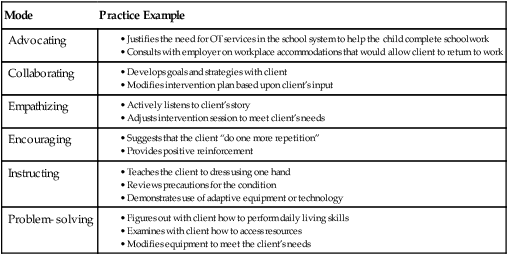

After reading this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following: • Explain the uniqueness of the therapeutic relationship • Describe how “use of self” is used by practitioners • Understand the importance of self-awareness for effective therapeutic relationships • Identify the three “selves” recognized in self-awareness • Explain the skills needed for developing effective therapeutic relationships There is a mystique in occupational therapy that is hard to put into words. When we treat a client and affect something relevant to that person, the magic of our profession comes to light. Whether we are splinting a finger injury, demonstrating an adapted key holder, or instructing in time management, what matters is that the interaction is meaningful to the client. We treat the entire person, not just the isolated injury or diagnosis printed on the referral form. We treat people’s illness experiences, not just their illness. We probe clients’ real-life needs and help them recover their abilities to participate in daily routines. We acknowledge the value of the “blissful ordinariness”5 of a day and help clients return to it. We listen as they tell us about the mundane details of their lives that are disrupted by their injury or illness. We help find ways to return to these activities, and in doing so, we validate the importance of ordinary things in their lives. And when our treatment process is successful, patients return to their “blissful ordinariness” with greater awareness of its value. The mystique of occupational therapy is not easy to articulate. What looks so simple on the surface is actually very complex and powerful. Often, clients understand this intuitively. In these instances, words may not be needed. CYNTHIA COOPER, MFA, MA, OTR/L, CHT The interaction between an occupational therapy (OT) practitioner and a client is termed the therapeutic relationship. Therapeutic relationships differ from everyday relationships, in that therapeutic relationships are key for facilitating the healing and rehabilitation process. Therefore, OT practi-tioners create therapeutic relationships to help clients achieve their desired goals. This chapter examines the uniqueness of the therapeutic relationship by describing this relationship in terms of therapeutic use of self, self-awareness, and trust. Skills practitioners use in developing the relationship are presented including trust, empathy, nonverbal and verbal communication, active listening, and group leadership skills. Sample cases throughout the chapter provide readers with descriptions of how therapeutic relationships are used in practice. People who experience catastrophic trauma or illness, disease, or developmental disorders have emotional and physical needs. Occupational therapy practitioners address both the physical and emotional needs of clients. The profession views clients holistically, meaning that practitioners treat the whole person in an individualized way. This involves understanding the client and his or her motivations, desires, and needs. To understand a client in this way, practitioners create a therapeutic relationship with each client. Through this unique relationship, the practitioner learns how to design activities which are internally motivating and meaningful to a client and best meet the client’s goals.3 Oftentimes it is the practitioner’s ability to develop the therapeutic relationship that contributes to the success of the intervention.3,7 Many clients receiving occupational therapy experience a sense of loss. They may lose function, health, occupations, or time. They may realize that they have a chronic illness that will require their attention. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross defined the universal stages of loss as denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.4 Clients may go through some or all of these stages during the intervention process. The process is dynamic and clients may revisit earlier stages. The OT practitioner recognizes these stages and provides support and opportunities to help clients work through the stages. In every therapy session, the OT practitioner is aware of the client’s needs and uses technical and interaction skills to select responses or courses of action that benefit the client. The therapeutic relationship often makes the difference between a successful and an unsuccessful therapy experience. The practitioner continually assesses his or her interaction skills and makes judgments about how to use the skills to help the client. This process of using one’s interactions for the benefit of another is referred to as “the art of relating” and termed the therapeutic use of self. Therapeutic use of self involves awareness of oneself, including such things as how one communicates, presents, and relates with others.1 Taylor developed the Intentional Relationship Model, which systematically describes therapeutic use of self and the development of modes of interacting with clients for their benefit.7 The Intentional Relationship Model defines six primary interpersonal modes (or styles) used in therapeutic relationships: advocating, collaborating, empathizing, encouraging, instructing, and problem-solving.7 Taylor postulates that the intentional relationship works best when therapists are aware of their modes of interacting and are able to shift modes as needed.7 Taylor provides techniques and exercises to develop skill and awareness in therapeutic use of self. See Box 16-1 for examples of modes. Several principles are basic to therapeutic use of self. First, practitioners must possess a level of self-awareness so that they can mindfully examine their role in the intervention process. Secondly, practitioners learn to develop trust, provide support, actively listen, and empathize. They use genuineness, respect, self-disclosure, trust, and warmth when interacting with clients.2 These qualities are useful in establishing and sustaining therapeutic relationships. Self-awareness refers to knowing one’s own true nature; it is the ability to recognize one’s own behavior, emotional responses, and effect on others. Occupational therapy practitioners learn to be aware of their own strengths and weaknesses in order to better serve clients. Understanding one’s own strengths and limitations allows the practitioner to focus on the other person and adapt one’s behavior and interactions with others. Becoming aware of one’s self requires introspection in terms of the ideal self, the perceived self, and the real self. The ideal self is what an individual would like to be if free of the demands of mundane reality. This aspect is the “perfect self,” with only desirable qualities and with all wants and wishes fulfilled. The ideal self is unrealistic and includes all intention, feeling, and desires. It is not well known to others, although people frequently feel the need to defend the ideal self (though perhaps subconsciously) when others do not acknowledge it. The perceived self is the aspect of self that others see without the benefit of knowing a person’s intentions, motivations, and limitations (i.e., as defined only by outward behavior). Therefore, the perceived self is not the true self. Many times the perceived self is different from the ideal self’s perceptions. The real self is a blending of the internal and external worlds involving intention and action plus environmental awareness. The real self includes the feelings, strengths, and limitations of the person, as well as the reality in which the person exists (his or her environment). Health care professionals work with clients from a variety of cultures and environments. The ability to develop an effective therapeutic relationship requires self-awareness and a variety of skills. These skills and techniques can be refined with practice so that the practitioner is able to work effectively with a variety of clients. Practitioners may need to adjust their techniques and skills to work with clients from other cultures who may perceive things differently from the practitioner. In general, developing and sustaining therapeutic relationships involves the ability to develop trust, demonstrate empathy, understand verbal and nonverbal communication, and use active listening.1,2,7 Practitioners may find that in relating to a client they divulge personal information. While this may be beneficial to the intervention process, practitioners are careful to remember the therapeutic relationship is about the client, not the practitioner.2 Self-disclosure should never be offered when the client is in the middle of a crisis or expressing thoughts.2 The amount and type of information disclosed must be considered; the practitioner does not give his or her address or phone number to a client.

Therapeutic Relationships

Psychology of Rehabilitation

Therapeutic Relationship

Intentional Relationship Model

Basic Therapeutic Use of Self Principles

Self-Awareness

Skills for Effective Therapeutic Relationships

Developing Trust