable dose/dose range software programs to provide alerts for potentially incorrect dosages.

• Use bar-coding technology that is adapted to pediatric processes and systems.

• Use pediatric-specific medication formulations and concentrations.

• Comprehensive pediatric specialty training for all health care team members.

One of the major reasons for the increasing use of computer systems such as patient electronic medical records (EMRs) and computerized physician order entry (CPOE) is to reduce medication errors (Takata et al., 2008; Thompson, 2007). EMRs that include electronic medication administration records (EMARs) can improve communication of patient medication lists and other information, such as allergies, between different health care providers working in the same facility or in other settings (Agrawal & Wu, 2009). Use of web-based or computer dose calculators have been shown to reduce dosage calculation errors for pediatric patients (Conroy, Sweis, Planner, et al., 2007). Although electronic systems have shown great potential to significantly reduce the incidence of medication errors, they have limitations and cannot eliminate all errors (Gerstle & Lehmann, 2007). These systems do not replace the responsibility of physicians and nurses for clear and complete medication orders, accurate dose calculations, and correct administration of medications to children.

Administering Oral Medications

The oral route is the most widely used method of administering medications. It is also one of the least reliable methods of administration because absorption is affected by the presence or absence of food in the stomach, gastric emptying time, GI motility, and stomach acidity. The oral route can be less predictable also because of medication loss to spillage, leaking, or spitting out.

Oral medications are available in liquid (elixir or suspension), tablet or capsule, chewable tablet, or sprinkle (powder) forms. If the child cannot swallow tablets or capsules, the nurse finds out whether the medication is available in a liquid form or as a chewable tablet. If not, the nurse determines if the tablet can be crushed or if the contents of a capsule can be emptied. It is not recommended to crush time-release medications (e.g., extended-release [XR], controlled-release [CR], sustained-release [SR]), as well as enteric-coated tablets.

Before administering oral medications, the nurse assesses the child’s gag reflex and ability to swallow. The specific form of oral medication used should be tailored to the child’s developmental level and ability to successfully take a particular form. An assessment of the way the child takes medications at home will help determine the best form to use.

Preparation

When preparing to administer an elixir or a suspension, the nurse first ensures that the correct dose is drawn for administration. Physicians’ orders often specify the dosage in milligrams (mg), not milliliters (mL), for liquid medications. It is important to calculate the mL dose properly on the basis of the number of mg per mL for the available liquid medication.

For volumes of 5 mL or less, a calibrated spoon or dropper, or a syringe designed for oral medication administration only, should be used. Larger volumes are poured into calibrated plastic medicine cups, which generally hold up to 30 mL (1 oz).

The nurse can mix a sprinkle, powder, or crushed tablet with a small amount (e.g., 1 to 3 teaspoons) of a nonessential food such as applesauce or pudding or with a liquid. Mixing medications with necessary foods including formula is avoided because this can alter the food’s taste, and thus the child may refuse further intake of that food. The medication’s compatibility with food must be determined before mixing and administration.

Administration

The method for administering oral medications differs according to the child’s age and developmental level. Infants usually receive elixir or suspension forms that are administered using an empty nipple or oral syringe. First, the infant is placed in an upright or semi-upright position, similar to the position used for feeding. The nurse opens the infant’s mouth by applying gentle pressure to the chin or cheeks. If using a nipple, the nipple is placed in the infant’s mouth and the medication added to the empty nipple when the baby begins to suck. If using an oral syringe, the syringe is gently placed in the infant’s mouth along the side of the cheek, and the nurse pushes the medication in slowly as the infant sucks (Figure 38-3). It may be necessary to hold an infant or young child in order to safely administer an oral medication. As seen in Figure 38-3, the nurse cradles the child’s head between the nurse’s nondominant arm and body, holds the child’s hand with the nurse’s nondominant hand, and then administers the oral medication using the dominant hand.

Toddlers and preschoolers can easily take liquid medications from an oral syringe, a calibrated teaspoon, or a medicine cup. Allowing children to take their own medication, giving rewards as incentives, and providing choices that fit into the medication regimen enhance autonomy and cooperation.

Preschoolers and young school-age children can usually manage chewable tablets without difficulty. Many older, school-age children can swallow tablets or capsules; however, the nurse must assess a child’s ability to swallow pills on an individual basis. If a child cannot swallow pills, the availability of other forms of oral medications, such as liquid suspensions or elixirs and powders, needs to be investigated.

Oral medications are given with the child in an upright or slightly recumbent position to facilitate swallowing and prevent aspiration. After administration of the medication, the child is given a food or fluid item such as formula, juice, or an ice pop, if not contraindicated. Children are allowed to select what they would like to eat or drink after taking oral medications, whenever possible.

If a child vomits or spits up after administration of an oral medication, the nurse notifies the physician. Another dose may need to be ordered depending on how long it has been since administration, the type of medication, and the amount of emesis.

Alternative Routes for Oral Medications

Oral medications can be administered directly into the GI tract through a feeding tube. If the medication is to be administered through a feeding tube, verify tube placement before administration (see Chapter 37) and, depending on the type of tube (e.g., transpyloric), determine whether the tube is the proper route for the ordered medication. Before and after the medication is administered, the tube is flushed with water to ensure that the medication has reached the GI tract and to prevent blockage in the tube.

Administering Injections

Injected medications are rapidly absorbed by diffusing into either plasma or the lymphatic system. Although injections result in faster and more reliable absorption than the oral route, injections are stressful and threatening to children and are not preferred. Injections are used most often for one-time doses of antibiotics (e.g., ceftriaxone for the initial treatment of severe infection), immunizations, insulin administration for diabetics, purified protein derivative (PPD) tuberculosis skin test, and allergy skin testing.

Appropriately preparing the child for an injection can reduce emotional and anticipatory concerns. Depending on the child’s developmental level, explain the reason for the injection, any sensations the child might experience, and the length of time they are anticipated to last. Facilitate the child’s understanding that an injection is not punishment but is needed to help the child get well or stay healthy. Practice distraction techniques such as deep breathing and singing with the child in advance.

Offer parents the option to stay with their child during the procedure or leave if they feel unable to cope with the stress. Many parents prefer to remain and help distract, comfort, and reassure their child who is receiving an injection.

To reduce the risk of injury, it is sometimes necessary to limit the child’s movement before and during the administration of an injected medication. This can be accomplished by swaddling the child and/or obtaining the assistance of other health care professionals. Some parents may request to help hold their child while receiving an injection (Figure 38-4). Parents who feel confident in their ability to hold their child and prevent injury can be given this option. However, parents should not be required to restrain their child during a procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree