Chapter 57 Sexually transmitted infections

This chapter aims to enable the reader to:

Introduction

Most STIs are transmitted during sexual intercourse, non-penetrative genital contact, sex toys shared between partners or oral sex (BUPA 2007). Twenty-five types of STIs have been identified, although some – for example, vaginal candidiasis, pubic lice and scabies – can be acquired without sexual contact (Brook Advisory Centres 2008). Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, genital herpes simplex virus (HSV), genital human papillomavirus (HPV), non-specific infections, HIV, syphilis, HBV and trichomoniasis are the most common STIs.

Adverse trends in STIs in the UK are mainly attributable to rates of new HIV diagnoses and STIs in men who have sex with men. Although levels are relatively low, there has also been a steady increase in heterosexual HIV transmission, especially in the black ethnic minority. Most of the partners of infected black African and Caribbean people had probably been infected abroad (UK Collaborative Group for HIV and STI Surveillance 2007). Young adults (16–24 years of age) also appear to present a challenge as:

Controlling the transmission of HIV and STIs is a major public health challenge and midwifery practice involves responding to the challenge. Midwives are required to promote routine screening for HIV, HBV, and syphilis (DH 2003) to all pregnant women. Midwives encouraging sexual health and education during the booking visit may reduce transmission of infection, including mother-to-infant transmission, as well as facilitate early diagnosis and treatment of infected persons, which reduces associated morbidity and mortality. Midwives should ensure that women receive information about these screening tests, and advice about reducing the risk of STIs by reducing the number of partners and frequency of partner change, and using condoms correctly and consistently during sexual intercourse (HPA 2008a).

This chapter will examine the midwife’s role and underpinning ethical principles in relation to HIV screening, including the complex issues involved in decision making for the woman (Box 57.1). These principles, including accurate information based upon evidence, may also be applied to the midwife’s role when offering and recommending screening for HBV and syphilis. These STIs, in addition to other common STIs, will be discussed, with reference to clinical presentation, pregnancy implications and management. An understanding of the clinical presentation and management of STIs will enable midwives to effectively meet women’s sexual health needs.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

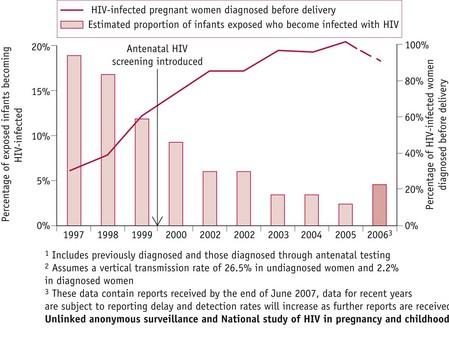

Unlinked anonymous surveillance of newborn infant dried blood spots shows that HIV prevalence in women giving birth varies widely nationally (Fig. 57.1) and is highest in urban areas, particularly London, where the prevalence has increased from 0.19% (200/106,407) in 1997 to 0.42% (502/119,614) in 2006 (UK Collaborative Group for HIV and STI Surveillance 2007). Women born abroad, especially in areas with generalized HIV epidemics, have a higher HIV prevalence than those born in the UK. One in every 2013 UK-born women giving birth in England was HIV-infected, compared with 1 in 138 non-UK-born women.

Figure 57.1 HIV prevalence among pregnant women by area of residence, England & Scotland (UK Collaborative Group for HIV and STI Surveillance 2007).

Disease progression

Sexual exposure is the primary method of spread of HIV infection worldwide. If left untreated, HIV damages the immune system, causing chronic and progressive illness as the infected person becomes vulnerable to a variety of infections (Bradley Hare 2006). Different stages of the disease have been identified (Pratt 2003):

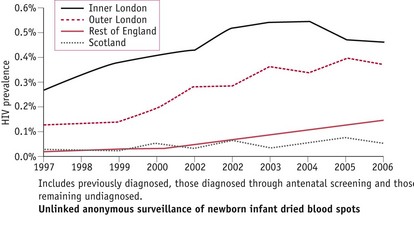

HIV screening during pregnancy

Since the implementation of routine screening during pregnancy, improved diagnostic rates for HIV have enabled infected women to make informed choices regarding interventions, reducing risks of mother-to-child-transmission (MTCT) of HIV infection from 25–30% to less than 2% (RCOG 2004). By 2006, more than 90% of pregnant women were aware of their HIV infection, resulting in a MTCT rate of less than 5% in the UK, compared with about 20% in 1997 (Fig. 57.2) (UK Collaborative Group for HIV and STI Surveillance 2007).

Beneficence

When applying ethical principles of beneficence (Ch. 8), the midwife should ensure outcomes of care result in ‘good’ being done to the woman and her baby. This entails informing women of the advantages of HIV testing during pregnancy, the benefits of which are listed below.

Preventing mother-to-child-transmission

Several well-conducted studies have shown that MTCT can be reduced by use of antiretroviral therapy, elective caesarean section (CS) and exclusively formula feeding the baby (Bott 2005). The HIV physician is responsible for determining treatment for individual women, taking into consideration maternal and fetal factors. For example, women with a low plasma viral load and a well-preserved CD4 T-lymphocyte count (website) can be treated either with single therapy (zidovudine) or with a combination of drugs referred to as HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy) following a consideration of the benefits (British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008, RCOG 2004) (Box 57.2). Women with advanced HIV (website) are likely to have symptomatic infection and falling CD4 T-lymphocyte counts and should be treated with a HAART regimen to improve maternal morbidity and mortality and prevent MTCT (RCOG 2004).

Box 57.2

Therapeutic options for women with a low plasma viral load and a well preserved CD4 T-lymphocyte count

| Option 1: Single-agent zidovudine regimen | Option 2: Short-term antiretroviral therapy regimen (START) |

• HAART may be discontinued shortly after delivery, provided that the maternal viral load is undetectable Benefits | |

| Benefits | |

• Zidovudine is usually administered orally to the neonate for 4–6 weeks, commencing as soon as possible after the birth | |

British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008, RCOG 2004

Further research to evaluate the effect on MTCT and maternal health of planned CS for women who are taking HAART or who have very low viral loads is indicated in British guidelines. However, delivery by CS is recommended for other women. Women choosing vaginal birth benefit from discussing a birth plan with their midwife, including guidelines for vaginal and CS births, to ensure maximum benefit and minimum harm (British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008, RCOG 2004) (Box 57.3).

Box 57.3

Guidelines for vaginal and CS births

| Elective CS | Planned vaginal delivery |

| • Clamp the cord as soon as possible after birth of baby | |

| • Test maternal blood at delivery for plasma viral load | |

| • Bath baby immediately after birth | |

British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008, RCOG 2004

Several studies have confirmed a 10–24% increase in MTCT of HIV when women breastfeed their babies (British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008). Transmission may occur throughout the period of breastfeeding, though the risk is influenced by breast milk virus load, which is highest early after delivery. Breastfeeding women have significantly higher median virus load in colostrum/early milk, compared with the mature breast milk collected 14 days after the birth of the baby (Rousseau et al 2003), and women with more advanced HIV are also more at risk of breast milk transmission (British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008). In the UK, midwives should advise all women who are HIV-positive to bottle-feed their babies to prevent MTCT (RCOG 2004). The Department of Health has issued guidance for healthcare professionals involved in supporting HIV-infected women to breastfeed their babies (see below).

To further reduce MTCT, HIV-infected women should be screened for other genital infections as early as possible in pregnancy and again at 28 weeks’ gestation (RCOG 2004).

Results from a comprehensive national surveillance study in England and Ireland conducted during 2002–2006 show that current options and treatment offered to pregnant women according to British guidelines appear to be effective in reducing MTCT. The overall MTCT was 1.2%, and it was 0.8% for women who received at least 14 days of antiretroviral therapy. Transmission rates were 0.7% for HAART with planned CS, 0.7% for HAART with planned vaginal delivery, and 0% for zidovudine monotherapy with planned CS (Townsend et al 2008). The transmissions that occurred despite woman taking HAART were mainly attributable to adherence problems and short duration of treatment.

Benefits for the mother

Early diagnosis of HIV improves maternal health and life expectancy as affected women benefit from being monitored and treated. The use of HAART has dramatically cut the number of deaths from AIDS-related illnesses and women benefit from PCP prophylaxis with co-trimoxazole, which is usually administered when the CD4 T-lymphocyte count is below 200 × 106/L. With appropriate treatment, affected people now have a near-normal life expectancy (BUPA 2008, RCOG 2004).

Benefits for the baby

Babies benefit from being followed up, and receiving appropriate treatment as necessary. Virologic testing of babies to diagnose HIV infection is recommended at 1 day, 6 weeks and 12 weeks of age (British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008). If the test results show a baby is HIV-infected, urgent referral to a specialist clinic enables early commencement of combination antiretroviral therapy. If the test results are negative, parents can be reassured that their baby is not infected with HIV, providing breastfeeding has been avoided. PCP prophylaxis is recommended for babies born to mothers at high risk of MTCT (British HIV Association & Children’s HIV Association 2008). A negative HIV antibody test result at 18 months of age will confirm that the child is uninfected (RCOG 2004).

Mortality, AIDS, and hospital admission rates have declined substantially in perinatally HIV-infected children in the UK and Ireland, paralleling the increased use of combination antiretroviral therapy. Mortality decreased by 80% between 1997 and 2001–02, AIDS progression decreased by 50% and hospital admission rates decreased by 80% (Gibb et al 2003).

Non-maleficence

When applying the ethical principle of non-maleficence, the midwife should ensure that any act or omission does not result in harm. Being aware of the potential ‘harm’ (Box 57.4) facilitates discussion of individual concerns with women, who themselves must decide whether screening is in their best interests. Knowledge regarding potential effects of different treatments and interventions assists provision of optimum care.