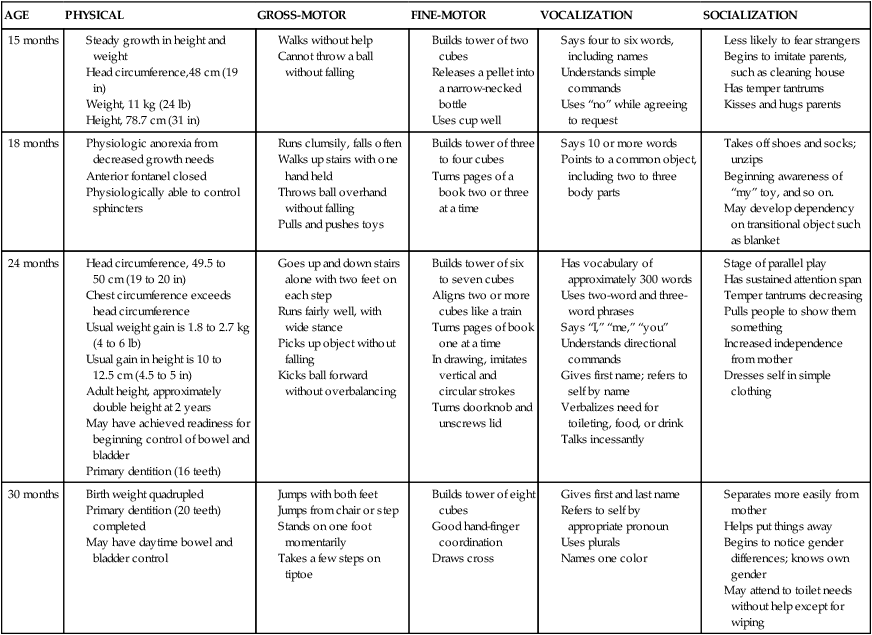

1. Define the vocabulary terms listed 2. Describe the physical and psychosocial development of children from 1 to 3 years of age, listing age-specific events and guidance when appropriate 3. Discuss how adults can help small children combat their fears 4. Identify five strategies that aid in meeting a toddler’s nutritional needs 5. Identify the principles of toilet training (bowel and bladder) that assist in guiding parents’ efforts to provide toilet independence 6. Discuss questions to use in evaluation of daycare centers 7. Discuss the use of car seats for toddlers 8. Identify four potential safety hazards specific to the toddler and anticipatory guidance for caretakers in preventing such accidents 9. Discuss care of the child with poisonings (acetaminophen, ibuprofen, aspirin, lead, hydrocarbons, and corrosives) Children between 1 and 3 years of age are referred to as toddlers. They are able to move about on their own and are no longer completely dependent persons. By 1 year of age, they have generally tripled their birth weight and gained control of their head, hands, and feet. The remarkably rapid growth and development that occurred during infancy begins to slow. The toddler period presents different challenges for parents and children. This chapter discusses what toddlers are like as people and some of the obstacles they face (Table 7-1). Table 7-1 Summary of Toddler Growth and Development Head circumference, 49.5 to 50 cm (19 to 20 in) Chest circumference exceeds head circumference Usual weight gain is 1.8 to 2.7 kg (4 to 6 lb) Usual gain in height is 10 to 12.5 cm (4.5 to 5 in) Adult height, approximately double height at 2 years May have achieved readiness for beginning control of bowel and bladder Modified from Hockenberry, M., and Wilson, D. (2007). Wong’s nursing care of infants and children (8th ed.). St. Louis: Elsevier. Toddlers are curious explorers who get into everything. As each month passes, they gain more control of their bodies. Soon they are walking, running, jumping, and climbing (Figure 7-1). They enjoy repeating these new skills, and with practice, they become less clumsy and awkward. Their desire to touch, taste, smell, and smear leads them into trouble. They quickly discover that much of their conduct alarms their parents. Unlike when they were infants, toddlers find that their parents no longer accept their actions willingly and without question. Toddlers cannot understand the need for restrictions, and, as a result, they revolt. Temper tantrums are common, and behavior is not consistent. Negativism is reflected in unreasonable behavior and by saying “no” frequently. Ritualism is characteristic of toddlers. By making simple tasks into rituals, they increase their sense of security and self-mastery. Dawdling serves essentially the same purpose, and egocentric thinking predominates. The developmental tasks seen during this period are based on a continuum of trust established during infancy. Physicians and nurse practitioners can readily focus on age-related tasks at the toddler’s well-visit. Toddlers are now ready to give up total dependence. They become autonomous and seek independence (see discussion on Erikson in Chapter 4). They begin to differentiate themselves from others, particularly from their mother. They learn to delay gratification and to incorporate rudiments of socially acceptable behavior as determined by the limits of their family’s culture. Important self-regulatory functions include toilet independence, eating, sleeping, and perfection of new-found physical skills. Separation continues to be a major issue with this age group. Toddlers are beginning to separate somewhat from their parents but can tolerate only brief periods of independence and still remain very interested in knowing where their parents are (Figure 7-2). Their greatest fear is separation from their parents. They need to be reassured that when their parents leave, they will return. The younger toddler might exhibit night waking as a response to fear of separation. This same child might use a transitional object (blanket, toy) for consolation when separated from the parent. By 2 years of age, the child still gets upset when separated from the parents, although not as much as before. The nurse should be reminded that separation fears are increased when a child is under stress. So the hospitalized child needs to be supported if the parents are unable to stay. Parents should never “sneak out” on a child. Mastering separation is a normal developmental process. The gradual control of these activities provides toddlers with a sense of mastery and contributes to their positive self-concept. The toddler is more capable of maintaining a stable body temperature than is the infant. The shivering process in which the capillaries constrict or dilate in response to body temperature has matured. The skin becomes tough as the epidermis and dermis bond more tightly, protecting the child from fluid loss, infection, and irritation. The defense mechanisms of the skin and blood, particularly phagocytosis, are working more effectively than during infancy. The lymphatic tissues of the adenoids and tonsils enlarge during this period. Eruption of deciduous teeth continues. By 3 years of age, all 20 deciduous teeth are generally present (see Chapter 6). Toddlers’ emotions fluctuate greatly. They show ambivalence. They love one minute and hate the next. They cry, kick, and slap when they decide to play outdoors longer than the parent wants and then turn around and kiss that same parent for giving them a drink of water. It may be difficult for parents to understand these mood swings. Toddlers are usually trying to assert their independence. It may be best to ignore this behavior as long as children are not hurting themselves or someone else. After the tantrum, parents should divert toddlers to some pleasant activity. Table 7-2 summarizes behavior problems that may occur during early childhood, causes of those problems, and parenting tips for correcting the problems. Table 7-2 Modified from Schmitt, B. (2010). Discipline basics. ©2010 RelayHealth and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Toddlers need a certain amount of discipline. They get into many situations that are “over their head.” When adults make a firm decision for them, the problem is at least for the time being resolved. Children feel secure because parents have helped them escape from their own primitive natures. There is controversy concerning spanking children. A time-out period is effective (Figure 7-3). The general rule is 1 minute per year of the child’s age, up to 5 minutes. Time out can change almost any disruptive childhood behavior and is most effective if the child is older than 2 years of age. At about the end of the first year, the baby has begun vocalizing words such as “bye-bye,” “ma-ma,” and “da-da.” When toddlers see a happy response to these sounds, they repeat them. This is true throughout the toddler period. For small children to want to learn to talk, they must have an appreciative audience. At first, children refer to animals by the sounds the animals make. For example, before saying “dog,” toddlers repeat “bow-wow.” Soon they can say short phrases, such as “daddy gone car.” The 2-year-old can speak in simple two-word noun-verb sentences. Three-year-olds generally speak in three-word sentences, and so on. Toddlers respond also to tone of voice and facial expression. If an adult sounds threatening, toddlers may answer “no” and then “no” again in a louder voice. Toddlers also use “no” to express their developing autonomy. It is good to remember that toddlers who talk remarkably well and understand more than they say still cannot comprehend much of adult conversation. Sometimes when adults forget this, they scold the child merely for being too young to understand what is requested of them. Imagine yourself being punished in a foreign country because you are unable to speak or understand the language well enough to defend yourself. Adults who show empathy to small children can help minimize their frustrations. A guideline for vocalization appears in Table 7-1. Developmental norms in the use of language have been established. One widely used tool is the Denver II (see Appendix D), a revision of the Denver Developmental Screening Test (DDST). This test is used to assess the developmental status of children during their first 6 years. It evaluates according to four categories: personal-social, fine-motor–adaptive, language, and gross-motor. It is neither an intelligence test nor a neurologic test. A low score merely indicates a need for further evaluation. The test is designed for both professionals and paraprofessionals to use, and because it is a standardized test, proper administration and interpretation are crucial. Specific instructions for administering the test, scoring of the results, and a further description of the test are included in a manual that may be purchased from the publisher. In the summer months, children may sunburn quickly and should be protected by sunglasses that are 99% UV protection, and by clothing/sunscreen so as to prevent future skin damage. Sunscreen should be applied at least 30 minutes before going outside and be reapplied every 2 hours. Sunscreen should be used even on cloudy days. The SPF (sun protection factor) should be at least 15, and the UV protection should be “broad-spectrum” (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2010). Adapt the toddler’s environment accordingly. The chair and play table should be adjusted to their size (Figure 7-4). In some cases, this can be easily accomplished by placing a few magazines in the seat of the chair. A sturdy, small stool placed in the bathroom allows a toddler to stand at the proper height for brushing the teeth. These simple actions help to promote independence.

The Toddler

General Characteristics and Development

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

AGE

PHYSICAL

GROSS-MOTOR

FINE-MOTOR

VOCALIZATION

SOCIALIZATION

15 months

18 months

24 months

30 months

![]() Developmental Tasks

Developmental Tasks

![]() Physical Growth

Physical Growth

Guidance and Discipline

BEHAVIOR

CAUSES

PARENTING TIPS FOR CORRECTING BEHAVIOR

Biting

Teeth are established. Child wants attention; child is angry.

Establish “no biting” rule. Firmly tell child “no” while looking straight in the eye. Suggest alternative safe behavior. Put child in time out. Never bite your child for biting someone else.

Bedtime resistance or refusal

Child does not want to go to bed or stay in his or her bedroom; child has already established history of being allowed to sleep with parent.

A child should stay in his or her own bed at night; explain rules for this. Establish a pleasant bedtime routine. Escort child back to bed.

Physical fighting and spitting

Children fight when angry or jealous. They see other children or people on television act this way.

Establish “no hitting” rule because it does not solve problems. Teach children “Spitting doesn’t look nice.” Tell child to handle with words; ignore bullies. Use time out. Never hit your child for hitting someone else. Praise friendly behavior.

Nightmares

Relate to developmental challenges (toddlers fear separation from parents).

Reassure and cuddle child. Provide night light, leave door open. Talk about the dream during the day. Avoid frightening movies or television programs (applies more to older children).

Night terrors

These inherited disorders involve dreams during deep sleep from which it is difficult to awaken.

Sleep deprivation may contribute to these; have child take afternoon nap or at least “quiet time.” Comfort and reassure child during night terror.

Temper tantrums

Child is angry (may be precipitated by wanting something but not getting it).

Ignore child but monitor safety. Take child to his or her room for 2 to 5 min. Avoid spanking (conveys you are out of control).

Sibling quarrels

Occurs because of nature of being siblings. Quarrel over possessions, and so on. Want to gain parents’ attention.

Encourage them to settle their own arguments; if children come to you, keep an open mind when resolving and avoid getting in the middle. Intervene if argument gets too loud. Do not permit hitting. Avoid showing favoritism. Praise cooperative behavior.

Communication

Language Development

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Daily Care

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

inch longer than the big toe. The heels must fit securely. Children should wear their usual shoes at their periodic checkups because these show how the shoes have been worn, which indicates to the doctor how the children are using their bodies. Parents need to check the fit every few months because shoe size changes frequently as toddlers grow.

inch longer than the big toe. The heels must fit securely. Children should wear their usual shoes at their periodic checkups because these show how the shoes have been worn, which indicates to the doctor how the children are using their bodies. Parents need to check the fit every few months because shoe size changes frequently as toddlers grow.