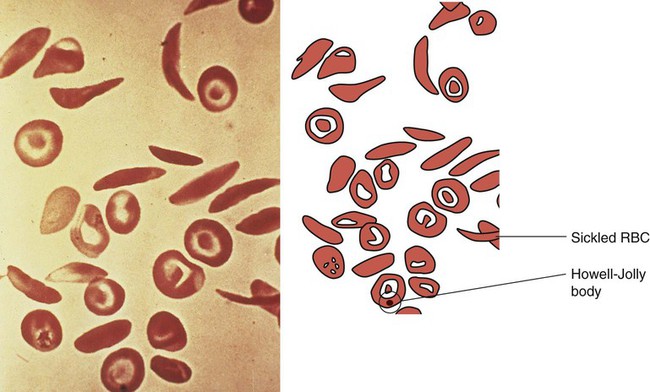

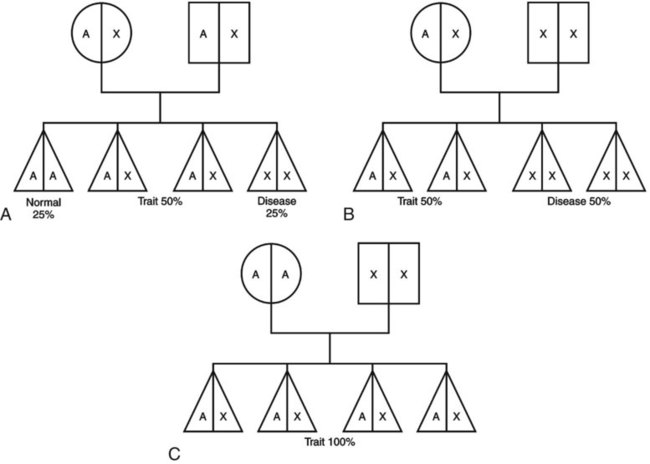

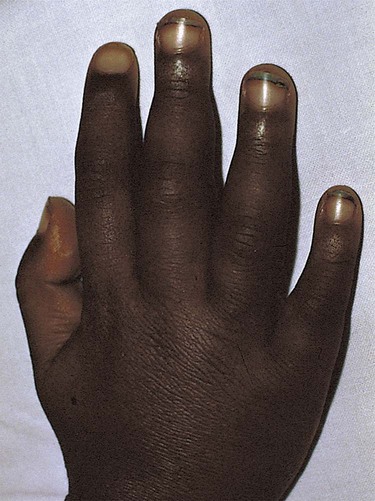

1. Define the vocabulary terms listed 2. Recommend four food sources of iron for an infant with iron-deficiency anemia 3. Discuss how sickle cell disease is inherited 4. Describe the care of hemarthrosis in a child with hemophilia 5. List four symptoms of acute lymphoid leukemia 6. Demonstrate comfort measures for a child undergoing chemotherapy 7. Discuss pre- and postoperative care of a child with Wilms tumor 8. Compare and contrast osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma Sickle cell anemia is one of a group of diseases in which normal Hgb (HgbA) is partly or completely replaced by abnormal sickle Hgb (HbS). Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited defect in the formation of hemoglobin. It occurs mainly in populations of African descent but is also carried by some people of Arabian, Greek, Maltese, and Sicilian descent or other Mediterranean groups. Sickling caused by decreases in blood oxygen may be triggered by dehydration, infection, physical or emotional stress, or exposure to cold. Laboratory examination of the affected child’s blood shows that the red blood cell has changed its shape to resemble that of a sickle blade, from which the name of the disorder is derived (Figure 21-1). These cells contain an abnormal form of hemoglobin, termed hemoglobin S (the sickling type). The membranes of these cells are fragile and easily destroyed. Their crescent shape makes it difficult for them to pass through the capillaries, causing a pile-up of cells in the small vessels. This clumping together may lead to a thrombosis (clot) and cause an obstruction. Infarcts, or areas of dead tissue, may result when the tissue is denied proper blood supply. These generally develop in the spleen but may also be seen in other areas of the body, such as the brain, heart, lungs, GI tract, kidneys, and bones. The child feels pain in the affected area. This severe form of the disease results when the child inherits the abnormal gene from each parent (Figure 21-2). Each offspring has one chance in four of inheriting the disease (not one of four children). The incidence rate is about 1 in 600 African Americans. The symptoms generally do not appear until the last part of the first year of life, although they may occur as early as 4 months (fetal hemoglobin inhibits sickling). The first symptom may be an unusual swelling of the fingers and toes called hand-foot syndrome or dactylitis (Figure 21-3). Damage to the kidney can result, affecting the kidney’s ability to concentrate urine. This can lead to increased urination in children. Small children with SCD are difficult to toilet-train and may wet the bed for several years. When this is explained to parents as a side effect of the disease, they may be more able to accept the problem. Teenagers and adults with SCD may develop painful, slow-healing ulcers on the lower legs, particularly on the ankles. Chronic anemia is present, which is why the disease may be referred to as sickle cell anemia. The hemoglobin level ranges from 6 to 9 g/dL or lower. The child is pale, tires easily, and loses appetite. These manifestations of anemia are complicated by what is termed the sickle cell crisis, which can be fatal. A number of types of crises have been defined. They differ in pathology and may require somewhat different treatment (Table 21-1). Unfortunately, in some cases, the sickle cell crisis is the first evidence of the condition. For this reason, all 50 states screen all newborn infants. Parents are contacted immediately if there is a positive state screening result. Regularly scheduled health visits, penicillin prophylaxis, and immunizations including influenza, pneumococcal, and meningococcal vaccine should be stressed with the parents. Table 21-1 Summary of Types of Sickle Cell Events In a sickle cell crisis, the child appears acutely ill with severe abdominal pain. Muscle spasms, leg pains, or painful swollen joints may be seen. Fever, vomiting, hematuria, convulsions, stiff neck, coma, or paralysis can result, depending on the organs involved. The child may be jaundiced. Cardiac enlargement and murmurs are not uncommon. Priapism is a painful penile erection that occurs in male children, adolescents, and adults. This can be a medical emergency if it is prolonged. According to Pack-Mabien and Haynes (2009), cholelithiasis (formation of gallstones) and retinopathy (disorder of the retina) resulting in blindness are additional complications to monitor for in children with sickle cell disease. The sickle cell crises recur periodically throughout childhood; however, they tend to decrease with age. Between episodes, children should be kept in good health. They should refrain from becoming overly tired. They also should avoid situations such as flying in an unpressurized airplane or exercising at high altitude because oxygen concentrations are already reduced in the blood. Added stress and exposure to cold may lower resistance, causing additional problems. Overheating, which can lead to dehydration, should also be avoided. An injured knee, elbow, or ankle presents particular problems because of hemorrhage into the joint cavity (hemarthrosis) and is a cardinal sign in children with hemophilia. The earliest joint hemorrhages appear most commonly in the ankle, from instability of this joint as the toddler assumes an upright posture. Many children with severe hemophilia develop a “target” joint where repetitive bleeding episodes occur (Kliegman et al., 2007). The affected joint is stiff, warm, red, and swollen. Joint limitation occurs. Repeated hemorrhages may cause permanent deformities that could disable the child.

Hematology and Oncology Disorders

Sickle Cell Anemia

Sickle Cell Disease

TYPE

CHARACTERISTICS

SYMPTOMS

Vaso-occlusive crisis

Most common; not life threatening; obstruction of circulation; resulting in ischemia, necrosis, and infarctions

Pain, fever, dactylitis, bone and joint pain, abdominal pain, cardiovascular accident, priapism

Acute chest syndrome

Pulmonary infarcts

Chest pain, cough, fever, hypoxia, tachypnea

Dactylitis (hand-foot syndrome)

Infarction of short tubular bones, self-limiting, occurs in children 6 months to 4 years of age

Localized swelling of hands and feet

Acute splenic sequestration

Acute, episodic, even when, for unknown reasons, blood pools in the spleen, which can result in life-threatening circulatory collapse and death; commonly preceded by acute febrile illness

Enlarged spleen, pallor, irritability, weakness, dyspnea, tachycardia, hypotension

Aplastic episodes

Diminished production of red blood cells, usually caused by viral or bacterial infection

Pallor, lethargy, faintness, anemia

Hemophilia

Signs and Symptoms

Hematology and Oncology Disorders

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access