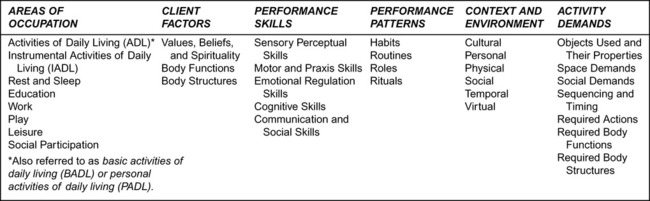

After reading this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following: • Define the domains of occupational therapy (OT) practice • Outline the occupational therapy process • Analyze activities in terms of areas of performance, performance skills, performance patterns, and client factors • Provide examples of how contexts influence occupations The American Occupational Therapy Association developed the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF) as a revision to Uniform Terminology for Occupational Therapy, which provided a unified language for the profession.3 Although Uniform Terminology helped practitioners “speak the same language,” this document did not provide information on the process of providing occupation-based intervention. The OTPF was developed to help practitioners use the language and constructs of occupation to serve clients and educate consumers.1 The goal of occupational therapy is to help clients engage in occupation.1,6,8,9 Occupations are the everyday things that people do and that are essential to one’s identity.1,5,9 The areas of occupation include activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), rest and sleep, education, work, play, leisure, and social participation.1 The following paragraphs provide descriptions of the areas of occupation along with clinical examples. Activities of daily living refer to activities involved in taking care of one’s own body and include such things as dressing, bathing/showering, personal hygiene and grooming, bowel and bladder management, functional mobility, eating, feeding, personal device care, toileting, sexual activity, and sleep/rest.1 Instrumental activities of daily living refer to activities that may be considered optional and involve the environment. IADLs include care of others, care of pets, child rearing, communication device use, community mobility, health management, financial management, home establishment and management, meal preparation and clean up, safety and emergency procedures, religious observance, and shopping.1 The OTPF supports a top-down approach in that the OT practitioner evaluates the areas of performance and occupations in which the client hopes to engage first, followed by an analysis of the performance skills or client factors interfering with performance. This approach differs from reductionistic approaches that analyze components first and subsequently design intervention based upon deficits. The OTPF encourages practitioners to keep occupation central to practice. See Figure 9-1 for an overview of the domain of occupational therapy. Once the practitioner has identified the occupations in which the client would like to engage, the practitioner analyzes performance skills—including motor, process, communication/interaction skills, emotional regulation, sensory, perceptual, and cognitive skills—required to complete the occupation. Performance skills are small units of performance. When an OT practitioner examines performance, he or she identifies performance skills that are effective or ineffective.1 For example, the practitioner may decide that the client’s poor fine-motor skills are interfering with the ability to get dressed in the morning. The client may have difficulty problem-solving how to make breakfast or be unable to make eye contact with peers. These types of performance skills may need to be addressed before the client can engage in desired occupations. Performance skills are dependent upon client factors, activity demands, and context.1 Client factors are even more specific components of performance that may need to be addressed for clients to be successful. Client factors include values, beliefs, spirituality, body functions, and body structures. Client factors include such things as range of motion, strength, endurance, posture, visual acuity, and tactile functions. OT practitioners analyze occupational performance at the basic level so that they can help clients fine-tune their skills and obtain the standards they wish. Patterns of performance are another component of occupational performance analyzed by the OT practitioner. Performance patterns refer to the client’s habits, routines, roles, and rituals.1 Three types of habits are described in the OTPF: useful habits support occupations, impoverished habits do not support occupations, and dominating habits interfere with occupations. Examining performance patterns helps the OT practitioner understand how the occupation is actually accomplished for the individual client. An example of a client with an impoverished habit is one who has difficulty consistently getting up on time and performing morning self-care in a timely manner. As a result of this, the client will have a poorly established or ineffective routine and experience difficulty carrying out his or her desired roles. When choosing an activity to help a client reach his or her goals, OT practitioners also examine the activity demands, which include the objects used and their properties, space demands, social demands, sequencing and timing, required actions, required body functions, and required body structures.1 For example, Mrs. Salazar is a client in occupational therapy who finds the occupation of baking for her family very meaningful. Due to her recent stroke, she has difficulty sequencing the steps for baking a cake. The OT practitioner modifies the demands of the activity by writing each step out very clearly on a sign that is placed in front of Mrs. Salazar while she bakes a cake. Evaluating activity demands allows the OT practitioner to match appropriate activities to the client’s needs and to determine how to modify, adapt, or delete aspects of the activity so the client can be successful. The activity demands change as a result of the context or setting in which the occupation occurs. Context changes the requirements and performance skills, patterns, and demands of the activity. For example, cooking a meal at home for one is much different than having five friends over for a holiday dinner. According to the OTPF, contexts include aspects related to the cultural, personal, physical, social, temporal, and virtual areas.1 See Table 9-1 for definitions of each. Each context must be examined in terms of the demands placed on the occupation. Table 9-1 From American Occupational Therapy Association: Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process, ed 2, Am J Occup Ther 62: 625–683, 2008.

Occupational Therapy Practice Framework

Domain and Process

Areas of Occupation

Activities of Daily Living

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

Analysis of Occupational Performance

Context

Definition

Example

Cultural

Customs, beliefs, activity patterns, behavior standards, and expectations accepted by the society of which the individual is a member. Includes political, such as laws that affect access to resources and affirm personal rights. Also includes opportunities for education, employment, and economic support.

Ethnicity, family, attitude, beliefs, values

Physical

Nonhuman aspects of contexts. Includes the accessibility to and performance within environments having natural terrain, plants, animals, buildings, furniture, objects, tools, or devices.

Objects, built environment, natural environ-ment, geographic terrain, sensory qualities of environment

Social

Availability and expectations of significant individuals, such as spouse, friends, and caregivers. Also includes larger social groups that are influential in establishing norms, role expectations, and social routines.

Relationships with individuals, groups, or organizations; relationships with systems (political, economic, institutional)

Personal

“[F]eatures of the individual that are not part of a health condition or health status.” Personal context includes age, gender, socioeconomic status, and educational status.

25-year-old unemployed man with a high school diploma

Temporal

“Location of occupational performance in time.”12

Stages of life, time of day, time of year, duration

Virtual

Environment in which communication occurs by means of airways or computers and an absence of physical contact.

Realistic simulation of an environment, chat rooms, radio transmissions

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access