Chapter 15

Intervention Modalities

After reading this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

• Identify the principal tools of occupational therapy (OT) practice

• Describe the difference between preparatory, purposeful, simulated, and occupation-based activity

• Describe the use of consultation and education in occupational therapy practice

• Explain the purpose of activity analysis, and describe its application to occupation

• Understand the role of the OT practitioner in the use of physical agent modalities

• Understand the role of the OT practitioner in orthotics and assistive technology

The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF) identifies the four categories of intervention modalities as: (1) therapeutic use of self, (2) therapeutic use of occupations and activities, (3) consultation process, and (4) education process. This chapter describes therapeutic use of occupations and activities, consultation, and education process.2 Therapeutic use of self is described in Chapter 16.

Therapeutic use of occupations and activities includes the use of preparatory, purposeful, and occupation-based activity. OT practitioners help clients reach their goals by using specially designed activities. In using these activities therapeutically, the OT practitioner considers context, activity demands, and client factors as they relate to the goals of the client.2 The consultation process involves working with family and other health professionals to help clients meet their goals. OT practitioners teach and educate others on a variety of topics all designed to enable occupational participation. Thus, the educational process is used during occupational therapy intervention as a way to help clients, families, caregivers, and health care professionals understand and meet client goals to engage in occupations.

Therapeutic Use of Occupations and Activities

OT practitioners use a variety of modalities as tools of the trade. A modality includes both the method of intervention as well as the medium. The steps, sequences, and approaches used to activate the therapeutic effect of a medium are the methods.13 The supplies and equipment used are the media. For example, an OT practitioner might use the medium of a scooter board when treating a child. The OT practitioner may ask the child to use the scooter board in different ways to activate different therapeutic responses. The practitioner may ask the child to ride the board on his stomach down an incline in order to promote extension in the prone position or the practitioner may have the child lie on his back and pull himself on a rope using hand over hand to work on the flexor muscles.

Preparatory Methods

Preparatory methods are used in conjunction with or in order to prepare the client for purposeful activity and occupational performance. They include sensory input, therapeutic exercise, physical agent modalities, and orthotics/splinting.2 These methods address the remediation and restoration of problems associated with client factors and body structure. Preparatory methods support the client’s acquisition of performance skills needed to resume his or her roles and daily occupations.

Sensory Input

Providing sensory input to help a client resume functional movement is considered a preparatory activity. For example, the OT practitioner may stimulate a muscle through vibration in an attempt to activate muscle fibers for contraction and subsequent movement. Using sensory input such as deep pressure may help inhibit abnormal muscle tone in order for the client to engage in purposeful movement.15 Many of these techniques were originated by Margaret Rood, and they help clients prior to the actual activity. Thus, providing sensory input to change muscle tone or sensory sensitivity are considered preparatory activities.

Therapeutic Exercise

Therapeutic exercise, a modality from the biomechanical frame of reference, is the “scientific supervision of exercise for the purpose of preventing muscular atrophy, restoring joint and muscle function, and improving efficiency of cardiovascular and pulmonary function.”14 By understanding the principles of therapeutic exercise, the practi- tioner is able to apply biomechanical principles to purposeful activity. Therapeutic exercise is most effectively used as an intervention for lower motor neuron disorders that result in weakness and flaccidity (e.g., spinal cord injuries, poliomyelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome), or orthopedic conditions such as arthritis.8

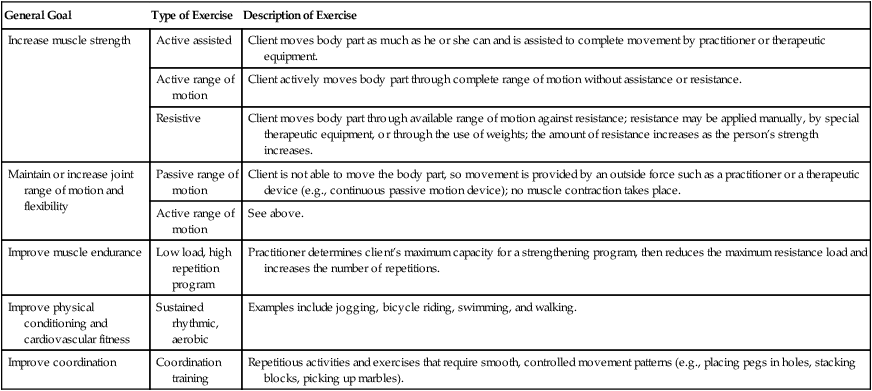

The general goals of therapeutic exercise are to (1) in-crease muscle strength, (2) maintain or increase joint range of motion and flexibility, (3) improve muscle endurance, (4) improve physical conditioning and cardiovascular fitness, and (5) improve coordination. The OT practitioner selects an appropriate therapeutic exercise from available options on the basis of the client’s needs, goals, capabilities, and precautions related to his or her condition.8 Although a description of each therapeutic exercise is beyond the scope of this entry-level text, Table 15-1 provides a summary of the types of therapeutic exercise used for each of the general goals.

Table 15-1

Summary of Types of Therapeutic Exercise

| General Goal | Type of Exercise | Description of Exercise |

| Increase muscle strength | Active assisted | Client moves body part as much as he or she can and is assisted to complete movement by practitioner or therapeutic equipment. |

| Active range of motion | Client actively moves body part through complete range of motion without assistance or resistance. | |

| Resistive | Client moves body part through available range of motion against resistance; resistance may be applied manually, by special therapeutic equipment, or through the use of weights; the amount of resistance increases as the person’s strength increases. | |

| Maintain or increase joint range of motion and flexibility | Passive range of motion | Client is not able to move the body part, so movement is provided by an outside force such as a practitioner or a therapeutic device (e.g., continuous passive motion device); no muscle contraction takes place. |

| Active range of motion | See above. | |

| Improve muscle endurance | Low load, high repetition program | Practitioner determines client’s maximum capacity for a strengthening program, then reduces the maximum resistance load and increases the number of repetitions. |

| Improve physical conditioning and cardiovascular fitness | Sustained rhythmic, aerobic | Examples include jogging, bicycle riding, swimming, and walking. |

| Improve coordination | Coordination training | Repetitious activities and exercises that require smooth, controlled movement patterns (e.g., placing pegs in holes, stacking blocks, picking up marbles). |

Physical Agent Modalities

Physical agent modalities (PAMs) are also considered preparatory methods. PAMs are used to bring about a response in soft tissue and are most commonly used by OT practitioners for treating hand and arm injuries or disorders. PAMs use light, sound, water, electricity, temperature, and mechanical devices to promote changes in function.1 Thermal modalities that involve heat transfer to an injured area (i.e., warm paraffin baths, hot packs, whirlpools, or ultrasound) are used to decrease pain and joint stiffness, increase motion, increase blood flow, reduce muscle spasms, and reduce edema.8 Another thermal modality is the use of cold transfer (i.e., cold packs and ice). Cold transfer is used in the treatment of pain, inflammation, and edema. Electrical modalities include media such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), functional electrical stimulation (FES), and neuromuscular electrical stimulation devices (NMES), and are used to reduce edema, decrease pain, increase motion, and re-educate muscles.8

The use of PAMs in occupational therapy is controversial.1,2,8,10 After debate and discussion, the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) developed a position statement on the use of PAMs that states, “Physical agent modalities may be used by occupational therapists (OTs) and occupational therapy assistants (OTAs) as an adjunct to or in preparation for intervention that ultimately enhances engagement in occupation.” The use of PAMs solely as intervention without application to occupational performance is not considered occupational therapy.1,2 PAMs are not to be used by entry-level practitioners; rather, the practitioner needs to complete specialized post professional training and provide evidence that he or she has the theoretical background and technical skills needed to use PAMs. With proper application, the use of PAMs in occupational therapy allows the practitioner to provide a comprehensive treatment program for the client.8

Orthotics

Any “apparatus used to support, align, prevent, or correct deformities or to improve the function of movable parts of the body”4 is considered an orthotic device, or orthosis. Orthotic devices can be prefabricated or custom made and involve assessing the client, determining the most appropriate orthotic device, designing the device, and evaluating the fit. Orthoses were previously referred to as splints and some practitioners continue to use this term although orthotic is more current and accurately reflects billing codes. OT practitioners train clients in the use of the orthosis, monitor the wearing schedule, and evaluate the client’s response.

Upper extremity orthoses commonly made by OT practitioners (and previously referred to as splints) are “orthopedic devices for immobilization, restraint, or support of any part of the body.”4 They may be rigid or flexible. Three primary purposes of an orthotic device are to (1) restrict movement, (2) immobilize, or (3) mobilize a body part.5 The OT practitioner is expected to recognize when there is a need for an orthosis, select a design that is correct for the problem, fabricate the orthosis, and educate the client in its proper use and care.

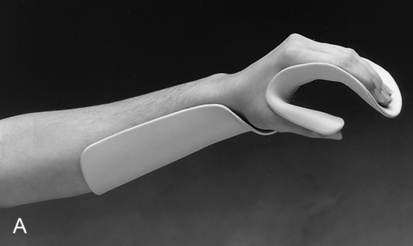

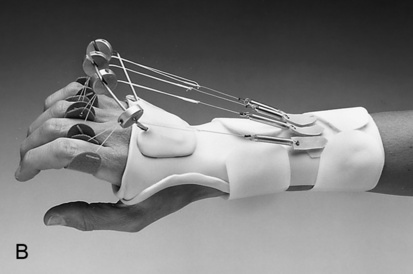

There are two main classifications of orthoses—static and dynamic. The static orthosis has no moving components; as the name implies, it remains in a fixed position. Static orthoses are used to protect or rest a joint, diminish pain, or prevent shortening of the muscle.5 Figure 15-1, A, shows an example of one type of static orthosis. The dynamic orthosis has one or more flexible components that move. The purpose of the dynamic orthosis is to increase passive motion, enhance active motion, or replace lost motion.5 The movable components (elastic, rubber band, or spring) are attached to a static base. Figure 15-1, B, shows an example of a dynamic orthosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree