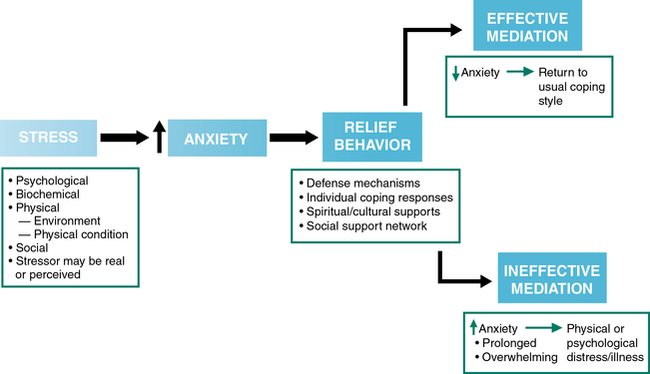

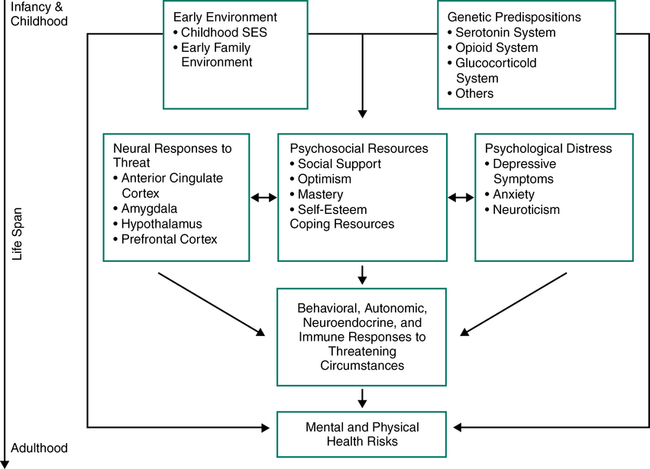

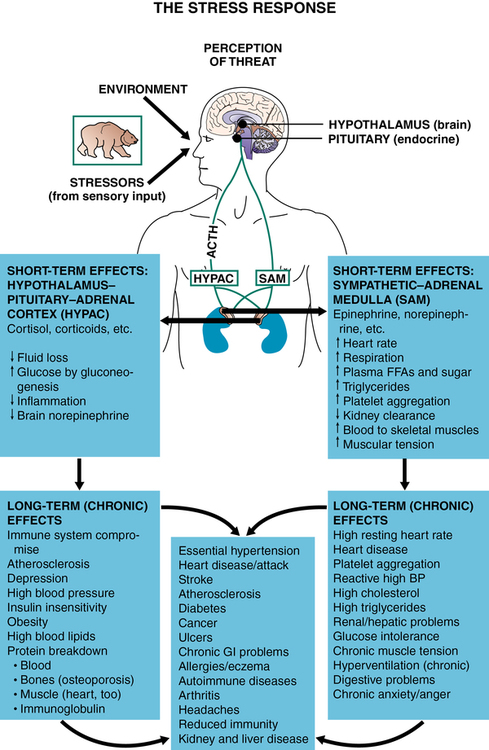

CHAPTER 10 Margaret Jordan Halter and Elizabeth M. Varcarolis 1. Recognize the short- and long-term physiological consequences of stress. 2. Compare and contrast Cannon’s (fight-or-flight), Selye’s (general adaptation syndrome), and psychoneuroimmunological models of stress. 3. Describe how responses to stress are mediated through perception, personality, social support, culture, and spirituality. 4. Assess stress level using the Recent Life Changes Questionnaire. 5. Identify and describe holistic approaches to stress management. 6. Teach a classmate or patient a behavioral technique to help lower stress and anxiety. 7. Explain how cognitive techniques can help increase a person’s tolerance for stressful events. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis Before turning our attention to the clinical disorders presented in the chapters that follow, we will explore the subject of stress. Stress is natural, and humans have evolved with a capacity to respond to internal and external situations. A classic definition of stress is that it is a negative emotional experience that results in predictable biochemical, physiological, cognitive, and behavioral changes directed at adjusting to the effects of the stress or altering the stress itself (Baum, 1990). Stress and our responses to it are central to psychiatric disorders and the provision of mental health care. The interplay among stress, the development of psychiatric disorders, and the exacerbation (worsening) of psychiatric symptoms has been widely researched. The old adage “what doesn’t kill you will make you stronger” does not hold true with the development of mental illness; early exposure to stressful events actually sensitizes people to stress in later life. In other words, we know that people who are exposed to high levels of stress as children—especially during stress-sensitive developmental periods—have a greater incidence of all mental illnesses as adults (Taylor, 2010). We do not know, however, if severe stress causes a vulnerability to mental illness or if vulnerability to mental illness influences the likelihood of adverse stress responses. It is most important to recognize that severe stress is unhealthy and can weaken biological resistance to psychiatric pathology in any individual; however, stress is especially harmful for those who have a genetic predisposition to these disorders. Figure 10-1 illustrates stress and health across the life span. It first takes into account nurture (environment) and nature (inborn qualities), responses to stressors (biological, social, and psychological), resultant physiological responses to stressors, and, finally, mental and physical health risks. The earliest research into the stress response (Figure 10-2) began as a result of observations that stressors brought about physical disorders or made existing conditions worse. Stressors are psychological or physical stimuli that are incompatible with current functioning and require adaptation. Walter Cannon (1871–1945) methodically investigated the sympathetic nervous system as a pathway of the response to stress, known more commonly as fight (aggression) or flight (withdrawal). The well-known fight-or-flight response is the body’s way of preparing for a situation an individual perceives as a threat to survival. This response results in increased blood pressure, heart rate, and cardiac output. While groundbreaking, Cannon’s theory has been criticized for being simplistic, since not all animals or people respond by fighting or fleeing. In the face of danger, some animals become still (think of a deer) to avoid being noticed or to observe the environment in a state of heightened awareness. Also, Cannon’s theory was developed primarily based on responses of animals and men. New research indicates that women may have unique physiological responses to stress. Physically, women have a lower hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and lower autonomic responses to stress at all ages, especially during pregnancy, and researchers hypothesize that estrogen exposure may regulate stress responses (Kajantie & Phillips, 2006). Men and women also have different neural responses to stress. While men experience altered prefrontal blood flow and increased salivary cortisol in response to stress, women experience increased limbic (emotional) activity and less significantly altered salivary cortisol (Wang et al., 2007). 1. The alarm (or acute stress) stage is the initial, brief, and adaptive response (fight or flight) to the stressor. During the alarm stage, there are three principle responses. • Sympathetic. The brain’s cortex and hypothalamus signal the adrenal glands to release the catecholamine adrenalin. This increases sympathetic system activity (e.g., increased heart rate, respirations, and blood pressure) to enhance strength and speed. Pupils dilate for a broad view of the environment, and blood is shunted away from the digestive tract (resulting in dry mouth) and kidneys to more essential organs. • Corticosteroids. The hypothalamus also sends messages to the adrenal cortex. The adrenal cortex produces corticosteroids to help increase muscle endurance and stamina whereas other nonessential functions (e.g., digestion) are decreased. Unfortunately, the corticosteroids also inhibit functions such as reproduction, growth, and immunity. • Endorphins. Endorphins are released to reduce sensitivity to pain and injury. These polypeptides interact with opioid receptors in the brain to limit the perception of pain. 2. The resistance stage could also be called the adaptation stage because it is during this time sustained and optimal resistance to the stressor occurs. Usually, stressors are successfully overcome; however, when they are not, the organism may experience the final exhaustion stage. 3. The exhaustion stage occurs when attempts to resist the stressor prove futile. At this point, resources are depleted, and the stress may become chronic, producing a wide array of psychological and physiological responses and even death. • Distress is a negative, draining energy that results in anxiety, depression, confusion, helplessness, hopelessness, and fatigue. Distress may be caused by such stressors as a death in the family, financial overload, or school/work demands. • Eustress (‘eu’ Greek for well, good + stress) is a positive, beneficial energy that motivates and results in feelings of happiness, hopefulness, and purposeful movement. Eustress is the result of a positive perception toward a stressor. Examples of eustress are a much-needed vacation, playing a favorite sport, the birth of a baby, or the challenge of a new job. Since the same physiological responses are in play with stress and eustress, eustress can still tax the system, and down-time is important. Furthermore, the GAS is most accurate in the description of how males respond when threatened. Females do not typically respond to stress by fighting or fleeing but rather by tending and befriending, a survival strategy that emphasizes the protection of the young and a reliance on the social network for support., Women are more vulnerable to stress-related disorders. This may be due to females being more sensitive to even low levels of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), a peptide hormone released from the hypothalamus in response to stress. Additionally, females seem to be less able to adapt to high levels of CRF as compared to men (Bangasser et al., 2010). Increased understanding of the exhaustion stage of the GAS has revealed that illness results from not only the depletion of reserves but also the stress mediators themselves. For example, people experiencing chronic distress have wounds that heal more slowly. Table 10-1 describes some reactions to acute and prolonged (chronic) stress. TABLE 10-1 SOME REACTIONS TO ACUTE AND PROLONGED (CHRONIC) STRESS Cannon and Selye focused on the physical and mental responses of the nervous and endocrine systems to acute and chronic stress. Later work revealed that there was also an interaction between the nervous system and the immune system that occurs during the alarm phase of the GAS. In one study, rats were given a mixture of saccharine along with a drug that reduces the immune system (Ader & Cohen, 1975). Afterward, when given only the saccharine, the rats continued to have decreased immune responses, which indicated that stress itself negatively impacts the body’s ability to produce a protective structure. The immune response and the resulting cytokine activity in the brain raise questions regarding their connection with psychological and cognitive states such as depression. Researchers have found concentrations of cytokines that cause systemic inflammation, especially tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin-6, to be significantly higher in depressed subjects compared with control subjects (Dowlati et al., 2010). Cancer patients are often treated with cytokine molecules known as interleukins; unfortunately, but understandably, these chemotherapy drugs tend to cause or increase depression (National Cancer Institute, 2011). Many dissimilar situations (e.g., emotional arousal, fatigue, fear, loss, humiliation, loss of blood, extreme happiness, unexpected success) are capable of producing stress and triggering the stress response (Selye, 1993). No individual factor can be singled out as the cause of the stress response; however, stressors can be divided into two categories: physical and psychological. Physical stressors include environmental conditions (e.g., trauma and excessive cold or heat) as well as physical conditions (e.g., infection, hemorrhage, hunger, and pain). Psychological stressors include such things as divorce, loss of a job, unmanageable debt, the death of a loved one, retirement, and fear of a terrorist attack as well as changes we might consider positive, such as marriage, the arrival of a new baby, or unexpected success. Have you ever noticed that something that upsets your friend doesn’t bother you at all? Or that your professor’s habit of going over the allotted class time drives you up a wall, yet (to your annoyance) your best friend in class doesn’t seem to notice? Researchers have looked at the degree to which various life events upset a specific individual and have, not surprisingly, found that the perception of a stressor determines the person’s emotional and psychological reactions to it (Rahe, 1995). Strong social support from significant others can enhance mental and physical health and act as a significant buffer against distress. A shared identity—whether with a family, social network, religious group, or colleagues—helps people overcome stressors more adaptively (Haslam & Reicher, 2006; Ysseldyk et al, 2010). Numerous studies have found a strong correlation between lower mortality rates and intact support systems; people, and even animals, without social companionship risk early death and have higher rates of illness (Taylor, 2010). The proliferation of self-help groups attests to the need for social supports, and the explosive growth of a great variety of support groups reflects their effectiveness for many people. Many of the support groups currently available are for people going through similar stressful life events: Alcoholics Anonymous (a prototype for 12-step programs), Gamblers Anonymous, Reach for Recovery (for cancer patients), and Parents Without Partners, to note but a few. The proliferation of online support groups provides cost-effective, anonymous, and easily accessible self-help for people with every disorder imaginable (McCormack, 2010). A Google search for online + support + groups yielded nearly 60 million hits; there has to be a group out there for everyone although quality and fit are always factors to be considered. Many spiritual and religious beliefs help persons cope with stress, and these deserve closer scientific investigation. Studies have demonstrated that spiritual practices can enhance the immune system and sense of well-being (Koenig et al., 2012). Some scholars propose that spiritual well-being helps people deal with health issues, primarily because spiritual beliefs help people cope with issues of living. Thus, people with spiritual beliefs have established coping mechanisms they employ in normal life and can use when faced with illness. People who include spiritual solutions to physical or mental distress often gain a sense of comfort and support that can aid in healing and lowering stress. Even prayer, in and of itself, can elicit the relaxation response (discussed later in this chapter) that is known to reduce stress physically and emotionally and to reduce stress on the immune system. Figure 10-3 operationally defines the process of stress and the positive or negative results of attempts to relieve stress, and Box 10-1 identifies several stress busters that can be incorporated into our lives with little effort. In 1967, Holmes and Rahe published the Social Readjustment Rating Scale. This life-change scale measures the level of positive or negative stressful life events over a 1-year period. The level, or life-change unit, of each event is assigned a score based on the degree of severity and/or disruption. This questionnaire has been rescaled twice, first in 1978 and again in 1997 when it was adapted as the Recent Life Changes Questionnaire. Since the scale was developed in 1967, life seems to have become more demanding and stressful. For example, travel is perceived as much more stressful now compared to 30 years ago. In 2007, online interviews were conducted to collect data from 1306 participants and then compared to data collected in the original study by Holmes and Rahe (First30Days, 2008). Although some life-change events were viewed as more stressful in 1967 (such as divorce and death of spouse), most events were viewed as more stressful in 2007 (Table 10-2). TABLE 10-2 PERCEPTION OF LIFE STRESSORS IN 1967 AND 2007 Data from First30Days. (2008). Making changes today considered more difficult to handle than 30 years ago. Retrieved from http://www.first30days.com/pages/press_changereport.html.

Understanding and managing responses to stress

Responses to and effects of stress

Early stress response theories

ACUTE STRESS CAN CAUSE

PROLONGED (CHRONIC) STRESS CAN CAUSE

Uneasiness and concern

Anxiety and panic attacks

Sadness

Depression or melancholia

Loss of appetite

Anorexia or overeating

Suppression of the immune system

Lowered resistance to infections, leading to increase in opportunistic viral and bacterial infections

Increased metabolism and use of body fats

Insulin-resistant diabetes

Hypertension

Infertility

Amenorrhea or loss of sex drive

Impotence, anovulation

Increased energy mobilization and use

Increased fatigue and irritability

Decreased memory and learning

Increased cardiovascular tone

Increased risk for cardiac events (e.g., heart attack, angina, and sudden heart-related death)

Increased risk of blood clots and stroke

Increased cardiopulmonary tone

Increased respiratory problems

Immune stress responses

Mediators of the stress response

Stressors

Perception

Social support

Support groups

Spirituality and religious beliefs

Nursing management of stress responses

Measuring stress

LIFE CHANGE EVENT

1967

2007

Death of spouse

100

80

Death of family member

63

70

Divorce/separation

73/65

66

Job lay off or firing

47

62

Birth of child/pregnancy

40

60

Death of friend

50

50

Marriage

50

50

Retirement

45

49

Marital reconciliation

45

48

Change job field

36

47

Child leaves home

29

43

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Understanding and managing responses to stress

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access