Indications for Intestinal Urinary Diversion

Benign Indications for Urinary Diversion

Incontinent Urinary Diversions

Cutaneous Catheterizable Urinary Diversion

Other Catheterizable Urinary Diversion

Intestinal urinary diversion is a general term used to describe the elimination of urine from the body through a surgically reconstructed intestinal segment. The name of the diversion type typically describes the particular intestinal segment utilized or the name of the institution at which it was developed (e.g., ileal conduit or Indiana pouch). The surgically reconstructed reservoir or channel allows for passage of urine through the urethra, a continent catheterizable channel on the skin, or an incontinent stoma on the skin. A wide variety of diversions have been developed to utilize bowel segments since the late 1800s, and the techniques have evolved with time.

Early urinary diversions involved bringing the ureters or bladder directly to the skin, which oftentimes resulted in stenosis at the skin level. Ureterosigmoidostomy whereby the ureters were anastomosed to the sigmoid colon and the anal sphincter provided continence, many times resulted in increased pyelonephritis and colon cancer, and has largely been abandoned as a diversion choice. In the 1950s, Bricker popularized and developed the ileal conduit in which urine drained from a budded stoma that was constructed on the patient’s abdomen. The ileal conduit resulted in improved patient quality of life and reduced stomal stenosis. More recently, continent diversions have improved the cosmesis of urinary diversion as patients eliminate their urine via small catheterizable channels on their abdomen or void via their native urethra (Pannek & Senge, 1998). Table 6-1 summarizes the most common incontinent and continent urinary diversions, which will be discussed further in this chapter.

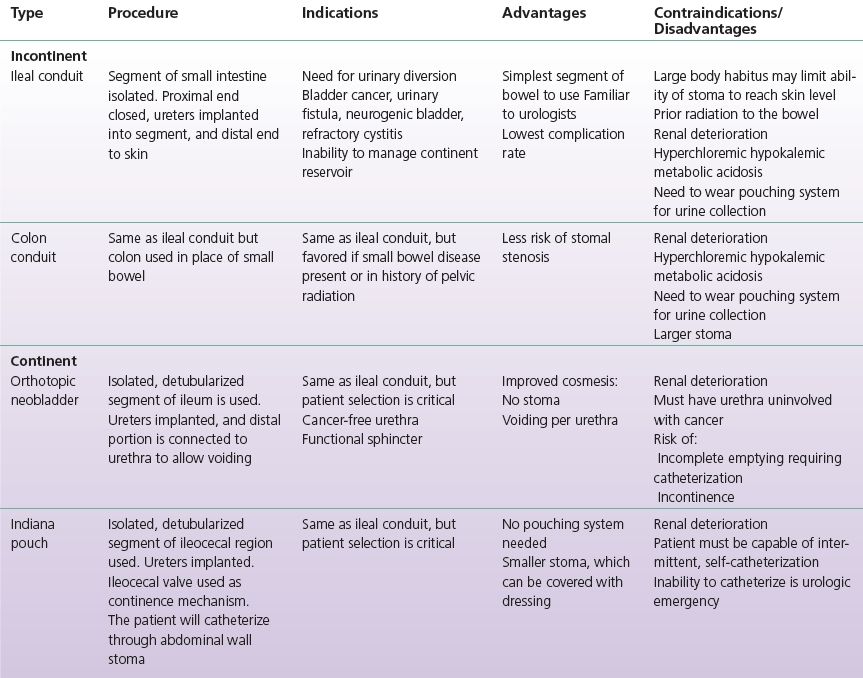

TABLE 6-1 Common Incontinent and Continent Urinary Diversion

Indications for Intestinal Urinary Diversion

There are both benign and malignant indications for intestinal urinary diversion. Urinary diversion is most commonly utilized when the bladder has to be removed due to malignancy. Less commonly, urinary diversion is utilized to divert urine from the bladder for benign indications due to severe bladder dysfunction, incontinence, bladder pain, or bleeding. In instances of benign urinary diversion, consideration must be taken to remove the bladder as some patients may develop pyocystis or infection in the native bladder. Pyocystis develops when the secretions of the native bladder accumulate and develop into an infection because there is no flow of urine through the bladder to eliminate these secretions. Pediatric conditions leading to a urinary diversion will be covered in Chapter 14.

Bladder Cancer

Bladder cancer is the fourth most common cause of cancer death in men in the United States with a 3:1 male-to-female ratio (Bladder Cancer Support Society, 2014). The average age at diagnosis is approximately 70 years. The most common histologic subtype of bladder cancer is urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Bladder cancer requiring removal of the bladder is the predominant indication for performing an intestinal urinary diversion.

Risk Factors

Several risk factors for bladder cancer have been implicated. The most common cause is cigarette smoking, which is a potent source for carcinogens that concentrate in the urine. Environmental exposure to chemicals (blue aniline dyes, chemicals in dye, paint, petroleum, rubber, and textile industries) has been implicated in the development of bladder cancer. Patients with chronic indwelling catheters or exposure to Bilharzia (parasite) have an increased risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder.

Presentation

More than 80% to 90% of cases of bladder cancer present with gross hematuria, which is typically painless and intermittent. Twenty to thirty percent of patients present with irritative voiding symptoms such as urgency/frequency and dysuria (pain with urination). Diagnosis of bladder cancer is often delayed, as patients are commonly misdiagnosed as having routine urinary tract infections, which oftentimes contributes to many patients presenting with advanced disease.

Histopathology

Bladder cancer arises from the inner lining of the bladder known as the mucosa. Bladder cancers have a spectrum of aggressiveness, which can be described by their grade (microscopic appearance of their cancer) and their invasiveness (depth of penetration into the bladder). The bladder has several layers from innermost to outmost: mucosa → submucosa → muscle → perivesical fat (fat surrounding the bladder). On one end, low-grade superficial tumors stay limited to the mucosal layer and have low risk of invasion to the deeper layer of the bladder. On the other end, higher-grade tumors can infiltrate the layers of the bladder typically in a stepwise manner resulting in patient morbidity and mortality (mucosa → submucosa → muscle → perivesical fat → lymph nodes → distant metastases).

Diagnostic Considerations

Patients who present with gross or microscopic hematuria typically undergo a standard urologic evaluation with imaging (contrast-enhanced CT scan of the kidneys, ureter, and bladder), urine cytology, and endoscopic evaluation of the urethra and bladder using a cystoscope. Once a bladder tumor is identified, patients are taken to the operating room where the bladder tumor is resected using a cystoscope that is placed through the patient’s urethra into the bladder. The resection allows for the microscopic determination of the histology (cell type), grade, and depth of penetration of the tumor into the bladder wall. Resection of the tumor is diagnostic, as well as prognostic, and therapeutic.

Management

Patients with lower-grade and noninvasive bladder tumors are good candidates for minimally invasive management, which includes administration of intravesical chemotherapy such as Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) and cystoscopic resection. After complete resection, these patients undergo close surveillance with frequent (every 3 to 6 months) cystoscopic evaluation of their bladder to identify recurrent tumors.

Patients with high-grade, recurrent, or invasive bladder cancer are recommended to undergo radical cystectomy if suitable operative candidates. In male patients, the bladder, prostate, and pelvic lymph nodes are removed; in female patients, the bladder, uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and anterior vagina are removed.

Alternative management strategies in patients who meet indications for radical cystectomy include administration of radiation and chemotherapy or partial resection of the bladder; however, these strategies are not a definitive or effective as is radical cystectomy.

Other Malignancies

Less common oncologic indications for removal of the bladder include gynecologic malignancy (vagina and uterus) and rectal malignancy, which locally invades the bladder necessitating cystectomy in appropriately selected patients.

Benign Indications for Urinary Diversion

Neurogenic Bladder

Neurogenic bladder is a generalized term describing bladder dysfunction caused by neurologic impairment of the central and peripheral nervous system, which innervates the bladder. Several conditions can result in neurogenic bladder and include stroke, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord trauma, diabetes, and postsurgical injury (radical hysterectomy, rectal surgery, spine surgery). These patients can have several bladder manifestations, namely, urinary incontinence, urinary retention, detrusor overactivity (irritable bladder), or high-pressure storage of urine. In a majority of cases, conservative medical and surgical management is adequate to treat neurogenic bladder; however, in severe cases, urinary diversion can be utilized as a last resort.

Radiation Cystitis

Patients who undergo radiation to their pelvis for treatment of malignancy (prostate, rectum, cervix/uterus) may develop incapacitating symptoms as a result of radiation-induced damage to the bladder and sphincter. This bladder damage can result in urinary incontinence, refractory bleeding, poorly compliant bladder, or painful bladder sensations with filling (Ratner, 2001). In cases refractory to medical management, urinary diversion is employed to divert the urine away from the bladder. These patients typically undergo ileal conduit diversions, since complication rates are higher in more complex continent diversions, especially in patients who have undergone radiation.

Interstitial Cystitis

Interstitial cystitis is a painful disorder of the bladder with unknown etiology. Patients typically present with pelvic/bladder pain with associated bladder symptoms (urgency, frequency, nocturia). These patients have negative findings in laboratory and urine studies and oftentimes have small ulcerations or petechial hemorrhage on cystoscopy. Only in refractory cases do these patients undergo urinary diversion and are good candidates for both incontinent and continent urinary diversions. After surgery, some patients continue to experience pelvic pain, and it is of paramount importance that these patients have appropriate preoperative counseling.

Trauma

Severe pelvic trauma resulting in partial or complete disruption of the urethra from the bladder may cause scarring and subsequent stricturing or the urethra. Patients with a severely strictured urethra who fail attempts to reconstruct the urethra typically drain their bladder with indwelling suprapubic catheters, which must be changed every 4 weeks to minimize infection and clogging. Some patients opt to have urinary diversion to avoid the use of an indwelling catheter.

Trauma involving the urinary sphincter can result in severe incontinence, which can be quite distressing to patients and negatively affect their quality of life. Furthermore, continuous leakage of urine results in perineal and sacral tissue breakdown and can negatively impair healing of sacral decubitus ulcers in patients with limited mobility and confined to their beds. Continent and incontinent urinary diversions are often performed depending on the patient’s preferences and physical limitations.

Surgical Procedures

Incontinent Urinary Diversions

Ileal Conduit

Incontinent urinary conduit in the form of an enterocutaneous stoma is a mainstay of urinary diversion. The ileum remains the most common segment of intestine used to create a conduit as it has the lowest complication rate and is most familiar to urologists. The ileal conduit may be the least cumbersome urinary diversion to manage from a patient perspective, as it only requires minor care of the stomal site and changing of the ostomy pouching system every 3 to 4 days. From a surgical perspective, the ileal conduit is the easiest to construct and requires shorter operative times.

Physician Considerations

Several factors are considered preoperatively when deciding what type of urinary diversion to construct for a patient. For patients with diseased intestine or multiple previous bowel resections, it is often preferred to maintain as much intestinal length as possible. Incontinent diversion requires shorter lengths of bowel (approximately 10 to 12 cm) compared to continent diversion (50 to 60 cm). Continent diversions are more technically challenging and may increase operative time, complication rate, and reoperation rate, compared to ileal conduits.

A history of prior pelvic radiation is a consideration when choosing the segment of bowel to use, as the ileum and sigmoid colon may have been included in the radiation field. A transverse colon conduit might be constructed in this circumstance.

Patient Considerations

Patient-specific factors are also important to consider. Undergoing urinary diversion can drastically alter body image. Patients who have ileal conduits must be willing to accept having a stoma on their abdomen and wearing pouching system to collect their urine. For continent cutaneous diversions, a minimal dressing is often placed over the small catheterizable stoma allowing patients to conceal their stoma. Patients with orthotopic urinary diversion or neobladders void via their urethra and do not have disfigurement of their abdomen with a stoma.

Patients who undergo continent diversion need to have sufficient general health, manual dexterity (i.e., ability to perform self-catheterization), motivation, and understanding to reliably manage their diversions. Patients who lack these qualities are better candidates for ileal conduit diversion, which is significantly easier to manage.

Regardless of continent or incontinent diversion choice, multiple studies have been performed without clear consensus of superior quality of life in patients with continent or incontinent urinary diversions (Gerharz et al., 2005).

Preoperative Considerations

Preoperative medical and cardiac clearance is performed to ensure that patient comorbidities are optimized before undergoing any intestinal urinary diversion. Specifically to urinary diversion, a preoperative consultation by the WOC nurse is critical for an optimal outcome. The visit is important for patient education, choice of preferred diversion type, and determination and marking of stoma site.

Some urologists choose to employ a mechanical and/or antibiotic preoperative bowel regimen. The goal is to decrease intestinal bacterial load in an effort to limit infectious complications. Mechanical preparations may include GoLytely, Fleet, Miralax, or magnesium citrate. All patients receive preoperative intravenous antibiotics immediately before surgery, which are usually stopped within 24 hours.

Surgical Procedure

The most distal 12- to 15-cm segment of ileum just proximal to the ileocecal valve is typically spared given its importance for bile salt and vitamin B12 absorption. A 10- to 12-cm segment of ileum proximal to this is identified. Transillumination of the mesentery is performed to ensure adequate blood supply to the segment. Surgical staplers are used to transect the bowel at each end of the conduit to isolate segment, and an anastomosis is performed to reestablish continuity of the bowel. It is important to maintain orientation of the conduit so that peristalsis is in the direction of urine flow.

Ureterointestinal anastomosis is performed in a refluxing manner near the proximal portion of the conduit over a stent, which aids in healing. There is some controversy over refluxing versus nonrefluxing anastomosis with some favoring nonrefluxing in an attempt to limit transmission of pressure and bacteria to the upper urinary tracts. While the nonrefluxing type is more technically challenging, it also has a higher stricture rate. There is no clear consensus as to an overall benefit of one method over the other (Kristjánsson et al., 1995).

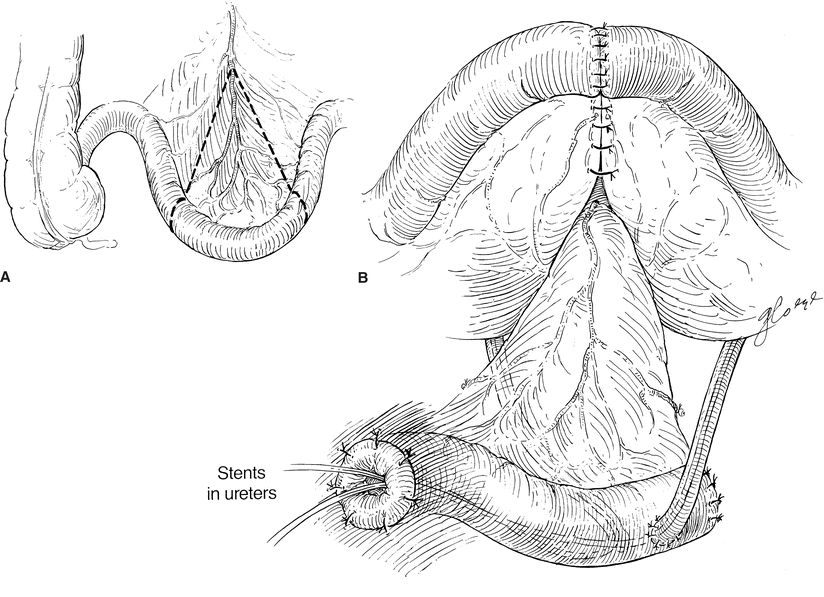

There are a variety of methods to manage the proximal end of the conduit. Some surgeons suture and/or excise the staple line in order to prevent urine from contacting the staples in an effort to prevent future stone formation. The distal portion of the conduit is delivered through the skin, and the staple line is excised. The stoma is matured with multiple sutures to form a rosebud appearance (Fig. 6-1). This elevated rosebud-shaped stoma limits the amount of urine that directly contacts the skin when an external stoma appliance is applied.

FIGURE 6-1. Ileal urinary conduit. A. A segment of nonirradiated ileum is used for the conduit. B. The ileum is reanastomosed, and the ureters are sewn into the “butt” end of the conduit. Note that ureters are stented individually.

Particularly in obese patients with a thick, short mesentery, a loop end ileostomy (Turnbull) can be performed. This allows creation of an ileal conduit with less tension, which may be required in these patients. If performed, a small rod is left in place temporarily through the mesentery at the skin level to prevent stomal retraction.

CLINICAL PEARL

A loop end (sometimes called an end loop) stoma will have a rod or support bridge under the bowel for support until healing takes place. The removal of the rod will depend upon the patient’s potential to heal and the amount of tension over the rod. The time the rod remains in place can vary from 5 days to 3 weeks after surgery.

Postoperative Care

The ureterointestinal anastomoses are performed over ureteral stents in order to maintain patency and allow proper healing. The distal aspect of a stent exits the stoma and can be a variety of colors or sizes. They may be sutured into place and empty directly into the pouching system. The stents are typically left in place anywhere from 5 days to 2 weeks after surgery depending upon the surgeon’s preference. Care must be taken with initial appliance changes not to dislodge the stents. Some surgeons choose to leave a catheter in the stoma to ensure adequate healing and drainage during the first initial days after surgery.

CLINICAL PEARL

Many surgeons will cut at least on stent on an angle to designate the right or left ureter. If the stents require shortening, a close examination of the stents should be performed prior to shortening (be sure to keep the cut on an angle).

Additionally, a closed suction, Jackson-Pratt or Blake drain is typically placed during surgery near the ureteroileal anastomosis and attached to bulb suction. This acts to diagnose and drain any urine leakage. This drain is typically removed before discharge as long as no significant leak is identified.

Some surgeons leave a nasogastric tube in place after surgery, which is removed at some point before initiating diet. Most practitioners await return of bowel function before starting any substantial oral intake. Early ambulation is critical in the prevention of deep vein thrombosis. A typical uncomplicated postoperative stay is between 5 and 10 days.

Early postoperative education is important for patients and their caregivers, who must learn to care for a new ostomy. Inpatient visits by the WOC nurse can avoid common pitfalls, which can minimize morbidity associated with incontinent urinary diversion.

Results

Ileal conduit urinary diversion is a complicated surgical procedure. Perioperative mortality ranges from 1% to 3% in large series in high-volume centers (Quek et al., 2006). Morbidity is significant, and complications include ileus, bowel leak, urine leak, infection, ureteral stricture, and stomal complications such as stenosis or hernia. Perioperative complication rate is reported in the range of 25% to 45% (Lowrance et al., 2008).

Complications

Stomal complications are common after incontinent urinary diversion. These include stomal stenosis, prolapse, retraction, and parastomal hernia. Stomal stenosis can sometimes be managed with catheterization but may necessitate revisional surgery. Retraction of the stoma may lead to difficulty in fitting of the appliance, which may result in skin irritation or urine leakage. Parastomal hernia is prevented by creating an appropriately sized fascial opening during surgery as well as placing the ostomy through the belly of the rectus abdominis muscle. An end loop stoma has a lower risk of stomal stenosis but a higher risk of parastomal hernia.

The ureterointestinal anastomoses may also be the source of complication, predominantly stricture or leak. Due to the more extensive mobilization of the left ureter, the left side is more commonly affected. Management of ureterointestinal stricture can be performed endoscopically with dilation/incision of the stricture with placement of ureteral stent; however, the most definitive and successful management strategy is open surgical revision. A fraction of these strictures may represent urothelial cancer as the ureteral margin may be a site of disease recurrence (Fichtner, 1999).

Infectious complications are common, especially in the initial period after urinary diversion. These may be in the form of abdominal abscess, urine leak, bowel leak, pyelonephritis, or wound infection. Treatment includes antibiotics and adequate drainage of any infectious collection. Patients with incontinent bowel diversion will commonly have chronic bacteriuria, and a majority of asymptomatic patients will have positive urine cultures. These patients are oftentimes treated inappropriately with repeated rounds of antibiotics resulting in multidrug-resistant organisms. Antibiotics should be reserved for patients with other clinical signs of infection.

The distal ileum is active in the absorption of vitamin B12 and bile salts. Vitamin B12 deficiency can potentially develop years after urinary diversion. Some practitioners routinely monitor and replace it as needed, often in the form of injection. If malabsorption of bile salts occurs, patients can experience a fatty diarrhea.

As bowel segments used for diversion are still metabolically active, resultant electrolyte and acid–base disturbances have been described for different bowel segments. For ileum, patients experience a hyperchloremic hypokalemic metabolic acidosis (Vasdev et al., 2013).

Over time, chronic renal insufficiency is not uncommon for patients with urinary diversions. This may be secondary to chronic obstruction, recurrent infections, or chronic exposure of the upper urinary tracts to bacteria.

Urolithiasis is another common complication. These may be in the form of calcium oxalate stones, the type most common in the general population, but chronic bacterial colonization can also cause magnesium ammonium phosphate stones to form. Stones may be located in the renal pelvis, in the ureter, or along the proximal ileal staple line if this was not excluded or excised during surgery. Retained foreign material from surgery such as stent fragments or permanent suture in contact with urine can act as a nidus for stone formation and should be avoided. These patients may be more complicated to treat with conventional methods given the altered anatomy of the urinary tract.

Colon Conduit

The use of colon for urinary diversion may be preferable in patients with prior pelvic radiation as portions may have been spared from the radiation field. The transverse colon is outside most radiation templates and is appropriate for use. A colon conduit urinary diversion may also be preferable in a patient with an existing colostomy for stool as it can obviate the need for bowel anastomosis and its associated morbidity.

Surgical Procedure

Sigmoid or transverse colon is most commonly used for creation of a colon urinary conduit. The steps are similar to creation of an ileal conduit. Directionality is maintained, and identification of adequate blood supply is critical. The segment of colon is taken out of continuity, and a bowel anastomosis is performed as previously described.

Postoperative Care

Immediate postoperative care is similar to an ileal conduit.

Complications

The stoma is slightly larger secondary to the caliber of colon, and therefore, stomal stenosis is less common. Otherwise, complications are similar. Patients with colonic urinary diversion also may experience a hyperchloremic hypokalemic metabolic acidosis.

Continent Urinary Diversions

Cutaneous Catheterizable Urinary Diversion

Cutaneous catheterizable urinary diversions involve the creation of an intestinal reservoir with an intestinal channel (catheterizable channel) that is brought from the reservoir to the skin. A variety of bowel segments can be used to create the reservoir (colon, ileum) as well as the catheterizable channel (colon, ileum, appendix). Generally, the continence between the reservoir and catheterizable channel is provided by either anatomic (i.e., ileocecal valve) or surgically constructed valves. The catheterizable channel must be catheterized several times during the day to empty the reservoir. It is imperative that any patient undergoing catheterizable continent urinary diversions has adequate mental capacity and hand–eye coordination to perform catheterizations multiple times per day.

Indiana Pouch

The Indiana pouch has become the predominant urinary diversion for patients who desire a continent catheterizable urinary diversion. Compared to orthotopic neobladders, patients do not need to have a patent urethra or a functional urinary sphincter. Indiana pouches can be performed in instances where the small intestinal segments are unable to reach the urethra in patients planned to undergo orthotopic neobladders; Indiana pouches are used as second-line continent urinary diversion in these instances (Rowland, 1996).

Contraindications for continent catheterizable channels include hepatic dysfunction, compromised intestinal function (i.e., previous surgery, radiation, inflammatory bowel disease), and renal failure (serum creatinine >1.7).

Physician Considerations

Indiana pouches are constructed from the terminal ileum, ileocecal valve, and right colon, and thus, these segments must be present (no prior resection, no significant disease burden, i.e., Crohn’s disease) in order to perform this diversion. Furthermore, the ileocecal valve must be functional as incompetence of this valve may result in leakage of urine from the valve (incontinence).

Patient Considerations

With any continent catheterizable diversion, patients must have both the mental capacity and motivation to maintain their urinary diversion, which requires frequent self-catheterizations and occasional irrigation of mucus from the reservoir of the Indiana pouch. Sufficient manual dexterity to perform self-catheterization is also critical. From a cosmetic standpoint, patients must accept the appearance of the catheterizable channel; however, the small stoma of the catheterizable channel can be easily concealed with a dressing (Lee et al., 2014).

Preoperative Considerations

Patients should undergo evaluation and stoma marking by the WOC nurse. This is an opportunity to determine the patient’s motivation, manual dexterity, and mental capacity. Selection of stoma site is determined on the right lower quadrant with consideration of belt line, skin folds, and ease of visualization by the patient.

Similar to patients undergoing ileal conduits, some urologists choose to employ a mechanical and/or antibiotic preoperative bowel regimen. All patients receive preoperative intravenous antibiotics immediately before surgery, which are usually stopped within 24 hours.

Surgical Procedure

The Indiana pouch is created from 10 to 12 cm of ileum (catheterizable channel), the ileocecal valve (continence mechanisms), and the right colon (reservoir). This segment of bowel is mobilized and discontinued from the remaining small and large bowel. Bowel continuity is reestablished by anastomosis of the ileum to the transverse colon using surgical staplers.

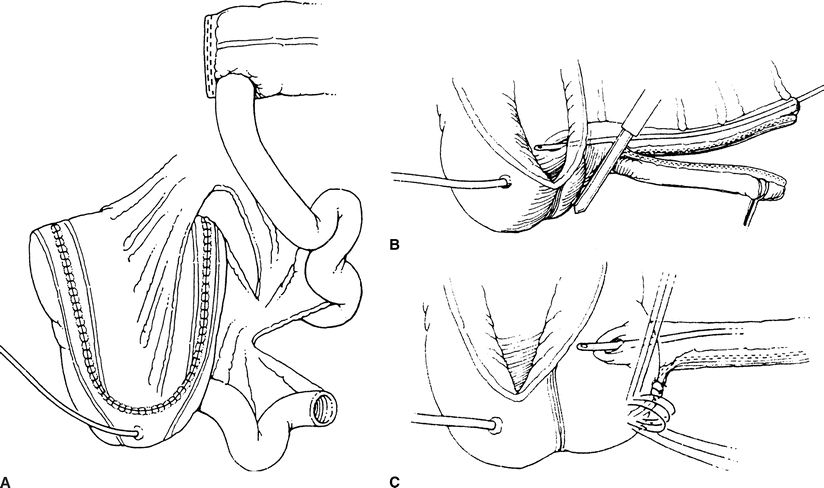

Next, the right colon is detubularized by incising it along its length to disrupt the muscular connections of the bowel (Fig. 6-2). Care is taken to avoid incising the ileocecal valve and terminal ileum. The ureters are passed through the posterior wall of the detubularized right colon and are secured to the inside of the pouch. These ureteral anastomoses are refluxing. Lastly, ureteral catheters or stents are placed into the ureters to protect the anastomoses and aid in their healing.

FIGURE 6-2. Indiana pouch. The entire right colon and 10 cm of distal ileum are isolated. The colon is incised along its antimesenteric border (making sure to preserve the ileocecal valve) and then folded upon itself in a Heineke-Mikulicz configuration. A. Prior to this step, however, the ureters are tunneled along the teniae in order to prevent reflux. The efferent ileal limb is tapered by imbrication over a 14-Fr catheter or, as performed by the authors, using a GIA stapler to remove excess ileum. B. The technique of ileocecal buttressing can be accomplished in several ways, including by taking purse-string sutures around the valve and apposing Lembert along the terminal ileum (C).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Surgical Procedures

Surgical Procedures Conclusions

Conclusions