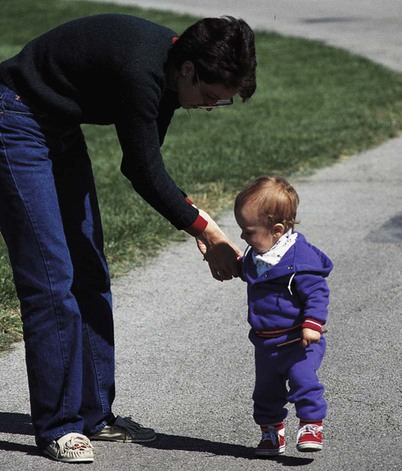

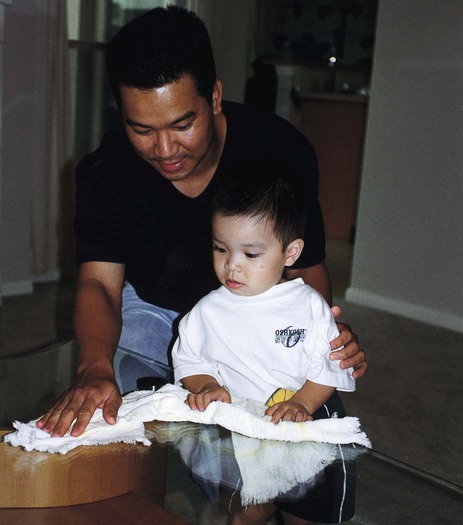

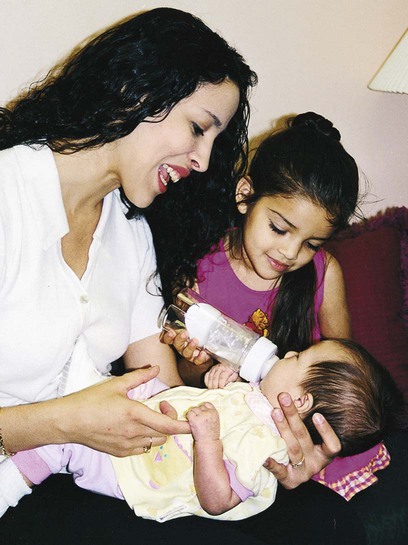

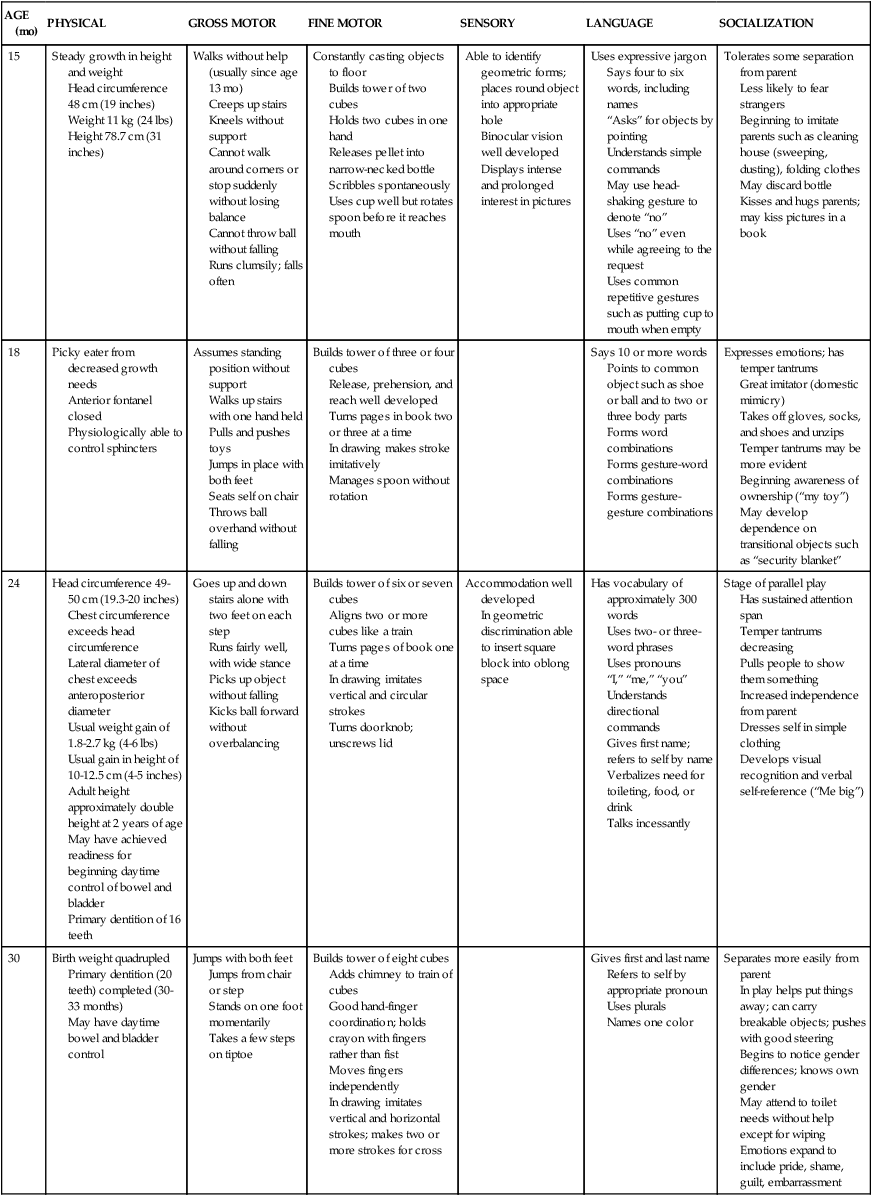

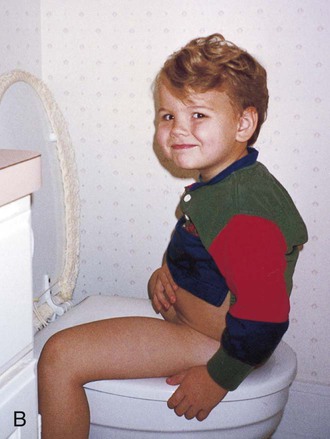

Chapter 32 On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Identify the major biologic, psychosocial, cognitive, and social developments during the toddler years. • Relate separation anxiety and negativism to developmental tasks. • Recognize readiness for toilet training and offer parents guidelines. • Prepare parents of toddlers for the birth of a sibling. • Provide parents with guidelines for handling temper tantrums. • Provide parents with feeding recommendations for the toddler. • Outline a preventive dental hygiene plan for toddlers. • Provide anticipatory guidance to parents regarding injury prevention based on the toddler’s developmental achievements. Most of the physiologic systems are relatively mature by the end of toddlerhood. Volume of the respiratory tract and growth of associated structures continue to increase during early childhood, lessening some of the factors that predisposed the child to frequent and serious infections during infancy. The internal structures of the ear and throat continue to be short and straight, and the lymphoid tissue of the tonsils and adenoids continues to be large. As a result otitis media, tonsillitis, and upper respiratory tract infections are common. The respiratory and heart rates slow, and the blood pressure increases (see Appendix C). Respirations continue to be abdominal. The major gross motor skill during the toddler years is the development of locomotion. By 12 to 13 months of age toddlers walk alone using a wide stance for extra balance, and by 18 months they try to run but fall easily (Fig. 32-1). Between 2 and 3 years of age refinement of the upright, biped position is evident in improved coordination and equilibrium. At age 2 years toddlers can walk up and down stairs; by age 2½ years they can jump using both feet, stand on one foot for a second or two, and manage a few steps on tiptoe. By the end of the second year they can stand on one foot, walk on tiptoe, and climb stairs with alternate footing. • Differentiation of self from others, particularly the mother. • Toleration of separation from parent. • Ability to delay gratification. • Control over bodily functions. • Acquisition of socially acceptable behavior. • Verbal means of communication. • Ability to interact with others in a less egocentric manner. Mastery of these goals is only begun during late infancy and the toddler years, and tasks such as developing interpersonal relationships with others may not be completed until adolescence. However, crucial foundations for successful completion of such developmental tasks are established during these early formative years. According to Erikson (1963), the developmental task of toddlerhood is acquiring a sense of autonomy while overcoming a sense of doubt and shame. As infants gain trust in the predictability and reliability of their parents, environment, and interaction with others, they begin to discover that their behavior is their own and that it has a predictable, reliable effect on others. However, although they realize their will and control over others, they are confronted with the conflict of exerting autonomy and relinquishing the much-enjoyed dependence on others. Exerting their will has definite negative consequences, whereas retaining dependent, submissive behavior is generally rewarded with affection and approval. At the same time continued dependency creates a sense of doubt regarding their potential capacity to control their actions. This doubt is compounded by a sense of shame for feeling this urge to revolt against others’ will and a fear that they will exceed their own capacity for manipulating the environment. Several characteristics, especially negativism and ritualism, are typical of toddlers in their quest for autonomy. As they attempt to express their will, they often act with negativism, the persistent negative response to requests. The words “no” or “me do” can be the sole vocabulary. Emotions are expressed strongly, usually in rapid mood swings. One minute toddlers can be engrossed in an activity, and the next minute they might be extremely frustrated because they are unable to manipulate a toy or open a door. If scolded for doing something wrong, they can have a temper tantrum and almost instantaneously pull at the parent’s legs to be picked up and comforted. Understanding and coping with these swift changes in behavior is often difficult for parents. Many find the negativism exasperating and, instead of dealing constructively with it, give in to it, which further threatens children in their search for learning acceptable methods of interacting with others (see Temper Tantrums, p. 932; see Negativism, p. 933). In contrast to negativism, which often disrupts the environment, ritualism, the need to maintain sameness and reliability, provides a sense of comfort. Toddlers can venture out with security when they know that familiar people, places, and routines still exist. One can easily understand why change such as hospitalization represents such a threat to these children. Without the comfortable rituals there is little opportunity to exert autonomy. Consequently dependency and regression occur (see Regression, p. 933). Imitation displays deeper meaning and understanding. There is greater symbolization to imitation. The child is acutely aware of others’ actions and attempts to copy them in gestures and words. Domestic mimicry (imitating household activities) and gender-role behavior become increasingly common during this stage, especially during the second year. Identification with the parent of the same gender becomes apparent by the second year and represents the child’s intellectual ability to identify different models of behavior and imitate them appropriately (Fig. 32-2). At approximately 2 years of age the child enters the preconceptual phase of cognitive development, which lasts until about age 4 years. The preconceptual phase is a subdivision of the preoperational phase, which spans ages 2 to 7 years. It is primarily one of transition that bridges the purely self-satisfying behavior of infancy and the rudimentary socialized behavior of latency. Preoperational thought implies that children cannot think in terms of operations (i.e., the ability to manipulate objects in relation to one another in a logical fashion). Rather toddlers think primarily on the basis of their perception of an event. Problem solving is based on what they see or hear directly rather than on what they recall about objects and events. Several characteristics are unique to preoperational thought (Box 32-1). Spiritual development in children is often discussed in terms of the child’s developmental level because the evolution of spirituality often parallels cognitive development (Elkins and Cavendish, 2004). The child’s family and environment strongly influence his or her perception of the world around him or her, and this often includes spirituality. Furthermore, family values, beliefs, customs, and expressions of these influence the child’s perception of his or her spiritual self (Elkins and Cavendish, 2004). Neuman (2011) proposes that Fowler’s stages of faith (Fowler, 1981) be used to better understand children and spirituality; she provides an excellent overview of the stages of faith in childhood. The relationship among spirituality, illness in childhood, and nursing has been studied in the context of suffering, terminal illness such as cancer, and end-of-life care. In the past decade there has been an increased interest in and focus on spiritual care in adults and children as further understanding of the influence of one’s spirituality on health, illness, and well-being has progressed. Toddlers learn about God through the words and actions of those closest to them. They have only a vague idea of God and religious teachings because of their immature cognitive processes; however, if God is spoken about with reverence, young children associate God with something special. During this period the assignment of powerful religious symbols and images is strongly influenced by the manner in which it is presented; therein lies the potential for the development of guilt and fear or conversely love and companionship with religious symbols (Roehlkepartain, King, Wagener, et al., 2006). Toddlers are said to be in the intuitive-projective phase of Fowler’s faith construct (Fowler, 1981) wherein thinking is largely based on fantasy and rather fluid in relation to reality and fantasy. God may be described as being around like air by the toddler because of the fluidity in dividing fantasy and reality (Neuman, 2011). Toddlers begin to assimilate behaviors associated with the divine (folding hands in prayer). Routines such as saying prayers before meals or at bedtime can be important and comforting. Because toddlers tend to find solace in ritualistic behavior and routines, they incorporate routines associated with religious practices into their behavioral patterns without understanding all of the implications of the rituals until later. Near the end of toddlerhood, when children use preoperational thought, there is some advancement of their understanding of God. Religious teachings such as reward or fear of punishment (heaven or hell) and moral development (see Chapter 28), may influence their behavior (Fosarelli, 2003). Children in this age-group are learning vocabulary associated with anatomy, elimination, and reproduction. Certain associations between words and functions become significant and can influence future sexual attitudes. For example, if parents refer to the genitalia as dirty, especially in the context of elimination, this association between “genitalia” and “dirty” may be transferred to sexual functions later in life. Sex-role differences become obvious to children and are evident in much of toddlers’ imitative play. Although current research indicates that prenatal exposure to testosterone strongly influences the individual’s gender identity, researchers also indicate that there are sensitive periods (e.g., puberty) that may influence the development of gender identity (Berenbaum and Beltz, 2011; Hines, 2011; Savic, Garcia-Falqueras, and Swaab, 2010). A sense of maleness or femaleness, or gender identity, is formed by age 3 years, and the child’s feelings about being male or female begin to form (Fonseca and Greydanus, 2007). Early attitudes are formed about affectionate behaviors between adults from observing parental and other adult sexual or sensual activities. (See also Sex Education, Chapter 33.) The quality of relationships with parents is important to the child’s capacity for sexual and emotional relationships later in life. According to Harpaz-Rotem and Bergman (2006), the separation-individuation phase encompasses the phenomenon of rapprochement; as the toddler separates from the mother and begins to make sense of experiences in the environment, he or she is drawn back to the mother for assistance in verbally articulating the meaning of the experiences. Developmentally the term rapprochement means the child moves away and returns for reassurance. If the mother’s response to the toddler is inappropriate, the toddler may experience insecurity and confusion. Transitional objects such as a favorite blanket or toy provide security for children, especially when they are separated from parents, dealing with a new stress, or just fatigued (Fig. 32-3). Security objects often become so important to toddlers that they refuse to have them taken away. Such behavior is normal; there is no need to discourage this tendency. During separations such as day care, hospitalization, or even overnight stays with relatives, transitional objects should be provided to minimize any feelings of fear or loneliness. At age 1 year children use one-word sentences or holophrases. The word “up” can mean “pick me up” or “look up there.” For children the one word conveys the meaning of a sentence, but to others it may mean many things or nothing. At this age about 25% of the vocalizations are intelligible. By the age of 2 years children use multiword sentences by stringing together two or three words such as the phrases “mama go bye-bye” or “all gone,” and approximately 65% of their speech is understandable. By 3 years the children put words together into simple sentences, begin to master grammatical rules, acquire five or six new words daily, know their age and gender, and can count three objects correctly. Looking at books during this period provides an ideal setting for further language development (Feigelman, 2011). Authorities have evaluated the impact of television viewing on toddler language development and found that those who started watching television at younger than 12 months of age and who watched longer than 2 hours per day had significant language delays (Chonchaiva and Pruksananonda, 2008). Adult-child conversations with infants and toddlers have been shown to positively affect language development; the researchers recommend reading, storytelling, and interactive adult-child communication (Zimmerman, Gilkerson, Richards, et al., 2009). The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Council on Communications and Media (2011) reaffirms that televised or recorded media usage in children younger than 2 years of age decreases language skills and the time parents interact with the child. Furthermore, educational programs have not been shown to increase cognitive skills in young children (AAP Council on Communications and Media, 2011). Gestures precede or accompany each of the language milestones up to 30 months of age (putting phone to ear, pointing). After sufficient language development, gestures phase out, and the pace of word learning increases (Bates and Dick, 2002). Play magnifies toddlers’ physical and psychosocial development. Interaction with people becomes increasingly important. The solitary play of infancy progresses to parallel play (i.e., toddler play alongside, not with, other children). Although sensorimotor play is still prominent, there is much less emphasis on the exclusive use of one sensory modality. Toddlers inspect toys, talk to toys, test toys’ strength and durability, and invent several uses for toys. Imitation is one of the most distinguishing characteristics of play and enriches children’s opportunity to engage in fantasy. With less emphasis on gender-stereotyped toys, play objects such as dolls, carriages, dollhouses, balls, dishes, cooking utensils, child-size furniture, trucks, and dress-up clothes are suitable for both genders (Fig. 32-4); however, boys may be more interested than girls in activities related to trucks, trailers, action figures, and building blocks, and girls may prefer doll-related activities. Increased locomotive skills make push-pull toys, straddle trucks or cycles, a small gym and slide, balls of various sizes, and riding toys appropriate for energetic toddlers. Finger paints; thick crayons; chalk; blackboard; paper; and puzzles with large, simple pieces use toddlers’ developing fine motor skills. Interlocking blocks in various sizes and shapes provide hours of fun and during later years are useful objects for creative and imaginative play. The most educational toy is the one that fosters the interaction of an adult with a child in supportive, unconditional play. Toys should not be substitutes for the attention of devoted caregivers, but they can enhance these interactions (Glassy, Romano, and AAP Committee on Early Childhood, 2003). Parents and other providers are encouraged to allow children to play with a variety of simple toys that foster creative thinking (e.g., blocks, dolls, and clay) rather than passive toys that the child observes (battery-operated or mechanical). Active play time should also be encouraged over the use of computer or video games, which are more passive (Ginsburg and AAP Committee on Communications, 2007). Certain aspects of play are related to emerging linguistic abilities. Talking is a form of play for toddlers, who enjoy musical toys such as age-appropriate compact disk (CD) players, “talking” dolls and animals, and toy telephones. Children’s television programs are appropriate for some children over 2 years of age who learn to associate words with visual images. However, total media time should be limited to 1 hour or less of quality programming per day. Parents are encouraged to allow the child to engage in unstructured playtime, which is considered much more beneficial than any electronic media exposure (AAP Council on Communications and Media, 2011). Toddlers also enjoy “reading” stories from a picture book and imitating the sounds of animals. Selection of appropriate toys must involve safety factors, especially in relation to size and sturdiness. The oral activity of toddlers puts them at risk for aspirating small objects and ingesting toxic substances. Parents need to be especially vigilant of toys played with in other children’s homes and those of older siblings. Toys are a potential source of serious bodily damage to toddlers, who may have the physical strength to manipulate them but not the knowledge to appreciate their danger (Stephenson, 2005). Government agencies do not inspect and police all toys on the market. Therefore adults who purchase play equipment, supervise purchases, or allow children to use play equipment need to evaluate its safety, including toys that are gifts or those that are purchased by the children themselves. Adults should also be alert to notices of toys determined to be defective and recalled by the manufacturers. Parents and health care workers can obtain information on a variety of recalled products and report potentially dangerous toys and child products to the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission* or, in Canada, the Canadian Toy Testing Council.† Printable tips on toy safety are also available from Safe Kids Worldwide (www.safekids.org). Table 32-1 summarizes the major features of growth and development for the age-groups of 15, 18, 24, and 30 months. TABLE 32-1 GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT DURING TODDLER YEARS Voluntary control of the anal and urethral sphincters is achieved sometime after the child is walking, probably between ages 18 and 24 months. However, complex psychophysiologic factors are required for readiness. The child must be able to recognize the urge to let go and hold on and communicate this sensation to the parent. In addition, some motivation is probably involved in the desire to please the parent by holding on rather than pleasing oneself by letting go. Cultural beliefs may also affect the age at which children demonstrate readiness (Feigelman, 2011). Schmitt (2004) notes that comparative studies over the past 5 decades indicate that children in the 1990s in the United States were toilet trained at a later age (18 months in the 1960s versus 36 months in the 1990s); one possible contributing factor is the availability and convenience of disposable diapers. Another study found that the child’s average age at initiation of toilet training was 20.6 months (Horn, Brenner, Rao, et al., 2006). Five markers signal a child’s readiness to toilet train: bladder readiness, bowel readiness, cognitive readiness, motor readiness, and psychologic readiness (Schmitt, 2004). According to some experts, physiologic and psychologic readiness is not complete until ages 22 to 30 months (Schum, Kolb, McAuliffe, et al., 2002); however, Schmitt (2004) emphasizes that parents should begin preparing their children for toilet training earlier than 30 months. By this time children have mastered most essential gross motor skills, can communicate intelligibly, are in less conflict with their parents in terms of self-assertion and negativism, and are aware of the ability to control the body and please their parents. Both the AAP and the Canadian Paediatric Society recommend starting toilet training by 18 months of age and suggest that the child must be interested in the process (Kiddoo, 2012). There is no universal right age to begin toilet training or an absolute deadline to complete it. An important role for the nurse is to help parents identify the readiness signs in their children (see Guidelines box).* On average girls are developmentally ready to begin toilet training 2 to 2½ months before boys (Schum, Kolb, McAuliffe, et al., 2002). Nighttime bladder control normally takes several months to years after daytime training begins. This is because the sleep cycle needs to mature so the child can awake in time to urinate. Feigelman (2011) indicates that bed-wetting is normal in girls up to age 4 years and boys up to age 5 years. Few children have night-wetting episodes after daytime dryness is totally achieved; however, children who do not have nighttime dryness by the age of 6 years are likely to require intervention (Mercer, 2003). A number of techniques are helpful when initiating training, and cultural differences should be considered. In the United States some of the options recommended by practitioners include the Brazelton child-oriented approach, the AAP guidelines (which are similar to Brazelton method), Dr. Spock’s training method, and the intensive “toilet-training-in-a-day” (operant conditioning) approach by Azrin and Foxx (Choby and George, 2008). An extensive study and review by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in 2006 (Klassen, Kiddoo, Lang, et al., 2006) concluded that the child-oriented method and the Azrin and Foxx method were effective at toilet training healthy children (Choby and George, 2008). Another method emerging in the literature involves early assisted toilet training of infants around 2 to 3 weeks of age, but there are no studies assessing this method (Kiddoo, 2012). The following discussion of toilet training methods includes suggestions from the child-oriented approach. Parents should begin the readiness phase of toilet training by teaching the child about how the body functions in relation to voiding and having a stool. Schmitt (2004) suggests that parents talk about how adults and animals perform such functions on a routine basis. Another suggestion is to make toilet training as easy and simple as possible. Important considerations are the selection of the child’s clothing and the potty chair or use of the toilet. A freestanding potty chair allows children a feeling of security (Fig. 32-5, A). Planting the feet firmly on the floor also facilitates defecation. Another option is a portable seat attached to the regular toilet, which may ease the transition from potty chair to regular toilet. Placing a small bench under the feet helps stabilize the child’s position. It is probably best to keep the potty in the bathroom and let the child observe the excreta being flushed down the toilet to associate these activities with usual practices. If a potty chair is not available, having the child sit facing the toilet tank provides added support (Fig. 32-5, B). Practice sessions should be limited to 5 to 8 minutes; a parent should stay with the child, practicing sanitary habits after every session. Children should be praised for cooperative behavior and successful evacuation. Dressing children in easily removed clothing; using training pants, “pull-on” diapers, or underwear; and encouraging imitation by watching others are other helpful suggestions. Pregnancy is an abstraction for toddlers. They need concrete illustrations of how the baby is growing inside the mother. It is an excellent opportunity for introducing aspects of reproduction and sexuality. Seeing simple pictures of the uterus and fetus and feeling the fetus move help the child feel involved in the experience (see Fig. 8-3). Children also benefit from classes for siblings that may be part of prenatal sessions (see Fig. 8-4). When the newborn arrives, toddlers keenly feel the changed focus of attention. Visitors may initiate problems when they inadvertently shower the infant with attention and presents while neglecting the older child. Parents can minimize this by alerting visitors to the toddler’s needs and including the child in the visits as much as possible. The toddler can also help with the care of the newborn by getting diapers and doing other small tasks (Fig. 32-6).

The Toddler and Family

Promoting Optimal Growth and Development

Biologic Development

Proportional Changes

Maturation of Systems

Gross and Fine Motor Development

Psychosocial Development

Developing a Sense of Autonomy (Erikson)

Cognitive Development

Sensorimotor and Preoperational Phase (Piaget)

Invention of New Means Through Mental Combinations

Preoperational Phase

Spiritual Development

Development of Gender Identity

Social Development

Language

Play

AGE (mo)

PHYSICAL

GROSS MOTOR

FINE MOTOR

SENSORY

LANGUAGE

SOCIALIZATION

15

Steady growth in height and weight

Head circumference 48 cm (19 inches)

Weight 11 kg (24 lbs)

Height 78.7 cm (31 inches)

Walks without help (usually since age 13 mo)

Creeps up stairs

Kneels without support

Cannot walk around corners or stop suddenly without losing balance

Cannot throw ball without falling

Runs clumsily; falls often

Constantly casting objects to floor

Builds tower of two cubes

Holds two cubes in one hand

Releases pellet into narrow-necked bottle

Scribbles spontaneously

Uses cup well but rotates spoon before it reaches mouth

Able to identify geometric forms; places round object into appropriate hole

Binocular vision well developed

Displays intense and prolonged interest in pictures

Uses expressive jargon

Says four to six words, including names

“Asks” for objects by pointing

Understands simple commands

May use head-shaking gesture to denote “no”

Uses “no” even while agreeing to the request

Uses common repetitive gestures such as putting cup to mouth when empty

Tolerates some separation from parent

Less likely to fear strangers

Beginning to imitate parents such as cleaning house (sweeping, dusting), folding clothes

May discard bottle

Kisses and hugs parents; may kiss pictures in a book

18

Picky eater from decreased growth needs

Anterior fontanel closed

Physiologically able to control sphincters

Assumes standing position without support

Walks up stairs with one hand held

Pulls and pushes toys

Jumps in place with both feet

Seats self on chair

Throws ball overhand without falling

Builds tower of three or four cubes

Release, prehension, and reach well developed

Turns pages in book two or three at a time

In drawing makes stroke imitatively

Manages spoon without rotation

Says 10 or more words

Points to common object such as shoe or ball and to two or three body parts

Forms word combinations

Forms gesture-word combinations

Forms gesture-gesture combinations

Expresses emotions; has temper tantrums

Great imitator (domestic mimicry)

Takes off gloves, socks, and shoes and unzips

Temper tantrums may be more evident

Beginning awareness of ownership (“my toy”)

May develop dependence on transitional objects such as “security blanket”

24

Head circumference 49-50 cm (19.3-20 inches)

Chest circumference exceeds head circumference

Lateral diameter of chest exceeds anteroposterior diameter

Usual weight gain of 1.8-2.7 kg (4-6 lbs)

Usual gain in height of 10-12.5 cm (4-5 inches)

Adult height approximately double height at 2 years of age

May have achieved readiness for beginning daytime control of bowel and bladder

Primary dentition of 16 teeth

Goes up and down stairs alone with two feet on each step

Runs fairly well, with wide stance

Picks up object without falling

Kicks ball forward without overbalancing

Builds tower of six or seven cubes

Aligns two or more cubes like a train

Turns pages of book one at a time

In drawing imitates vertical and circular strokes

Turns doorknob; unscrews lid

Accommodation well developed

In geometric discrimination able to insert square block into oblong space

Has vocabulary of approximately 300 words

Uses two- or three-word phrases

Uses pronouns “I,” “me,” “you”

Understands directional commands

Gives first name; refers to self by name

Verbalizes need for toileting, food, or drink

Talks incessantly

Stage of parallel play

Has sustained attention span

Temper tantrums decreasing

Pulls people to show them something

Increased independence from parent

Dresses self in simple clothing

Develops visual recognition and verbal self-reference (“Me big”)

30

Birth weight quadrupled

Primary dentition (20 teeth) completed (30-33 months)

May have daytime bowel and bladder control

Jumps with both feet

Jumps from chair or step

Stands on one foot momentarily

Takes a few steps on tiptoe

Builds tower of eight cubes

Adds chimney to train of cubes

Good hand-finger coordination; holds crayon with fingers rather than fist

Moves fingers independently

In drawing imitates vertical and horizontal strokes; makes two or more strokes for cross

Gives first and last name

Refers to self by appropriate pronoun

Uses plurals

Names one color

Separates more easily from parent

In play helps put things away; can carry breakable objects; pushes with good steering

Begins to notice gender differences; knows own gender

May attend to toilet needs without help except for wiping

Emotions expand to include pride, shame, guilt, embarrassment

Coping with Concerns Related to Normal Growth and Development

Toilet Training

Sibling Rivalry

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Toddler and Family

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access