The Woman with a Postpartum Complication

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

• Explain major causes, signs, and therapeutic management of subinvolution.

• Describe the role of the nurse in the management of women who have a postpartum complication.

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch

Complications that occur during the postpartum period are uncommon, but life threatening. Nurses must be aware of problems that may occur and their effect on the family. The most common physiologic complications are hemorrhage, thromboembolic disorders, and infection. Complications that are psychogenic in origin include postpartum mood disorders and anxiety disorders.

Postpartum Hemorrhage

Postpartum hemorrhage is a major cause of maternal death and morbidity in the United States and the world (Berg, Callaghan, Syverson, et al., 2010). Current literature provides multiple working definitions of postpartum hemorrhage, but no single definition is agreed on and used consistently in the research. Blood loss is frequently underestimated, especially when bleeding is brisk or hemorrhage is concealed. Estimates are frequently only about half the actual loss (Cunningham, Leveno, Bloom, et al., 2010). Current definitions include blood loss of more than 500 mL after vaginal birth or 1000 mL after cesarean birth, a decrease in hematocrit level of 10% or more since admission or the need for a blood transfusion (Cunningham, et al., 2010) and continued bleeding even with the “usual treatment” (Belfort & Dildy, 2011)

Hemorrhage in the first 24 hours after childbirth is called early postpartum hemorrhage. Hemorrhage after 24 hours or up to 6 to 12 weeks after birth, is called late postpartum hemorrhage. Hemorrhage, along with hypertensive disorders, cardiovascular conditions, pulmonary embolism, and infection is a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality (Berg et al., 2010).

Early Postpartum Hemorrhage

Early postpartum hemorrhage usually occurs during the first hour after delivery and is most often caused by uterine atony (Cunningham et al., 2010). Atony refers to lack of muscle tone that results in failure of the uterine muscle fibers to contract firmly around blood vessels when the placenta separates. Trauma to the birth canal during labor and delivery, hematomas (localized collections of blood in a space or tissue), retention of placental fragments, and abnormalities of coagulation are other causes. Hemorrhage from disseminated intravascular coagulation and placenta previa are discussed in Chapter 25. Also, placenta accreta (abnormal adherence of the placenta to the uterine wall) and inversion of the uterus are other causes that are described in Chapter 27.

Uterine Atony

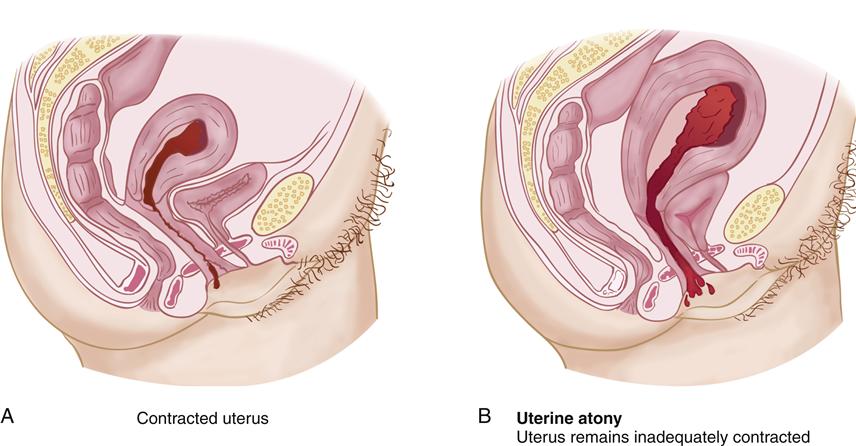

With uterine atony, the relaxed muscles allow rapid bleeding from the endometrial arteries at the placental site. Bleeding continues until the uterine muscle fibers contract to stop the flow of blood. Figure 28-1 illustrates the effect of uterine contraction on the size of the placental site and the amount of bleeding that occurs.

Predisposing Factors

Knowledge of factors that increase the risk of uterine atony helps the nurse anticipate and therefore reduce excessive bleeding. Overdistention of the uterus from any cause, such as multiple gestation, a large infant, and hydramnios, makes it more difficult for the uterus to contract with enough firmness to prevent excessive bleeding. Multiparity results in muscle fibers that have been stretched repeatedly, and these flaccid muscle fibers may not remain contracted after birth. One recent study identified an increase in the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage because of uterine atony in obese women, with the significance of the increase corresponding to increasing body mass index (Blomberg, 2011).

Intrapartum factors include contractions that were minimally effective, resulting in prolonged labor, or contractions that were excessively vigorous, resulting in precipitate labor. Labor that was induced or augmented with oxytocin is more likely to be followed by postdelivery uterine atony and hemorrhage. Retention of a large segment of the placenta does not allow the uterus to contract firmly and therefore can result in uterine atony. Box 28-1 summarizes predisposing factors for postpartum hemorrhage.

Manifestations

Major signs of uterine atony include:

• A uterine fundus that is difficult to locate

• A soft or “boggy” feel when the fundus is located

• A uterus that becomes firm as it is massaged but loses its tone when massage is stopped

• A fundus that is located above the expected level

• Excessive lochia, especially if it is bright red

For the first 24 hours after childbirth, the uterus should feel like a firmly contracted ball roughly the size of a large grapefruit. It should be easily located at about the level of the umbilicus. Lochia should be dark red and scant to moderate in amount. Saturation of one peripad in 15 minutes represents an excessive blood loss (Whitmer, 2011). The nurse must realize that although bleeding may be profuse and dramatic, a constant steady trickle, dribble, or slow seeping is just as dangerous (see Chapter 20 for assessment of the uterus and lochia).

Therapeutic Management

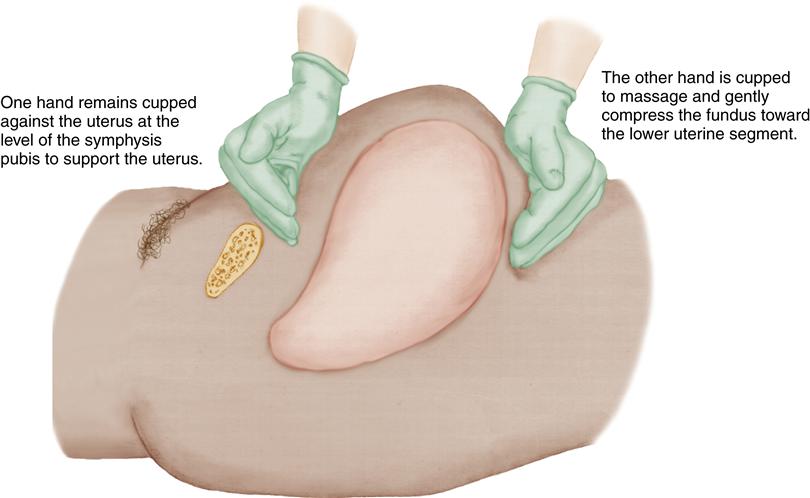

Nurses are with the mother during the hours after childbirth and are responsible for assessments and initial management of uterine atony. If the uterus is not firmly contracted, the first intervention is to massage the fundus until it is firm and to express clots that may have accumulated in the uterus. One hand is placed just above the symphysis pubis to support the lower uterine segment while the other hand gently but firmly massages the fundus in a circular motion. Figure 28-2 illustrates fundal massage.

Clots that may have accumulated in the uterine cavity interfere with the ability of the uterus to contract effectively. They are expressed by applying firm but gentle pressure on the fundus in the direction of the vagina. It is critical that the uterus is contracted firmly before attempting to express clots. Pushing on a uterus that is not contracted could invert the uterus and cause massive hemorrhage and rapid shock (see Chapter 27).

If the uterus does not remain contracted as a result of uterine massage, or if the fundus is displaced, the problem may be a distended bladder. A full bladder lifts the uterus, moving it up and to the side, preventing effective contraction of the uterine muscles. Assist the mother to urinate, or catheterize her to correct uterine atony caused by bladder distention. Note urine output then reassess the uterus.

Pharmacologic measures also may be necessary to maintain firm contraction of the uterus. A rapid intravenous (IV) infusion of dilute oxytocin (Pitocin) often increases uterine tone and controls bleeding (see Drug Guide: Oxytocin, p. 417). Methylergonovine (Methergine) may be given intramuscularly (IM), but it elevates blood pressure and should not be given to a woman who is hypertensive. The usual route of administration is IM; IV use is reserved for life-threatening emergencies only (see Drug Guide: Methylergonovine). Analogs of prostaglandin F2-alpha (PGF2α; carboprost tromethamine [Hemabate; Prostin/15M]) are very effective when given IM or into the uterine muscle if oxytocin is ineffective in controlling uterine atony (Kim, Hayashi, & Gambone, 2010). (See Drug Guide: Carboprost Tromethamine.) Prostaglandin E2 (dinoprostone [Prostin E2]) or misoprostol (Cytotec) given rectally may also be used to control bleeding.

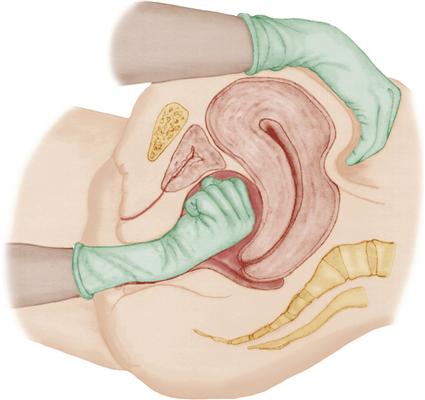

If uterine massage and pharmacologic measures are ineffective in stopping uterine bleeding, the physician or nurse-midwife may use bimanual compression of the uterus. In this procedure, one hand is inserted into the vagina, and the other compresses the uterus through the abdominal wall (Figure 28-3). A balloon may be inserted into the uterus to apply pressure against the uterine surface to stop bleeding (Belfort & Dildy, 2011; Thorp, 2009). Uterine packing may also be used. It may be necessary to return the woman to the delivery area for exploration of the uterine cavity and removal of placental fragments that interfere with uterine contraction.

A laparotomy may be necessary to identify the source of the bleeding. Uterine compression sutures may be placed to stop severe bleeding. Ligation of the uterine or hypogastric artery or embolization (occlusion) of pelvic arteries may be required if other measures are not effective. Hysterectomy is a last resort to save the life of a woman with uncontrollable postpartum hemorrhage.

Hemorrhage requires prompt replacement of intravascular fluid volume. Lactated Ringer’s solution, whole blood, packed red blood cells, normal saline, or other plasma extenders are used. Enough fluid should be given to maintain a urine flow of at least 30 mL/hour and preferably 60 mL/hour (Cunningham et al., 2010). Typically, the nurse is responsible for obtaining properly typed and cross-matched blood and inserting large-bore IV lines that are capable of carrying whole blood.

Trauma

Trauma to the birth canal is the second most common cause of early postpartum hemorrhage. Trauma includes vaginal, cervical, or perineal lacerations as well as hematomas.

Predisposing Factors

Many of the same factors that increase the risk of uterine atony increase the risk of soft tissue trauma during childbirth. For example, trauma to the birth canal is more likely to occur if the infant is large or if labor and delivery occur rapidly. Induction and augmentation of labor and use of assistive devices, such as a vacuum extractor, increase the risk of tissue trauma.

Lacerations

The perineum, vagina, cervix, and the area around the urethral meatus are the most common sites for lacerations. Small cervical lacerations occur frequently and generally do not require repairs. Lacerations of the vagina, perineum, and periurethral area usually occur during the second stage of labor, when the fetal head descends rapidly or when assistive devices such as a vacuum extractor or forceps are used to assist in delivery of the fetal head.

Lacerations of the birth canal should always be suspected if excessive uterine bleeding continues when the fundus is contracted firmly and is at the expected location. Bleeding from lacerations of the genital tract often is bright red, in contrast to the darker red color of lochia. Bleeding may be heavy or may appear to be minor with a steady trickle (dribble or oozing) of blood that continues.

Hematomas

Hematomas occur when bleeding into loose connective tissue occurs while overlying tissue remains intact. Hematomas develop as a result of blood vessel injury in spontaneous deliveries and deliveries in which vacuum extractors or forceps are used. Hematomas may be found in vulvar, vaginal, and retroperitoneal areas.

The rapid bleeding into soft tissue may cause a visible vulvar hematoma, a discolored bulging mass that is sensitive to touch. Hematomas in the vagina or retroperitoneal areas cannot be seen. Hematomas produce deep, severe, unrelieved pain and feelings of pressure that are not relieved by usual pain-relief measures. Formation of a hematoma should be suspected if the mother demonstrates systemic signs of concealed blood loss, such as tachycardia or decreasing blood pressure, when the fundus is firm and lochia is within normal limits.

Therapeutic Management

When postpartum hemorrhage is caused by trauma of the birth canal, surgical repair is often necessary. Visualizing lacerations of the vagina or cervix is difficult, and it is necessary to return the mother to the delivery area, where surgical lights are available. She is placed in a lithotomy position and carefully draped. Surgical asepsis is required while the laceration is being visualized and repaired.

Small hematomas usually reabsorb naturally. Large hematomas may require incision, evacuation of the clots, and location of the bleeding vessel so that it can be ligated.

Late Postpartum Hemorrhage

The most common causes of late postpartum hemorrhage are subinvolution (delayed return of the uterus to its nonpregnant size and consistency) and fragments of placenta that remain attached to the myometrium when the placenta is delivered. Clots form around the retained fragments, and excessive bleeding can occur when the clots slough away several days after delivery. Infection of the uterus may also be a cause. Subinvolution is discussed on p. 673.

Late postpartum hemorrhage caused by retained placental fragments is generally preventable. When the placenta is delivered, the nurse-midwife or physician carefully inspects it to determine whether it is intact. If a portion of the placenta is missing, the health care provider manually explores the uterus, locates the missing fragments, and removes them.

Late postpartum hemorrhage, also called secondary postpartum hemorrhage, is defined as hemorrhage occurring between 24 hours and 6 weeks after birth (Ambrose & Repke, 2011). It frequently happens after discharge from the facility and can be dangerous for the unsuspecting mother. (Women must be taught how to assess the fundus and normal characteristics and duration of lochia flow. They should be instructed to notify their health care provider if bleeding persists or becomes unusually heavy.)

Predisposing Factors

Attempts to deliver the placenta before it separates from the uterine wall, manual removal of the placenta, placenta accreta (see Chapter 27), previous cesarean birth, and uterine leiomyomas are primary predisposing factors for retention of placental fragments.

Therapeutic Management

Initial treatment for late postpartum hemorrhage is directed toward control of the excessive bleeding. Oxytocin, methylergonovine, and prostaglandins are the most commonly used pharmacologic measures. Placental fragments may be dislodged and swept out of the uterus by the bleeding, and if the bleeding subsides when oxytocin is administered, no other treatment is necessary. Sonography can identify placental fragments that remain in the uterus. If bleeding continues or recurs, dilation and curettage, stretching of the cervical os to permit suctioning or scraping of the walls of the uterus, may be necessary to remove fragments. Broad-spectrum antibiotics may be given if postpartum infection is suspected because of uterine tenderness, foul-smelling lochia, or fever.

Hypovolemic Shock

During and after giving birth, the woman can tolerate blood loss that approaches the volume of blood added during pregnancy (approximately 1500 to 2000 mL). A woman who was anemic before birth has less reserve than a mother with normal blood values. The amount of blood lost can be estimated by comparing the hematocrit before labor and delivery with one measured after delivery. If the hematocrit is lower after delivery, the woman lost the amount of blood added during pregnancy and an additional 500 mL for each 3% drop in the hematocrit value (Cunningham et al., 2010).

When blood loss is excessive, hypovolemic shock (acute peripheral circulatory failure resulting from loss of circulating blood volume) can ensue. Hypovolemia, abnormally decreased volume of circulating fluid in the body, endangers vital organs by depriving them of oxygen. The brain, heart, and kidneys are especially vulnerable to hypoxia and may suffer damage in a brief period.

Pathophysiology

Recognition of hypovolemic shock may be delayed because the body activates compensatory mechanisms that mask the severity of the problem. Carotid and aortic baroreceptors are stimulated to constrict peripheral blood vessels. This shunts blood to the central circulation and away from less essential organs, such as the skin and extremities. The skin becomes pale and cold, but cardiac output and perfusion of vital organs are maintained.

In addition, the adrenal glands release catecholamines, which compensate for decreased blood volume by promoting vasoconstriction in nonessential organs, increasing the heart rate, and raising the blood pressure. As a result, blood pressure remains normal initially, although a decrease in pulse pressure (difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressures) may be noted. The tachycardia that develops is an early sign of compensation for excessive blood loss.

As shock worsens, the compensatory mechanisms fail, and physiologic insults spiral. Inadequate organ perfusion and decreased cellular oxygen for metabolism result in a buildup of lactic acid and the development of metabolic acidosis. Decreased serum pH (acidosis) results in vasodilation, which further increases bleeding. Eventually, circulating volume becomes insufficient to perfuse cardiac and brain tissue. Cellular death occurs as a result of anoxia, and the mother dies.

Manifestations

Early signs of blood loss such as mild tachycardia or hypotension may not appear until 20% to 25% of the woman’s blood volume has been lost (Martin & Foley, 2009). Tachycardia is one of the earliest signs of hypovolemic shock, and even gradual increases in the pulse rate should be noted. A decrease in blood pressure and narrowing of pulse pressure occur when the circulating volume of blood is sufficiently decreased. The respiratory rate increases as the woman becomes more anxious and attempts to take in more oxygen to overcome the need that is created when hemoglobin is inadequate to transport oxygen adequately.

Skin changes also provide early clues. Vasoconstriction in the skin causes it to become pale and cool to the touch. As hemorrhage worsens, the skin changes become more obvious as pallor increases and the skin becomes cold and clammy.

As shock progresses, changes also occur in the central nervous system. The mother becomes anxious, then confused, and finally lethargic as blood loss increases. Urine output also decreases and eventually stops.

Therapeutic Management

The goals of therapy are to control bleeding and prevent hypovolemic shock from becoming irreversible. A second IV line should be inserted with a large-bore (14- to 18-gauge) catheter capable of carrying whole blood. Central IV catheters may be placed. Sufficient fluid volume is infused to produce a urinary output of at least 30 mL/hour. Vasopressors may be needed for low blood pressure. The health care team makes every effort to locate the source of bleeding and to stop the loss of blood. Interventions may include uterine packing; ligation of the uterine, ovarian, or hypogastric artery; or hysterectomy.

Nursing Considerations

Immediate Care

One person should be assigned to evaluate and record vital signs. Blood pressure and pulse should be assessed every 3 to 5 minutes. The location and consistency of the fundus, amount of lochia, skin temperature and color, and capillary return also are assessed. Oxygen may be administered by tight face mask at 8 to 10 L/min to increase the saturation of fewer red blood cells. Oxygen saturation levels are carefully monitored. Nurses often follow facility protocols that allow them to draw blood for hemoglobin, hematocrit, clotting studies, and type and cross match. Nurses are responsible for administering fluids, whole blood, and medications as directed and for reporting their effectiveness. A urinary catheter is inserted to measure hourly urinary output, which should be at least 30 mL/hour. The catheter is also necessary if a surgical procedure to control the hemorrhage is required. In addition, nurses must make every effort to provide information and emotional support to the woman and her family.

Nursing Care

The Woman with Excessive Bleeding

Assessment

The initial postpartum assessment includes a chart review to determine whether prolonged labor, birth of a large infant, use of vacuum extractor or forceps, or other risk factors for hemorrhage are present. This alerts the nurse to women at increased risk for hemorrhage.

Uterine Atony

Priority assessments for uterine atony include the fundus, bladder, lochia, vital signs, skin temperature, and color. Assess the consistency and the location of the uterine fundus. The fundus should be firmly contracted, at or near the level of the umbilicus and midline. If the fundus is above the level of the umbilicus and displaced, a full bladder may be the cause of excessive bleeding. A full bladder lifts the uterus and impedes contraction, which allows excessive bleeding. An accumulation of clots also expands the uterus, making contraction difficult and resulting in continued bleeding. (See Procedure: Assessing the Uterine Fundus in Chapter 20 on p. 442 for assessing the fundus.)

Obese women have an increased risk for uterine atony with subsequent postpartum hemorrhage (Blomberg, 2011), however, assessment of the fundus is difficult in this population. Monitor these women frequently for other signs of uterine atony and attempt to assess the uterine fundus while watching for increased lochia flow or clots to be expelled.

Also remember to check under the woman’s legs, buttocks, and back for lochia drainage by asking the woman to turn on her side. This allows visibility of any blood that may not be obvious from the front. Although bleeding may be profuse and dramatic, a continuing small but steady trickle or oozing may also lead to significant blood loss that becomes increasingly life threatening.

It is difficult to estimate the volume of lochia by visual examination of peripads. More accurate information is obtained by weighing peripads, linen savers, and, if necessary, bed linens, before and after use and subtracting the difference. One gram (weight) equals approximately 1 mL (volume).

Measure vital signs at least every 15 minutes or more often, if necessary. Apply a pulse oximeter to determine oxygen saturation levels. This helps to detect trends, such as tachycardia or a decrease in pulse pressure that may reveal a deteriorating status in a woman with significant blood loss. Initially, the body compensates for excessive bleeding by constricting the peripheral blood vessels and shunting blood to vital organs. This can be misleading because the vital signs may remain normal even when the woman is becoming hypovolemic. The skin should be warm and dry, mucous membranes of the lips and mouth should be pink, and capillary return should occur within 3 seconds when the nails are blanched. These signs confirm adequate circulating volume to perfuse the peripheral tissue.

Trauma

If the fundus is firm but bleeding is excessive, the cause may be lacerations of the cervix or birth canal. Inspect the perineum to determine whether a laceration is visible in that area. Lacerations of the cervix or vagina are not visible, but bleeding in the presence of a firmly contracted uterus suggests a laceration. This sign warrants examination of the vaginal walls and the cervix by the health care provider.

Assess comfort level. If the mother complains of deep, severe pelvic or rectal pain or if vital signs or skin changes suggest hemorrhage but excessive bleeding is not obvious, the cause may be concealed bleeding and the formation of a hematoma. Examine the vulva for bulging masses or discoloration of the skin. However, a hematoma developing in the vagina or in the retroperitoneal area will not be obvious when the vulva is examined. Table 28-1 summarizes assessments, abnormal signs and symptoms, and nursing implications.

TABLE 28-1

NURSING ASSESSMENTS FOR POSTPARTUM HEMORRHAGE

| ASSESSMENTS | ABNORMAL SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS | NURSING IMPLICATIONS |

| Chart review | Presence of predisposing factors | Perform more frequent evaluations. |

| Fundus | Soft, boggy, displaced | Massage, express clots, and assist to void or catheterize; notify primary health care provider if measures are ineffective. |

| Lochia | Bleeding (steady trickle, dribble, oozing, seeping, or profuse flow); heavy: saturation of 1 pad/hr; excessive: 1 pad/15 min | Assess for trauma; save and weigh pads, linen savers, and bed linens so estimation of blood loss will be more accurate. Notify health care provider. |

| Vital signs | Tachycardia, decreasing pulse pressure, falling blood pressure, decreasing oxygen saturation level | Report signs of excessive blood loss. |

| Urine output | Decreased urine output | Report decrease in output. |

| Should be at least 30 mL/hr | ||

| Comfort level | Severe pelvic or rectal pain | Assess for signs of hematoma, usually perineal or vaginal; examine vulva for masses or discoloration; report findings. |

| Skin | Cool, damp, pale | Look for signs of hypovolemia; vigilant assessment and management by entire health care team is necessary. |

Nursing Diagnosis and Planning

Postpartum hemorrhage is a complication that requires the efforts of all members of the health care team to control the hemorrhage and prevent further complications such as hypovolemic shock. Patient-centered goals are inappropriate for this potential complication because the nurse cannot manage postpartum hemorrhage independently but must use orders from the physician or nurse-midwife to treat the condition. Planning should reflect the nurse’s responsibility to:

Interventions

Preventing Hemorrhage

The key to successful management of early postpartum hemorrhage is early recognition and response. All postpartum women are at risk for hemorrhage. However, always be aware of factors that increase this risk further and be particularly vigilant in monitoring these women so that excessive bleeding can be anticipated and minimized.

When predisposing factors are present, initiate frequent assessments. Many hospitals and birth centers have a standard of care that calls for assessments every 15 minutes during the first hour after delivery, every 30 minutes for the next 2 hours, and hourly for the next 4 hours. This plan may not be adequate for the woman at known risk for postpartum hemorrhage because bleeding occurs rapidly. A delay in assessment could result in a great deal of blood loss.

Collaborating with the Health Care Provider

When excessive bleeding is suspected and the fundus is boggy, begin uterine massage. Check the woman’s bladder for distention and have her empty it if necessary. If she is not able to void, and the bladder is distended, catheterize the woman. Many facilities have protocols for catheterization of postpartum women. If not, obtain an order for this procedure. Weigh blood-soaked pads, linen savers, and linens to accurately determine the amount of blood lost. If massage is not effective in controlling bleeding promptly, notify the physician or nurse-midwife. Save any tissue or clots passed.

Most facilities also have protocols that permit nurses to initiate specific laboratory studies, such as determining hemoglobin and hematocrit levels and typing and crossmatching blood, so that blood is available should transfusions become necessary. Coagulation studies that may be ordered include fibrinogen, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, fibrin split products, fibrin degradation products, platelets, D dimer, and blood chemistry. Many protocols also allow the nurse to increase the flow rate of an existing IV or insert a large-bore catheter to start IV fluids while the health care provider is being informed of the mother’s condition. These actions do not substitute for notifying the health care provider, but they do allow nurses to make initial interventions quickly.

Keep the woman on bed rest to increase venous return and maintain cardiac output. The full Trendelenburg’s position may interfere with cardiac and pulmonary function and is not advised. A modified Trendelenburg position may be used with the legs elevated 10 to 30 degrees to increase blood return from the legs, the trunk horizontal, and the head slightly elevated. Continue assessments, call for assistance, and save all blood-soaked materials so that an accurate estimation of blood loss can be made. Assistance is necessary, because one nurse must continue to massage the uterus and perform and record assessments while another notifies the health care provider of the mother’s condition and gathers medications and supplies needed.

When notifying the provider, document the time and content of each communication. For example, “1300: Dr. X notified of implementation of postpartum hemorrhage protocol due to difficulty maintaining uterine contraction and continued excessive bleeding. Requested Dr. X to see patient now.”

Administer medications, fluids, and treatments as ordered by the health care provider or as stated in the facility’s protocol. Note the effects and relay the information to the health care provider. Physicians and nurse-midwives depend on the nurse for accurate information, and they base medical management on information relayed by the nurse.

Because of oxytocin’s antidiuretic effect, listen to breath sounds to identify signs of pulmonary edema from fluid overload if large amounts of oxytocin are given. Document blood pressure if methylergonovine (Methergine) is given. If measures fail to control bleeding, notify the health care provider so that additional procedures can be initiated. These may include preparation for operative intervention (surgical preparation, consent signed for operative procedure, or confirmation that blood replacement is available).

Providing Support for the Family

The unusual activity of the hospital staff may make the mother and her family anxious. Be alert to their nonverbal cues, and when they appear frightened acknowledge their feelings. Keeping the family informed is one of the most effective ways of reducing anxiety.

Posthemorrhage Care

After the hemorrhage is controlled, continue to assess the woman frequently for a resumption of bleeding. The woman may be anemic and fatigued. Allow rest periods and organize work to help her conserve energy. Because the woman may experience orthostatic hypotension, assist her in getting out of bed after dangling her legs and assess for dizziness and low blood pressure. Encourage intake of fluids and of foods high in iron. She may need assistance feeding her newborn.

Home Care

Nurses who work in home care or nurse-managed postpartum clinics must be aware that women who have had postpartum hemorrhage are subject to a variety of complications. In general, they are exhausted, and it may take weeks for them to feel well again. Anemia often results, and a course of iron therapy may be prescribed to restore hemoglobin level. Activity may be restricted until strength returns. Some women need extra assistance with housework and care of the new infant. Fatigue may interfere with bonding and attachment. Because extensive blood loss increases the risk of postpartum infection, the woman must be taught to observe for specific signs and symptoms.

Evaluation

Although patient-centered goals are not developed for potential complications (collaborative problems), the nurse collects and compares data with established norms and judges whether the data are within normal limits. If problems arise, the nurse acts to minimize hemorrhage and notifies the health care provider.

Subinvolution of the Uterus

Subinvolution refers to a slower-than-expected return of the uterus to its nonpregnant size after childbirth. Normally the uterus descends at the rate of approximately 1 cm or one fingerbreadth per day. By 14 days, it is no longer palpable above the symphysis pubis. The endometrial lining has sloughed off as part of the lochia, and the site of placental attachment is well healed by 6 weeks after childbirth if involution progresses as expected.

The most common causes of subinvolution are retained placental fragments and pelvic infection. Signs of subinvolution include prolonged discharge of lochia, irregular or excessive uterine bleeding, and sometimes profuse hemorrhage. Pelvic pain or feelings of pelvic heaviness, backache, fatigue, and persistent malaise are reported by many women. On bimanual examination, the uterus feels larger and softer than normal for that time of the puerperium.

Therapeutic Management

Treatment is tailored to correct the cause of subinvolution. Methylergonovine maleate (Methergine) given orally provides long, sustained contraction of the uterus. Infection responds to antimicrobial therapy.

Nursing Considerations

In most cases, subinvolution is not obvious until the mother has returned home after childbirth. For this reason, nurses must teach the mother and her family how to recognize its occurrence.

The mother is taught how to locate and palpate the fundus and how to estimate fundal height in relation to the umbilicus. The uterus should become smaller each day (by approximately one fingerbreadth). Also, explain the progressive changes from lochia rubra, to lochia serosa, and then to lochia alba (see Chapter 20).

The mother is instructed to report any deviation from the expected pattern or duration of lochia. A foul odor often indicates uterine infection, for which treatment is necessary. Additional signs include pelvic or fundal pain, backache, and feelings of pelvic pressure or fullness. The mother should be able to verbalize the warning signs prior to leaving the facility.

Thromboembolic Disorders

A thrombus is a collection of blood factors, primarily platelets and fibrin, on a vessel wall. Thrombophlebitis occurs when the vessel wall develops an inflammatory response to the thrombus. This further occludes the vessel. An embolus is a mass that may be composed of a thrombus or amniotic fluid released into the bloodstream that may cause obstruction of capillary beds in another part of the body, frequently the lungs. A pulmonary embolus is a potentially fatal complication that occurs when the pulmonary artery is obstructed by a blood clot that was swept into circulation from a vein or by amniotic fluid. The three most common thromboembolic disorders encountered during pregnancy and the postpartum period are superficial venous thrombophlebitis (SVT), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and, occasionally, pulmonary embolism (PE). SVT generally involves the saphenous venous system and is confined to the lower leg. DVT can involve veins from the foot to the iliofemoral region. It is a major concern because it predisposes to PE.

Incidence and Etiology

Thromboembolic disorders are the leading cause of maternal mortality in the United States (Rhode, 2011). Thrombi can form whenever the flow of blood is impeded. Once started, the thrombus can enlarge with successive layering of platelets, fibrin, and blood cells as the blood flows past the clot. Thrombus formation is often associated with thrombophlebitis.

The three major causes of thrombosis are venous stasis, hypercoagulable blood, and injury to the endothelial surface (the innermost layer) of the blood vessel. Two of these conditions—venous stasis and hypercoagulable blood—are present in all pregnancies, and the third, blood vessel injury, is likely to occur during birth.

Venous Stasis

During pregnancy, compression of the large vessels of the legs and pelvis by the enlarging uterus causes venous stasis. Stasis is most pronounced when the pregnant woman stands for prolonged periods of time. It results in dilated vessels that increase the potential for continued pooling of blood postpartum. Relative inactivity and activity restriction caused by complications during pregnancy lead to venous pooling and stasis of blood in the lower extremities. Prolonged time in stirrups for delivery and repair of the episiotomy also may promote venous stasis and increase the risk of thrombus formation.

Hypercoagulation

Pregnancy is characterized by changes in the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems that persist into the postpartum period. During pregnancy, the levels of many coagulation factors are elevated. In addition, the fibrinolytic system, which causes clots to disintegrate (lyse), is suppressed. The result is that factors that promote clot formation are increased, and factors that prevent clot formation are decreased to prevent maternal hemorrhage, resulting in a higher risk for thrombus formation during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

Blood Vessel Injury

Vascular damage is a potential during pregnancy, especially at birth. Lower extremity trauma, operative delivery, and prolonged labor can cause vascular damage (Rhode, 2011). Cesarean birth significantly increases the risk for thromboembolic disease (Dizon-Townson, 2010).

Additional Predisposing Factors

Women with varicose veins, obesity, a history of thrombophlebitis, and smoking are at additional risk for thromboembolic disease (Box 28-2). Age older than 35 years doubles the risk (Lockwood, 2009).

Superficial Venous Thrombosis

Manifestations

SVT is most often associated with varicose veins and limited to the calf area. It can also occur in the arms as a result of IV therapy. Signs and symptoms include swelling of the involved extremity as well as redness, tenderness, and warmth. It may be possible to palpate an enlarged, hardened, cordlike vein. The woman may experience pain when she walks, but some women have no signs at all.

Therapeutic Management

Treatment includes analgesics, rest, and elastic support. Elevation of the lower extremity improves venous return. Warm packs may be applied to the affected area. Anticoagulants are not needed but antiinflammatory medications may be used. After a period of bed rest with the leg elevated, the woman may ambulate gradually if symptoms have disappeared. She should avoid standing for long periods and should continue to wear support hose to help prevent venous stasis and a subsequent episode of superficial thrombosis. There is little chance of PE if the thrombosis remains in the superficial veins of the lower leg.

Deep Venous Thrombosis

Signs and symptoms of DVT or PE are absent in 75% of those affected (Lockwood, 2009). When present, they may be attributed to normal benign changes of pregnancy (Farquharson & Greaves, 2011). Those that occur are caused by an inflammatory process and obstruction of venous return. The woman may report pain in the leg, groin, or lower back or right lower quadrant pain (Rhode, 2011). Swelling of the leg (more than 2 cm larger than the opposite leg), erythema, heat, and tenderness over the affected area are the most common signs. A positive Homans sign (presence of leg pain when the foot is dorsiflexed) has been thought to be an indicator of DVT. However, Homans sign may be absent in women who have a venous thrombosis or may be caused by a strained muscle or bruise. It is not a reliable or valid test. Reflex arterial spasms may cause the leg to become pale and cool to the touch with decreased peripheral pulses. Additional symptoms may include pain on ambulation, chills, general malaise, and stiffness of the affected leg.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Venous ultrasonography with vein compression and Doppler flow analysis of the deep veins of the upper legs are most commonly used to detect alterations in blood flow that are diagnostic of DVT. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered very sensitive and accurate in diagnosing pelvic and leg thrombosis (Lockwood, 2009). d-dimer tests may be performed, but the results are normally higher during pregnancy and postpartum, and the test may not be as accurate as at other times. A negative result has a very high predictive value, therefore a d-dimer test may be used to rule out a thrombus in low-risk women. If the test is positive, it is followed by venous ultrasound (Lockwood, 2009).

Therapeutic Management

Preventing Thrombus Formation

Women who have had a previous DVT or PE are at risk for another. These women and others at high risk may receive prophylactic heparin, which does not cross the placenta. Either standard unfractionated heparin (UH) or a low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), such as enoxaparin (Lovenox) or tinzaparin (Innohep), may be used. LMWH is longer acting and can be given less frequently and with less laboratory testing. It has fewer side effects and is less likely to cause bleeding. However, it is more expensive than UH and must be given subcutaneously. UH is given IV or subcutaneously.

Women receiving LMWH during pregnancy are changed to UH at approximately 36 weeks of gestation. The change is necessary because UH has a shorter half-life, and epidural anesthesia, which may be needed in labor, is contraindicated within 24 hours of the last dose of LMWH. Heparin is discontinued during labor and birth and resumed approximately 6 to 12 hours after uncomplicated birth and 12 hours after the epidural catheter is removed (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2011).

If stirrups must be used during the birth, risks of thrombus development can be reduced by placing the woman’s legs in stirrups that are padded to prevent prolonged pressure against the popliteal angle during the second stage of labor. If possible, the time in stirrups should be no more than 1 hour.

To prevent thrombus formation after childbirth, all new mothers are encouraged to ambulate frequently and as early as possible. Ambulation prevents stasis of blood in the legs and decreases the likelihood of thrombus formation. If the woman is unable to ambulate, range-of-motion and gentle leg exercises, such as flexing and straightening the knee and raising one leg at a time, should begin within 8 hours after childbirth. In addition, the mother should not use pillows under her knees or the knee gatch on the bed. These devices may cause sharp flexion at the knees and pressure against the popliteal space, leading to pooling of blood in the lower extremities.

Graduated compression stockings or sequential compression devices are used for mothers with varicose veins, a history of thrombosis, or a cesarean birth. Sequential compression devices should be applied preoperatively for a woman undergoing a cesarean birth who is not on anticoagulant therapy and should be continued until she begins to ambulate postpartum (ACOG, 2011). Compression stockings should be applied before the mother gets out of bed to prevent venous congestion, which begins as soon as she stands. It is important that she understands the correct way to put on the stockings. Improperly applied stockings can roll or bunch and slow venous return from the legs.

Initial Treatment

Anticoagulant therapy is started to prevent extension of the thrombus. Therapy may begin with a continuous infusion of IV UH that is later changed to subcutaneous UH. The activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) should be monitored, and the heparin dose adjusted to maintain a therapeutic level of 1.5 to 2.5 times the control (Castro & Ogunyemi, 2010). Subcutaneous LMWH may be used instead of UH and requires less frequent laboratory monitoring. Antifactor Xa and platelets may be monitored if LMWH is used.

The woman is placed on bed rest, with the affected leg elevated to decrease interstitial swelling and to promote venous return from the leg. She is allowed to ambulate when symptoms have disappeared. Analgesics may be prescribed to control pain and antibiotics will be used as necessary to prevent or control infection. Moist heat provides relief of pain and increases circulation.

Subsequent Treatment

The long-term management of DVT depends on whether the woman is pregnant or in the postpartum period. The pregnant woman with a DVT receives anticoagulation therapy until labor begins. It is resumed 6 to 12 hours after birth and continued for 6 weeks to 6 months after birth (ACOG, 2011). Warfarin (Coumadin) is contraindicated during pregnancy because of teratogenic effects and the risk of fetal hemorrhage. Therefore, pregnant women are given UH or LMWH, which do not cross the placenta.

During the postpartum period, warfarin is started before heparin is stopped to provide continuous anticoagulation. Heparin is discontinued when the international normalized ratio (INR) has been at therapeutic levels for 2 days. Warfarin therapy is continued for at least 6 weeks postpartum (Ambrose & Repke, 2011). Warfarin is safe for use during lactation. Longer use of warfarin is necessary in some women with continuing risk factors. The INR is used to monitor coagulation time when warfarin is used.

Before discharge from the birth facility, the mother should be taught about lifestyle changes that can improve peripheral circulation. This includes avoiding clothing that is constricting around the legs and prolonged sitting. If sitting for long periods is necessary, walking for a short time hourly or moving her feet and legs frequently will help prevent circulatory stasis.

Nursing Care

The Mother with Deep Venous Thrombosis

Assessment

Assessment focuses on determining the status of the venous thrombosis. Inspect both legs at the same time so that the affected leg can be compared with the unaffected leg. DVT is most often unilateral, usually affecting the woman’s left side (Lockwood, 2009). Warmth or redness indicates inflammation; coolness or cyanosis indicates venous obstruction. Palpate the pedal pulses, comparing the strength of the right and left. Measure the affected and unaffected leg comparing the circumferences to obtain an estimation of the edema. Record the measurements for ongoing assessment. It may be helpful to mark the woman’s legs at the location of the measurement for consistency in assessments. Ask the woman about the degree of her discomfort. Pain is caused by tissue hypoxia, and increasing pain indicates progressive obstruction.

Evaluate the laboratory reports of clotting studies. In addition to activated partial thromboplastin time, platelets may be evaluated when UH is used. Thrombocytopenia is a concern when heparin is administered for a prolonged time. The INR is evaluated when the anticoagulant for the postpartum woman is changed to warfarin.