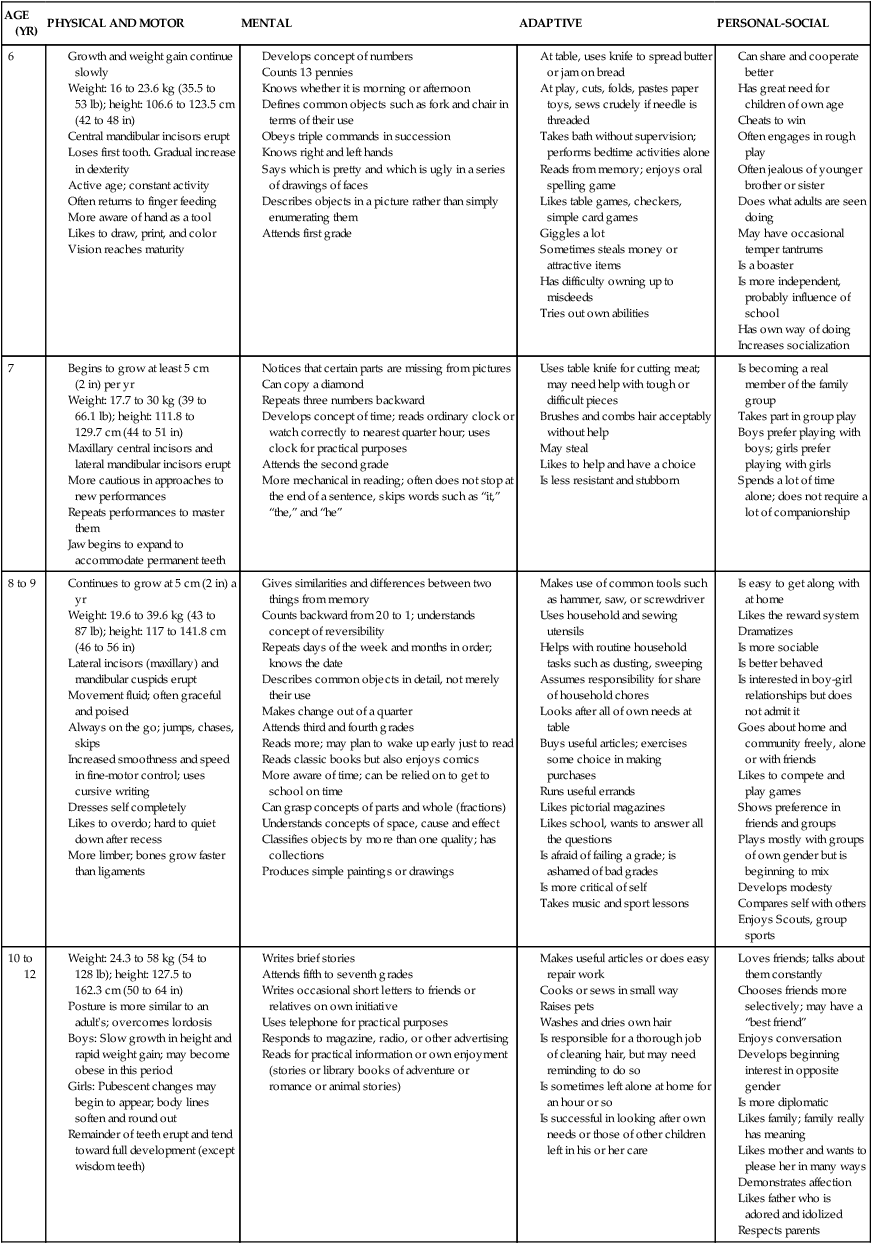

1. Define the vocabulary terms listed 2. Describe the physical and psychosocial development of children from 6 to 12 years of age, listing, where appropriate, age-specific events and types of guidance 3. Discuss how to assist parents in preparing a child for school entry 4. List two ways in which school life influences the growing child 5. Identify the positive and negative aspects of television viewing and playing video games 6. Discuss safety issues related to the school-age child 7. Plan a diet that provides adequate nutrition for the school-age child Growth is slow until the spurt, which occurs directly before puberty. Weight gains are more rapid than increases in height. The average gain in weight per year is about The shape of the eye also changes with growth. 20/40 vision is achieved by 3 years of age, 20/30 vision by 4 years of age, and 20/30 by 5 to 6 years of age. Visual acuity can be measured by The vital signs of the school-age child are similar to those of the adult. Temperature is 98.6° F (37° C), pulse is 60 to 95 beats per minute, and the respiratory rate is 14 to 22 breaths per minute. The systolic blood pressure ranges from 100 to 120 mm Hg, and the diastolic blood pressure ranges from 60 to 75 mm Hg. (See Chapter 3 for further discussion on vital signs.) Boys are slightly taller and somewhat heavier than girls until changes indicating puberty appear. The differences among children are greater at the end of middle childhood than at the beginning. According to Erikson’s theories of psychosocial development, the school-age child is in the stage of industry versus inferiority. The child is a worker and producer and wants to accomplish tasks. Competitiveness is common (Figure 9-1). The school-age child’s social world is continually expanding, and he or she achieves new competencies. However, without success in this area, they feel inferior. Parents and teachers need to support children in achieving success and developing self-esteem. Table 9-1 summarizes growth and development for the various school-age groups. Table 9-1 Growth and Development During School-Age Years From Hockenberry, M.J., and Wilson, D. (2007). Wong’s nursing care of infants and children (8th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby. Active play is still important to both genders (Figure 9-2). The boys are more apt to tease the girls than to participate in such games as jump rope or tag. Both genders enjoy bike riding and table games. Realistic toys, such as dolls that can be bathed and fed or trains that back up and whistle, appeal to the 7-year-old. Comic books are also popular (Figure 9-3). Becoming increasingly independent, these children imagine themselves accomplishing feats more adventurous than those of their parents. Competitive sports, reading, listening to music, and watching television and movies are popular. Contact sports should be limited to minimize permanent growth-related injuries (Figure 9-4). The child begins to develop interests such as music and may desire to take lessons. Children know the date, can repeat months of the year in order, can multiply, and do simple division. They take care of their bodily needs, and by now table manners have considerably improved. Groups of friends are still important (Figure 9-5). They are not ready to stand alone, but they cannot bear the thought of depending on their parents. They insist that they must overcome their problems without parental help. Their attitude implies, “Can’t you see that I’m not a child anymore?”

The School-Age Child

General Characteristics and Development

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

![]() Physical Growth

Physical Growth

to 7 pounds (2.5 to 3.2 kg). The average yearly increase in height is approximately 2 inches (5.5 cm). Head circumference increases only 2 to 3 cm throughout this entire period. This reflects slowed brain growth with complete brain growth occurring at 10 years of age. Myelinization, the growth process of the myelin sheath around the nerve fiber, is complete by 7 years of age and results in the refinement of fine-motor coordination (Kleigman et al., 2007).

to 7 pounds (2.5 to 3.2 kg). The average yearly increase in height is approximately 2 inches (5.5 cm). Head circumference increases only 2 to 3 cm throughout this entire period. This reflects slowed brain growth with complete brain growth occurring at 10 years of age. Myelinization, the growth process of the myelin sheath around the nerve fiber, is complete by 7 years of age and results in the refinement of fine-motor coordination (Kleigman et al., 2007).

to 3 years of age (Kleigman et al., 2007). The capabilities of the child’s sense organs, including hearing, have an important bearing on learning abilities.

to 3 years of age (Kleigman et al., 2007). The capabilities of the child’s sense organs, including hearing, have an important bearing on learning abilities.

Developmental Theories

Biological and Psychosocial Development

The 7-Year-Old

The 9-Year-Old

The 11- to 12-Year-Old

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The School-Age Child

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access