Urinary Elimination

Objectives

• Describe the process of urination.

• Identify factors that commonly influence urinary elimination.

• Compare and contrast common alterations in urinary elimination.

• Obtain a nursing history for a patient with urinary elimination problems.

• Identify nursing diagnoses appropriate for patients with alterations in urinary elimination.

• Obtain urine specimens correctly.

• Describe characteristics of normal and abnormal urine.

• Describe the nursing implications of common diagnostic tests of the urinary system.

• Discuss nursing measures to promote normal micturition and reduce episodes of incontinence.

• Insert a urinary catheter correctly.

• Discuss nursing measures to reduce urinary tract infection.

• Irrigate a urinary catheter correctly.

Key Terms

Anuria, p. 1045

Bacteremia, p. 1046

Bacteriuria, p. 1046

Catheterization, p. 1061

Cystitis, p. 1047

Diuresis, p. 1045

Dysuria, p. 1047

Erythropoietin, p. 1043

Hematuria, p. 1047

Hyperactive/overactive bladder, p. 1047

Meatus, p. 1051

Micturition, p. 1044

Nephron, p. 1043

Nephrostomy, p. 1047

Nocturia, p. 1045

Nocturnal enuresis, p. 1049

Oliguria, p. 1045

Overflow incontinence, p. 1044

Pelvic floor exercises (Kegel exercises), p. 1066

Polyuria, p. 1045

Proteinuria, p. 1043

Pyelonephritis, p. 1047

Reflex incontinence, p. 1044

Renal calculus, p. 1044

Renal replacement therapy, p. 1045

Renin, p. 1043

Residual urine, p. 1046

Specific gravity, p. 1053

Stoma, p. 1046

Uremic syndrome, p. 1045

Urge incontinence, p. 1047

Urinalysis, p. 1053

Urinary diversion, p. 1046

Urinary frequency, p. 1049

Urinary incontinence, p. 1047

Urinary retention, p. 1046

Urosepsis, p. 1046

![]()

Normal elimination of urinary wastes is a basic function that most people take for granted. When the urinary system fails to function properly, eventually all organ systems are affected. Patients with alterations in urinary elimination often suffer emotionally from body image changes. It is important to know the reasons for urinary elimination problems, find acceptable solutions, and provide understanding and sensitivity to all patients’ needs.

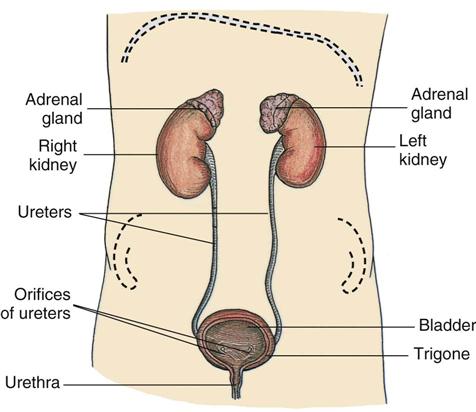

Scientific Knowledge Base

Urinary elimination depends on the function of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. Kidneys remove wastes from the blood to form urine. Ureters transport urine from the kidneys to the bladder. The bladder holds urine until the urge to urinate develops. Urine leaves the body through the urethra. All organs of the urinary system must be intact and functional for successful removal of urinary wastes. Intact efferent and afferent nerves from the bladder to the spinal cord and brain must be present (Fig. 45-1).

Kidneys

The kidneys lie on either side of the vertebral column behind the peritoneum and against the deep muscles of the back. Normally the left kidney is higher than the right because of the anatomical position of the liver.

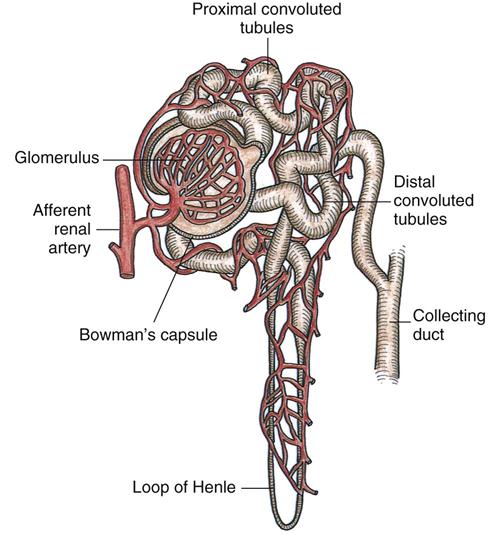

Kidneys filter waste products of metabolism that collect in the blood. The blood reaches each kidney by a renal (kidney) artery that branches from the abdominal aorta. Approximately 20% to 25% of the cardiac output circulates each minute through the kidneys. The nephron, the functional unit of the kidney, forms the urine. It is composed of the glomerulus, Bowman’s capsule, proximal convoluted tubule, loop of Henle, distal tubule, and collecting duct (Fig. 45-2).

A cluster of blood vessels forms the capillary network of the glomerulus, which is the initial site of filtration of the blood and the beginning of urine formation. The glomerular capillaries permit filtration of water, glucose, amino acids, urea, creatinine, and major electrolytes into Bowman’s capsule. Large proteins and blood cells do not normally filter through the glomerulus. The presence of large proteins in the urine (proteinuria) is a sign of glomerular injury. The glomerulus filters approximately 125 mL of filtrate per minute.

Not all of the glomerular filtrate is excreted as urine. Approximately 99% is resorbed into the plasma, with the remaining 1% excreted as urine (Huether et al., 2008). The kidneys play a key role in fluid and electrolyte balance (see Chapter 41). Although output does depend on intake, the normal adult urine output averages 1200 to 1500 mL/day. An output of less than 30 mL/hr indicates possible circulatory, blood volume, or renal alterations.

The kidneys produce several substances vital to red blood cell (RBC) production, blood pressure, and bone mineralization. They are responsible for maintaining a normal RBC volume by producing erythropoietin. Erythropoietin functions within the bone marrow to stimulate RBC production and maturation and prolongs the life of mature RBCs (Huether et al., 2008). Patients with chronic kidney conditions cannot produce sufficient quantities of this hormone; therefore they are prone to anemia.

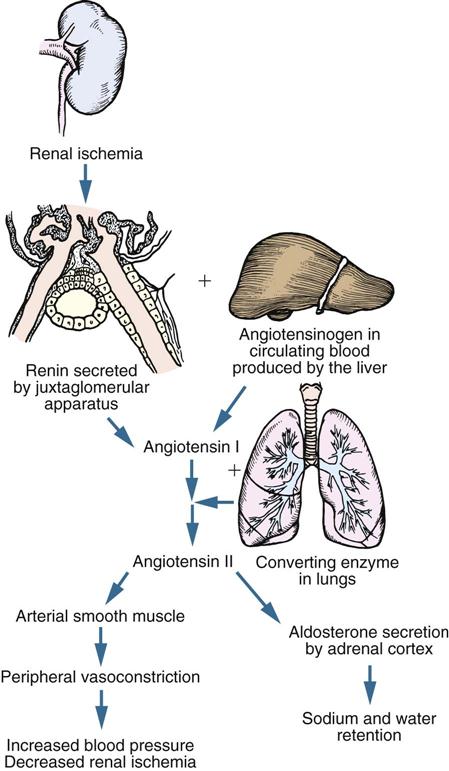

Renal hormones affect blood pressure regulation in several ways. In times of renal ischemia (decreased blood supply), renin is released from juxtaglomerular cells (Fig. 45-3). Renin functions as an enzyme to convert angiotensinogen (a substance synthesized by the liver) into angiotensin I. Angiotensin I is converted to angiotensin II in the lungs. Angiotensin II causes vasoconstriction and stimulates aldosterone release from the adrenal cortex. Aldosterone causes retention of water, which increases blood volume. The kidneys also produce prostaglandin E2 and prostacyclin, which help maintain renal blood flow through vasodilation. These mechanisms increase arterial blood pressure and renal blood flow (Huether et al., 2008).

The kidneys affect calcium and phosphate regulation by producing a substance that converts vitamin D into its active form. Patients with chronic alterations in kidney function do not make sufficient amounts of the active vitamin D. They are prone to develop renal bone disease resulting from the demineralization of bone caused by impaired calcium absorption.

Ureters

The ureters are tubular structures that enter the urinary bladder. Urine draining from the ureters to the bladder is usually sterile.

Peristaltic waves cause the urine to enter the bladder in spurts. The ureters enter obliquely through the posterior bladder wall. This arrangement prevents the reflux of urine from the bladder into the ureters during the act of micturition by the compression of the ureter at the ureterovesical junction (the juncture of the ureters with the bladder). An obstruction within a ureter such as a kidney stone (renal calculus) results in strong peristaltic waves that attempt to move the obstruction into the bladder. These waves result in pain often referred to as renal colic.

Bladder

The urinary bladder is a hollow, distensible, muscular organ (detrusor muscle) that stores and excretes urine. When empty, the bladder lies in the pelvic cavity behind the symphysis pubis. In men the bladder lies against the anterior wall of the rectum, and in women it rests against the anterior walls of the uterus and vagina.

The bladder expands as it becomes filled with urine. Pressure within it is usually low even when partly full, a factor that protects against infection. When the bladder is full, it expands and extends above the symphysis pubis. A greatly distended bladder may reach the level of the umbilicus. In a pregnant woman the developing fetus pushes against the bladder, reducing the capacity of the bladder and causing a feeling of fullness. This effect is more likely to occur in the first and third trimesters.

The trigone (a smooth triangular area on the inner surface of the bladder) is at the base of the bladder. An opening exists at each of the three angles of the trigone. Two are for the ureters, and one is for the urethra.

Urethra

Urine exits the bladder through the urethra and passes out of the body through the urethral meatus. Normally the turbulent flow of urine through the urethra washes it free of bacteria. Mucous membrane lines the urethra, and urethral glands secrete mucus into the urethral canal. Thick layers of smooth muscle surround the urethra. In addition, it descends through a layer of skeletal muscles called the pelvic floor muscles. When these muscles are contracted, it is possible to prevent urine flow through the urethra (Huether et al., 2008).

In women the urethra is approximately 4 to 6.5 cm ( to

to  inches) long. The external urethral sphincter, which is composed of skeletal muscle located about halfway down the urethra, permits voluntary flow of urine. However, the internal sphincter muscle is composed of smooth muscle and therefore is not under voluntary control. The short length of the urethra predisposes women and girls to infection. It is easy for bacteria to enter the urethra from the perineal area.

inches) long. The external urethral sphincter, which is composed of skeletal muscle located about halfway down the urethra, permits voluntary flow of urine. However, the internal sphincter muscle is composed of smooth muscle and therefore is not under voluntary control. The short length of the urethra predisposes women and girls to infection. It is easy for bacteria to enter the urethra from the perineal area.

In men the urethra, which is both a urinary canal and a passageway for cells and secretions from reproductive organs, is about 20 cm (8 inches) long. The male urethra has three sections: prostatic, membranous, and penile.

Act of Urination

Several brain structures influence bladder function, including the cerebral cortex, thalamus, hypothalamus, and brainstem. Together they inhibit the urge to void or allow voiding. Normal voiding involves contraction of the bladder and coordinated relaxation of the urethral sphincter and pelvic floor muscles.

Bladder capacity varies with the individual but generally ranges from 600 to 1000 mL of urine (Lewis et al., 2011), and an adult normally voids every 2 to 4 hours. However, individuals are able to sense the desire to urinate when the bladder contains a smaller amount of urine (150 to 200 mL in an adult and 50 to 100 mL in a child). It is important to teach parents that children do not have enough neurological development to be toilet trained until after 24 months and some are not developed enough until 36 months. As the volume increases, the bladder walls stretch, sending sensory impulses to the micturition center in the sacral spinal cord. Impulses from the micturition center respond to or ignore this urge, thus making urination under voluntary control. If the person chooses not to void, the external urinary sphincter remains contracted, inhibiting the micturition reflex. However, when a person is ready to void, the external sphincter relaxes, the micturition reflex stimulates the detrusor muscle to contract, and efficient emptying of the bladder occurs. It is vital that nurses understand this process to be able to assess and determine which form of incontinence or bladder problem may be occurring.

Damage to the spinal cord above the sacral region causes reflex incontinence. This condition causes loss of voluntary control of urination; but the micturition reflex pathway often remains intact, allowing urination to occur without sensation of the need to void. If a chronic obstruction caused by neurological damage such as prostate enlargement hinders bladder emptying, over time the micturition reflex changes, causing bladder overactivity and possibly causing the bladder to not empty completely. Overflow incontinence occurs when a bladder is overly full and bladder pressure exceeds sphincter pressure, resulting in involuntary leakage of urine. Causes often include head injury; spinal injury; multiple sclerosis; diabetes; trauma to the urinary system; and postanesthesia sedatives/hypnotics, tricyclics, and analgesia (Lewis et al., 2011). Hyperreflexia, a life-threatening problem affecting heart rate and blood pressure, is caused by an overly full bladder. It is usually neurogenic in nature; however, it can be caused functionally by blockage.

Factors Influencing Urination.

Many factors influence the volume and quality of urine and the patient’s ability to urinate. Some pathophysiological conditions are acute and reversible (urinary tract infection [UTI]), whereas others are chronic and irreversible (slow, progressive development of renal dysfunction). Sociocultural factors, psychological factors, fluid balance, and surgical and diagnostic procedures affect urine and urination in several ways. In addition, medications, including anesthesia, interfere with both the production and characteristics of urine, affect the act of urination, and affect the ability to completely empty or control voiding.

Disease Conditions.

Disease processes that affect urine elimination affect renal function (changes in urine volume or quality), the act of urine elimination, or both. Conditions that affect urine volume and quality are generally categorized as prerenal, renal, or postrenal in origin.

Decreased blood flow to and through the kidney (prerenal), disease conditions of the renal tissue (renal) and obstruction in the lower urinary tract that prevents urine flow from the kidneys (postrenal) sometimes alter renal function. Conditions of the lower urinary tract, including narrowing of the urethra, altered innervation of the bladder, or weakened pelvic and/or perineal muscles, affect urinary elimination.

Diabetes mellitus and neuromuscular diseases such as multiple sclerosis cause changes in nerve functions that can lead to possible loss of bladder tone, reduced sensation of bladder fullness, or inability to inhibit bladder contractions. Older men often suffer from benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), which makes them prone to urinary retention and incontinence. Some patients with cognitive impairments, such as Alzheimer’s disease, lose the ability to sense a full bladder or are unable to recall the procedure for voiding. Diseases that slow or hinder physical activity interfere with the ability to void. Degenerative joint disease and Parkinsonism are examples of conditions that make it difficult to reach and use toilet facilities.

Diseases that cause irreversible damage to kidney tissue result in end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Eventually the patient has symptoms resulting from uremic syndrome. An increase in nitrogenous wastes in the blood, marked fluid and electrolyte abnormalities, nausea, vomiting, headache, coma, and convulsions characterize this syndrome. As the uremic symptoms worsen, aggressive treatment is indicated for survival (Box 45-1). These treatments are renal replacement therapies.

Dialysis and organ transplantation are two methods of renal replacement. Dialysis takes one of two forms, peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis. Patients can use both dialysis modalities for a short or long term, but they require specialized equipment and nurses with specialized education.

Peritoneal dialysis is an indirect method of cleaning the blood of waste products using osmosis and diffusion, with the peritoneum functioning as a semipermeable membrane. This method removes excess fluid and waste products from the bloodstream when a sterile electrolyte solution (dialysate) is instilled into the peritoneal cavity by gravity via a surgically placed catheter. The dialysate remains in the cavity for a prescribed time interval and then is drained out by gravity, taking accumulated wastes and excess fluid and electrolytes with it.

Hemodialysis requires a machine equipped with a semipermeable filtering membrane (artificial kidney) that removes accumulated waste products and excess fluids from the blood. In the dialysis machine dialysate fluid is pumped through one side of the filter membrane (artificial kidney) while a patient’s blood passes through the other side. The processes of diffusion, osmosis, and ultrafiltration clean the patient’s blood. Then the blood returns through a specially placed vascular access device (Gore-Tex graft, arteriovenous fistula, or hemodialysis catheter).

Organ transplantation is the replacement of a patient’s diseased kidney with a healthy one from a living or cadaver donor of compatible blood and tissue type. The new organ is surgically implanted into the abdomen. Special medications (immunosuppressives) are administered, often for life, to prevent the body from rejecting the transplanted organ. Unlike the other treatments, successful organ transplantation offers patients the potential for restoration of normal kidney function.

Sociocultural Factors.

The degree of privacy needed for urination varies with cultural norms. North Americans expect toilet facilities to be private, whereas some European cultures accept communal toilet facilities. Social expectations (e.g., school recesses) influence the time of urination.

Psychological Factors.

Anxiety and emotional stress cause a sense of urgency and increased frequency of urination. Anxiety often prevents a person from being able to urinate completely; as a result, the urge to void returns shortly after voiding. Emotional tension makes it difficult to relax abdominal and perineal muscles. Attempting to void in a public restroom sometimes results in a temporary inability to void. Privacy and adequate time to urinate are usually important to most people.

Fluid Balance.

The kidneys primarily maintain the balance between retention and excretion of fluids (see Chapter 41). If fluids and the concentration of electrolytes and solutes are in equilibrium, an increase in fluid intake causes an increase in urine production. This amount varies with food and fluid intake. The volume of urine formed at night is about half of the volume formed during the day because both intake and metabolism decline. Nocturia (awakening to void one or more times at night) is often a sign of renal alteration. In a healthy person the intake of water in food and fluids balances the output of water in urine, feces, and insensible losses in perspiration and respiration. An excessive output of urine is polyuria. A urine output that is decreased despite normal intake is called oliguria. Oliguria often occurs when fluid loss through other means (e.g., perspiration, diarrhea, or vomiting) increases. It also occurs in early kidney disease. Often in severe kidney disease no urine is produced (anuria).

Ingestion of certain fluids directly affects urine production and excretion. Coffee, tea, cocoa, and cola drinks that contain caffeine promote increased urine formation (diuresis). Alcohol inhibits the release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH), also resulting in increased water loss in urine.

Febrile conditions affect urine production. A patient with excessive perspiration loses a large amount of fluids through insensible water loss, which decreases urine production. Fever causes an increase in body metabolism and accumulation of body wastes. Although urine volume is reduced, it is highly concentrated.

Surgical Procedures.

The stress of surgery initially triggers the general adaptation syndrome (see Chapter 37). Preoperative orders of nothing-by-mouth or an underlying disease condition affect fluid balance before surgery, which reduces urine output. In addition, the stress response releases an increased amount of ADH, which increases water resorption. Stress also elevates the level of aldosterone, causing retention of sodium and water. Both of these substances reduce urine output in an effort to maintain circulatory fluid volume.

Anesthetics and narcotic analgesics slow the glomerular filtration rate, reducing urine output. These pharmacological agents also impair sensory and motor impulses traveling among the bladder, spinal cord, and brain. Patients are often unable to sense bladder fullness and initiate or inhibit micturition. Spinal anesthetics, in particular, create the risk of urinary retention because of an inability to sense the need to void and a possible inability of the bladder muscles and urethral sphincters to respond (Lewis et al., 2011).

Surgery of lower abdominal and pelvic structures sometimes impairs urination because of local trauma to surrounding tissues. After returning from surgery involving the ureters, bladder, and urethra, patients routinely have urinary catheters.

Medications.

Many medications directly or indirectly contribute to urinary dysfunction. Antipsychotics, antidepressants, alpha-adrenergic agonists, and calcium channel blockers can cause urinary retention and overflow incontinence. Alpha-antagonists, diuretics, sedative hypnotics, opioid analgesics, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and antihistamines can cause urinary incontinence. Antiparkinson medications may cause urinary urgency and subsequent incontinence. Always consider these medications as the cause of new-onset urinary incontinence, especially in older adults.

Some medications change the color of urine. For example, phenazopyridine (Pyridium) colors the urine a bright orange to rust; amitriptyline causes a green or blue discoloration, whereas levodopa discolors the urine to brown or black. Cancer chemotherapy drugs also color the urine and are often toxic to the bladder and/or kidneys. Patients with impaired kidney function require dosage adjustments in medications excreted by the kidneys.

Diagnostic Examination.

Examination of the urinary system influences micturition. Some procedures such as an intravenous pyelogram (IVP) require patients to limit fluids before the test. A restriction in fluid intake commonly lowers urine output. Diagnostic examinations (e.g., cystoscopy) involving direct visualization of urinary structures cause localized edema of the urethral passageway and spasm of the bladder sphincter. After the procedure, a patient may have difficulty voiding or have red or pink urine because of trauma to the urethral or bladder mucosa.

Alterations in Urinary Elimination.

Most patients with urinary problems are unable to store urine or fully empty the bladder. These disturbances result from impaired bladder function, obstruction to urine outflow, or inability to voluntarily control micturition.

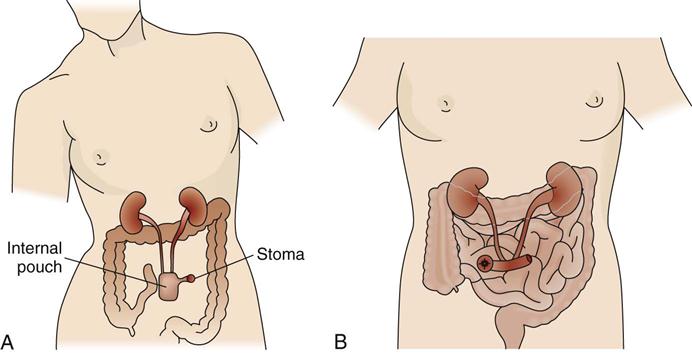

Some patients may have permanent or temporary changes in the normal pathway of urinary excretion. The surgical formation of a urinary diversion temporarily or permanently bypasses the bladder and urethra as the exit routes for urine. Permanent urinary diversions are often necessary in the patient with cancer of the bladder. The patient with a urinary diversion has a stoma (artificial opening) on the abdomen to drain urine. He or she has many special needs because urine drains to the outside through a stoma.

Urinary Retention.

Urinary retention is an accumulation of urine resulting from an inability of the bladder to empty properly. Normally urine production slowly fills the bladder and prevents activation of stretch receptors until it distends to a certain level of stretch. The micturition reflex occurs, and the bladder empties. In urinary retention the bladder is unable to respond to the micturition reflex and thus is unable to empty. Urine continues to collect in the bladder, stretching its walls and causing feelings of pressure, discomfort, tenderness over the symphysis pubis, restlessness, and diaphoresis (sweating).

As retention progresses, retention with overflow develops. Pressure in the bladder builds to a point at which the external urethral sphincter is unable to hold back urine. The sphincter temporarily opens to allow a small volume of urine (25 to 60 mL) to escape. As urine exits, the bladder pressure falls enough to allow the sphincter to regain control and close. With retention a patient may void small amounts of urine 2 or 3 times an hour with no real relief of discomfort or may continually dribble urine. Be aware of the volume and frequency of voiding to assess for urinary retention. Assess the abdomen for evidence of bladder distention and tenderness.

In acute retention key signs are bladder distention and absence of urine output over several hours. A patient under the influence of anesthetics or analgesics often feels only pressure, but the alert patient has severe pain as the bladder distends beyond its normal capacity. In severe urinary retention the bladder holds as much as 2000 to 3000 mL of urine. Retention occurs as a result of urethral obstruction, surgical or childbirth trauma, and alterations in motor and sensory innervation of the bladder such as occurs with neuropathy secondary to diabetes. It may occur after removal of an indwelling catheter. Medication side effects or anxiety may also result in urinary retention. If a patient cannot void or completely empty the bladder, he or she must be catheterized because a UTI, kidney stones, and hyperreflexia can occur.

Retained or residual urine, also referred to as postvoid residual (PVR), occurs if a patient has urinary retention or cannot empty the bladder completely. You can use a portable noninvasive bladder ultrasound device (bladder scanner) or the technique of straight/intermittent catheterization to assess for PVR. Bladder scanners are often not readily available for nurses to use in all clinical settings, and straight/intermittent catheterization may be the only means to determine bladder urine volume. Regardless of the method used to determine PVR, assess the amount of urine left in the bladder within 10 to 15 minutes after a patient voids (Altschuler and Diaz, 2006). Instruct the patient not to void again before measurement. At least two residuals should be obtained since a patient may empty well one time and not the next. Spastic bladders and some medications and problems such as using a bedpan or not sitting upright to void cause inconsistent emptying. In normal micturition or in a normal void the bladder should empty completely.

Urinary Tract Infections.

UTI is the most common health care–acquired infection; 80% of these infections result from the use of an indwelling urethral catheter (Lo et al., 2009). Catheterization results in over 1 million UTIs each year in the United States (Matteucci and Walsh, 2011). Infection frequently occurs after placement of urinary catheters, and each day a catheter is in place there is a 5% increase in bacteria in the urine (Saint et al., 2009). Catheter-associated UTIs (CAUTIs) are associated with increased hospitalizations, increased morbidity and mortality, longer hospital stay, and increased hospital costs (Newman, 2007). Each episode of CAUTI and ensuing complications are estimated to cost between $600 and $2800 (Saint et al., 2009). Because a CAUTI is common, costly, and believed to be reasonably preventable, as of October 1, 2008, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) chose it as one of the complications for which hospitals no longer receive additional payment to compensate for the extra cost of treatment (Saint et al., 2009). Consequently there has been a shift in reimbursement practices from its traditional focus on early recognition and prompt treatment to one of prevention (Wilson et al., 2009).

Although several different microorganisms cause CAUTIs, the patient’s own colonic flora, including Escherichia coli, remains the most common causative pathogen (Ksycki and Namias, 2009). Bacteriuria (bacteria in the urine) leads to the spread of organisms into the kidneys and possibly to bacteremia or urosepsis (bacteria in the bloodstream) (Lewis et al., 2011). Microorganisms commonly enter the urinary tract through the ascending urethral route. Bacteria inhabit the distal urethra and external genitalia in men and women and the vagina in women. Organisms enter the urethral meatus easily and travel up the inner mucosal lining to the bladder. Women are more susceptible to infection because of a short urethra and the proximity of the anus to the urethral meatus. In men prostatic secretions containing an antibacterial substance and the length of the urethra reduce the susceptibility to UTIs. However, men are at increased risk for infection-related renal disease. Older adults and patients with progressive underlying disease or decreased immunity are also at increased risk.

In a healthy person with good bladder function, organisms are flushed out during voiding. Residual (retained) urine in the bladder becomes more alkaline and is an ideal site for microorganism growth. Any condition resulting in urinary retention such as a kinked, obstructed, or clamped catheter increases the risk of a UTI.

Poor perineal hygiene is another cause of UTIs in women. Inadequate handwashing, failure to wipe from front to back after voiding or defecating, and frequent sexual intercourse predispose women to infection.

Patients with lower UTIs have pain or burning during urination (dysuria) as urine flows over inflamed tissues. Fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, and malaise develop as an infection worsens. An irritated bladder (cystitis) causes a frequent and urgent sensation of the need to void. Irritation to bladder and urethral mucosa results in blood-tinged urine (hematuria). The urine appears concentrated and cloudy because of the presence of white blood cells (WBCs) or bacteria. If infection spreads to the upper urinary tract (kidneys—pyelonephritis), flank pain, tenderness, fever, and chills are common.

Another common cause of infection is the introduction of instruments into the urinary tract. For example, the introduction of a catheter through the urethra provides a direct route for microorganisms (Nazarko, 2008). With an indwelling catheter bacteria ascend along the outside of the catheter on the urethral wall or travel up its lumen. Local irritation to the urethra or bladder predisposes tissues to bacterial invasion.

Urinary Incontinence.

Urinary incontinence is the involuntary leakage of urine that is sufficient to be a problem. It can be either temporary or permanent, continuous or intermittent. Urinary incontinence related to urinary causes is called either stress or urge urinary incontinence (Palmer and Newman, 2007). Urge incontinence is more common in younger women and may be caused by local irritating factors such as UTIs (Ebersole et al., 2008). Individuals sense the urge to urinate but cannot keep from urinating long enough to reach a toilet. Stress incontinence occurs more often in older women when intraabdominal pressure exceeds urethral resistance. Muscles around the urethra become weak; thus even a small amount of urine may leak spontaneously (Ebersole et al., 2008). Some patients may have a mixed form of incontinence that has features of both stress and urge urinary incontinence. Table 45-5 on p. 1060 describes the types of urinary incontinence, their symptoms, and treatment interventions. Hyperactive or overactive bladder (OAB) is associated with individuals of all ages, but older adults are more likely to have incontinence associated with it following physical and cognitive decline associated with aging and effects of medications (Stewart, 2010). OAB results from sudden, involuntary contraction of the muscles of the urinary bladder, resulting in an urge to urinate (urge incontinence). Common abnormalities of the nervous system that cause OAB include cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and other head injuries, spinal cord injury, and diabetic neuropathy. Other causes include UTI and anxiety.

Approximately 15% to 30% of adult women experience urinary incontinence. It is present in as many as 30% to 70% of nursing home residents and in 30% of adults living at home (Touhy and Jett, 2010). Incontinence can impair body image and often leads to a loss of independence. Clothing becomes wet with urine, and the accompanying odor adds to the embarrassment. As a result, patients with this problem often avoid social activities. They often fail to discuss this condition with health care providers or nurses, and as a result urinary incontinence is underreported and undertreated. Resources for information about continence care, patient education, and treatment are available at the following websites: the Society for Urological Nurses and Associates (http://www.suna.org), the National Association for Continence (http://www.nafc.org), and the Simon Foundation (http://www.simonfoundation.org).

Physical limitations and environmental barriers are risks for incontinence. People with restricted mobility have greater chances of being incontinent because of their inability to reach toilet facilities in time. Low-set chairs and beds raised well above the floor are obstacles for people who must get up to reach a toilet. Some patients often lack the energy to walk very far at one time. The toilet is sometimes too far away for patients with urge incontinence. Patients who have difficulty undoing buttons or manipulating zippers face another obstacle.

Continued episodes of incontinence is a risk for impaired skin integrity. The character of urine changes when it remains in contact with skin, causing skin breakdown. The immobilized patient with frequent incontinence is especially at risk for pressure ulcers (see Chapter 48). Additional health care and patient education resources are available at the websites for the American Geriatrics Society (http://www.americangeriatrics.org) or the American Urogynecologic Society (http://www.augs.org).

Urinary Diversions.

Conditions such as bladder cancer, radiation injury to the bladder, or chronic urinary infections may necessitate a urinary diversion to drain urine from a diseased or dysfunctional bladder. There are two types of continent urinary diversions (Fig. 45-4, A). One is a continent urinary reservoir that is created from a distal portion of the ileum and proximal portion of the colon. The ureters are embedded in the reservoir. This reservoir is situated under the abdominal wall and has a narrow ileal segment brought out through the abdominal wall to form a small stoma. The ileocecal valve creates a one-way valve in the pouch through which a catheter is inserted to empty the urine from the pouch. Patients must be willing and able to catheterize the pouch 4 to 6 times a day for the rest of their lives.

The second continent urinary diversion is an orthotopic neobladder that also uses an ileal pouch to replace the bladder. Anatomically the pouch is in the same position where the bladder was before removal, allowing patients to void normally.

Incontinent urinary diversions are less commonly performed. The surgery involves connecting the ureters to a section of the intestinal ileum with formation of a stoma on the abdominal wall (Fig. 45-4, B). Urine drains continuously because a patient has no sensation or control over urinary output, requiring the application of a collection pouch at all times.

Some patients need urinary drainage directly from one or both kidneys. In this case a tube is placed directly into the renal pelvis. This procedure is called a nephrostomy.

Any urinary diversion poses threats to a patient’s body image. The patient must learn how to manage the diversion, and those who do not have a continent urinary diversion must wear an artificial device at all times. However, most patients are able to wear normal clothing, engage in physical activity, travel, and have sexual relations. Care must be taken not to pull on tubing, especially in a nephrostomy, since it can be pulled out, causing tissue and organ damage and infection. Most nephrostomies are sutured into the kidney.

Refer patients with a urinary diversion to an ostomy nurse (a nurse with specialized education in this area). This specialist is a valuable resource for assisting a patient and family with matters pertaining to all aspects of care. The ostomy nurse often meets with the patient and family before surgery. In addition, refer the patient to the United Ostomy Associations of America (http://www.uoaa.org). This organization provides information about support groups to enhance coping and adaptation to lifestyle and body-image changes.

Nursing Knowledge Base

Urinary elimination is a basic function and is usually a private process. Many patients need physiological and psychological assistance from the nurse. Whether a patient has an actual or potential urinary problem, be sensitive to his or her elimination needs. You need knowledge of concepts beyond the anatomy and physiology of the urinary system to give appropriate care. In addition, you need to understand and apply knowledge about infection control principles.

Infection Control and Hygiene

The urinary tract is sterile. Use infection control principles to help prevent the development and spread of UTIs and treat existing infections. E. coli, a common bacteria found in feces, causes many CAUTIs. Infection can occur in any location of the urinary tract. Apply knowledge of medical and surgical asepsis when providing care involving the urinary tract or external genitalia (see Chapter 28). Any invasive procedure of the urinary tract such as catheterization requires sterile technique. Procedures such as perineal care or examination of the genitalia require medical asepsis, including proper hand hygiene. Use medical asepsis by wiping off tubing with antiseptic wipes when changing from a large-volume urinary bag to a small-volume leg bag.

Factors Influencing Urination

Factors in a patient’s history that normally affect urination are age, environmental factors, medication history, psychological factors, muscle tone, fluid balance, current surgical or diagnostic procedures, and presence of disease conditions. Be alert to individual needs related to normal changes of aging that predispose older adults to certain elimination problems (Box 45-2). Also assess the bowel elimination pattern because constipation often interferes with normal urine elimination (see Chapter 46). Problems with urination also stem from dehydration. Evaluate environmental barriers in the home or health care setting. Aids such as elevated toilet seats, grab bars, or a portable commode are often necessary to ensure patient safety.