Chapter 32 Confirming pregnancy and care of the pregnant woman

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

Introduction

This chapter focuses upon the care and services provided and delivered to women during the antenatal period from the point at which a woman believes she may be pregnant to the onset of labour. During this period, pregnant women experience major physiological and psychological changes facilitating adaptation and preparation for birthing and transition to parenting (Coad & Dunstall 2005, Stables & Rankin 2005). Midwives are key professionals who deliver care to the women and their families. They work in partnership with women to assess women’s individual needs and to plan and implement the most appropriate care.

Confirmation of pregnancy

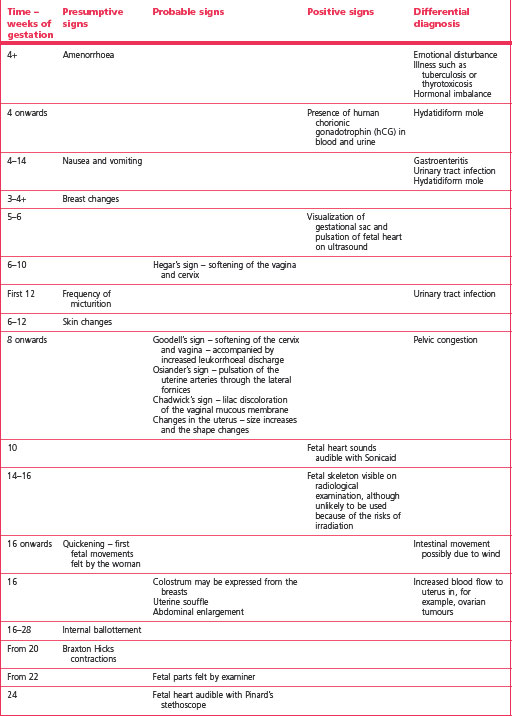

Signs and symptoms of pregnancy may be considered as presumptive, probable and positive, as illustrated in Table 32.1.

First 4 weeks

Nausea and vomiting

These are common symptoms, with nausea affecting about 70% to 85% of pregnant women and vomiting approximately 50% (Gadsby et al 1993, Lacroix et al 2000, Whitehead et al 1992). Of the women who experience nausea, only a small percentage experience it in the morning but many suffer from it throughout the day. Vomiting, however, is also a feature of a variety of conditions, such as gastroenteritis, urinary tract infection and hydatidiform mole, and these should be ruled out.

Around 12 weeks

Around 16 weeks

Quickening

The first fetal movements may be felt by primigravidae at 19+ weeks and by multigravidae at 17+ weeks. The time scale over which fetal movements are first felt by the mother ranges from 15 to 22 weeks in primigravidae and from 14 to 22 weeks in multigravidae (O’Dowd & O’Dowd 1985). Quickening, often described as ‘flutters’, or a feeling of ‘bubbles coming to the surface’ rather than recognizable movements, is an unreliable indicator of gestational age as sometimes these feelings can be attributed to flatulence.

Around 20 weeks

For 90% of women, nausea and vomiting have usually diminished by 22 weeks’ gestation (Lacroix et al 2000). The secondary areola, if not already present, may appear. The fundus of the uterus is normally palpated just below the umbilicus.

Signs of pregnancy found by vaginal examination

Positive signs of pregnancy

Laboratory diagnosis of pregnancy

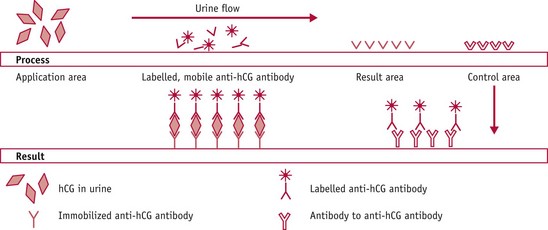

Figure 32.2 The principle of the wick test as used in dipstick and cassette devices.

(From Wheeler 1999.)

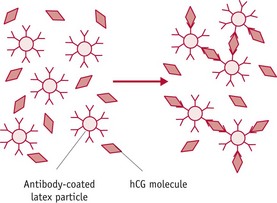

Up to 40 types of laboratory test kit are available in the UK (Wheeler 1999). These have a wide range of different sensitivities, from 20 to 1000 IU/L of hCG.

Home pregnancy tests have a more consistent range of sensitivity, from 25 to 50 IU/L, take from 1 minute to obtain a result, appear easy to use and manufacturers claim a 99% accuracy rate. However, an American meta-analysis of the efficiency, sensitivity and specificity of tests highlighted that the diagnostic efficiency of home pregnancy tests is affected by the characteristics of the users (Bastian et al 1998). False negative results arose from testing before the recommended number of days from the last menstrual period, or from a failure to read or follow the instructions. Therefore, a negative result in a woman who does not menstruate within a week should be treated with caution. The test should be repeated and laboratory confirmation sought if doubt of pregnancy exists.

Antenatal care

Over the past two centuries, antenatal services have seen major developments in terms of their provision and delivery. Contemporary antenatal services have quality at their heart, with patient safety, patient experience and effectiveness of care as their central tenets (DH 2008). All women seek a healthy outcome to their pregnancy; they want high-quality, personalized care coupled with greater information so that they can make informed choice about the place and nature of their care and are more in control of the care that they receive (Redshaw et al 2007).

The UK maternity services aim to provide a world-class service to women and their families, with the overall vision for the services to be flexible and individualized. Services should be designed to fit around the needs of the woman, baby and family circumstances, with due consideration being given to factors that may render some women and their families to become vulnerable and disadvantaged. Pregnancy is a normal physiological process for the majority of women. Women and their families need support to have as normal a pregnancy and birth as possible, with medical intervention being offered only if it is of benefit. However, in some circumstances, both midwifery and obstetric care are indicated and care should be based on providing good clinical and psychological outcomes for the woman and her baby (DH 2007a, DH & DfES 2004, NICE 2008).

Aims of antenatal care

Care during pregnancy

It is important that women seek professional healthcare early in pregnancy – that is, within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy (HM Treasury 2007, Lewis 2007, NICE 2008) – so that they can obtain and use evidence-based information to plan their pregnancy and to benefit from antenatal screening and health promotion activities (DH 2007a, DH & DfES 2004, NICE 2008). With early information about the available models of antenatal care, women, in partnership with healthcare professionals, can make decisions about the most appropriate pathway of their care best suited to their personal, social and obstetric circumstances.

Where women seek care at a later stage in pregnancy, they will have reduced access to antenatal care. It is likely that the woman will have reduced options in terms of antenatal screening tests. Some investigations, such as serum screening for Down syndrome (see Ch. 26), are accurate only if carried out at specific times, in this case between 15 and 18 weeks. Early detection of these conditions enables further investigations, such as ultrasound scan or amniocentesis, to be carried out at the optimum time.

The woman should be able to choose whether her first contact in pregnancy is with a midwife or her GP (DH 2007a). That said, antenatal services vary; in many parts of the UK, the first point of contact for maternity services is the woman’s GP (CHAI 2008, Redshaw et al 2007), but services are working towards the midwife being the first point of contact in the community setting.

To achieve the principles of antenatal care, pregnant women require evidence-based information. Evidence suggests that women desire accurate and timely information about pregnancy and childbirth so that they can develop their knowledge and understanding of pregnancy, childbirth and related issues, enabling them to make informed decisions about the care they want and prefer (Bharj 2007, Kirkham & Stapleton 2001, Mander 2001, Singh & Newburn 2000). Women need information which is based upon current evidence that is clearly understood and in a format they can easily access. When offering information, healthcare professionals must take into account the requirements of women who have physical and sensory learning disabilities and women whose competence in speaking and reading English is low, exploring appropriate ways of exchanging meaningful information.

Midwives are key healthcare professionals who work with women to support them to make informed choices regarding preferred arrangements for antenatal care, place of birth and postnatal care. Midwives should be friendly, kind, caring, approachable, non-judgemental, have time for women, be respectful, good communicators, providing support and companionship (Bharj & Chesney 2009, Nicholls & Webb 2006). These attributes are essential for the development of the woman–midwife relationship. Many worldwide studies highlight that all women perceive the woman–midwife relationship to be central to their pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal experiences (Anderson 2000, Bharj 2007, Davies 2000, Edwards 2005, Kirkham 2000, Lundgren & Berg 2007, Walsh 1999). Midwives therefore play an essential role in the life of women during their most significant period and have the power to either augment or mar women’s experiences of pregnancy and childbirth.

Outline of present pattern of maternity services in England

There are a wide range of models of care operating across the UK because of the geographical and demographic variations (Green et al 1998, Wraight et al 1993). The organization of maternity services varies throughout the UK. The maternity and obstetric units are formed as a part of larger district or regional general hospitals and the maternity and midwifery services are normally provided through such units and are integrated within the community and hospital. Midwifery units are designed and staffed according to the birth rates, therefore, the sizes of the units are variable dependent on the birth rates. Some NHS hospitals provide tertiary maternity and neonatal services for part of the regions. Generally, midwifery staff are employed by an acute maternity unit and may work either in the community or in the hospital, or, in some models of care, in both.

Birth settings

There are four different birth settings: ‘consultant-led obstetric units’ (CLU), ‘midwifery-led units’ (MLU), ‘home’, and ‘free-standing maternity units’ (FMU) (Hall 2003) (for choices of place of birth, see Ch. 34). CLUs are usually attached to the district or regional units and deliver care both for women who have complex healthcare needs and for those with no complications of pregnancy, labour and birth. CLUs are staffed by midwives and obstetricians. Women are normally referred to an obstetrician who becomes the lead professional for the duration of their childbirth continuum. Women with complex healthcare needs may access all their care in the antenatal, intranatal and postnatal period within these settings.

MLUs, sometimes known as ‘low-risk maternity units’ (Hall 2003), are often located close to, but separate from, CLUs. These units normally aim to provide care to women with uncomplicated pregnancies; the women, however, have to meet the criteria for the unit throughout pregnancy, labour and birth. MLUs are staffed predominantly by midwives, although they may be jointly run by midwives and GPs. If a deviation from normal is detected during pregnancy, labour or birth, the woman will be referred to an obstetrician, or, if appropriate, a GP, and may have to transfer place of care to the CLU. Normally, women access the majority of their antenatal care in the community setting with minimal care in the hospital setting.

Women may choose to have their babies at home instead of a hospital setting (see Ch. 34). Each of the midwifery units in the UK has its own arrangements for providing a home birth service and its own guidelines and attitudes towards these. The provision of this service depends on local resources, local practices and policies, and the beliefs, skills and commitment of individual practitioners providing the service. Women who choose to have a home birth are normally given care in the community by the lead professional who may be either a midwife or GP. In circumstances where the maternity needs of the woman cannot be managed in the home setting, then she and/or her baby is transferred to the nearest CLU.

To meet the maternity needs of the local populations, two things have happened concomitantly in some areas of England. The move to centralize maternity services has seen a number of mergers and, at the same time, there have appeared a small number of new community units or birth centres to provide a limited service for women who would otherwise have to travel long distances to have their babies in large obstetric units (for example, see Kirkham 2003).

Team midwifery

A variety of approaches to team midwifery are emerging; they strive to provide choice and continuity and these include team midwifery normally based in the community, one-to-one midwifery practice care for women (Green et al 1998, Page et al 2000), that is, a complete episode of care from the booking interview to transfer to the health visitor following birth, including intrapartum care. Other approaches include caseload midwifery, or, as it is sometimes referred to, midwifery group practice. This comprises a small number of midwives organized into a team who are responsible for the delivery of full range of maternity care (SNMAC 1998). The midwives in the team are each responsible for approximately 30–40 women in a year.

While many parts of the UK have some sort of team arrangement for providing maternity services, these teams may vary from two or three midwives to over 30. There is no agreed definition of teams (RCM 2000, SNMAC 1998, Wraight et al 1993) though teams are responsible for providing care in the hospital setting, community settings, or both. There are four possible options of care:

Domiciliary in and out scheme (DOMINO scheme)

A domiciliary in and out scheme (DOMINO scheme) is offered in some areas for women who wish for community-based care (Wardle et al 1997). Within this model, antenatal care is delivered by a community midwife as it would be for a home birth. The community midwife provides care at home during labour, and continues care when the woman is transferred into hospital for birth. Following birth, the woman and her baby, when healthy, are transferred home with postnatal care provided by the community midwife.

Place of birth

During pregnancy, women need unbiased information to consider where they wish to give birth. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 34. The most common place of birth continues to remain the hospital setting and the rate of home births has not changed significantly over the past few decades, despite calls for increasing women’s choice in the place of birth (DH 2007a). Although the rate of home birth remains low, there are marked geographical variations. This appears to depend on midwives and doctors supporting the idea of healthy women having their babies at home. Where this was the case, the numbers of women having home births increased (Sandall et al 2001).

Pattern of care

Historically, irrespective of their personal needs, individual risk status or parity, all pregnant women were encouraged to routinely attend an antenatal clinic every 4 weeks up to 28 weeks’ gestation, then 2-weekly up to 36 weeks, and then weekly thereafter. Evidence in the 1980s suggested that healthy women were at no greater risk of maternal or perinatal mortality if they attended fewer antenatal visits than the historical pattern of care (Hall et al 1985) and in 1982 the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) recommended that maternity care providers should reduce the number of antenatal visits for women who do not have any complications of pregnancy from the historical pattern of 14–16 visits for all women to five to seven visits for multiparous women and eight or nine visits for primiparous women (RCOG 1982). This recommendation was not widely implemented until it was reiterated in the ‘Changing childbirth’ report (DH 1993), where it was suggested that many existing maternity care practices, such as the frequency and timing of antenatal care, had continued as a result of tradition and ritual rather than as a result of evidence of effectiveness. More recently, the NICE guidance (2008) recommended that for nulliparous women with uncomplicated pregnancies, ten antenatal appointments ‘should be adequate’, and that for parous women with uncomplicated pregnancies, seven antenatal appointments ‘should be adequate’. However, 25% of women have reported receiving fewer than the recommended number of antenatal visits (CHAI 2008). Whilst it is acknowledged that a reduction in the frequency of antenatal appointments does not result in an increase in adverse biological maternal and perinatal outcomes (Villar et al 2001), it is not clear whether a reduction in the frequency of antenatal visits affects women’s satisfaction with antenatal care and the social support that they may require. Nevertheless, it is essential that the number of antenatal visits should be tailored to meet women’s individualized health needs instead of attending antenatal appointments in a ritualistic pattern.

Throughout the childbearing period, all women should be provided with the opportunity to discuss issues and to ask questions (NICE 2008). To enable women to make informed choices about their care, midwives need to work in partnership with women and their families to develop and maintain relationships based upon effective communication skills, empathy and trust (Berry 2007). To communicate effectively and discuss matters fully with women, antenatal appointments need to be structured in such a way as to ensure the woman has sufficient time to make informed decisions (NICE 2008) and midwives need to develop the knowledge required to ensure they are able to offer up-to-date, consistent, evidence-based information and clear explanations, using terminology that women and their families are able to understand. Adjustments may need to be made to ensure that women with additional communication needs are able to access information in a format they are able to understand. This may include using interpreters, online resources or DVDs as well as leaflets and books to support discussions.

The first antenatal visit

Whatever the background of the woman, or her reactions to her pregnancy, building a positive relationship with her is one of the midwife’s most important aims during this first antenatal visit. This provides a foundation upon which the trust between a midwife and a woman will be built during the rest of the pregnancy. The woman needs open communication with a midwife who is well informed and committed to supporting her as an individual, encouraging the development of mutual respect, trust and partnership (Nicholls & Webb 2006, Redshaw et al 2007). There is growing evidence of women’s views of the maternity services that consistently highlights the importance of the quality of the women’s relationship with their midwife and the importance of this relationship in their satisfaction levels (CHAI 2008, Redshaw et al 2007).

History taking

An antenatal booking interview should comprise more than merely recording an obstetric history; it should be about communicating information and promoting a relationship between the woman and the midwife (Methven 1982a, 1982b). Factors conducive to a more relaxed atmosphere and which promote communication should be considered, for example, the environment of the setting where the history is going to be taken, arrangements of the furniture in the room, body language and interpersonal skills. A few minutes spent by the midwife in introducing herself and talking informally enable the woman to settle down and relax before personal issues are discussed. A skilled midwife can elicit most of the information required from the woman in a pleasant conversational manner without the woman realizing that she is being closely questioned. Open rather than closed questions should be employed because these encourage free responses and promote two-way interaction between the woman and midwife. During the interview the midwife should be sensitive to the woman’s attitude to her pregnancy and, if possible, to that of her partner. Unusually adverse attitudes and body language should be noted and counselling and support given as required.

Personal details

The woman’s ethnicity is ascertained because some medical and obstetric conditions are more likely to occur in certain ethnic groups and appropriate diagnostic tests are required. However, asking about ethnicity is complex (Dyson 2005) and midwives need to develop competence in accomplishing this sensitively. The religion of the woman is recorded because of the special requirements and rituals which may be practised and affect the mother and her baby. Occupation gives an indication of socioeconomic status. Women in socioeconomic groups IV and V (see website) may experience social and economic inequalities. These wider determinants of health coupled with poverty are most likely to adversely affect their or their fetus’s/baby’s health and clinical outcomes (Lewis 2007, Palmer et al 2008). The midwife needs to work with other agencies to provide the woman and her family with appropriate support to promote and improve her health.

Present pregnancy

The date of the first day of the last menstrual period (LMP) is ascertained, care being taken to check that this was the last normal menstrual period. Some women have a slight blood loss when the fertilized ovum embeds into the decidual lining of the uterus and many mistake this for the last period. Pregnancy has been assumed to last 280 days, and to overcome the irregularity of the calendar a working rule of thumb was devised by Naegele. By counting forwards 9 months and adding 7 days from the first day of the last normal menstrual period, it is possible to arrive at an estimated date of delivery (EDD); alternatively, count back 3 months and add 7 days. This method of calculating the EDD is known as Naegele’s rule. However, as February is a short month and the remaining months have 30 or 31 days, from 280 to 283 days may be added to the date of the LMP. Rosser (2000) states that it is unclear whether the length of pregnancy is affected by social, ethnic or obstetric factors. It is important to explain that it is quite normal for the actual day of delivery to be up to 2 weeks before or after the EDD.

In a 35-day cycle, however, ovulation would occur 21 days after the period; in a 21-day cycle, only 7 days after. Adjustments may be made, therefore, when the woman has a regular long or short cycle. If the cycle is long (for example, 33 days), the days in excess of 28 are added when calculating the EDD (Table 32.2). With a regular short cycle, such as 23 days, the number of days less than 28 is subtracted from the EDD.

Table 32.2 Calculation of the EDD

| Cycle 28 days | Cycle 33 days | Cycle 23 days |

|---|---|---|

| LMP: 12 Aug 2010 | LMP: 12 Aug 2010 | LMP: 12 Aug 2010 |