Understanding Medicaid

Chapter objectives

After completion of this chapter, the student should be able to:

1. Explain Medicaid in general.

2. Summarize the evolution of Medicaid.

3. Describe the structure of Medicaid and identify federal and states’ roles.

4. List and briefly discuss key Medicaid programs (CHIP, EPSDT, PACE).

5. Identify Medicaid groups that are impacted by cost sharing.

6. Discuss circumstances that impact Medicaid payments to providers.

7. Explain the various methods for verifying Medicaid eligibility.

8. Describe the relationship between Medicare and Medicaid.

9. Discuss the role of managed care in Medicaid.

10. Outline the Medicaid claim process.

11. Interpret third-party liability as it relates to Medicaid.

12. List common Medicaid billing errors.

13. Demonstrate an understanding of the Medicaid standard remittance advice.

14. Define fraud and abuse and how it affects the Medicaid program.

Chapter terms

abuse

adjudicated

balance billing

budget period

capitation

categorically needy

Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

cost avoid(ance)

cost sharing (share of cost)

countable income

disproportionate share hospitals

dual coverage (Medi-Medi)

dual eligibles

Early Periodic Screening

Diagnosis and Treatment (EPSDT)

federal poverty level (FPL)

fraud

“in-kind” income

mandated services

Maternal and Child Health Services

Medi-Medi

Medicaid

Medicaid contractor

Medicaid integrity contractors

Medicaid secondary claim

Medicaid “simple” claim

medically necessary

medically needy

Medicare hospital insurance (Medicare HI)

Medicare-Medicaid crossover claims

optional services

payer of last resort

pay and chase claims

Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE)

Qualified Disabled and Working Individuals

Qualified Medicare Beneficiaries

reciprocity

remittance advice (RA)

safety-net providers

share of cost

Specified Low-Income Medicare Beneficiaries (SLMBs)

spend down

State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP)

supplemental medical insurance (SMI)

Supplemental Security Income (SSI)

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)

third-party liability

Evolution of medicaid

Medicaid originally was created to give low-income Americans access to healthcare. Since its beginning, Medicaid has evolved from a narrowly defined program available only to individuals eligible for cash assistance (welfare) into a large insurance program with complex eligibility rules. Today, Medicaid is a major social welfare program and is administered by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), formerly called the Healthcare Financing Administration (HCFA).

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

The Medicaid program, referred to in the past as Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), is now called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). TANF was created through a block grant by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996. The TANF block grant replaced the AFDC program, which had provided cash welfare to poor families with children since 1935. TANF is a federal-state cash assistance program for poor families typically headed by a single parent. Each state sets its own income eligibility guidelines for TANF, and individuals who are eligible for TANF automatically qualify for Medicaid.

Not all states refer to this program as TANF. Many states have coined their own names. Vermont calls it ANFC/RU (Aid to Needy Families with Children/Reach Up); New York calls it simply the Family Assistance (FA) Program; and Kentucky’s program is called K-TAP (Kentucky Transitional Assistance Program). To learn about the TANF program in your state, type the name of your state along with TANF in your Internet search engine.

Supplemental Security Income

In 1972 federal law established the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, which provides federally funded cash assistance to qualifying elderly and disabled poor. Under the SSI program, the Social Security Administration determines eligibility criteria and sets the cash benefit amounts for SSI. SSI is a cash benefit program controlled by the Social Security Administration; however, it is not related to the Social Security Program. States may choose to supplement federal SSI payments with state funds.

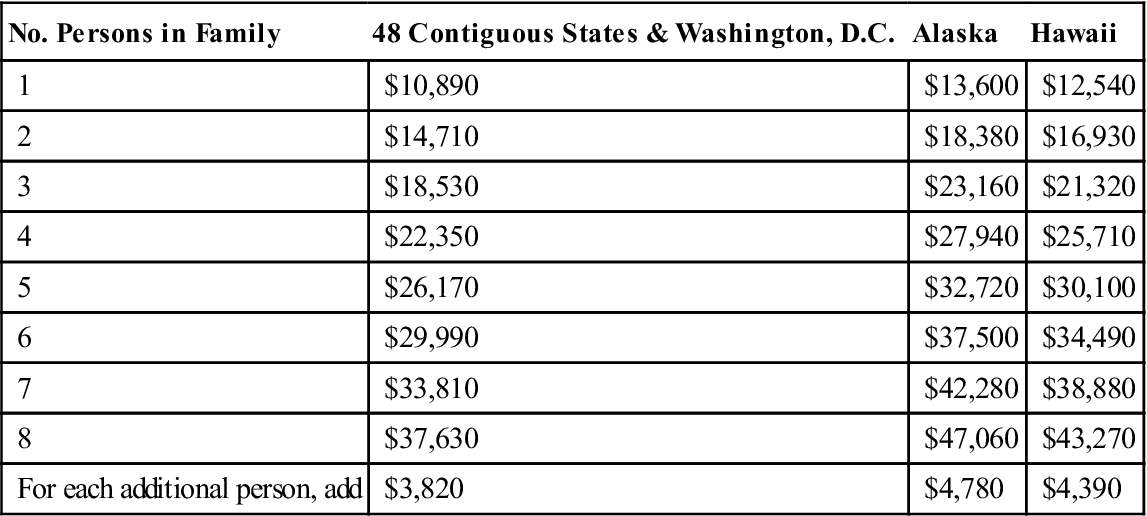

Eligibility

To be eligible for SSI, an individual must be at least 65 years old or blind or disabled and must have limited assets (or resources). Income is determined by the standards set forth in the federal poverty level (FPL) guidelines, shown in Table 8-1. The figures in this table represent the income of the individual or family. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issues new FPL guidelines in January or February each year. These guidelines serve as one of the indicators for determining eligibility in a wide variety of federal and state programs. The income benefits limit for SSI eligibility is $674 per month for an individual and $1011 for a couple (2011 figures). In most states, SSI beneficiaries also can get medical assistance (Medicaid) to pay for hospital stays, doctor bills, prescription drugs, and other health costs. In addition, to receive SSI, a person must:

• be a resident of the United States,

• not be absent from the country for more than 30 days, and

• be either a U.S. citizen or national, or in one of certain categories of eligible noncitizens.

Table 8-1

2011 Department of Health and Human Services Poverty Guidelines

| No. Persons in Family | 48 Contiguous States & Washington, D.C. | Alaska | Hawaii |

| 1 | $10,890 | $13,600 | $12,540 |

| 2 | $14,710 | $18,380 | $16,930 |

| 3 | $18,530 | $23,160 | $21,320 |

| 4 | $22,350 | $27,940 | $25,710 |

| 5 | $26,170 | $32,720 | $30,100 |

| 6 | $29,990 | $37,500 | $34,490 |

| 7 | $33,810 | $42,280 | $38,880 |

| 8 | $37,630 | $47,060 | $43,270 |

| For each additional person, add | $3,820 | $4,780 | $4,390 |

From Federal Register, Vol. 76, No. 13, January 20, 2011, pp 3637-3638.

(For SSI updates, see Websites to Explore at the end of this chapter).

(For SSI updates, see Websites to Explore at the end of this chapter).

The amount of the SSI payment is the difference between the individual’s countable income and the Federal Benefit Rate (FBR). Income is anything a person receives during a calendar month and uses to meet his or her needs for food, clothing, or shelter. It may be in cash income or “in-kind” income. In-kind income is not cash; it is food, clothing, shelter, or something one can use to obtain food (such as food stamps), clothing, or shelter. Countable income is the amount left over after

Many people who are eligible for SSI may also be entitled to receive Social Security benefits. In fact, the application for SSI is also an application for Social Security benefits. Unlike Social Security benefits, SSI benefits are not based on prior work or a family member’s prior work. It is easy to confuse SSI benefits with Social Security benefits. Refer to Box 8-1 for a comparison of the two programs.

Eligibility Expansion

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, Congress expanded Medicaid eligibility to include more categories of people—the poor elderly, individuals with disabilities, children, and certain categories of pregnant women. In addition to expansion of eligibility parameters, Medicaid programs were broadened as a result of federal mandates. These program expansions include the following:

• Payments to hospitals that serve large numbers of poor, uninsured, or Medicaid recipients

• Expansion of Medicaid to fill gaps in Medicare services to the poor elderly or disabled individuals

As a result of these and other federal law changes, the eligibility determination process is more complex today than in the past. Computer systems designed for a smaller and simpler program now manage information for millions of people in dozens of different eligibility groups.

Medicaid and Healthcare Reform

Unless the new healthcare reform laws are repealed, beginning in 2014, nearly everyone younger than 65 years with income up to 133% of the FPL will be eligible for Medicaid. Former categorical restrictions will be eliminated for those who fall into this group. These changes establish Medicaid as a way for low-income Americans to acquire near-universal coverage as approved in the healthcare reform law. Medicaid eligibility rules for the elderly and disabled will not change under health reform. For more information on how healthcare reform will affect the Medicaid program, type “Medicaid and Healthcare Reform” in your Internet search engine.

Structure of medicaid

As discussed in the beginning of this chapter, Medicaid is a combination federal and state public assistance program that pays for certain healthcare costs of individuals who qualify. The program is administered by CMS under the general direction of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Eligibility is based on need, which is determined by whether the patient meets certain income and resource limits. The federal government has established broad requirements for eligibility, and the individual states refine eligibility requirements and coverage to the needs of their populations.

Federal Government’s Role

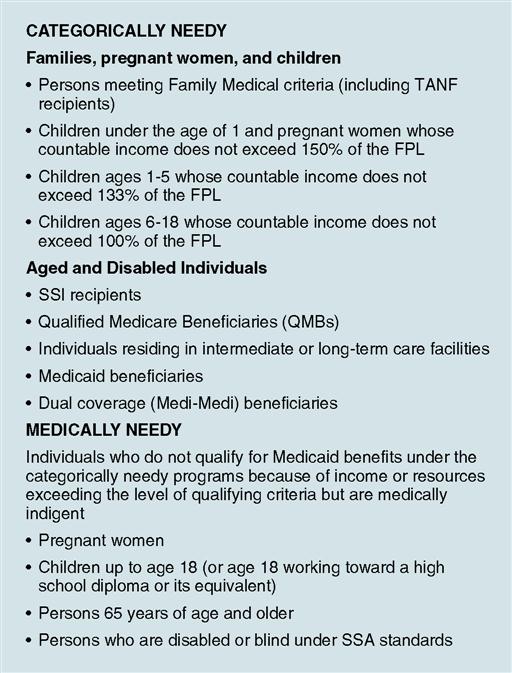

Within the guidelines set forth by the federal government, each state establishes its own eligibility standards; determines the type, amount, duration, and scope of services; sets the rate of payment for services; and administers its own program. Under the provisions of the federal statute, individuals, no matter what their financial status, must fall into a designated group before they are eligible for Medicaid. These groups are shown in Fig. 8-1.

Mandated Services

Title XIX of the Social Security Act requires that for a state to receive federal matching funds for their Medicaid programs, certain basic services (referred to as mandated [or mandatory] services) must be offered to the categorically needy population in the state’s program. These services are listed in Table 8-2. To see a timeline of Medicaid’s key developments, visit the Evolve site.

Table 8-2

Medicaid Mandatory and Optional Services

| Mandatory services | Inpatient hospital care |

| Outpatient hospital care | |

| Physician’s services | |

| Nurse midwife services | |

| Pediatric and family nurse practitioner services | |

| Federally qualified health center (“FQHC”) | |

| Laboratories and x-ray services | |

| Rural health clinic services | |

| Prenatal care | |

| Family planning services | |

| Skilled nursing facility services for persons over age 21 | |

| Home health care services for persons over age 21 who are eligible for skilled nursing services (includes medical supplies and equipment) | |

| Early periodic screening, diagnosis, and treatment (EPSDT) for persons under age 21 | |

| Vaccines for children | |

| States’ optional services* | Podiatrists’ services |

| Optometrists’ services and eyeglasses | |

| Chiropractic services | |

| Private duty nurses | |

| Clinic services | |

| Dental services | |

| Physical therapy | |

| Occupational therapy | |

| Speech, hearing, and language therapy | |

| Prescribed drugs | |

| Dentures | |

| Prosthetic devices | |

| Diagnostic services | |

| Screening services | |

| Preventive services | |

| Rehabilitative services | |

| Transportation services | |

| Services for persons age 65 or older in mental institutions | |

| Intermediate care facility services | |

| Intermediate care facility services for persons with MR/DD and related conditions | |

| Inpatient psychiatric services for persons under age 22 | |

| Christian Science schools | |

| Nursing facility services for persons under age 21 | |

| Emergency hospital services | |

| Personal care services | |

| Hospice care | |

| Case management services | |

| Respiratory care services | |

| Home- and community-based services for those with disabilities and chronic medical conditions |

*Note: Medicaid’s EPSDT program requires that states offer all these services to children up to age 21.

States’ Options

States may also receive federal funding if they elect to provide certain optional services in addition to the mandatory services that each Medicaid program must provide under federal statute. A state may choose from more than 30 optional services. Once an optional service is identified in the state plan, however, that service must be provided within federal requirements. The optional services authorized by the Medicaid Act include those listed in Table 8-2.

To be eligible for federal funds, states are required to provide Medicaid coverage for certain individuals who receive federally assisted income-maintenance payments and for related groups not receiving cash payments. In addition to their Medicaid programs, most states have other “state-only” programs to provide medical assistance for specified poor individuals who do not qualify for Medicaid. Federal funds are not provided for state-only programs.

Categorically Needy

States must cover categorically needy individuals, but they have options as to how to define categorically needy. Individuals falling into this group typically include those listed under the heading “Categorically Needy” in Fig. 8-1.Who qualifies for Medicaid benefits in a particular state varies according to the options that state has elected to include in the program. States that include the SSI program cover everyone who qualifies for the SSI (aged, blind, and disabled). These states cannot have rules, however, that are more restrictive than the federal government rules for SSI.

Medically Needy

More than 40 states plus the District of Columbia operate medically needy programs, which allow them to provide Medicaid to certain groups of individuals who are not otherwise eligible for Medicaid. People who have been denied Medicaid coverage because their income is too high might qualify as medically needy individuals on the basis of income and health status.

States that offer a medically needy program must cover pregnant women and children younger than 18 years. States also have the option to cover children up to age 21, parents and other caretaker relatives, elderly individuals, and individuals with disabilities. A state’s medically needy program may also expand coverage to people who spend down their income by accumulating medical expenses so that their income falls below a state-established medically needy income limit. A spend-down occurs when private or family finances are depleted to the point at which the individual or family becomes eligible for Medicaid assistance. Almost any medical bills that the applicant or the applicant’s family still owes or that were paid in the months for which Medicaid is requested (called the budget period) can be used to meet the spend down requirement. The opportunity to spend down may be particularly important to elderly residents in a nursing home. Also, children and adults with disabilities who may have high prescription drug, medical equipment, or other health care expenses may qualify for a spend down.

It is important to note, however, that Medicaid does not provide medical assistance for all poor persons. Even under the broadest provisions of the federal statute (except for emergency services for those who qualify), the Medicaid program does not provide healthcare services unless the individuals fall into one of the designated eligibility groups. Low income is only one test for Medicaid eligibility; assets and resources are also tested against established limits. As noted earlier, categorically needy persons who are eligible for Medicaid may or may not also receive cash assistance from the TANF program or from the SSI program. Medically needy persons who would be categorically eligible except for income or assets may become eligible for Medicaid solely as a result of excessive medical expenses.

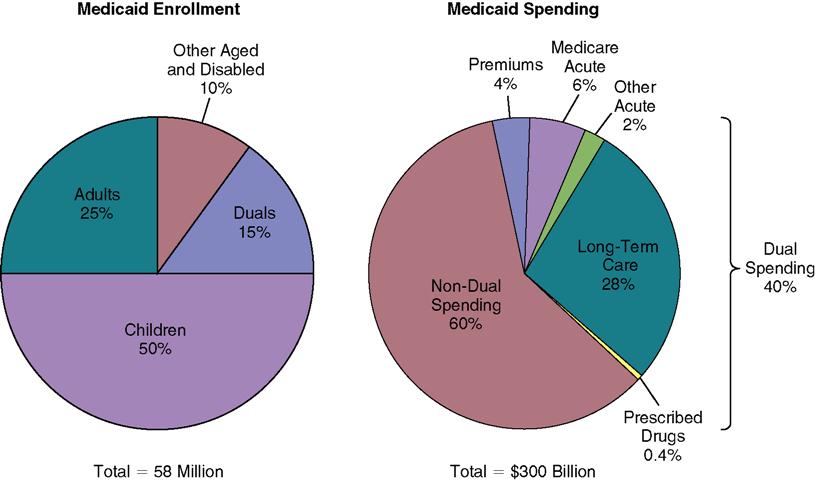

The Affordable Care Act, passed in March 2010, will significantly expand the number of people in the country who are eligible for Medicaid. This expansion may cover many of the people who currently are in a medically needy program. Fig. 8-2 shows pie charts illustrating Medicaid enrollment and Medicaid spending. To learn more about the Affordable Care Act, visit the Evolve site.

The health insurance professional must learn the specific guidelines for the Medicaid programs offered in the state in which he or she is employed in order to perform his or her job judiciously. The health insurance professional should contact the Medicaid contractor (a commercial insurer contracted by the HHS for the purpose of processing and administering claims) in his or her state to obtain a guide as to what programs are available and what each one covers in that state. An alternative resource for this information is listed in Websites to Explore at the end of this chapter. For a more in-depth discussion of Medicaid, visit the websites listed at the end of the chapter.

Community First Choice Option

The Community First Choice (CFC) Option is a relatively new state option that gives individuals with disabilities who are eligible for nursing homes and other institutional settings options to receive community-based services. CFC provides qualifying Medicaid beneficiaries the choice to leave facilities and institutions (e.g., nursing homes) for care in their own homes and communities with appropriate, cost-effective services and supports. CFC also helps address state waiting lists for services by providing qualified individuals access to a community-based benefit within Medicaid. The option does not allow caps on the number of individuals served, nor allow waiting lists for these services. For more information on Community First Choice Option, visit the Evolve site.

The Community First Choice (CFC) Option is a relatively new state option that gives individuals with disabilities who are eligible for nursing homes and other institutional settings options to receive community-based services. CFC provides qualifying Medicaid beneficiaries the choice to leave facilities and institutions (e.g., nursing homes) for care in their own homes and communities with appropriate, cost-effective services and supports. CFC also helps address state waiting lists for services by providing qualified individuals access to a community-based benefit within Medicaid. The option does not allow caps on the number of individuals served, nor allow waiting lists for these services. For more information on Community First Choice Option, visit the Evolve site.

State Children’s Health Insurance Program

Enacted as part of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP)—later known more simply as the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)—provides federal matching funds for states to implement health insurance programs for children in families that earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but too little to reasonably afford private health coverage. With CHIP, states can provide coverage through two different options:

States can operate either of these options, alone or in combination.

Within federal guidelines, each state determines the design of its CHIP program, eligibility groups, benefit packages, payment levels for coverage, and administrative and operating procedures. Eligibility levels range from 133% of the FPL in Wyoming to 350% of the FPL in New Jersey, with most states at 200% of FPL.

CHIP health benefits typically cover physician, hospital, well-baby, and well-child care; prescription drugs; and limited behavioral and personal care services. In contrast with Medicaid, private-duty nursing, personal care, and orthodontia are usually not covered by CHIP.

Many CHIP programs require small premiums and copayments, but federal law prohibits cost sharing from exceeding 5% of a family’s income. Most have a multilevel cost-sharing approach, with greater cost sharing for families with higher incomes (that is, above 150% of the FPL). Copayments range from $1 for a generic drug prescription to $100 for an inpatient hospital stay.

To learn more about the CHIP program, visit the Evolve site.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree